Geological Structures and Maps a PRACTICAL GUIDE This�Page�Intentionally�Left�Blank Geological Structures and Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean

Tectonic Imbrication and Foredeep Development in the Penokean Orogen, East-Central Minnesota An Interpretation Based on Regional Geophysics and the Results of Test-Drilling The Penokean Orogeny in Minnesota and Upper Michigan A Comparison of Structural Geology U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1904-C, D AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. -

Strike and Dip Refer to the Orientation Or Attitude of a Geologic Feature. The

Name__________________________________ 89.325 – Geology for Engineers Faults, Folds, Outcrop Patterns and Geologic Maps I. Properties of Earth Materials When rocks are subjected to differential stress the resulting build-up in strain can cause deformation. Depending on the material properties the result can either be elastic deformation which can ultimately lead to the breaking of the rock material (faults) or ductile deformation which can lead to the development of folds. In this exercise we will look at the various types of deformation and how geologists use geologic maps to understand this deformation. II. Strike and Dip Strike and dip refer to the orientation or attitude of a geologic feature. The strike line of a bed, fault, or other planar feature, is a line representing the intersection of that feature with a horizontal plane. On a geologic map, this is represented with a short straight line segment oriented parallel to the strike line. Strike (or strike angle) can be given as either a quadrant compass bearing of the strike line (N25°E for example) or in terms of east or west of true north or south, a single three digit number representing the azimuth, where the lower number is usually given (where the example of N25°E would simply be 025), or the azimuth number followed by the degree sign (example of N25°E would be 025°). The dip gives the steepest angle of descent of a tilted bed or feature relative to a horizontal plane, and is given by the number (0°-90°) as well as a letter (N, S, E, W) with rough direction in which the bed is dipping. -

Introduction San Andreas Fault: an Overview

Introduction This volume is a general geology field guide to the San Andreas Fault in the San Francisco Bay Area. The first section provides a brief overview of the San Andreas Fault in context to regional California geology, the Bay Area, and earthquake history with emphasis of the section of the fault that ruptured in the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. This first section also contains information useful for discussion and making field observations associated with fault- related landforms, landslides and mass-wasting features, and the plant ecology in the study region. The second section contains field trips and recommended hikes on public lands in the Santa Cruz Mountains, along the San Mateo Coast, and at Point Reyes National Seashore. These trips provide access to the San Andreas Fault and associated faults, and to significant rock exposures and landforms in the vicinity. Note that more stops are provided in each of the sections than might be possible to visit in a day. The extra material is intended to provide optional choices to visit in a region with a wealth of natural resources, and to support discussions and provide information about additional field exploration in the Santa Cruz Mountains region. An early version of the guidebook was used in conjunction with the Pacific SEPM 2004 Fall Field Trip. Selected references provide a more technical and exhaustive overview of the fault system and geology in this field area; for instance, see USGS Professional Paper 1550-E (Wells, 2004). San Andreas Fault: An Overview The catastrophe caused by the 1906 earthquake in the San Francisco region started the study of earthquakes and California geology in earnest. -

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map

Lesson 4–How to Read a Topographic Map Key teaching points Suggestions for teaching Ask students to answer these ques- this lesson (3, 35-minute sessions) tions and fill in their answers on A topographic map is a representa- Activity Sheet #4: tion of a three-dimensional surface on On the poster is a topographic map a flat piece of paper. The digital eleva- of Salt Lake City. This lesson will help Which is higher, hill A or hill B? tion model on the poster is helpful in students learn how to read that map. (Answer: hill B) understanding topographic maps. Learning to use a topographic map is a difficult skill, because it requires stu- Which is steeper, hill A or hill B? Contour lines, sometimes called "level dents to visualize a three-dimensional (Answer: hill B) lines," join points of equal elevation. surface from a flat piece of paper. The closer together the contour lines Students need both practice and imag- 3. Compare a topographic map to a picture of the same place. Now have appear on a topographic map, the ination to learn to visualize hills and steeper the slope (assuming constant valleys from the contour lines on a the students look at the topographic of the same two hills. Say, "The contour intervals). topographic map. map lines you see on this map are called contour lines. Can you see why they Topographic maps have a variety of A digital terrain model of Salt Lake City uses, from planning the best route for is shown on the poster. -

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1

Survey of India Department of Science & Technology Rashtriya Manchitran Niti NATIONAL MAP POLICY 1. PREAMBLE All socio-economic developmental activities, conservation of natural resources, planning for disaster mitigation and infrastructure development require high quality spatial data. The advancements in digital technologies have now made it possible to use diverse spatial databases in an integrated manner. The responsibility for producing, maintaining and disseminating the topographic map database of the whole country, which is the foundation of all spatial data vests with the Survey of India (SOI). Recently, SOI has been mandated to take a leadership role in liberalizing access of spatial data to user groups without jeopardizing national security. To perform this role, the policy on dissemination of maps and spatial data needs to be clearly stated. 2. OBJECTIVES • To provide, maintain and allow access and make available the National Topographic Database (NTDB) of the SOI conforming to national standards. • To promote the use of geospatial knowledge and intelligence through partnerships and other mechanisms by all sections of the society and work towards a knowledge-based society. 3. TWO SERIES OF MAPS To ensure that in the furtherance of this policy, national security objectives are fully safeguarded, it has been decided that there will be two series of maps namely (a) Defence Series Maps (DSMs)- These will be the topographical maps (on Everest/WGS-84 Datum and Polyconic/UTM Projection) on various scales (with heights, contours and full content without dilution of accuracy). These will mainly cater for defence and national security requirements. This series of maps (in analogue or digital forms) for the entire country will be classified, as appropriate, and the guidelines regarding their use will be formulated by the Ministry of Defence. -

Geological and Seismic Evidence for the Tectonic Evolution of the NE Oman Continental Margin and Gulf of Oman GEOSPHERE, V

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Geological and seismic evidence for the tectonic evolution of the NE Oman continental margin and Gulf of Oman GEOSPHERE, v. 17, no. X Bruce Levell1, Michael Searle1, Adrian White1,*, Lauren Kedar1,†, Henk Droste1, and Mia Van Steenwinkel2 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3AN, UK https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02376.1 2Locquetstraat 11, Hombeek, 2811, Belgium 15 figures ABSTRACT Arabian shelf or platform (Glennie et al., 1973, 1974; Searle, 2007). Restoration CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] of the thrust sheets records several hundred kilometers of shortening in the Late Cretaceous obduction of the Semail ophiolite and underlying thrust Neo-Tethyan continental margin to slope (Sumeini complex), basin (Hawasina CITATION: Levell, B., Searle, M., White, A., Kedar, L., Droste, H., and Van Steenwinkel, M., 2021, Geological sheets of Neo-Tethyan oceanic sediments onto the submerged continental complex), and trench (Haybi complex) facies rocks during ophiolite emplace- and seismic evidence for the tectonic evolution of the margin of Oman involved thin-skinned SW-vergent thrusting above a thick ment (Searle, 1985, 2007; Cooper, 1988; Searle et al., 2004). The present-day NE Oman continental margin and Gulf of Oman: Geo- Guadalupian–Cenomanian shelf-carbonate sequence. A flexural foreland basin southwestward extent of the ophiolite and Hawasina complex thrust sheets is sphere, v. 17, no. X, p. 1– 22, https:// doi .org /10.1130 /GES02376.1. (Muti and Aruma Basin) developed due to the thrust loading. Newly available at least 150 km across the Arabian continental margin. The obduction, which seismic reflection data, tied to wells in the Gulf of Oman, suggest indirectly spanned the Cenomanian to Early Maastrichtian (ca 95–72 Ma; Searle et al., Science Editor: David E. -

Glacial Tectonics: a Deeper Perspective Robert M

Quaternary Science Reviews 19 (2000) 1391}1398 Glacial tectonics: a deeper perspective Robert M. Thorson* Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Connecticut, 345 Mansxeld Road (U-45), Storrs, CT 06269, USA Abstract The upper 5}10 km of the lithosphere is sensitive to slight changes ((0.1 MPa) in local stress caused by di!erential loading, #uid #ow, the mechanical transfer of strain between faults, and viscoelastic relaxation in the aesthenosphere. Lithospheric stresses induced by mass and #uid transfers associated with Quaternary ice sheets a!ected the tectonic regimes of stable cratons and active plate margins. In the latter case, it is di$cult to di!erentiate glacially induced fault displacements from nonglacial ones, particularly if residual glacial stresses are considered. Glaciotectonics, a sub-subdiscipline within Quaternary geology is historically focussed on reconstructing past glacier regimes and, by de"nition, does not include these e!ects. The term `glacial tectonicsa is hereby suggested for investigations focussed on the past and continuing in#uences of ice sheets on contemporary tectonics. ( 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction e!ects of glacial mass transfers is blurring the distinction between the study of tectonics, per se, and the study of Presently, there is a conceptual shift in the geosciences `glaciotectonicsa, which, historically, has been primarily away from increasing specialization, towards more inte- concerned with deformed glacial deposits. grative problems at global scales, a shift embodied by the In this paper I show how the physical coupling be- phrase `Earth System Sciencea (Kump et al., 1999). Si- tween glaciation and crustal deformation extends far multaneously, technologically driven advances in instru- beyond the decollement between ice and its substrate (i.e. -

Bare Bedrock Erosion Rates in the Central Appalachians, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 Bare Bedrock Erosion Rates in the Central Appalachians, Virginia Jennifer Whitten College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Whitten, Jennifer, "Bare Bedrock Erosion Rates in the Central Appalachians, Virginia" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 326. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/326 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BARE BEDROCK EROSION RATES IN THE CENTRAL APPALACHIANS, VIRGINIA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Science in Geology from The College of William and Mary by Jennifer Whitten Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Gregory Hancock, Director ________________________________________ Christopher Bailey ________________________________________ James Kaste ________________________________________ Scott Southworth Williamsburg, VA April 30, 2009 Table of Contents Abstract......................................................................................................................................................3 -

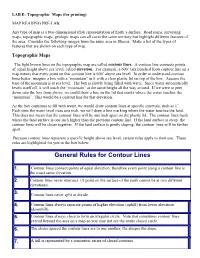

General Rules for Contour Lines

6/30/2015 EASC111LabEFor Printing LAB E: Topographic Maps (for printing) MAP READING PRELAB: Any type of map is a twodimensional (flat) representation of Earth’s surface. Road maps, surveying maps, topographic maps, geologic maps can all cover the same territory but highlight different features of the area. Consider the following images from the same area in Illinois. Make a list of the types of features that are shown on each type of map. Topographic Maps The light brown lines on the topographic map are called contour lines. A contour line connects points of equal height above sea level, called elevation. For example, a 600’ (six hundred foot) contour line on a map means that every point on that contour line is 600’ above sea level. In order to understand contour lines better, imagine a box with a “mountain” in it with a clear plastic lid on top of the box. Assume the base of the mountain is at sea level. The box is slowly being filled with water. Since water automatically levels itself off, it will touch the “mountain” at the same height all the way around. If we were to peer down into the box from above, we could draw a line on the lid that marks where the water touches the “mountain”. This would be a contour line for that elevation. As the box continues to fill with water, we would draw contour lines at specific intervals, such as 1”. Each time the water level rises one inch, we will draw a line marking where the water touches the land. -

Maps and Charts

Name:______________________________________ Maps and Charts Lab He had bought a large map representing the sea, without the least vestige of land And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be, a map they could all understand - Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark Map Projections: All maps and charts produce some degree of distortion when transferring the Earth's spherical surface to a flat piece of paper or computer screen. The ways that we deal with this distortion give us various types of map projections. Depending on the type of projection used, there may be distortion of distance, direction, shape and/or area. One type of projection may distort distances but correctly maintain directions, whereas another type may distort shape but maintain correct area. The type of information we need from a map determines which type of projection we might use. Below are two common projections among the many that exist. Can you tell what sort of distortion occurs with each projection? 1 Map Locations The latitude-longitude system is the standard system that we use to locate places on the Earth’s surface. The system uses a grid of intersecting east-west (latitude) and north-south (longitude) lines. Any point on Earth can be identified by the intersection of a line of latitude and a line of longitude. Lines of latitude: • also called “parallels” • equator = 0° latitude • increase N and S of the equator • range 0° to 90°N or 90°S Lines of longitude: • also called “meridians” • Prime Meridian = 0° longitude • increase E and W of the P.M. -

Sedimentary Stylolite Networks and Connectivity in Limestone

Sedimentary stylolite networks and connectivity in Limestone: Large-scale field observations and implications for structure evolution Leehee Laronne Ben-Itzhak, Einat Aharonov, Ziv Karcz, Maor Kaduri, Renaud Toussaint To cite this version: Leehee Laronne Ben-Itzhak, Einat Aharonov, Ziv Karcz, Maor Kaduri, Renaud Toussaint. Sed- imentary stylolite networks and connectivity in Limestone: Large-scale field observations and implications for structure evolution. Journal of Structural Geology, Elsevier, 2014, pp.online first. <10.1016/j.jsg.2014.02.010>. <hal-00961075v2> HAL Id: hal-00961075 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00961075v2 Submitted on 19 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. 1 2 Sedimentary stylolite networks and connectivity in 3 Limestone: Large-scale field observations and 4 implications for structure evolution 5 6 Laronne Ben-Itzhak L.1, Aharonov E.1, Karcz Z.2,*, 7 Kaduri M.1,** and Toussaint R.3,4 8 9 1 Institute of Earth Sciences, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 91904, Israel 10 2 ExxonMobil Upstream Research Company, Houston TX, 77027, U.S.A 11 3 Institut de Physique du Globe de Strasbourg, University of Strasbourg/EOST, CNRS, 5 rue 12 Descartes, F-67084 Strasbourg Cedex, France. -

Sedimentological Constraints on the Initial Uplift of the West Bogda Mountains in Mid-Permian

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Sedimentological constraints on the initial uplift of the West Bogda Mountains in Mid-Permian Received: 14 August 2017 Jian Wang1,2, Ying-chang Cao1,2, Xin-tong Wang1, Ke-yu Liu1,3, Zhu-kun Wang1 & Qi-song Xu1 Accepted: 9 January 2018 The Late Paleozoic is considered to be an important stage in the evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Published: xx xx xxxx Belt (CAOB). The Bogda Mountains, a northeastern branch of the Tianshan Mountains, record the complete Paleozoic history of the Tianshan orogenic belt. The tectonic and sedimentary evolution of the west Bogda area and the timing of initial uplift of the West Bogda Mountains were investigated based on detailed sedimentological study of outcrops, including lithology, sedimentary structures, rock and isotopic compositions and paleocurrent directions. At the end of the Early Permian, the West Bogda Trough was closed and an island arc was formed. The sedimentary and subsidence center of the Middle Permian inherited that of the Early Permian. The west Bogda area became an inherited catchment area, and developed a widespread shallow, deep and then shallow lacustrine succession during the Mid- Permian. At the end of the Mid-Permian, strong intracontinental collision caused the initial uplift of the West Bogda Mountains. Sedimentological evidence further confrmed that the West Bogda Mountains was a rift basin in the Carboniferous-Early Permian, and subsequently entered the Late Paleozoic large- scale intracontinental orogeny in the region. The Central Asia Orogenic Belt (CAOB) is the largest accretionary orogen on Earth, which was formed by the amalgamation of multiple micro-continents, island arcs and accretionary wedges1–5.