Indian Fable Literature; a Paper Read Before the Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

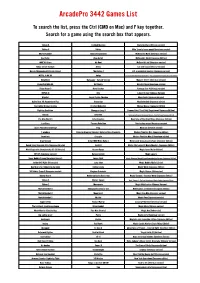

Arcadepro 3442 Games List

ArcadePro 3442 Games List To search the list, press the Ctrl (CMD on Mac) and F key together. Search for a game using the search box that appears. Tekken 6 Sindbad Mystery Mario Brothers (Chinese version) Tekken 5 Valtric Mike Tyson's heavy punch (American version) Mortal Kombat Youma Ninpou Chou McDonald's Mario (American version) Soul Eater Akuu Gallet McDonald's World (Japanese Edition) WWE All Stars Air Duel McDonald's kid (American version) Kidou Senshi Gundam Aliens Cat and mouse (Chinese version) Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact The Alphax Z U.S. presidential election (Japanese version) METAL SLUG XX Amigo U.S. Crosscutting Questions and Answers - The Largest Battle in History (Japanese Edition) BLAZBLUE Batsugun - Special Version Monster Street (American version) Basketball NBA 06 Battlantis Mendel Palace (American version) Ridge Racer 2 Bone Crusher Fantasy Star 4 (Chinese version) INITIAL D Brix Labyrinth Seal (Chinese Version) WipeOut Janpai Puzzle Choukou Maze Suite (Japanese Version) Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus Crazy Cop Muddleheaded (Japanese edition) Soulcalibur Broken Destiny Crusher Makochan Mickey Mouse (Japanese Edition) Fighting Evolution Zhongguo Long II Famous Gate! Third Field Department (Japanese Edition) Bleach Drive Out Famous gate! Dorgussi Responding Mission - Hard Six People (Japanese Edition) Pac Man World 3 Extermination Biography of Star Eight Dogs (Japanese Edition) LocoRoco Farmers Rebellion Star hockey on ice (American version) Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge Frog Moai Jun (Chinese version) 7 wonders -

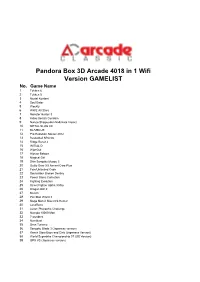

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

Download The

BOOK REVIEWS 163 work and to outgrow the strong European bias, the editors’ efforts would bear good fruit. Peter Knecht JAPAN Kurosawa Fumiko. Pfauendarstellungen in Kunst und Kunstgewerbe Japans. Pfauensymbolik und ihre Darstellungsformen in der ostasiatischen Kunst. [Representations of the peacock in Japanese art and crafts. Symbolism of the peacock and its expression in Eastasian art]. Europaische Hoch- schulschriften Reihe X X V III, Kunstgeschichte, Kunstgeschichte Band 7 1 . Frankfurt a/M, Germany: Peter Lang, 1987. 300 pages, 245 il lustrations. Paper sFr. 65.00; ISBN 3-8204-9743-9, ISSN 0721-3567. (In German) On my second day in Japan years ago I was treated to a whirlwind tour of Kyoto. One of the first sights was the Nijo Castle and its gardens. Much to my surprise I found peacocks represented in various forms throughout the building. What could they mean? In the West the peacock, often gracing baptistries or shown in connection with Eucharistic symbols, was a symbol of eternal life / paradise for the early Chris tians. In more profane circumstances the eye-like tail feathers represented bad luck, and in general the peacock degenerated to a symbol of vainglory and pride. What was the peacock for the East, specifically for Japan? In 1974 Asian Folklore Studies pub lished a long article on the peacock in India, its native territory. But other inquiries only led to the general answer that the peacock came to Japan through China and is often mixed up with China’s mythological bird, the “ Phoenix.” Fumiko Kurosawa takes up this question in her book and treats the reader, un familiar with Chinese and Japanese sources, to representations of the peacock in paint ings, lacquerware, and wood and metal work. -

Japanese Women, Hong Kong Films, and Transcultural Fandom

SOME OF US ARE LOOKING AT THE STARS: JAPANESE WOMEN, HONG KONG FILMS, AND TRANSCULTURAL FANDOM Lori Hitchcock Morimoto Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Culture Indiana University April 2011 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________________ Prof. Barbara Klinger, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Gregory Waller, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michael Curtin, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michiko Suzuki, Ph.D. Date of Oral Examination: April 6, 2011 ii © 2011 Lori Hitchcock Morimoto ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii For Michael, who has had a long “year, two at the most.” iv Acknowledgements Writing is a solitary pursuit, but I have found that it takes a village to make a dissertation. I am indebted to my advisor, Barbara Klinger, for her insightful critique, infinite patience, and unflagging enthusiasm for this project. Gratitude goes to Michael Curtin, who saw promise in my early work and has continued to mentor me through several iterations of his own academic career. Gregory Waller’s interest in my research has been gratifying and encouraging, and I am most appreciative of Michiko Suzuki’s interest, guidance, and insights. Richard Bauman and Sumie Jones were enthusiastic readers of early work leading to this dissertation, and I am grateful for their comments and critique along the way. I would also like to thank Joan Hawkins for her enduring support during her tenure as Director of Graduate Studies in CMCL and beyond, as well as for the insights of her dissertation support group. -

Alternative Titles Index

VHD Index - 02 9/29/04 4:43 PM Page 715 Alternative Titles Index While it's true that we couldn't include every Asian cult flick in this slim little vol- ume—heck, there's dozens being dug out of vaults and slapped onto video as you read this—the one you're looking for just might be in here under a title you didn't know about. Most of these films have been released under more than one title, and while we've done our best to use the one that's most likely to be familiar, that doesn't guarantee you aren't trying to find Crippled Avengers and don't know we've got it as The Return of the 5 Deadly Venoms. And so, we've gathered as many alternative titles as we can find, including their original language title(s), and arranged them in alphabetical order in this index to help you out. Remember, English language articles ("a", "an", "the") are ignored in the sort, but foreign articles are NOT ignored. Hey, my Japanese is a little rusty, and some languages just don't have articles. A Fei Zheng Chuan Aau Chin Adventure of Gargan- Ai Shang Wo Ba An Zhan See Days of Being Wild See Running out of tuas See Gimme Gimme See Running out of (1990) Time (1999) See War of the Gargan- (2001) Time (1999) tuas (1966) A Foo Aau Chin 2 Ai Yu Cheng An Zhan 2 See A Fighter’s Blues See Running out of Adventure of Shaolin See A War Named See Running out of (2000) Time 2 (2001) See Five Elements of Desire (2000) Time 2 (2001) Kung Fu (1978) A Gai Waak Ang Kwong Ang Aau Dut Air Battle of the Big See Project A (1983) Kwong Ying Ji Dut See The Longest Nite The Adventures of Cha- Monsters: Gamera vs. -

Bulletin State Teachers College Volume XXXV Issue 1, February 1949 Longwood University

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Alumni Newsletters & Bulletins Library, Special Collections, and Archives 2-1949 Bulletin State Teachers College Volume XXXV issue 1, February 1949 Longwood University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/alumni Recommended Citation Longwood University, "Bulletin State Teachers College Volume XXXV issue 1, February 1949" (1949). Alumni Newsletters & Bulletins. 7. http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/alumni/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library, Special Collections, and Archives at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Newsletters & Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bulletin of ig) STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE Farmville, Virginia ALUMNAE NEWS Volume XXXV FEBRUARY. 1949 Number I Jrresiident \_j^J\CSiS't.GTL S As I enter upon my thifd session at Farmville, I welcome the opportunity to send a word of greeting to our alumnae and to report some of Ml6SS3.^V^ the accomplishments of the last twelve months. Now that I have attained "Junior" status, I can really look forward to assuming the full dignity of an alumnus in a relatively short time. The College has enrolled an excellent class of freshmen in so far as quality, ability and charm are concerned. We have continued our plan of careful selection of candidates for admission and had to reject relatively few as compared with a year ago. Apparently, only gii'ls of good quality applied. It becomes increasingly necessary, however, for our fine group of alumnae to become more active than ever in interesting girls of ability in coming to S.T.C. -

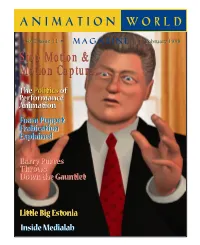

Stop Motion & Motion Capture Stop Motion

VolVol 22 IssueIssue 1111 February 1998 Stop Motion & Motion Capture The Politics of Performance Animation FoamFoam PuppetPuppet FrabicationFrabication ExplainedExplained BarryBarry Purves Purves ThrowsThrows DownDown thethe GauntletGauntlet Little Big Estonia InsideInside MedialabMedialab Table of Contents February, 1998 Vol. 2, No. 11 4 Editor’s Notebook Animation and its many changing faces... 5 Letters: [email protected] STOP-MOTION & MOTION-CAPTURE 6 Who’s Data Is That Anyway? Gregory Peter Panos, founding co-director of the Performance Animation Society, describes a new fron- tier of dilemmas, the politics of performance animation. 9 Boldly Throwing Down the Gauntlet In our premier issue, acclaimed stop-motion animator Barry J.C. Purves shared his sentiments on the coming of the computer. Now Barry’s back to share his thoughts on the last two years that have been both exhilarating and disappointing for him. 14 A Conversation With... In a small, quiet cafe, motion-capture pioneer Chris Walker and outrageous stop-motion animator Corky Quakenbush got together for lunch and discovered that even though their techniques may appear to be night and day, they actually have a lot in common. 21 At Last, Foam Puppet Fabrication Explained! How does one build an armature from scratch and end up with a professional foam puppet? Tom Brierton is here to take us through the steps and offer advice. 27 Little Big Estonia:The Nukufilm Studio On the 40th anniversary of Estonia’s Nukufilm, Heikki Jokinen went for a visit to profile the puppet ani- mation studio and their place in the post-Soviet world. 31 Wallace & Gromit Spur Worldwide Licensing Activity Karen Raugust takes a look at the marketing machine behind everyone’s favorite clay characters, Wallace & Gromit. -

Game Title: Works? Video: Synopsis By: Manual Notes, Useful Information

Game Title: Works? Video: Synopsis By: Manual Notes, Useful Information. Website: NES TEST: http://www.megaupload.com/?d=JQKTAXT0 (1.1) USA LICENSED [*649 Videos COMPLETE!*] [*Artwork/Synopsis Complete*] 3-D Battles of WorldRunner Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y 8 Eyes Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y 10-Yard Fight Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y 720 Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y 1942 Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y 1943 Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y A Boy and His Blob Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y Played to the end without problems. ~Rx A Nightmare On Elm Street Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y Played to the end without problems. ~Rx Abadox Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y AD&D Dragon Strike Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y AD&D Heroes of the Lance Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y AD&D Hillsfar Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y AD&D Pool of Radiance Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y Addams Family - Pugslys Scavenger Hunt Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y Addam's Family - Uncle Fester's Quest Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y Addams Family Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y Adventures in the Magic Kingdom Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y Adventures of Dino Riki Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9999 Y Adventures of Lolo I Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9,999 Y Played to the end with no problems. ~Rx Adventures of Lolo II Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9,999 Y Adventures of Lolo III Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9,999 Y Adventures of Rad Gravity Works. ~Rx emumovies Gilles9,999 Y Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle Works. ~Rx emumovies Ressurectionx Y Adventures of Tom Sawyer Works. -

Realism" in Graeco-Roman Fable As Depicted

MAJORITY REAL: "REALISM" IN GRAECO-ROMAN FABLE AS DEPICTED THROUGH THE CROW AND RAVEN MAJORITY REAL: "REALISM" IN GRAECO-ROMAN FABLE AS DEPICTED THROUGH THE CROW AND RAVEN By DAVID WALLACE-HARE, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Classics McMaster University © Copyright by David Wallace-Hare, August 2012 McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS IN CLASSICS (2012) Hamilton, Ontario (Classics) TITLE: Majority Real: "Realism" in Graeco-Roman Fable As Depicted Through the Crow and Raven AUTHOR: David Wallace-Hare, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor P.M. Murgatroyd NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 133 ii ABSTRACT David Wallace-Hare: Majority Real: "Realism" in Graeco-Roman Fable As Depicted Through the Crow and Raven (Under the direction of Professor Paul Murgatroyd, Professor Sean Corner, and Professor Claude Eilers) The role of realism in the depiction of animals in Greaco-Roman fable is investigated. The crow and the raven have been chosen as the prism through which the investigation is carried out. Fable will be shown to be a genre founded on a contextually realistic depiction of animals, and this may especially be seen in the corvid fables. Realism must, however, be understood contextually, as what constitutes a realistic depiction of crows and ravens in Graeco-Roman times is quite different than what one would encounter at present. As a result of which the crow and raven are marked by attributes ranging from cleverness, parenting ability, resistance to weather, vocal mimicry, longevity, and augural significance, amongst a host of other characteristics which sometimes coincide with modern views but often do not. -

Latest Issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction

"0 () THE MAGAZINE OF Fantosv AND Science Fiction NOVEMBER.. ••• AND CALL ME CONRAD by ROGER ZELAZNY A FEW KINDRED SPIRITS by JOHN CHRISTOPHER ISAAC ASIMOV JUDITH MERRIL DUNE By FRANK HERBERT. This gripping novel of the distant future, by the author of The Dra~ton in the Sea, cen ters around a man whose son happens to be the possible key to all human rule, power, and indeed knowledge! It is a dazzling tour de force that blends the power of the past with a sweeping vision of the fut-ure. $5.95 AGENT OF THE TERRAN EMPI RE By POUL ANDERSON. A two:.time win ner of the "Hugo" Award for science fiction writing introduces Sir D ominic Flandry - Captain in Earth's Imperial Naval Intelligence Corps and the "Agent 007" of the future. Here are swashbuckling battles galore as Flan dry fights his way through a clutch of enemies - human and non-human. $3.95 FLANDRY OF TERRA By PoUL ANDERSON. Captain Flandry mans the ramparts of the universe once again in these swift-paced adventures. This time he is up against a hundred foot-long enemy agent, a catlike beau ty, and a ruthless scientific tyranny. $3.95 A NICE DAY FOR SCREAMING And Other Tales of the Hub By JAMES SCHMITZ. Incredible adven tures from the central nexus of the Galactic Civilization in the year 3500 A.D. $3.95 TO WORLDS BEYOND Tales of the Future By RoBERT SILVERBERG. Foreword by ISAAC ASIMOV. A great master of S-F shows us our descendants in action among the stars, in provocative stories that pose such questions as: Can we out-invent intelligent aliens? What is· the definition of a zoo - and who be longs behind the bars, we or they? $3.95 Now at your bookstore CHILTON BOOKS, 227 So. -

1 ESSENCE of NEETI CHANDRIKA (Stories on Morality for Childen With

ESSENCE OF NEETI CHANDRIKA (Stories on Morality For Childen with emphatic appeal to Elders ) Edited and translated by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager of India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi now at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:- Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras* Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana*- Also Essence of Knowledge of -

Tekken2 3D Tekken3 3D Street Fighter 3D Mortalkombat2 3D

Tekken2 3D Tekken3 3D Street Fighter 3D MortalKombat2 3D Mortal Kombat Trilogy 3D MortalKombat4 3D RivalSchools 3D Strider2 3D BloodyRoarII 3D raystorm 3D Bomberman 3D Pepsi-Man 3D Hyahujuu Sentai Gaoranger 3D X-Men vs. Street Fighter EX Edition 3D StreetFighterEX2 PLUS 3D BubbleBobble 2 3D All-StarSlammin Dodgeball 3D All-StarTennis 99 3D Rockmanx 8 3D Gear Fighter Dendoh 3D Choaniki 3D Capcom vs.SNK-Millennium Fight 2000 Pro 3D Shiritsu Justice Gakuen - Legion of Heroes 3D Slap Happy Rhythm Busters 3D Hermie Hopperhead 3D Groove Adventure Rave 3D Kakuge-Yaro: Fighting Game Creator 3D Kamen Rider Kuuga 3D Kamen Rider Kuuga 2 3D Jikkyou Powerfull Pro Yakyuu 97 3D 102Dalmations Puppies To The Rescue 3D Fast angel 3D Jojo's Bizarre Adventure 3D Ms. Pacman-Maze Madness 3D Advanced V.G 3D Advanced V.G2 3D Air Hockey 3D Gundam Battle Assault 2 3D PocketFighter 3D Boxing 3D Asuka 120% Limited: Burning Fest. Limited 3D Pro Evolution Soccer 3D Samurai Deeper Kyo 3D Battle Arena Toshinden 3D Kensea-Sacred Fist 3D Smash Court3 3D Single Baskball 3D PanzerBandit 3D Sonic Wings Special 3D The Contra Adventure 3D brapboysB.Rap 3D Ultimate Mortal Kombat 3 3D The Legend of Silkroad 3D Street Fighter3·New Generation 3D Street Fighter 3 2nd Impact: Giant Attack 3D Street Fighter 3 3rd Strike 3D Street Fighter 3 3rd Strike(future battle) 3D Street Fighter 3 3Rd S 3D KOF97 KOF98 KOF98C KOF99 K0F2000 K0F2001 K0F2002 K0F2003 K0F94 K0F95 K0F96 K0F95+ K0F96+ KOF97 10th Ann4ersary K0F97 Plus K0F97 Plus 2003 KOF97 Oroshi plus K0F98 Ultimate K0F98 Ultra Leona K0F99