An Analysis of Image Restoration Strategies and Content Variables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the U.S. Christian Right Is Transforming Sexual Politics in Africa

Colonizing African Values How the U.S. Christian Right is Transforming Sexual Politics in Africa A PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL RESEARCH ASSOCIATES BY KAPYA JOHN KAOMA Political Research Associates (PRA) is a progressive think tank devoted to supporting movements that build a more just and inclusive democratic society. We expose movements, institutions, and ideologies that undermine human rights. PRA seeks to advance progressive thinking and action by providing research-based information, analysis, and referrals. Copyright ©2012 Political Research Associates Kaoma, Kapya John. ISBN-10: 0-915987-26-0 ISBN-13: 978-0-915987-26-9 Design by: Mindflash Advertising Photographs by: Religion Dispatches, Michele Siblioni/AFP/Getty Images, Mark Taylor/markn3tel/Flickr This research was made possible by the generous support of the Arcus Foundation and the Wallace Global Fund. Political Research Associates 1310 Broadway, Suite 201 Somerville, MA 02144-1837 www.publiceye.org Colonizing African Values How the U.S. Christian Right is Transforming Sexual Politics in Africa A PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL RESEARCH ASSOCIATES BY KAPYA KAOMA POLITICAL RESEARCH ASSOCIATES i Colonizing African Values - How the U.S. Christian Right is Transforming Sexual Politics in Africa Foreword ganda’s infamous 2009 Anti-Homosexuality Bill, onstrates in Colonizing African Values that the Ameri- which would institute the death penalty for a can culture wars in Africa are growing hotter. Tracing U new and surreal category of offenses dubbed conflicts over homosexuality and women’s repro- “aggravated homosexuality,” captured international ductive autonomy back to their sources, Kaoma has headlines for months. The human rights community uncovered the expanding influence of an interde- and the Obama administration responded forcefully, nominational cast of conservative American inter- the bill was tabled, and the story largely receded ests. -

GA Company List

List of CA Grants & Annuities Companies CA Company Name Company Code AARP FOUNDATION G4857 ACLU FOUNDATION OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA G2891 ACTORS' FUND OF AMERICA (THE) G5084 ADVENTIST FRONTIER MISSIONS, INC. G4797 AFRICA INLAND MISSION INTERNATIONAL, INC. G4921 ALBANY MEDICAL CENTER HOSPITAL G5892 ALBANY MEDICAL COLLEGE G5891 ALLEGHENY COLLEGE G5977 ALLIANCE HEALTHCARE FOUNDATION G4616 ALTA BATES SUMMIT FOUNDATION G4349 ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE AND RELATED DISORDERS ASSOCIATION, INC. G4701 AMERICAN ASSOCIATES, BEN-GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV, INC. G5134 AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY WOMEN, INC. G5870 AMERICAN BAPTIST FOUNDATION G5049 AMERICAN BAPTIST HOMES FOUNDATION OF THE WEST, INC. G2650 AMERICAN BAPTIST SEMINARY OF THE WEST G2651 AMERICAN BIBLE SOCIETY G2652 AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY, INC. G4420 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, INC. G5590 AMERICAN COMMITTEE FOR THE WEIZMANN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE, INC. G4480 AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION G5105 AMERICAN FRIENDS OF MAGEN DAVID ADOM G6220 AMERICAN FRIENDS OF TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY, INC. G4840 AMERICAN FRIENDS OF THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY, INC. G4957 AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE, INCORPORATED G2653 AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, INC. G3598 AMERICAN HUMANE ASSOCIATION (THE) G5163 AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR CANCER RESEARCH (THE) G4684 AMERICAN KIDNEY FUND, INC. G4643 AMERICAN LEBANESE SYRIAN ASSOCIATED CHARITIES, INC. G4610 AMERICAN LUNG ASSOCIATION G4282 AMERICAN MISSIONARY FELLOWSHIP G2656 AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR TECHNION-ISRAEL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, INC. G5910 AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR THE -

Tabalujan, Benny Simon (2020) Improving Church Governance: Lessons from Governance Failures in Different Church Polities

Tabalujan, Benny Simon (2020) Improving church governance: Lessons from governance failures in different church polities. MTh(R) thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/81403/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Improving Church Governance Lessons from Governance Failures in Different Church Polities by Benny Simon TABALUJAN A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Theology (University of Glasgow) Edinburgh Theological Seminary 10 December 2019 © Benny Tabalujan, 2019 i Abstract This thesis focuses on the question as to whether using a particular church polity raises the likelihood of governance failure. Using the case study research method, I examine six case studies of church governance failures reported in the past two decades in the English media of mainly Western jurisdictions. The six case studies involve churches in the United States, Australia, Honduras, and Singapore. Three of the case studies involve sexual matters while another three involve financial matters. For each type of misconduct or alleged misconduct, one case study is chosen involving a church with congregational polity, presbyteral polity, and episcopal polity, respectively. -

Minister in Gay Prostitution Scandal to Make 'Groundbreaking' Announcement Recommend 89 People Recommend This

EDITION: U.S. INTERNATIONAL Sign up Log in Home Video NewsPulse U.S. World Politics Justice Entertainment Tech Health Living Travel Opinion iReport Money Sports Feedback Minister in gay prostitution scandal to make 'groundbreaking' announcement Recommend 89 people recommend this. By the CNN Wire Staff June 2, 2010 1:56 a.m. EDT NewsPulse Most popular stories right now Ted Koppel mourns son's death Stuck blade stalls BP effort to STORY HIGHLIGHTS (CNN) -- Ted Haggard, the megachurch pastor and former National cap well Ted Haggard's career as a Association of Evangelicals chief whose career was undone by a gay pastor went south after a sex prostitution and drugs scandal in 2006, is expected to talk about the UK police find body believed to and drugs scandal in 2006 next step in his career Wednesday. be suspected Haggard admitted to the sex 40 years of marriage, then the allegations, but said he tossed With his family by his side at his Colorado Springs home, Haggard is the drugs separation expected to a make "surprise groundbreaking" announcement, He also stepped aside as pastor according to a news statement Tuesday. A jazzy wedding for 'Glee's' of the 14,000-member New Life Church Jane Lynch In 2006, Haggard admitted he had received a massage from a Explore the news with NewsPulse » Denver, Colorado, man who claimed the prominent pastor had paid him for sex over three years. Haggard also admitted he had bought methamphetamine but that he threw it away. After the allegations were made public, Haggard resigned as president of the influential National Association of Evangelicals, an umbrella group representing more than 45,000 churches with 30 million members. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

“Loving the Sinner, Hating the Sin”: an Analysis of American

1 “LOVING THE SINNER, HATING THE SIN”: AN ANALYSIS OF AMERICAN MEGACHURCH RHETORIC OF HOMOSEXUALITY Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Ann Duncan May/2014 2 Introduction Recently the issue of homosexuality has come to represent a majorly divisive factor within American Christianity as more and more churches are defining their boundaries, or lack thereof, at homosexuality: many congregations believe that practicing homosexuality is not an acceptable aspect of one’s life that will allow passage into God’s Kingdom or salvation. Within megachurches, Protestant churches having at least 2,000 attendees per week, homosexuality often presents itself as a divisive and controversial issue. Megachurches tend to be situated on the more conservative and evangelical end of the spectrum of Protestant Christianity and, therefore, many of their congregations have expressed disapproval of homosexuality; they preach doctrines providing content for rhetoric following the guidelines of sexual purity as follows from divine law within their congregations. These doctrines include the biblical literalist approach to abiding by divine law, the presence of sin in today’s world, and the conscious choice to continue living a life in sin. It is through the combination of these doctrines, one choosing to act in a sinful manner going against the divine law accepted when one takes a literal approach to the Bible, which allows megachurches to arrive at the conclusion that the “homosexual lifestyle” constitutes a sin worthy of condemnation. However, megachurches are also using rhetoric of love and acceptance regardless of sexuality. -

Attachment a Fm Noncommercial Educational Mx

ATTACHMENT A FM NONCOMMERCIAL EDUCATIONAL MX GROUPS FOR COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS MX LEAD GROUP CUTOFF FILE NUMBER DATE NUMBER CITY ST APPLICANT 88031E 08/22/84 A BPED 19840322CA BATON ROUGE LA REAL LIFE EDUCATIONAL FOUND. OF BATON ROUGE, INC. 88031E BPED 19840822IF BATON ROUGE LA JIMMY SWAGGART MINISTRIES 880611 01/10/90 A BPED 19880610ML REDDING CA THE UNIV.FOUND. CA STATE UNIV, CHICO 880611 B BPED 19900129MH REDDING CA STATE OF OREGON 89101E 12/07/93 A BPED 19891019MA CROWN POINT IN HYLES-ANDERSON COLLEGE 89101E B BPED 19910409MF CROWN POINT IN THE MOODY BIBLE INSTITUTE 92102E 03/24/93 A BPED 19921026MA WHITEHALL OH LOU SMITH MINISTRIES, INC. 92102E A BPED 19921029MB COLUMBUS OH CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING SERVICES, INC 92102E B BPED 19921104MA COLUMBUS OH THE CEDARVILLE COLLEGE 94106E 07/14/95 A BPED 19941026MA NORMAN OK AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 94106E B BPED 19950714MD NORMAN OK SISTER SHERRY LYNN FOUNDATION INC 941116 03/28/96 A BPED 19941114MA ASHLAND KY AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 941116 B BPED 19960328MC ASHLAND KY POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 941116 B BPED 19960328MI HURRICANE WV POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 94114E 11/08/95 A BPED 19941103MC BRISTOL VA AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 94114E B BPED 19951023IB EMORY VA EMORY & HENRY COLLEGE 94114E B BPED 19951108NC BRISTOL VA VIRGINIA TECH FOUNDATION, INC. 94123E 05/24/95 A BPED 19941209MB OTTUMWA IA GRASSROOTS BROADCASTING, CO., INC. 94123E B BPED 19950213MB OTTUMWA IA IOWA ST UN OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 94123E B BPED 19950515ML FAIRFIELD IA AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 950215 05/03/96 A BPED 19950210MA MCCLOUD CA SOUTHERN OREGON STATE COLLEGE 950215 B BPED 19960503MG MCCLOUD CA FATIMA RESPONSE INC DBA 95031E 07/14/95 A BPED 19950327MA REDDING CA CHRISTIAN ARTS AND EDUCATION, INC. -

PAT ROBERTSON TELEVANGELIST SUMMARIES March 1987

TELEVANGELIST SUMMARIES March 1987 PAT ROBERTSON Bakker scandal ••.•..•••.•• • •• 46-48 Mobile, AL textbook case. • ••• 30-37 700 CLUB BENNET, WILLIAM School-based health clinics .• ••• 37 Gay rights .••.• .37 Welfare reform ••• • •••••• 38 School prayer ••• • •••• 38-39 JERRY FALWELL Bakker scandal ........... •••• 48-49 Bishop Desmond Tutu •• • ••• 39 PTL • ••..••.•.••••••. • 44-45 JIMMY SWAGGART Bakker scandal .• .41-43 Fundraising •. .45 Israel. •• 49 Jews •••• • ••• 40 JAMES ROBISON Media • ...••.•.•.•••.................•••••..•.......•....... 44 THE 700 CLUB March 6, 1987 MOBILE, AL Reverend Pat Robertson: "For years, many Christian parents have thought that the public ~chools were teaching humanistic values that were quite different from what they wanted their children to learn. Now the concept of humanism and the humanities is very noble. To be humanitarianism (sic) is good. But secular humanism is actually a type of religion. It's actually atheism in a new guise. Well, in Mobile, Alabama, 624 parents decided to do something about it. They were joined of course in that part of the 624 were teachers and students." NARRATOR: "It may go down as the religious liberty case of the twentieth century ••• The decision marks the first time, humanism, including secular humanism, has been recognized and defined as a religion. That means it can no longer be allowed a preferred position in public education but now, legally, will have to be treated with strict neutrality, as required of all religions by the Supreme Court." Attorney for the Plaintiffs, Tom Parker: "Not only does this decision ban the use of certain books in the state of Alabama which violate Constitutional rights, it also establishes some guidelines which could be used by state textbook committees or by concerned parents. -

The Christian Coalition in the Life Cycle of the Religious Right

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1997 Defying the odds: The Christian Coalition in the life cycle of the Religious Right Kathleen S Espin University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Espin, Kathleen S, "Defying the odds: The Christian Coalition in the life cycle of the Religious Right" (1997). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 3321. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/CQHQ-ABU5 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text direct^ from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiic^ udnle others may be fix>m any type o f computer printer. The qnalityr of this reproduction is dependent npon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversety afikct reproduction. -

Fortress Repertoire

FORTRESS REPERTOIRE OLDIES AND MOTOWN Ain’t No Mountain High Enough – Marvin My Girl – The Temptations Gaye & Tammi Terrell My Guy – Mary Wells Baby Love – The Supremes A Natural Woman (You Make Me Feel Like) Dancing in the Street – Martha & the – Aretha Franklin Vandellas Reach Out I’ll Be There – The Four Tops Don’t Leave Me This Way – Thelma Houston Rescue Me – Standard Respect – Aretha Franklin Funky Good Time – James Brown Georgia – Ray Charles Rock Steady – Aretha Franklin Heat Wave – Martha & the Vandellas Rockin’ Robin – Michael Jackson Shout – Isley Brothers I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie Honey Bunch) – The Four Tops Signed, Sealed, Delivered – Stevie Wonder I Heard It Through the Grapevine – Gladys Son of a Preacher Man – Dusty Springfield Knight & the Pips Stop! In the Name of Love – The Supremes I Heard It Through the Grapevine – Marvin Superstition – Stevie Wonder Gaye The Tears of a Clown – Smokey Robinson I Want You Back – Jackson 5 & the Miracles I’ll Be There – Jackson 5 Time of My Life (I’ve Had The) – Bill Medley I’m Coming Out – Diana Ross & Jennifer Warnes It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World – James Tutti Frutti – Little Richard Brown Think – Aretha Franklin Johnny B. Goode – Chuck Berry Under the Boardwalk – The Drifters Just My Imagination (Running Away with Upside Down – Diana Ross Me) – The Temptations Uptight (Everything’s Alright) – Stevie Let’s Get It On – Marvin Gaye Wonder Love Hangover – Diana Ross We Are Family – Sister Sledge Midnight Train to Georgia – Gladys Knight & What’s Going On – Marvin Gaye the Pips -

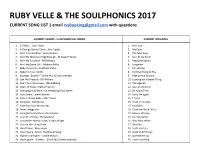

SONG LIST | Email [email protected] with Questions

RUBY VELLE & THE SOULPHONICS 2017 CURRENT SONG LIST | email [email protected] with questions CURRENT COVERS - In ALPHABETICAL ORDER CURRENT ORIGINALS 1. 25 Miles - Edwin Starr 1. Heartlite 2. A Change Gonna Come - Sam Cooke 2. My Dear 3. Ain’t It Funky Now - James Brown 3. The Man Says 4. Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - M.Gaye/T.Terrell 4. Soul of the Earth 5. Ain’t No Sunshine - Bill Withers 5. Medicine Spoon 6. Am I the Same Girl - Barbara Acklin 6. Longview 7. Baby I Love You- Aretha Franklin 7. Mr. Wrong 8. Baby It’s You - Smith 8. Coming Home to You 9. Bootleg - Booker T. & the MG’s (instrumental) 9. Feet on the Ground 10. Can We Pretend - Bill Withers 10. Looking for a Better Thing 11. Can’t Turn You Loose - Otis Redding 11. The Agenda 12. Chain of Fools- Aretha Franklin 12. Soul of the Earth 13. Champagne & Wine - Otis Redding/ Etta James 13. Its About Time 14. Cold Sweat - James Brown 14. Used Me again 15. Comin’ Home Baby - Mel Torme 15. I Tried 16. Darkness- Tab Benoit 16. Tried on A Smile 17. Fade Into You- Mazzy Star 17. Just Blink 18. Fever- Peggy Lee 18. Close the Book On Us 19. Georgia On My Mind - Ray Charles 19. Broken Women 20. Grab This Thing - The Markeys 20. Call My Name 21. Grapevine- Marvin Gaye/ Gladys Knight 21. Way Back When 22. Groove Me - King Floyd 22. Shackles 23. Hard Times - Baby Huey 23. Lost Lady Usa 24. Hava Nagila- Jewish Traditional Song 24. -

© 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat

Numbers Song Title © 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat. Melanie Blatt 409 Beach Boys, The 911 Wyclef Jean & Mary J Blige 1969 Keith Stegall 1979 Smashing Pumpkins, The 1982 Randy Travis 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 1999 Wilkinsons, The 5678 Step #1 Crush Garbage 1, 2 Step Ciara Feat. Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys, The 100 Years Five For Fighting 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis & The News 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 18 & Life Skid Row 18 Till I Die Bryan Adams 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin 19-2000 Gorillaz 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 20th Century Fox Doors, The 21 Questions 50 Cent Feat Nate Dogg 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band, The 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 25 Miles Edwin Starr 25 Minutes Michael Learns To Rock 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 29 Nights Danni Leigh 29 Palms Robert Plant 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 30 Days In The Hole Humble Pie 30,000 Pounds Of Bananas Harry Chapin 32 Flavours Alana Davis 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Seasons Of Loneiness Boyz 2 Men 4 To 1 In Atlanta Tracy Byrd 4+20 Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young 42nd Street Broadway Show “42nd Street” 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 4th Of July Shooter Jennings 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 50,000 Names George Jones 50/50 Lemar 500 Miles (Away From Home) Bobby Bare