Relative Vihuela Tunings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Rippling Notes” to the Federal Way Performing Arts & Event Center Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 Pm

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT August 23, 2017 Scott Abts Marketing Coordinator [email protected] DOWNLOAD IMAGES & VIDEO HERE 253-835-7022 MASTSER TIMPLE MUSICIAN GERMÁN LÓPEZ BRINGS “RIPPLING NOTES” TO THE FEDERAL WAY PERFORMING ARTS & EVENT CENTER SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 17 AT 3:00 PM The Performing Arts & Event Center of Federal Way welcomes Germán (Pronounced: Herman) López, Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 PM. On stage with guitarist Antonio Toledo, Germán harnesses the grit of Spanish flamenco, the structure of West African rhythms, the flourishing spirit of jazz, and an innovative 21st century approach to performing “island music.” His principal instrument is one of the grandfathers of the ‘ukelele’, and part of the same instrumental family that includes the cavaquinho, the cuatro and the charango. Germán López’s music has been praised for “entrancing” performances of “delicately rippling notes” (Huffington Post), notes that flow from musical traditions uniting Spain, Africa, and the New World. The “timple” is a diminutive 5 stringed instrument intrinsic to music of the Canary Islands. Of all the hypotheses that exist about the origin of the “timple”, the most widely accepted is that it descends from the European baroque guitar, smaller than the classical guitar, and with five strings. Tickets for Germán López are on sale now at www.fwpaec.org or by calling 2535-835-7010. The Performing Arts and Event Center is located at 31510 Pete von Reichbauer Way South, Federal Way, WA 98003. We’ll see you at the show! About the PAEC The Performing Arts & Event Center opened August of 2017 as the South King County premier center for entertainment in the region. -

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Nafme Council for Guitar

Guitar Best Practices Years 1, 2, 3 and 4 Many schools today offer guitar classes and guitar ensembles as a form of music instruction. While guitar is a popular music choice for students to take, there are many teachers offering instruction where guitar is their secondary instrument. The NAfME Guitar Council collaborated and compiled lists of Guitar Best Practices for each year of study. They comprise a set of technical skills, music experiences, and music theory knowledge that guitar students should know through their scholastic career. As a Guitar Council, we have taken careful consideration to ensure that the lists are applicable to middle school and high school guitar class instruction, and may be covered through a wide variety of method books and music styles (classical, country, folk, jazz, pop). All items on the list can be performed on acoustic, classical, and/or electric guitars. NAfME Council for Guitar Education Best Practices Outline for a Year One Guitar Class YEAR ONE - At the completion of year one, students will be able to: 1. Perform using correct sitting posture and appropriate hand positions 2. Play a sixteen measure melody composed with eighth notes at a moderate tempo using alternate picking 3. Read standard music notation and play on all six strings in first position up to the fourth fret 4. Play melodies in the keys C major, a minor, G major, e minor, D major, b minor, F major and d minor 5. Play one octave scales including C major, G major, A major, D major and E major in first position 6. -

Ficha Técnica

FICHA TÉCNICA INSTRUMENTOS MUSICALES INSTRUMENTO DESCRIPCIÓN MARCA CÓDIGO UNSPSC CANT. ACORDEÓN DIATONICO ADG. DIMENSIONES - TAMAÑO: 31A X 32L. PESO: 7.5, COLOR: AZUL, TONALIDADES: ADG, NÚMERO 60131200 ACORDEON ADG 1 DE BOTONES: 31, NÚMERO DE FILAS: 3 FILAS, NÚMERO DE NOTAS: 8 NOTAS, ACCESORIOS: ESTUCHE + CORREA. ACORDEÓN ROJO BESAS. DIMENSIONES - TAMAÑO: 31A X 32L. PESO: 7,5. TONALIDAD: BESAS. NÚMERO DE BOTONES: ACORDEON BESAS 2 31. NÚMERO DE FILAS: 3 FILAS. 60131200 NÚMERO DE NOTAS: 8 NOTAS. ACCESORIOS: ESTUCHE + CORREA. ARPA LLANERA CON ESTUCHE. DE 32 CUERDAS EN CEDRO O 60131300 ARPA LLANERA 15 PINO, LLAVE AFINADORA Y FORRO INCLUIDOS. ATRILES DE BANDEJA TIPO DIRECTOR. 25" A 49" (65 CM A 124 CM), DESDE EL BORDE DE LA MESA HASTA EL PISO. BASE SOLDADA DE ACERO DE CALIBRE 12 QUE BRINDA DURABILIDAD. EL ACOPLAMIENTO DE LA BASE NO SE TAMBALEA. EL DELGADO POSTE DE 1" (2,5 60131500 ATRIL 111 CM) HACE QUE RESULTE SENCILLO TRANSPORTAR DOS ATRILES CON UNA SOLA MANO. LA MESA DE ALUMINIO DE 13½" X 20" (34 CM X 51 CM) POSEE UN SOPORTE DE ALUMINIO DE UNA SOLA PIEZA. EL AJUSTE DE ALTURA POR FRICCIÓN SENCILLA SOPORTA 9 LB (4 KG). BAJO ELECTRICO. CUERPO DE ALISO. MÁSTIL DE ARCE ATORNILLADO. DIAPASÓN DE SONOKELIN. LONGITUD DE LA ESCALA: 864CM (ESCALA BAJO ELECTRICO 8 LARGA). 24 TRASTES. ANCHO 60131300 DE LA CEJILLA: 40MM. 1 PASTILLA DE BOBINA DIVIDIDA. 1 PASTILLA DE BOBINA SIMPLE. HERRAJES DE CROMO. BANDOLA ANDINA ELECTRO ACUSTICA. TAPA ARMÓNICA EN PINO ABETO ALEMÁN O CEDRO ROJO CANADÁ MIL HILOS; ARO Y FONDO EN CEDRO PUERTO ASÍS MACIZO; MÁSTIL EN CEDRO PUERTO ASÍS REFORZADO CON BANDOLA ANDINA 15 NAZARENO; CLAVIJERO DE 60131300 PRECISIÓN; DIAPASÓN EN PALO DE ROSA CON ENTRASTADO ALTACA ( PLATEADO) DEBIDAMENTE ENCORDADO Y CON ESTUCHE DURO EN LONA. -

John Griffiths, Vihuela Vihuela Hordinaria & Guitarra Española

John Griffiths, vihuela 7:30 pm, Thursday April 14, 2016 St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church Miami, Florida Society for Seventeenth-Century Music Annual Conference Vihuela hordinaria & guitarra española th th 16 and 17 -century music for vihuela and guitar So old, so new Fantasía 8 Luis Milán Fantasía 16 (c.1500–c.1561) Fantasía 11 Counterpoint to die for Fantasía sobre un pleni de contrapunto Enríquez de Valderrábano Soneto en el primer grado (c.1500–c.1557) Fantasía del author Miguel de Fuenllana Duo de Fuenllana (c.1500–1579) Strumming my pain Jácaras Antonio de Santa Cruz (1561–1632) Jácaras Santiago de Murcia (1673–1739) Villanos Francisco Guerau Folías (1649–c.1720) Folías Gaspar Sanz (1640–1710) Winds of change Tres diferencias sobre la pavana Valderrábano Diferencias sobre folias Anon. Diferencias sobre zarabanda John Griffiths is a researcher of Renaissance music and culture, especially solo instrumental music from Spain and Italy. His research encompasses broad music-historical studies of renaissance culture that include pedagogy, organology, music printing, music in urban society, as well as more traditional areas of musical style analysis and criticism, although he is best known for his work on the Spanish vihuela and its music. He has doctoral degrees from Monash and Melbourne universities and currently is Professor of Music and Head of the Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music at Monash University, as well as honorary professor at the University of Melbourne (Languages and Linguistics), and an associate at the Centre d’Etudes Supérieures de la Renaissance in Tours. He has published extensively and has collaborated in music reference works including The New Grove, MGG and the Diccionario de la música española e hispanoamericana. -

FAKING a BAROQUE GUITAR Jay Reynolds Freeman Summary: ======I Converted a Baritone Ukulele Into an Ersatz Baroque Guitar

FAKING A BAROQUE GUITAR Jay Reynolds Freeman Summary: ======= I converted a baritone ukulele into an ersatz Baroque guitar. It was a simple modification, and the result is a charming little guitar. Background: ========== I don't know how an electric guitar player like me got interested in Baroque music, but after noodling with "Canarios" on a Stratocaster for a few months, I began wondering what it sounded like on the guitars Gaspar Sanz played. Recordings of Baroque guitar music abound, but the musicians commonly use contemporary classical guitars, which are almost as far removed from the Baroque guitar as is my Strat. Several luthiers build replica Baroque guitars, but they are very expensive, and I couldn't find one locally. I am only a very amateur luthier. With lots of work and dogged stubbornness, I might be able to scratch-build a playable Baroque guitar replica, but I wasn't sure that my level of interest warranted an elaborate project, so I dithered. Then I met someone on the web who had actually heard a Baroque guitar; he said it sounded more like a modern ukulele than a modern classical guitar, though with a softer, richer sound. That started me thinking about a more modest project -- converting a modern instrument into a Baroque guitar. I had gotten a Baroque guitar plan from the Guild of American Luthiers. Its light construction, small body, and simple bracing were indeed ukulele-like. A small classical guitar might have made a better starting point, but it is hard to add tuners to a slotted headstock, and I find classical necks awkwardly broad, so a large ukulele was more promising. -

MUSIC 158 Proceeds with Techniques and Compositions of Intermediate Level for Classical Guitar

COURSE OUTLINE : MUSIC 158 D Credit – Degree Applicable COURSE ID 001203 AUGUST 2020 COURSE DISCIPLINE : MUSIC COURSE NUMBER : 158 COURSE TITLE (FULL) : Classical Guitar III COURSE TITLE (SHORT) : Classical Guitar III CATALOG DESCRIPTION MUSIC 158 proceeds with techniques and compositions of intermediate level for classical guitar. Included for study are selected pieces from the Renaissance, Baroque, Classic and Romantic eras, as well as solo arrangements of familiar tunes. Knowledge of the entire fingerboard is further enhanced by the practice of two and three octave scales. Basic skills for transcribing music written for keyboard are introduced. CATALOG NOTES Note: This class requires the student to have a full-size guitar in playable condition. Total Lecture Units: 0.00 Total Laboratory Units: 1.00 Total Course Units: 1.00 Total Lecture Hours: 0.00 Total Laboratory Hours: 54.00 Total Laboratory Hours To Be Arranged: 0.00 Total Contact Hours: 54.00 Total Out-of-Class Hours: 0.00 Prerequisite: MUSIC 157 or equivalent. GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLLEGE --FOR COMPLETE OUTLINE OF RECORD SEE GCC WEBCMS DATABASE-- Page 1 of 4 COURSE OUTLINE : MUSIC 158 D Credit – Degree Applicable COURSE ID 001203 AUGUST 2020 ENTRY STANDARDS Subject Number Title Description Include 1 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II Analyze and perform music of greater Yes contrapuntal and rhythmic complexity; 2 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II observe and demonstrate variations in Yes volume; 3 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II incorporate proper techniques for slurs and Yes grace notes into music as required; 4 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II develop the ability to produce natural and Yes artificial harmonics; 5 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II extend familiarity with the fret board by Yes practicing scales in several positions; 6 MUSIC 157 Classical Guitar II construct basic triads in major and minor Yes keys and apply them to the comprehension of fretboard harmony. -

“Apoyando” and “Tirando” Related to Its Harmonic Components and Autocorrelation Function

Buenos Aires – 5 to 9 September, 2016 Acoustics for the 21st Century… PROCEEDINGS of the 22nd International Congress on Acoustics Music Perception: Paper ICA2016-227 Subjective preference of classical guitar strokes “apoyando” and “tirando” related to its harmonic components and autocorrelation function Joaquin Garcia(a), Shin-ichi Sato(b), Florent Masson(c) (a)Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina, [email protected] (b)Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina, [email protected] (c)Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina, [email protected] Abstract Tone production of classical guitar performance is an essential part for musicians to transmit their sentimental and interpretative intentions. This work investigates subjective preferences of two common plucking techniques used by guitar players, apoyando (rest) and tirando (free) strokes. Six excerpts of classical guitar music with different tempos and range of frequency were performed using the two techniques and were recorded for the subjective tests. Two groups of subjects, guitar players and people who do not play guitar, were investigated to see if both groups evaluate the guitar timbre in different way or not. AB test was conducted with 50 persons for each group asking which technique is preferred and have more sound quality. Then the harmonic components and autocorrelation function (ACF) of each stroke were analysed to relate with the characteristics of the music program (tempo and frequency range) and subjective preferences. The effective duration of ACF is defined with the taue (τe) parameter. Results of the subjective test showed that harmonic content did not define preferences, but higher taue values of the ACF were correlated with a higher sound guitar quality. -

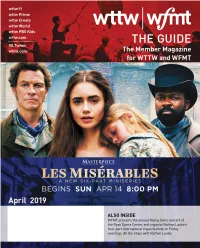

Wwciguide April 2019.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center This month, we are excited to bring you a sweeping new adaptation of Victor Hugo’s 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 classic novel Les Misérables. This new six-part series, featuring an all-star cast including Dominic West, David Oyelowo, and recent Oscar winner Olivia Colman, tells the story of fugitive Jean Valjean, his relentless pursuer Inspector Javert, and other colorful characters Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 in turbulent 19th century France. We hope you’ll join us on Sunday nights for this epic Member and Viewer Services drama, and explore extra content on our website including episode recaps and fact vs. (773) 509-1111 x 6 fiction. If spring is a time of renewal, that is also certainly true of some of WTTW’s offerings Websites wttw.com in April, including eagerly awaited new seasons of three very different British detective wfmt.com series – Father Brown, Death in Paradise, and Unforgotten – and Mexico: One Plate at a Time, Jamestown, and Islands Without Cars. On wttw.com, as American Masters features Publisher newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer, we profile Chicago winners of the journalism and Anne Gleason arts award that bears his name, and highlight some extraordinary African American Art Director Tom Peth entrepreneurs in Chicago. WTTW Contributors WFMT will present the annual Rising Stars concert of the Ryan Opera Center, and Julia Maish Dan Soles organist Nathan Laube’s four-part international organ festival on Friday evenings, All the WFMT Contributors Stops with Nathan Laube. -

Play Days 2011 Approach and Start Off-Topic

Volume 26, No. 6 April 2011 The Making of On Cold Mountain— The Journey to On Cold Mountain Songs on Poems of Gary Snyder There is a natural way to write a narrative and an artful way. The natural way, according to the rhetoricians, is to Roy Whelden The editor of this newsletter, Peter Brodigan, has asked me to write about the recently released recording On Cold Mountain—Songs on Poems of Gary Snyder (Innova Records 795). The CD contains four new song cycles written by Fred Frith, W.A. Mathieu, Robert Morris, and me. The performers are the contralto Karen Clark and the Galax Quartet: David Wilson and Elizabeth Blumenstock, violins; Roy Whelden, viola da gamba; David Morris, ’cello. Peter felt that I, as a composer and the viola da gamba player in the Galax Quartet, might have something interesting to say concerning the making of the album. In the account which follows, I try to write to the interests in particular of the viol playing community. start at the beginning and press toward the end, The release party for the new CD takes place on April 25 chronologically. The artful way is to start at a mid-point from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Musical Offering Cafe on 2430 and allow the story to unfold. Both ways are of equal Bancroft Avenue in Berkeley. A few selections from the validity. album will be performed. Profits from sales at this event, The problem with the natural way of telling this particular as well as from items ordered online the same day story, the making of On Cold Mountain, is that the at www.galaxquartet.org, will be donated to the Pacifica beginning is nebulous. -

Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth Centuries and Twentieth Centuries Paul Sparks

Performance Practice Review Volume 10 Article 7 Number 1 Spring Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth Centuries and Twentieth Centuries Paul Sparks Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Sparks, Paul (1997) "Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth Centuries and Twentieth Centuries," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 10: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199710.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol10/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guitar Performance in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Paul Sparks By 1800 guitars with six single strings (tuned EAdgbe') had become the norm. The rosette gave way to an open sound hole, while the neck was lengthened and fitted with a raised fingerboard extending to the sound hole. Nineteen fixed metal frets eventually became standard, the top note sounding b". The bridge was raised, the body enlarged, and fan-strutting introduced beneath the table to support higher tension strings. Treble strings were made of gut (superseded by more durable nylon after World War 11), bass strings from metal wound on silk (or, more recently, nylon floss). Tablature became obsolete, guitar music being universally written in the treble clef, sounding an octave lower than written. By the 1820s makers such as Louis Panormo of London were replacing wooden tuning pegs with machine heads for more precise tuning, and creating the prototype of the modem classical guitar (a design perfected in mid-century by Antonio Torres). -

Guitar Cross Reference Updated 02/22/08 Includes: Acoustic, Bass, Classical, and Electric Guitars

Gator Cases Guitar Cross Reference Updated 02/22/08 Includes: Acoustic, Bass, Classical, and Electric Guitars Use Ctrl-F to search by Manufacturer or Model Number Manufacturer Model Type Fits (1) Fits (2) Fits (3) Fits (4) Fits (5) Alvarez AC60S Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez Artist Series AD60K Dao Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez Artist Series AD60S Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez Artist Series AD70S Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez Artist Series AD80SSB Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez CYM95 Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez MC90 Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez RC10 Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez RD20S Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez RD8 Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez RD9 Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Aria PE-STD Series Electric Guitar GL-LPS GC-LPS GPE-LPS G-Tour LPS GW-LPS Cordoba 32E Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Cordoba 32EF Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Cordoba 45FM Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic