View Four Siblings About Their Childhoods, They Would Each Describe a Completely Different Family.” Your Story, Then, Is Yours and No One Else’S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaker Affirmations 1

SSttuuddeenntt NNootteebbooookk ffir r A m e a k t A Course i a of Study for o u n Q Young Friends Suggested for Grades 6 - 9 Developed by: First Friends Meeting 3030 Kessler Boulevard East Drive Indianapolis, IN 46220-2913 317.255.2485 [email protected] wwQw.indyfriends.org QQuuaakkeerr AAffffiirrmmaattiioonn:: AA CCoouurrssee ooff SSttuuddyy ffoorr YYoouunngg FFrriieennddss Course Conception and Development: QRuth Ann Hadley Tippin - Pastor, First Friends Meeting Beth Henricks - Christian Education & Family Ministry Director Writer & Editor: Vicki Wertz Consultants: Deb Hejl, Jon Tippin Pre- and Post-Course Assessment: Barbara Blackford Quaker Affirmation Class Committee: Ellie Arle Heather Arle David Blackford Amanda Cordray SCuagrogl eDsonteahdu efor Jim Kartholl GraJedde Ksa y5 - 9 First Friends Meeting 3030 Kessler Boulevard East Drive Indianapolis, IN 46220-2913 317.255.2485 [email protected] www.indyfriends.org ©2015 December 15, 2015 Dear Friend, We are thrilled with your interest in the Quaker Affirmation program. Indianapolis First Friends Meeting embarked on this journey over three years ago. We moved from a hope and dream of a program such as this to a reality with a completed period of study when eleven of our youth were affirmed by our Meeting in June 2015. This ten-month program of study and experience was created for our young people to help them explore their spirituality, discover their identity as Quakers and to inform them of Quaker history, faith and practice. While Quakers do not confirm creeds or statements made for them at baptism, etc, we felt it important that young people be informed and af - firmed in their understanding of who they are as Friends. -

Rich Mullins Best Lyrics

Rich mullins best lyrics click here to download Song Lyrics The lyrics to each of Rich's songs are presented here. Rich Mullins · A Few Good World as Best as I Remember It, Volume One · Step by Step. 13 explanations, 9 meanings for Rich Mullins lyrics including Step By Step, Awesome God, Ready For The Storm at www.doorway.ru A Few Good Men. www.doorway.ru is the best in class, definitive online destination for the The following is a list of Rich Mullins' top 10 songs of all time: Favorite Lyric: “Well, it took the hand of God Almighty to part the waters of the sea. Rich Mullins lyrics: 'The Love Of God', 'The Color Green', 'The Maker Of Noses' etc. Jacob And 2 Women (The World As Best As I Remember · Jesus Jordan. Find and save ideas about Rich mullins on Pinterest. Rich Mullins - Contemporary Christian artist best known for his hits .. What great lyrics to sing! Find this. Lyrics to 'A Few Good Men' by Rich Mullins. Show me someone who makes a difference / Show me someone who's brave when he needs to be / I just need to. Awesome God by Rich Mullins w/ lyrics:D Our God is an Awesome God the name alone means it's gonna. Rich Mullins song lyrics collection. Browse lyrics and 61 Rich Mullins albums. The World as Best as I Remember It, Volume 1 Lyrics Rich Mullins. A Liturgy, A Legacy & A Ragamuffin Band [] · The World as Best as I Remember It, Vol. 2 [] · Pictures In The Sky []. -

Sunday, Monday & Tuesday December 15, 16 & 17, 2019 At

“AN ADVENT/CHRISTMAS SPIRITUALITY ALL YEAR: A. Our response to our human nature being MY WILL WITH GOD’S” embraced by God who takes on our flesh PRESENTER: FR. MIKE JOLY B. Openness to the love that God so wishes to (WWW.FATHERMIKEJOLEY.COM - [email protected]) pour into our lives (This is MIRACLE - God entering into ADVENT MISSION human nature) IMMACULATE CONCEPTION CATHOLIC CHURCH, MELBOURNE BEACH, FLORIDA VIII. Chains shall He break for the slave is our SUNDAY, MONDAY & TUESDAY brother; DECEMBER 15, 16 & 17, 2019 AT 7:00 PM And in His name all oppression shall cease - Sweet hymns of joy in grateful chorus raise we; Let all Evening Two within us praise His holy name - Christ is the Lord; that ever, ever praise we His power and glory ever Continuing the Incarnation of Christ Despite Our more proclaim - His power and glory ever more Human Frailty proclaim. The Angelus: IX. The Greatest Miracle: The Incarnation (Fulton Sheen) The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary….And she “God requires a man” conceived of the Holy Spirit A. Who is Jesus? Hail Mary, full of grace….. B. Mary’s “yes” gives God permission Behold the handmaid of the Lord….Be it done to me C. Uniting our human nature to the Divine according to thy word. Nature of God Hail Mary, full of grace….. 1. No identity crisis And the Word was made flesh….And dwells among us. 2. Flexibility 3. Visibility Recap Evening One I. Christmas: Journey of a superman or a savior? A. Qualities and effects of a superman B. -

January-17-Sale-Sheets.Pdf

January Releases Aaron Keyes - Through It All Description Aaron’s heart is to restore the Word of God to the foundation of corporate worship, which led to Aaron and his wife Megan launching their worship school, 10,000 Fathers. Since then, many worship pastors from around the world have come through their home, gone through their training, and become part of their broader family. Aaron has recently been to the UK to launch the first 10,000 Fathers School in England, as well as host and lead worship at the Mission Worship conference, where he has partnered and lead worship over the last 10 years. Aaron is one of the great songwriters of our generation, writing songs such as ‘Sovereign Over Us’, ‘Song Of Moses’, and co-writing with some of the most well-known worship leaders of today. His new worship album Through It All is where resounding lyrical depth meets refreshing musical height as Spirit greets Truth in psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs. The album features co-writes with Bethel’s Brian Johnson, Jesus Culture’s Chris Quilala, Stuart Townend, Pete James, & Housefires’ Pat Barrett. Songs from the album are already starting to be sung in Chuches across the UK and the world, particularly ‘King Forevermore’ the co-write with Pete James. Track Listing: Also available (RECORDED LIVE) 1. Crying Holy (feat. Zach Smith) 2. The Valley Aaron Keyes - In The Living Room Barcode: 0000768523025 3. Faithful Through It All Price: £7.99 4. King Forevermore (God the Uncreated One) (feat. David Walker) 5. The Swan 6. And Can It Be 7. -

The Apostles' Creed in Modern English (From the Book of Common Prayer)

The Apostles' Creed in Modern English (From the Book of Common Prayer) I believe in God, the Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth. I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried; On the third day he rose again; he ascended into heaven, he is seated at the right hand of the Father, and he will come to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic* Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting. Amen. *The word “Catholic” in the Apostles’ Creed does NOT refer to the Roman Catholic church but to Christ’s true Church (Big “C”) in the universal sense of all believers. ---------------------------------------------------- Why Is This Creed Important? While not actually written by the apostles (that we know of), the Apostles Creed is the oldest known creed of the Church. It provides a synopsis of faithful, Christian belief. It dates back to 140 AD (at least) and provides a type of format for future creeds. If you memorize a creed, this is a good one to memorize. Rich Mullins wrote a song called “Creed” that is essentially the Apostles Creed set to music. It was later popularized by Third Day. The song is a good way to memorize. However, both Mullins and Third day use a latter version of the Apostles Creed which includes the phrase “he descended into Hell” in reference to Jesus death and burial. -

Michael W. Smith Worship Mp3, Flac, Wma

Michael W. Smith Worship mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Worship Country: US Released: 2001 Style: Soft Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1771 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1578 mb WMA version RAR size: 1927 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 693 Other Formats: AA MP4 VQF MOD AAC FLAC DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Forever 1 5:49 Written-By – Chris Tomlin The Heart Of Worship 2 6:15 Written-By – Matt Redman Draw Me Close 3 4:14 Written-By – Kelly Carpenter Turn Your Eyes Upon Jesus 4 3:12 Arranged By – Michael W. Smith Open The Eyes Of My Heart 5 5:21 Written-By – Paul Baloche Above All 6 4:23 Words By, Music By – Lenny LeBlanc, Paul Baloche Breathe 7 6:56 Written-By – Marie Barnett Let It Rain 8 5:39 Written-By – Michael Farron Agnus Dei 9 6:40 Written-By – Michael W. Smith Awesome God 10 4:40 Written-By – Rich Mullins More Love, More Power 11 5:10 Written-By – Jude Del Hierro Bonus Tracks Purified (Studio Version) Contractor – Carl GorodetzkyOrchestra – The Nashville String MachinePercussion 12 4:32 [Additional] – Ken Lewis Programmed By – Jim Daneker, Michael W. SmithWritten- By – Deborah D. Smith, Michael W. Smith Above All (Studio Version) 13 Guitar [Additional] – Jerry McPhersonProgrammed By – Kent HooperWords By, 4:36 Music By [Uncredited] – Lenny LeBlanc, Paul Baloche Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Reunion Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Reunion Records, Inc. Manufactured By – Provident Music Distribution, Inc. Distributed By – Provident Music Distribution, Inc. Published By – SixSteps Music Published By – Kingsway's Thankyou Music Published By – Mercy/Vineyard Publishing Published By – Word Music, Inc. -

The Echo: September 26, 1997

Inside This Issue, Rosh Hashanah 2 Rich Mullins tribute 4 The Webmaster 5 Album review 7 Concert/album release schedule 7 TAYLOR UNIVERSITY STUDENT NEW* September 26, 1997 Volume 84, Issue 4 Upland, Indiana Students overload the VAX using the VAX the first three weeks p.m. Therefore, during those JESSICA BARNES of this school year, "one-half have hours, it takes longer to log onto Campus Editor been freshmen at any given time." the system, longer to read and re According to Mahan, the VAX, ply to the e-mail and printing speed Taylor's VAX system cannot commonly known as FIGMNT, is suffering. Severe slowdowns keep up with this year's freshman serves Taylor in five ways. It is have caused users to be thrown off class. According to Bob Hodge, the main handler of e-mail for all the system, sometimes without vice president for planning and in traffic to and from the Internet; warning. formation resources, without a and, it serves e-mail directly for all Mahan reported that four major computer upgrade or a decrease in students and faculty for both cam changes have been made to coun e-mail usage by the class of 2001, puses. teract these problems. The news the VAX cannot return to normal The VAX also supports Netscape update jobs no longer run after 12 speed. e-mail for various faculty users. p.m. The number of logins is lim "I am not suprised that access to Third, the VAX is the main com ited to between 80 and 90. -

Faith Through Lawyering: Finding and Doing What Is Mine to Do

FAITH THROUGH LAWYERING: FINDING AND DOING WHAT IS MINE TO DO Randy Lee* I. INTRODUCTION When one sets out to write on Christian lawyering, he undertakes an enormous task and not simply because he attempts to discuss seri- ously "the lawyer joke to top them all!"1 Perhaps the greater challenge is that there are almost as many ways to address the issue of lawyering as 2 a Christian as there are traditions and sub-traditions of Christians. Within the Catholic tradition, for example, Professor Teresa Stanton Collett recently approached the question of how the Christian works as a lawyer as one that must recognize the wholeness and interconnectedness of each person in many roles.3 Robert J. Muise approached the same . Associate Professor of Law, Widener University School of Law - Harrisburg Cam- pus. The author would like to thank Paula Heider and especially Shannon Whitson for technical support and encouragement, and Brenda Lee for sharing callings with me. The author would also like to thank Ann Britton, Craig Callaghan, John Dernbach, James Diehm, Anthony Fejfar, David Gregory, Mary Kate Kearney, Samuel Levine, Michael Pipa, Jeff Powell, Loren Prescott, Bob Rodes, Teresa Stanton Collett, and Tom Shaffer for their comments and encouragement; and Joe Allegretti for writing the book that inspired this project. As this article was being written, God called Mother Teresa and Rich Mullins to end their sojourn on Earth and join Him in Heaven. May this work reflect more of them than of me and more of God than of them. I JOSEPH G. ALLEGRETTI, THE LAWYER'S CALLING: CHRISTIAN FAITH AND LEGAL PRACTICE 1 (1996). -

Jesus Is for Losers by Shane Claiborne

Copyright © 2008 Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University Jesus Is for Losers BY SHANE CLAIBORNE In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus warns, “Do not judge, so that you may not be judged.” Folks are hungry for a Christianity that mirrors Jesus, not the judgmentalism that has done more to repel than to woo people towards God’s grace. few months back as I was getting ready to speak to a group of folks, the pastor approached me beforehand to point out that a couple of A gay men were sitting on the front row, holding hands. He felt the need to point it out. “Are you going to say something about that, about homosexuality?” he whispered. I laughed, and said, “I’m not sure what you have in mind. I could begin by saying I praise God that they felt welcome enough to come into this place, that I am glad they are here.” That is not what he had in mind. I wondered to myself, following his logic, if he would then want me to ask everyone who had been divorced and remarried to stand up so we could give them a little firm rebuke. In fact, maybe we should just station folks at the doors of the church like bouncers in clubs—sort of a sin patrol. They could ask people as they enter the building: “Have you been prideful or greedy this week?” And we could bounce all the nasty sinners out of the service. We’d be left with much smaller crowds to deal with. -

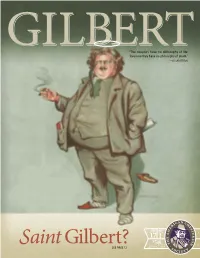

Saintgilbert?

“The skeptics have no philosophy of life because they have no philosophy of death.” —G.K. chesTERTON VOL NO 17 1 $550 SEPT/OCT 2013 . Saint Gilbert?SEE PAGE 12 . rton te So es l h u C t i Order the American e o n h T nd E nd d e 32 s Chesterton Society u 32 l c E a t g io in n th , E y co ver Annual Conference Audio nomics & E QTY. Dale Ahlquist, President of the American QTY. Carl Hasler, Professor of Philosophy, QTY. Kerry MacArthur, Professor of English, Chesterton Society Collin College University of St. Thomas “The Three Es” (Includes “Chesterton and Wendell “How G.K. Chesterton Dale’s exciting announce- Berry: Economy of Scale Invented Postmodern ment about GKC’s Cause) and the Human Factor” Literature” QTY. Chuck Chalberg as G.K. Chesterton QTY. Joseph Pearce, Writer-in-Residence and QTY. WIlliam Fahey, President of Thomas Professor of Humanities at Thomas More More College of the Liberal Arts Eugenics and Other Evils College; Co-Editor of St. Austin Review “Beyond an Outline: The “Chesterton and The Hobbit” QTY. James Woodruff, Teacher of Forgotten Political Writings Mathematics, Worcester Academy of Belloc and Chesterton” QTY. Kevin O’Brien’ s Theatre of the Word “Chesterton & Macaulay: two Incorporated presents histories, two QTY. Aaron Friar (converted to Eastern Orthodoxy as a result of reading a book Englands” “Socrates Meets Jesus” By Peter Kreeft called Orthodoxy) QTY. Pasquale Accardo, Author and Professor “Chesterton and of Pediatric Medicine QTY. Peter Kreeft, Author and Professor of Eastern Orthodoxy” “Shakespeare’s Most Philosophy, Boston College Catholic Play” The Philosophy of DVD bundle: $120.00 G.K. -

Calvary Memorial Church

Welcome to Contact Us Church office- 308-436-5554 CalvaryCalvary MemorialMemorial ChurchChurch Office hours Mon-Thu 9 a.m.—12:00 p.m. Established In Memory of Calvary, Prayer Line - 308-630-4130 CalvaryCalvary MemorialMemorial ChurchChurch Proclaiming the Message of Calvary Pastor Gary Hashley - 308-641-3805 October 21, 2018 We’re honored that you chose to attend Calvary. Senior Pastor If you’re visiting us for the first or second time, Pastor Joe Patterson - 832-418-5396 Youth Pastor please bring your “Connect Card” to Guest Services Shirley Swanson - 308-631-6030 to let us know how we may best serve you Office Manager and for a special welcome gift. Meagan Stobel - 308-631-2046 We hope to see you again! Pastoral Assistant Rick and Marie Parker - 308-765-1781 Nursery and Children’s Church are available both services Children's Ministry Directors Our staff will text you if your child needs assistance Zen and LouAnn Voorhies - 308-765-5293 Senior Ministry Directors This Week Andy Stobel 308-641-2125 Life Group Director Sunday Mindy Joekel - 631-1708 Bri Kihlthau - 641-0575 8:00 a.m. VIP Prayer Women’s Ministry Directors 8:30 a.m. Worship/Children’s Church “Blessed to Bless” 9:45 a.m. Children’s Sunday School www.calvarygering.org (website) Pastor Gary Hashley 9:45 a.m. Adam & Hosanna Lancaster (LifeGroup) Sermons are online under the “media” tab 10:45 a.m. Worship/Children’s Church Church activity calendar 6:00 p.m. David Sedaca Presentation “Give” tab for online donations 6:30 p.m. -

Worship Series Planner | Week 3

WORSHIP SERIES PLANNER | WEEK 3 Theme | Hospitality Offered to a Stranger is Hospitality Offered to Christ Scripture | Matthew 25:35-40 [ when I was hungry… ] Sermon Title | Radical Hospitality | Entertaining Strangers = Entertaining Jesus Desired Outcome | Congregants will seek to help and build relationships with those they don’t know Sermon Building Key Points • Just how far would you go to help a stranger? • Tell personal story of when a stranger helped you • How radical is our hospitality to those we don’t know? • When we respond to someone in need we are responding to Christ • Entertaining a stranger is equivalent to entertaining Jesus • Christian hospitality is the active desire to invite, welcome, receive and care for those who are strangers so that they find a spiritual home and discover an unending life in Jesus Christ • Who are the strangers we encounter but overlook? • When we build a relationship with someone they cease to be a stranger • Call to action: Learn the name of someone you don’t know and begin to listen to his or her story. See this person as not only loved by God, but loved by God through you. Seek to demonstrate genuine love to those who are not part of your faith community. Prayer for the Week Dear God, help me to recognize you in each person I serve. Amen. Daily Readings for Week 3 Monday • Hebrews 13:2-4 Tuesday • Genesis 18:1-21 Wednesday • Leviticus 19:34 Thursday • Matthew 10:40-42 Friday • Deuteronomy 10:17-21 Saturday • Matthew 18:1-5 [ Continued on page 2 ] THE MISSOURI ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED