Counterfactual Considerations on Rommel's First Offensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medical Conditions in the Western Desert and Tobruk

CHAPTER 1 1 MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN THE WESTERN DESERT AND TOBRU K ON S I D E R A T I O N of the medical and surgical conditions encountered C by Australian forces in the campaign of 1940-1941 in the Wester n Desert and during the siege of Tobruk embraces the various diseases me t and the nature of surgical work performed . In addition it must includ e some assessment of the general health of the men, which does not mean merely the absence of demonstrable disease . Matters relating to organisa- tion are more appropriately dealt with in a later chapter in which the lessons of the experiences in the Middle East are examined . As told in Chapter 7, the forward surgical work was done in a main dressing statio n during the battles of Bardia and Tobruk . It is admitted that a serious difficulty of this arrangement was that men had to be held for some tim e in the M.D.S., which put a brake on the movements of the field ambulance , especially as only the most severely wounded men were operated on i n the M.D.S. as a rule, the others being sent to a casualty clearing statio n at least 150 miles away . Dispersal of the tents multiplied the work of the staff considerably. SURGICAL CONDITIONS IN THE DESER T Though battle casualties were not numerous, the value of being able to deal with varied types of wounds was apparent . In the Bardia and Tobruk actions abdominal wounds were few. Major J. -

Brevity, Skorpion & Battleaxe

DESERT WAR PART THREE: BREVITY, SKORPION & BATTLEAXE OPERATION BREVITY MAY 15 – 16 1941 Operation Sonnenblume had seen Rommel rapidly drive the distracted and over-stretched British and Commonwealth forces in Cyrenaica back across the Egyptian border. Although the battlefront now lay in the border area, the port city of Tobruk - 100 miles inside Libya - had resisted the Axis advance, and its substantial Australian and British garrison of around 27,000 troops constituted a significant threat to Rommel's lengthy supply chain. He therefore committed his main strength to besieging the city, leaving the front line only thinly held. Conceived by the Commander-in-Chief of the British Middle East Command, General Archibald Wavell, Operation Brevity was a limited Allied offensive conducted in mid-May 1941. Brevity was intended to be a rapid blow against weak Axis front-line forces in the Sollum - Capuzzo - Bardia area of the border between Egypt and Libya. Operation Brevity's main objectives were to gain territory from which to launch a further planned offensive toward the besieged Tobruk, and the depletion of German and Italian forces in the region. With limited battle-ready units to draw on in the wake of Rommel's recent successes, on May 15 Brigadier William Gott, with the 22nd Guards Brigade and elements of the 7th Armoured Division attacked in three columns. The Royal Air Force allocated all available fighters and a small force of bombers to the operation. The strategically important Halfaya Pass was taken against stiff Italian opposition. Reaching the top of the Halfaya Pass, the 22nd Guards Brigade came under heavy fire from an Italian Bersaglieri (Marksmen) infantry company, supported by anti-tank guns, under the command of Colonel Ugo Montemurro. -

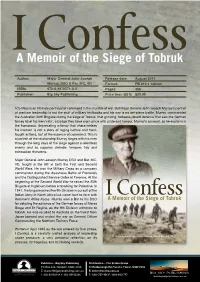

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

(June 1941) and the Development of the British Tactical Air Doctrine

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies A Stepping Stone to Success: Operation Battleaxe (June 1941) and the Development of the British Tactical Air Doctrine Mike Bechthold On 16 February 1943 a meeting was held in Tripoli attended by senior American and British officers to discuss the various lessons learned during the Libyan campaign. The focus of the meeting was a presentation by General Bernard Montgomery. This "gospel according to Montgomery," as it was referred to by Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, set out very clearly Monty's beliefs on how air power should be used to support the army.1 Among the tenets Montgomery articulated was his conviction of the importance of air power: "Any officer who aspires to hold high command in war must understand clearly certain principles regarding the use of air power." Montgomery also believed that flexibility was the greatest asset of air power. This allowed it to be applied as a "battle-winning factor of the first importance." As well, he fully endorsed the air force view of centralized control: "Nothing could be more fatal to successful results than to dissipate the air resource into small packets placed under the control of army formation commanders, with each packet working on its own plan. The soldier must not expect, or wish, to exercise direct command over air striking forces." Montgomery concluded his discussion by stating that it was of prime importance for the army and air 1 Arthur Tedder, With Prejudice: The war memoirs of Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Lord Tedder (London: Cassell, 1966), p. -

![Infantry Division (1941-43)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3816/infantry-division-1941-43-583816.webp)

Infantry Division (1941-43)]

7 February 2017 [6 (70) INFANTRY DIVISION (1941-43)] th 6 Infantry Division (1) Headquarters, 6th Infantry Division & Employment Platoon 14th Infantry Brigade (2) Headquarters, 14th Infantry Brigade & Signal Section 1st Bn. The Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment 2nd Bn. The York and Lancaster Regiment 2nd Bn. The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) 16th Infantry Brigade (3) Headquarters, 16th Infantry Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Bn. The Leicestershire Regiment 2nd Bn. The Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey) 1st Bn. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Princess Louise’s) (4) 23rd Infantry Brigade (5) Headquarters, 23rd Infantry Brigade & Signal Section 4th (Westmorland) Bn. The Border Regiment 1st Bn. The Durham Light Infantry (6) Czechoslovak Infantry Battalion No 11 East (7) Divisional Troops 60th (North Midland) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (8) (H.Q., 237th (Lincoln) & 238th (Grimsby) Field Batteries, Royal Artillery) 2nd Field Company, Royal Engineers 12th Field Company, Royal Engineers 54th Field Company, Royal Engineers 219th (1st London) Field Park Company, Royal Engineers 6th Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals © www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 7 February 2017 [6 (70) INFANTRY DIVISION (1941-43)] Headquarters, 6th Infantry Divisional Royal Army Service Corps (9) 61st Company, Royal Army Service Corps 145th Company, Royal Army Service Corps 419th Company, Royal Army Service Corps Headquarters, 6th Infantry Divisional Royal Army Medical Corps (10) 173rd Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps 189th -

Operation Brevity Axis Forces May 15, 1941

Operation Brevity Axis Forces May 15, 1941 Kampfgruppe von Herff ( everything on this page ) II/5th severely Panzer under- Regiment strength These two battalions after recent were stationed at x 1 x 2 x 1 x 1 campaign Bardia and were the mobile reaction force Italian for any trouble along from the the border. I/61st Trento Motorized division Infantry Battalion x 9 x 2 x 1 x 1 x 13 15th This reinforced company held the top of Halfaya Motorcycle pass for the early part of Battalion the battle before finally (1 company) x 3 x 1 x 2 x 3 being overrun. These two recon 3rd battalions from the Recon two Panzer Divisions Battalion were stationed be- x 1 x 1 x 1 x 3 x 3 x 1 x 2 hind the border and ready to respond to any enemy threats as needed. 33rd Recon 33rd was ordered to coun- Recon terattack late in the Battalion first day but called it off when 7 Matildas x 1 x 1 x 1 x 3 x 3 x 2 x 4 were spotted. Possibly stationed represents near the top of two 105 Halfaya Pass. howitzers x 1 x 1 x 2 x 2 x 1 x 1 15th Stationed at Motorcycle Bir Hafid Battalion (-) x 5 x 1 x 1 x 1 x 8 Kampfgruppe von Herff mainly acted as mobile reserve to back up the Italians who were defending the border. When the battle started, nearly all By Greg Moore these forces were put on the move to respond to the British. -

![7 Armoured Division (1941-42)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4788/7-armoured-division-1941-42-1304788.webp)

7 Armoured Division (1941-42)]

3 September 2020 [7 ARMOURED DIVISION (1941-42)] th 7 Armoured Division (1) Headquarters, 7th Armoured Division 4th Armoured Brigade (2) Headquarters, 4th Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 4th Royal Tank Regiment (3) 5th Royal Tank Regiment (3) 7th Royal Tank Regiment (4) 7th Armoured Brigade (5) Headquarters, 7th Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Royal Tank Regiment 7th Support Group (6) Headquarters, 7th Support Group & Signal Section 1st Bn. The King’s Royal Rifle Corps 2nd Bn. The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) 3rd Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery 4th Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery 1st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery Divisional Troops 11th Hussars (Prince Albert’s Own) (7) 4th Field Squadron, Royal Engineers (8) 143rd Field Park Squadron, Royal Engineers (8) 7th Armoured Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 3 September 2020 [7 ARMOURED DIVISION (1941-42)] NOTES: 1. This was a regular army division stationed in Egypt. It had been formed as the Mobile Division in September 1938, as a result of the raised tension caused by the Munich Crisis. Initially called the ‘Matruh Mobile Force’, it was founded by Major General P. C. S. HOBART. This is the Order of Battle for the division on 15 May 1941. This was the date of the start of Operation Brevity, the operation to reach Tobruk The division was under command of Headquarters, British Troops in Egypt until 16 May 1941. On that date, it came under command of Headquarters, Western Desert Force (W.D.F.). It remained under command of W.D.F. -

World War Ii (1939–1945) 56 57

OXFORD BIG IDEAS HISTORY 10: AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM 2 WORLD WAR II (1939–1945) 56 57 depth study World War II In this depth study, students will investigate wartime experiences through a study of World War II. is includes coverage of the causes, events, outcome and broad impact of the con ict as a part of global history, as well as the nature and extent of Australia’s involvement in the con ict. is depth study MUST be completed by all students. 2.0 World War II (1939–1945) The explosion of the USS Shaw during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941 SAMPLE OXFORD BIG IDEAS HISTORY 10: AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM 2 WORLD WAR II (1939–1945) 58 59 Australian Curriculum focus HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE AND UNDERSTANDING • An overview of the causes and course of World War II • An examination of significant events of World War II, including the Holocaust and use of the atomic bomb depth study • The experiences of Australians during World War II (such as Prisoners of War (POWs), the Battle of Britain, World War II Kokoda, the Fall of Singapore) (1939–1945) • The impact of World War II, with a particular emphasis on the Australian home front, including the changing roles of women and use of wartime government World War II was one of the de ning events of the 20th century. e war was controls (conscription, manpower controls, rationing played out all across Europe, the Paci c, the Middle East, Africa and Asia. and censorship) e war even brie y reached North America and mainland Australia. -

The Greatest Military Reversal of South African Arms: the Fall of Tobruk 1942, an Avoidable Blunder Or an Inevitable Disaster?

THE GREATEST MILITARY REVERSAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN ARMS: THE FALL OF TOBRUK 1942, AN AVOIDABLE BLUNDER OR AN INEVITABLE DISASTER? David Katz1 Abstract The surrender of Tobruk 70 years ago was a major catastrophe for the Allied war effort, considerably weakening their military position in North Africa, as well as causing political embarrassment to the leaders of South Africa and the United Kingdom. This article re-examines the circumstances surrounding and leading to the surrender of Tobruk in June 1942, in what amounted to the largest reversal of arms suffered by South Africa in its military history. By making use of primary documents and secondary sources as evidence, the article seeks a better understanding of the events that surrounded this tragedy. A brief background is given in the form of a chronological synopsis of the battles and manoeuvres leading up to the investment of Tobruk, followed by a detailed account of the offensive launched on 20 June 1942 by the Germans on the hapless defenders. The sudden and unexpected surrender of the garrison is examined and an explanation for the rapid collapse offered, as well as considering what may have transpired had the garrison been better prepared and led. Keywords: South Africa; HB Klopper; Union War Histories; Freeborn; Gazala; Eighth Army; 1st South African Division; Court of Enquiry; North Africa. Sleutelwoorde: Suid-Afrika; HB Klopper; Uniale oorlogsgeskiedenis; Vrygebore; Gazala; Agste Landmag; Eerste Suid-Afrikaanse Bataljon; Hof van Ondersoek; Noord-Afrika. 1. INTRODUCTION This year marks the 70th anniversary of the fall of Tobruk, the largest reversal of arms suffered by South Africa in its military history. -

Book a Facilitated Program for 2011 and We Will Provide a Much Deeper

EDUCATION SERVICES 2 011 Tobruk Ray Ewers and George Browning, 1954-56 AWM ART41035 Book a facilitated program for 2011 and we will provide a much deeper learning experience. RelAWM31948.004 Tobruk 1941 – A Gallant Information For Teachers and Tenacious Defence Book a facilitated program for your school group; a program will provide a much deeper learning experience. New programs, aligned to the Australian The whole empire is watching your steadfast and Curriculum for History, are now available. spirited defence … with gratitude and admiration. Prime Minister Winston Churchill The Australian War Memorial provides a wide range of REL07652 Teacher’s checklist educational programs aligned with the new Australian Curriculum for History. These programs are designed to Log on to www.awm.gov.au/education and read about the Memorial’s curriculum-based programs and choose The fate of the war in North Africa hung on the possession protect it ran in a rough semicircle across the desert suit your classroom and curriculum needs. which program best suits the needs of your students. of a small harbour town in the far corner of the Libyan desert from coast to coast, and consisted of dozens of concrete- When you visit the Memorial, and book a facilitated – Tobruk. It was vital for the Allies’ defence of Egypt and the sided strong-points protected by barbed-wire fences and program, students gain a much deeper learning Book your visit online and record your booking Suez Canal to hold the town with its harbour, as this forced anti-tank ditches. experience. Our trained educators draw on personal reference number. -

Crusader: Battle for Tobruk

CRUSADER: BATTLE FOR TOBRUK ERRATA: The U.K. Support Fire counter mix should include one additional "+6" Support Fire chit. EXCLUSIVE RULES 10.0 INTRODUCTION 10.1 First Player 11.0 REINFORCEMENTS 11.1 Quantity of Reinforcements 11.2 When Reinforcements Arrive 11.3 Where Reinforcements Arrive 11.4 Reinforcements and Combat 12.0 LINES OF COMMUNICATION 13.0 ENEMY ZONES OF CONTROL 14.0 MINEFIELDS 14.1 Friendly Minefields 14.2 Enemy Minefields 14.3 German Engineers 14.4 Fortified Boxes 15.0 SIDI REZEGH AIRFIELD 16.0 ESCARPMENT HEXSIDES 17.0 VICTORY CONDITIONS 17.1 Sudden Battle Conclusion 18.0 SCENARIOS 19.0 GAME NOTES 10.0 INTRODUCTION Crusader is a simulation of the battle in Libya between forces of the British Commonwealth and those of Germany and Italy (known as Operation Crusader, named after the British Crusader tank). The British were attempting to relieve Tobruk from the ongoing German siege. 10.1 FIRST PLAYER The British player is the first player throughout the game (see 3.0). 11.0 REINFORCEMENTS The British player receives five specific reinforcement units during the game (see 11.1). The German player receives no reinforcements. 11.1 QUANTITY OF REINFORCEMENTS GAME TURN TWO Unit Type: Hexes: 1-1-15 1523, 1524 3-4-9 1525, 1625 GAME TURN SIX 3-3-9 3921 11.2 REINFORCEMENTS ARRIVE At the end of the movement phase (reinforcements may not move during the turn they arrive). Mobile units that arrive at the end of the movement phase may not move during the mobile movement phase. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00471-9 - Britain’s Two World Wars Against Germany: Myth, Memory and the Distortions of Hindsight Brian Bond Index More information INDEX Advanced Air Striking Force 29, 147 Beyond the Fringe 11 Aldington, Richard 4 Blackadder Goes Forth 21–22, 48–49, All Our Yesterdays newsreels 10 127 Allies, WWII strategy 145, 146–163 Blitzkrieg 70, 147 Amiens blood transfusion 71 Battle of 64, 140–141 Blunden, Edmund 4, 126–143 Gestapo prison bombing 107 Bomber Command Anzio, combat conditions 80–81 defence of British Isles 36 appeasement 28, 170 strategic bombing of Germany area bombing 112–114 100–124 Armistice, WWI 95, 166, 167–168 accuracy 106–107, 112–114 Army–Air co-operation, failure of 147 arguments in favour of 102 Arnhem 160–161 Berlin 105 casualties 161 casualties 105, 115–116, 117, 123: Arras, Second Battle of friendly fire 108–109 improvements in warfare 132–133 contribution to victory 123 tunnels 132–133 criticism of 102–103, 119–122 artillery, WWI, modernisation 55, 129, Dam Busters raid 106–107 131, 132–133, 136–137 Dresden 114–119 Asquith, Herbert Henry, German Hamburg 105 invasion of Belgium 27 Lancaster bombers 104, 110, 115 Attlee, Clement 165 Mosquito fighter-bomber 106–107, Australian Corps, WWI 139–140, 142 110, 115 oil targets 111–112, 114, 116 B-17 bombers 115 Operation Overlord 106, 107–109 battlefield conditions P51 Mustang fighter-bomber WWI 4–5 109–110 Western Front 4–5 railways 112 WWII 4 Ruhr 104–105, 112 Belgium, threat from Germany 1914 27 Sir Arthur Harris: bombing priorities Berlin,