The State University of New York #Realcollege Survey Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suny Cuad Suny Cuad

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK SUNY CUAD COUNCIL FOR UNIVERSITY ADVANCEMENT 2013 Annual Awards STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK for Excellence SUNY CUAD COUNCIL FOR UNIVERSITY ADVANCEMENT SUNYCUAD EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCE I SYRACUSE, N.Y. I JUNE 13 - 15, 2013 2013 Annual Awards for Excellence Congratulations to all of this year’s winners! The quality of your work confirms that we are all part of not only the largest, but the finest, comprehensive university system in the United States. Welcome! The Mission The SUNY Council for University Advancement (SUNYCUAD) is proud to present once again of SUNYCUAD its annual Awards for Excellence program. The Awards for Excellence recognizes the outstanding work of SUNY colleges and universities and SUNYCUAD members, and every year, the results SUNYCUAD promotes understanding get even better. and support of the State University and provides professional development The process began early this year when the and networking opportunities for call for entries was sent to our more than 800 advancement professionals in the areas members. In the spring, the host coordinators, of public relations, alumni relations, who coordinate the judging for each of the publications, electronic communications, 20 categories, graciously stepped forward to development, government relations and support the effort. The host coordinators each assembled expert judges in their respective marketing. categories to evaluate the entries and make the The organization encourages members very difficult decision of choosing winners. and their SUNY institutions to carry out their responsibilities in an ethical and The winning entries reflect programs and professional manner by: projects that have achieved exceptional results through solid planning, well-conceived goals • Creating a climate of sharing best and objectives and resourceful and effective practices through a comprehensive solutions. -

Office of the President Office of the Vice

2012 – 2013 SUNY SULLIVAN CATALOG Part 6 - PROFESSIONAL STAFF OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT Dr. William J. Murabito Stephanie Smart Interim President Administrative Associate to the Human Resources Ph.D. University of Illinois Director M.S. SUNY Albany A.A.S. SUNY Sullivan B.S. State University College at Buffalo Public Safety Kathleen Ambrosino David Seigerman Executive Administrative Associate to the President Director of Public Safety/Peace Officer and the Board of Trustees B.S. Empire State College B.S. Empire State College A.A.S. SUNY Sullivan Keith Molinari Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Professional Assistant Director of Public Safety/Peace Officer Services 2011 Kristi Gilmore Human Resources Keyboard Specialist Sharon K. Sand A.A.S. SUNY Sullivan Human Resources Director M.A. SUNY New Paltz B.A. SUNY New Paltz OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT FOR ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS Dr. Robert E. Schultz James Goldfarb Vice President for Academic and Student Affairs Director of Student Life and Housing Ph.D. Columbia University Assistant Professor M.S. Ed. Baruch College M.A. Fairleigh Dickinson University M.A. Rutgers University B.F.A. Rhode Island School of Design B.A. Rutgers College Registration Services Iman Elginbehi Laura Sampson, Ed.D. Assistant Vice President for Academic and Student Coordinator of Registration Services Affairs Ed.D. University of Oregon M.B.A. SUNY New Paltz M.S. University of Oregon B.S. SUNY New Paltz B.S. Springfield College A.S. SUNY Ulster Linda Matrafailo Anne Gattus Secretary Senior Administrative Associate to the Vice President for Academic and Student Affairs Robert Psarudakis B.A. -

Conference 2016 Full Program

NEW YORK STATE MATHEMATICS ASSOCIATION OF TWO-YEAR COLLEGES 49th Annual Conference April 8 - 10 2016 Kingston, New York NYSMATYC Executive Board 2015-16 President Junior Member at Large Larry Danforth Hatesh Radia Jefferson Community College Corning Community College President-Elect Curriculum Committee Chair Josh Hammond Chris Kemp Jefferson Community College Genesee Community College Past-President Legislative Committee Chair Russ Penner Jane-Marie Wright Mohawk Valley Community College Suffolk Community College-Ammerman Campus Secretary Scholarship Committee Chair Michael Riedinger Patty Owens Nassau Community College Onondaga Community College Treasurer Professional Development Committee Chair Richard Moscatelli Brian Milleville Nassau Community College Erie Community College - South Senior Member at Large Articulation Committee Chair Heather Huntington Joe Bernat Nassau Community College Nassau Community College Additional Appointed Positions Historian Kate Danforth Corning Community College Math League Coordinator Abe Mantell Nassau Community College Web Master Ken Mead Genesee Community College www.nysmatyc.org/eboard.php Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................... - 4 - Message from the President-Elect .................................................................................................................. - 5 - Program Summary ......................................................................................................................................... -

History of NYSMATYC 1967-2017 (Pdf)

Page 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 2 Origin of NYSMATYC .............................................................................................................. 3 Membership History .............................................................................................................. 6 NYSMATYC Executive Board ................................................................................................... 7 Past Presidents .......................................................................................................... 7 Committees .......................................................................................................................... 9 Curriculum Committee ............................................................................................. 10 NYSMATYC Surveys .................................................................................................. 11 Legislative Committee.............................................................................................. 12 Scholarship Committee ............................................................................................ 13 Scholarship History .................................................................................................. 14 Webmaster.............................................................................................................. 16 NYSMATYC Conferences...................................................................................................... -

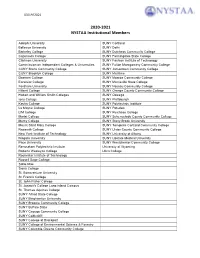

2020-2021 NYSTAA Institutional Members

03/19/2021 2020-2021 NYSTAA Institutional Members Adelphi University SUNY Cortland Bellevue University SUNY Delhi Berkeley College SUNY Dutchess Community College Cazenovia College SUNY Farmingdale State College Clarkson University SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology Commission on Independent Colleges & Universities SUNY Fulton Montgomery Community College CUNY Bronx Community College SUNY Jamestown Community College CUNY Brooklyn College SUNY Maritime Daemen College SUNY Monroe Community College Excelsior College SUNY Morrisville State College Fordham University SUNY Nassau Community College Hilbert College SUNY Orange County Community College Hobart and William Smith Colleges SUNY Oswego Iona College SUNY Plattsburgh Keuka College SUNY Polytechnic Institute Le Moyne College SUNY Potsdam LIM College SUNY Purchase College Marist College SUNY Schenectady County Community College Mercy College SUNY Stony Brook University Mount Saint Mary College SUNY Tompkins Cortland Community College Nazareth College SUNY Ulster County Community College New York Institute of Technology SUNY University at Albany Niagara University SUNY Upstate Medical University Pace University SUNY Westchester Community College Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute University of Wyoming Roberts Wesleyan College Utica College Rochester Institute of Technology Russell Sage College Sallie Mae Siena College St. Bonaventure University St. Francis College St. John Fisher College St. Joseph's College Long Island Campus St. Thomas Aquinas College SUNY Alfred State College SUNY Binghamton University SUNY Broome Community College SUNY Buffalo State SUNY Cayuga Community College SUNY Cobleskill SUNY College at Brockport SUNY College of Environmental Science & Forestry SUNY Columbia-Greene Community College . -

2019-2020 NYSTAA Institutional Members

12/10/2019 2019-2020 NYSTAA Institutional Members Adelphi University SUNY Albany Bellevue University SUNY Binghamton Canisius College SUNY Brockport Cazenovia College SUNY Broome Concordia College – NY SUNY Buffalo State College Cornell University SUNY Cayuga CC CUNY Bronx Community College SUNY Cobleskill CUNY Hostos Community College SUNY Columbia Greene CUNY Queensborough Community College SUNY Cortland Daemen College SUNY Delhi D’Youville College SUNY Dutchess Community College Excelsior College SUNY Empire State College Five Towns College SUNY Farmingdale State College Fordham University SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology Hilbert College SUNY Fredonia Houghton College SUNY Fulton Montgomery Community College Iona College SUNY Genesee Community College Keuka College SUNY Hudson Valley Community College LeMoyne College SUNY Jamestown LIM College SUNY Mohawk Valley Community College Manhattan College SUNY Monroe Community College Manhattanville College SUNY Morrisville State College Marist College SUNY Nassau Community College Marymount Manhattan College SUNY New Paltz MCLA SUNY Oneonta Mercy College SUNY Onondaga Community College Mount Saint Mary College SUNY Orange Nazareth College SUNY Oswego New York Institute of Technology SUNY Plattsburgh Niagara University SUNY Polytechnic Institute Pace University SUNY Purchase Quinnipiac University SUNY Schenectady County Community College Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute SUNY Stony Brook University Roberts Wesleyan College SUNY Suffolk County Community College Russel Sage College SUNY Tompkins Cortland Community College Siena College SUNY Ulster St. Bonaventure SUNY Westchester Community College St. Francis College St. John Fisher College 12/10/2019 St. Joseph’s College St. Thomas Aquinas College The College of St. Rose University of Rochester Utica College Wells College . -

Administrative Officers and Support Staff

2017 – 2018 SUNY SULLIVAN CATALOG Part 6 - PROFESSIONAL STAFF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS AND SUPPORT STAFF President ........................................................................................................................................ John Quaintance Executive Assistant to the President and Administrative Associate to the Board of Trustees ............................................................... Linda Roffel Vice President for Academic and Student Affairs .......................................................................... Dr. Keith Pomakoy Senior Administrative Associate to the Vice President for Academic and Student Affairs ..................................................................................... Charissa Gonzalez Dean of Community Outreach ............................................................................................ Cindy Bennedum Kashan Administrative Associate to the Dean of Community Outreach ................................................ Wanda Toney Associate Vice President for Planning, Human Resources, and Facilities ............................. Dr. Stephen M. Mitchell Administrative Associate to the Assoc. Vice President of Planning, Human Resources, and Facilities ............................................................................................. Wanda Toney Assistant Director of Human Resources .............................................................................. Stephanie Smart ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS Director of the Department of Learning -

1:30 PM Laguardia Community College NY College Fair Thursday 6-Oct-16 12:00 PM - 2:00 PM SUNY Adirondack (Queensbury) Queensbury NY College Fair

Day Date Time Location City State Event Type Thursday 6-Oct-16 11:00 AM - 1:30 PM LaGuardia Community College NY College Fair Thursday 6-Oct-16 12:00 PM - 2:00 PM SUNY Adirondack (Queensbury) Queensbury NY College Fair Monday 10-Oct-16 10:30 AM - 1:30 PM Columbia-Greene Community College Hudson NY Advisor in Residence Tuesday 11-Oct-16 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM Herkimer County Community College Herkimer NY College Fair Tuesday 11-Oct-16 10:30 AM - 1:30 PM SUNY Ulster Stone Ridge NY Advisor in Residence Tuesday 11-Oct-16 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM Mohawk Valley Community College Utica NY College Fair Wednesday 12-Oct-16 10:00 AM - 12:00 PM Holyoke Community College Holyoke MA College Fair Thursday 13-Oct-16 11:00 AM - 2:00 PM SUNY Adirondack (Queensbury) Queensbury NY Advisor in Residence Monday 17-Oct-16 10:30 AM - 1:30 PM Hudson Valley Community College Troy NY Advisor in Residence Monday 17-Oct-16 12:40 PM - 1:50 PM SUNY Adirondack (Queensbury) Queensbury NY Business Panel Tuesday 18-Oct-16 10:30 AM - 1:30 PM Fulton-Montgomery Community College Johnstown NY Advisor in Residence Tuesday 18-Oct-16 10:30 AM - 1:30 PM Asnuntuck Community College Enfield CT College Fair Wednesday 19-Oct-16 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM Schenectady County Community College Schenectady NY Advisor in Residence Wednesday 19-Oct-16 7:00 PM - 9:00 PM SUNY Rockland Suffern NY College Fair Thursday 20-Oct-16 10:00 AM - 1:00 PM Kingsborough Community College Brooklyn NY College Fair Thursday 20-Oct-16 10:30 AM - 1:00 PM SUNY Adirondack (Wilton) Wilton NY College Fair Monday 24-Oct-16 9:30 -

Web Appendices

State University of New York System #RealCollege Survey: WEB APPENDICES 1 Appendix A. Participating Colleges Two-Year Colleges Alfred State College Cayuga Community College Dutchess Community College Fashion Institute of Technology Finger Lakes Community College Hudson Valley Community College Jamestown Community College Mohawk Valley Community College Monroe Community College Nassau Community College Onondaga Community College SUNY Adirondack SUNY Corning Community College SUNY Delhi SUNY Erie Community College SUNY Morrisville SUNY Orange Westchester Community College Four-Year Colleges and Universities SUNY Cobleskill SUNY College Old Westbury SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry SUNY Cortland SUNY Empire State College SUNY Fredonia SUNY Maritime College SUNY New Paltz SUNY Oneonta SUNY Oswego SUNY Polytechnic Institute SUNY Potsdam SUNY Upstate Medical University Stony Brook University The College at Brockport 2 Appendix B. Survey Methodology SURVEY ELIGIBILITY AND PARTICIPATING COLLEGES Together with administrators, the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice fielded this survey to all participating institutions. The State University of New York (SUNY) system agreed to administer an online survey in the fall and offer 150 $100 prizes to their students across all participating campuses at SUNY in order to boost response rates. Institution staff sent a series of invitations and follow-up reminders to all enrolled students encouraging them to participate. The Hope Center provided the email invitation language as well as hosted the survey as shown below. Upon opening the survey, students were presented with a consent form in compliance with Institutional Review Board standards. To actually take the survey, the student must have clicked continue as a record of consent and completed a minimum of the first page of the survey. -

NYSTAA Member Institutions (Updated January 10, 2019)

NYSTAA Member Institutions (Updated January 10, 2019) Adelphi University St. John Fisher College Bellevue University St. Joseph's College - Long Island Canisius College SUNY Adirondack Cazenovia College SUNY Albany Clarkson University SUNY Binghamton Commission on Independent Colleges and Universities SUNY Brockport Concordia College - NY SUNY Broome Community College CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College SUNY Buffalo State College CUNY Bronx Community College SUNY Cobleskill CUNY John Jay College SUNY Columbia Greene Community College CUNY LaGuardia Community College SUNY Cortland CUNY Queensborough Community College SUNY Delhi Daemen College SUNY Dutchess Community College D'Youville College SUNY Empire State College Excelsior College SUNY Erie Community College Fordham University SUNY Farmingdale State College Hartwick College SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology Hofstra University SUNY Finger Lakes Community College Houghton College SUNY Fredonia Iona College SUNY Fulton Montgomery Community College Ithaca College SUNY Genesee Community College Keuka College SUNY Hudson Valley Community College LIM College SUNY Jamestown Community College MCLA SUNY Jefferson Manhattan College SUNY Mohawk Valley Community College Marist College SUNY Monroe Community College Marymount Manhattan College SUNY Morrisville State College Mercy College SUNY Nassau Community College Moravian College SUNY New Paltz Mount Saint Mary College SUNY Niagara County Community College Nazareth College SUNY Old Westbury New York Institute of Technology SUNY Oneonta -

As of May 20, 2019

As of May 20, 2019 Adelphi University SUNY Adirondack Bellevue University SUNY Albany Canisius College SUNY Binghamton Cazenovia College SUNY Brockport Clarkson University SUNY Broome Community College Commission on Independent Colleges & SUNY Buffalo State College Universities Concordia College – NY SUNY Cobleskill CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College SUNY Columbia Greene CUNY Bronx Community College SUNY Corning CUNY Hostos Community College SUNY Cortland CUNY John Jay College SUNY Delhi CUNY LaGuardia Community College SUNY Dutchess Community College CUNY Queensborough Community College SUNY Empire State College Daemen College SUNY Erie Community College D’Youville College SUNY Farmingdale State College Excelsior College SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology Fordham University SUNY Finger Lakes Community College Hartwick College SUNY Fredonia Hilbert College SUNY Fulton Montgomery Community College Hofstra University SUNY Genesee Community College Houghton College SUNY Herkimer Iona College SUNY Hudson Valley Community College Ithaca College SUNY Jamestown Keuka College SUNY Jefferson LIM College SUNY Mohawk Valley Community College Manhattan College SUNY Monroe Community College Manhattanville College SUNY Morrisville State College Maria College SUNY Nassau Community College Marist College SUNY New Paltz Marymount Manhattan College SUNY Niagara County Community College MCLA SUNY Old Westbury Mercy College SUNY Oneonta Moravian College SUNY Onondaga Community College Mount Saint Mary College SUNY Orange Nazareth College SUNY Oswego New York Institute of Technology SUNY Plattsburgh Niagara University SUNY Polytechnic Institute NYC DOE Office of Post-Secondary Readiness SUNY Potsdam Pace University SUNY Purchase Quinnipiac University SUNY Rockland Community College Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute SUNY Schenectady County Community College RIT SUNY Stony Brook University Roberts Wesleyan College SUNY Suffolk County Community College Siena College SUNY Sullivan St. -

Institute 1 Agenda Institute #1: Benchmarking, Capacity, and Transformational Change

Institute 1 Agenda Institute #1: Benchmarking, capacity, and transformational change Institute #1 Objectives: 1. Provide clarity about pathway project goals, expectations of colleges, and supports for participants. 2. Establish a common definition for guided pathways and their essential elements. 3. Reinforce change leadership strategies for implementing pathways at scale. 4. Explore how guided pathways reforms can build on and help to integrate student success strategies already in place in the institution. 5. Build a "case statement" for pathways tailored to individual institution context and current status that will help build urgency and increase momentum for transformational change. 6. Facilitate the development of institutional draft action plans that delineate next steps in taking pathways reforms to scale at the institution, specifically incorporating strategies for professional development and campus engagement. 7. Begin to build an engaged learning network among pathways project colleges. Thursday, October 3, 2019 9:00 – 10:00 am Institute Check-in Just Outside Stage 14 9:15 – 9:45 am Coaching Meetings Cohort Coaches to meet with Cohort II Team Facilitators Room 1136 Discussion topics: Institute 1 agenda, team strategy session goals, review upcoming post work assignments Alumni Coach to meet with Alumni Representatives Stage 14 Discussion topics: Institute 1 agenda and team strategy session goals 9:50 am Hudson Valley Community College team photo (in main event room) 9:55 am Nassau Community College team photo (in main event room) 10:00 – 10:30 am Welcome Dr. Robert K. Nye, President, Finger Lakes Community College Johanna Duncan-Poitier, Sr. Vice Chancellor, Community Colleges and the Education Pipeline, State University of New York Stage 14 Related Institute Objective: 1, 7 1 | P a g e Institute 1 Agenda 10:30 – 12:00 pm Opening Keynote: Guided Pathways: Making the Case Dr.