Jurisprudential Revolution Unlocking Human Potential in Lawrence and Grutter Wilson R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Imagining United States History Through Contemporary Asian American and Latina/O Literature

LATINASIAN NATION: RE-IMAGINING UNITED STATES HISTORY THROUGH CONTEMPORARY ASIAN AMERICAN AND LATINA/O LITERATURE Susan Bramley Thananopavarn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: María DeGuzmán Jennifer Ho Minrose Gwin Laura Halperin Ruth Salvaggio © 2015 Susan Bramley Thananopavarn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Susan Thananopavarn: LatinAsian Nation: Re-imagining United States History through Contemporary Asian American and Latina/o Literature (Under the direction of Jennifer Ho and María DeGuzmán) Asian American and Latina/o populations in the United States are often considered marginal to discourses of United States history and nationhood. From laws like the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to the extensive, racially targeted immigration rhetoric of the twenty-first century, dominant discourses in the United States have legally and rhetorically defined Asian and Latina/o Americans as alien to the imagined nation. However, these groups have histories within the United States that stretch back more than four hundred years and complicate foundational narratives like the immigrant “melting pot,” the black/white binary, and American exceptionalism. This project examines how Asian American and Latina/o literary narratives can rewrite official histories and situate American history within a global context. The literary texts that I examine – including works by Carlos Bulosan, Américo Paredes, Luis Valdez, Mitsuye Yamada, Susan Choi, Achy Obejas, Karen Tei Yamashita, Cristina García, and Siu Kam Wen – create a “LatinAsian” view of the Americas that highlights and challenges suppressed aspects of United States history. -

The Christine Camp Archives: Waldenside

THE CHRISTINE CAMP ARCHIVES: WALDENSIDE FINDING TOOL Denise D. Monbarren Summer 1998 CHRISTINE CAMP ARCHIVES: WALDENSIDE ADDRESSES BY THE KENNEDY ADMINISTRATION: Kennedy, John F. “This Country is Moving . and It Must Not Stop.” Text of the speech he was scheduled to deliver at the Texas Welcome Dinner at the Municipal Auditorium in Austin, Texas, Nov. 22, 1963. Kennedy, John F. “We Are . the Watchmen on the Walls of Freedom.” Text of the speech he was scheduled to deliver in the Trade Mart in Dallas, Texas, Nov. 22, 1963. AUDIOTAPES: [A History of the Camp Family Farm.] BOOKS: Note: Books are catalogued and shelved in Special Collections LC Collection. Bernstein, Carl and Woodward, Bob. All the President’s Men. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974. Dust jacket. Gift to Camp from Bob Woodward. Bishop, Jim. A Day in the Life of President Kennedy. New York: Random House, 1964. Dust jacket. Inscribed to Camp by author. Beschloss, Michael R. Kennedy and Roosevelt: The Uneasy Alliance. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1980. First ed. Dust jacket. Bradlee, Benjamin C. Conversations with Kennedy. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., Inc., 1975. Dust jacket. Dixon, George. Leaning on a Column. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1961. First ed. Inscribed to Camp by author. Donovan, Robert J. PT 109: John F. Kennedy in World War II. New York: McGraw-HIll Book Co., 1961. Inscribed to Camp by the author. John Fitzgerald Kennedy. As We Remember Him. Ed. by Joan Meyers. Philadelphia: Courage Books, 1965. Dust jacket. The Joint Appearances of Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard M. -

FIGURE 1: March 1942 Photograph by Dorothea Lange of the Sign in Front of the Shuttered Wanto Co. Grocery Store, Owned by the Ja

FIGURE 1: March 1942 photograph by Dorothea Lange of the sign in front of the shuttered Wanto Co. grocery store, owned by the Japanese American Masuda family in the previ- ously thriving Japantown neighborhood of Oakland, California. The Oakland-born owner, Tatsuro Masuda, a graduate of the University of California, had the sign painted the day after Japan’s bombing of the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor. He closed the store follow- ing President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which ordered persons of Japanese de- scent to evacuate from designated “military areas” on the West Coast. On August 7, 1942, Masuda and his family, who had moved inland to Fresno, were incarcerated; they were con- fined at the Gila River War Relocation Center in Arizona until August 1944. Masuda’s “I am an American” sign conveys the way that global conflict manifested itself at the most quotidian levels in the twentieth-century United States, prompting some immigrant and immigrant-descended families to assert national belonging in unchosen relationship to emerging forms of racialized, geopolitical enmity. National Archives and Records Adminis- tration, RG 210, Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority, 210-G-C519. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/123/2/393/4958230 by Divinity Library, Vanderbilt University user on 06 April 2018 Review Essay The Geopolitics of Mobility: Immigration Policy and American Global Power in the Long Twentieth Century PAUL A. KRAMER SOMETHING ABOUT THE FALL OF WESTERN EUROPE to the Nazis in mid-1940 convinced many Americans that their state was not protecting them sufficiently from immigrants. -

United States Policy Toward Israel: the Politics, Sociology, Economics & Strategy of Commitment

United States Policy Toward Israel: The Politics, Sociology, Economics & Strategy of Commitment Submitted for Ph.D. in International Relations at the London School of Economics & Political Science Elizabeth Stephens 2003 UMI Number: U613349 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613349 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 C ontents Page Abstract 4-5 Chapter 1 The Special Relationship 6 -3 6 Chapter 2 Framing American Foreign Policy 37 - 86 Chapter 3 American Political Culture & Foreign Policy 87 - 131 Chapter 4 The Johnson Administration and U.S. Policy Toward Israel 132 - 185 Chapter 5 Nixon, Kissinger and U.S. Policy Toward Israel 186 - 249 Chapter 6 Reagan, the Neo-Conservatives and Israel 250 - 307 Chapter 7 Bush, the Gulf War and Israel 308 - 343 Chapter 8 Framing American Foreign Policy in the New World Order 344 - 375 Conclusions 376 - 379 Appendix A U.N. Security Council Resolution 242 380-382 Appendix B The Rogers Plan 383 Appendix C United Nations Security Council Resolution 338 384 Appendix D The Camp David Accords 385 -391 Bibliography 392-412 1 Hr£TS £ F 82.1 / Acknowledgements The writing of this thesis would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of my supervisor Geoffrey Stem, Senior Lecturer at the London School of Economics. -

In the Land of Mirrors Front.Qxd 10/11/1999 9:41 AM Page Ii Front.Qxd 10/11/1999 9:41 AM Page Iii

front.qxd 10/11/1999 9:41 AM Page i In the Land of Mirrors front.qxd 10/11/1999 9:41 AM Page ii front.qxd 10/11/1999 9:41 AM Page iii In the Land of Mirrors Cuban Exile Politics in the United States María de los Angeles Torres Ann Arbor front.qxd 10/11/1999 9:41 AM Page iv Copyright © by the University of Michigan 1999 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2002 2001 2000 1999 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Torres, María de los Angeles. In the land of mirrors : Cuban exile politics in the United States / María de los Angeles Torres. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-472-11021-7 (alk. paper) 1. Cuban Americans—Politics and government. 2. Cubans—United States—Politics and government. I. Title. E184.C97T67 1999 324'.089'687294073—dc21 99-36965 CIP front.qxd 10/11/1999 9:41 AM Page v In memory of Lourdes Casal, who built the bridge, and Eliseo Diego, who opened the door. For my daughters, Alejandra María and Paola Camila Piers-Torres —may they relish their multiple heritage. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 / Oct. 16 1573 I Said That We Would

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 / Oct. 16 I said that we would put in place health care sure your kids can go to college, make sure that reform to make sure that insurance companies you are getting a good-paying job, making sure can’t jerk you around and if you don’t have that Medicare and Social Security will be there health insurance, that you’d have a chance to for you? get affordable insurance, and I have. Ms. Crowley. Mr. President, thank you. I committed that I would rein in the excess- Governor. es of Wall Street, and we passed the toughest Wall Street reforms since the 1930s. National Economy/Unemployment Rate We’ve created 5 million jobs—gone from 800,000 jobs a month being lost—and we are Gov. Romney. I think you know better. I making progress. We saved an auto industry think you know that these last 4 years haven’t that was on the brink of collapse. been so good as the President just described and that you don’t feel like you’re confident Now, does that mean you’re not struggling? that the next 4 years are going to be much bet- Absolutely not. A lot of us are. And that’s why ter either. I can tell you that if you were to the plan that I’ve put forward for manufactur- elect President Obama, you know what you’re ing and education and reducing our deficit in a going to get. You’re going to get a repeat of the sensible way, using the savings from ending last 4 years. -

Cuban Missile Crisis

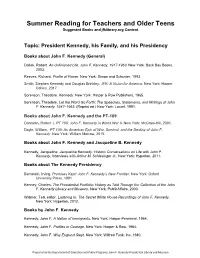

Summer Reading for Teachers and Older Teens Suggested Books and jfklibrary.org Content Topic: President Kennedy, his Family, and his Presidency Books about John F. Kennedy (General) Dallek, Robert. An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963. New York: Back Bay Books, 2003. Reeves, Richard. Profile of Power. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993. Smith, Stephen Kennedy and Douglas Brinkley. JFK: A Vision for America. New York: Harper Collins, 2017. Sorenson, Theodore. Kennedy. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1965. Sorenson, Theodore. Let the Word Go Forth: The Speeches, Statements, and Writings of John F. Kennedy, 1947–1963. (Reprint ed.) New York: Laurel, 1991. Books about John F. Kennedy and the PT-109 Donovan, Robert J. PT 109: John F. Kennedy in World War II. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001. Doyle, William. PT 109: An American Epic of War, Survival, and the Destiny of John F. Kennedy .New York: William Morrow, 2015. Books about John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline B. Kennedy Kennedy, Jacqueline. Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy, Interviews with Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., New York: Hyperion, 2011. Books about The Kennedy Presidency Bernstein, Irving. Promises Kept: John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. Kenney, Charles. The Presidential Portfolio: History as Told Through the Collection of the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum. New York: PublicAffairs, 2000. Widmer, Ted, editor. Listening In: The Secret White House Recordings of John F. Kennedy. New York: Hyperion, 2012. Books by John F. Kennedy Kennedy, John F. A Nation of Immigrants. New York: Harper Perennial, 1964. -

Using Multicultural Young Adult Literature in the Classroom

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 418 422 CS 216 312 AUTHOR Brown, Jean E., Ed.; Stephens, Elaine C., Ed. TITLE United in Diversity: Using Multicultural Young Adult Literature in the Classroom. Classroom Practices in Teaching English, Volume 29. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5571-5 ISSN ISSN-0550-5755 PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 236p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 55715-3050: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Class Activities; *Diversity (Student); *English Instruction; Instructional Effectiveness; Language Arts; *Literature Appreciation; *Multicultural Education; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Multicultural Literature; Response to Literature ABSTRACT Addressing the complexity of the question of multicultural literature in the classroom, this anthology of 27 articles includes: contemplations by seven award-winning writers of young adult (YA) literature on the subject of diversity; a resource section that describes over 200 literary works and lists 50 reference tools to help teachers stay current on multicultural YA literature; and practical ideas from 16 educators who provide strategies proven to work in literature and language arts classes and across the curriculum. The articles and their authors are: "Island Blood" (Graham Salisbury); "Random Thoughts on the Passing Parade" (Janet Bode); "Multicultural Literature: A Story of Your Own" (Joyce Hansen); "Cultural Sensitivity" (Deb Vanasse); "Reflections" (Eve Bunting); "Helping to Improve Multicultural Understanding through Humor" (Joan Bauer); "Michael and Me (and Other Voices from Flint)" (Christopher Paul Curtis); "We Are All Phenomenal Women: Finding Female Role Models through Multicultural Poetry and Literature" (Deborah Forster-Sulzer); "Creating a Talisman: Reflecting a Culture" (Jean E. -

A Dozen Facts About Immigration

ECONOMIC FACTS | OCTOBER 2018 A Dozen Facts about Immigration Ryan Nunn, Jimmy O’Donnell, and Jay Shambaugh WWW.HAMILTONPROJECT.ORG ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank Lauren Bauer, Barry Chiswick, David Dreyer, Ethan Lewis, Giovanni Peri, and Anne Piehl for insightful feedback, as well as Patrick Liu, Jana Parsons, and Areeb Siddiqui for excellent research assistance. We would also like to thank Kristin Butcher, Anne Piehl, and the Penn Wharton Budget Model for generously sharing their data. MISSION STATEMENT The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy requires public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges of the 21st century. Our strategy calls for combining increased public investments in key growth-enhancing areas, a secure social safety net, and fiscal discipline. In that framework, the Project puts forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers — based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or doctrine — to introduce new and effective policy options into the national debate. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Consistent with the guiding principles of the Project, Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. -

Media Portrayals of Cubans and Haitians: a Comparative Study of the New York Times

MEDIA PORTRAYALS OF CUBANS AND HAITIANS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE NEW YORK TIMES By MANOUCHEKA CELESTE A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Manoucheka Celeste This is dedicated to the people who live these stories and MM&I for believing. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like thank everyone who has not only supported, but also challenged me in this process. I would like to thank my committee chair, Dr. Michael Leslie, for his guidance and great effort, and willingness to challenge students. He went to great lengths to see this project through. I would also like to thank my committee members: Dr. Marilyn Roberts and Dr. Helena K. Sarkio. Dr. Roberts was a wonderful source of knowledge and played an integral role in guiding my methods and findings. Dr. Sarkio has been supportive and engaging. Her thorough editing, and advice inside and outside of the classroom have been invaluable. I thank family for setting an example of what hard work and dedication is all about. They allowed me to disappear for the last semester to complete this project. I thank my sister, Slande, for always leading the way and little brothers, James and Alix, for being great human beings and my inspiration. Also I extend thanks to my dearest life friends and SGRho sisters Manoucheka T., Magda, Candace, Shannon, and Mona, for always supporting me and still being my friends despite my virtual disappearance during this project. -

5 Categorical Syllogisms

1 Basic Concepts 1.1 Arguments, Premises, and Conclusions Logic may be defined as the science that evaluates arguments. All of us encounter arguments in our day-to-day experience. We read them in books and newspapers, hear them on television, and formulate them when communicating with friends and associates. The aim of logic is to develop a system of methods and principles that we may use as criteria for evaluating the arguments of others and as guides in constructing arguments of our own. Among the benefits to be expected from the study of logic is an increase in confidence that we are making sense when we criticize the arguments of others and when we advance arguments of our own. An argument, as it occurs in logic, is a group of statements, one or more of which (the premises) are claimed to provide support for, or reasons to believe, one of the others (the conclusion). All arguments may be placed in one of two basic groups: those in which the premises really do support the conclusion and those in which they do not, even though they are claimed to. The former are said to be good arguments (at least to that extent), the latter bad arguments. The purpose of logic, as the science that evaluates arguments, is thus to develop methods and techniques that allow us to distinguish good arguments from bad. As is apparent from the above definition, the term ‘‘argument’’ has a very specific meaning in logic. It does not mean, for example, a mere verbal fight, as one might have with one’s parent, spouse, or friend. -

Energy of a Nation: Immigrants in America Is Designed to Be Used with Eighth Grade Students Through Adult Audiences

How to Use this Teaching Guide ISBN #: 0-929293 58-4 Energy of a Nation: Immigrants in America is designed to be used with eighth grade students through adult audiences. Each of the lessons can be taught independently or woven into existing subject areas. This teaching guide begins with a general table of contents that outlines each of the eleven lessons. A unit outline follows, which summarizes student learning goals for each of the units. Each lesson begins with a quotation, goals and learning objectives. The introduction to each lesson includes a text box, which outlines suggested time frame, materials, necessary vocabulary, subject area relevance, and connection to the Minnesota State High School Standards. Below are additional suggestions for effective use of the teaching guide. 1. Journal Writing: Journal writing is an effective assessment tool and is suggested at the end of every lesson. Students will better retain the information learned if they engage in written reflection for five minutes at the end of each class period. Journal writing promotes critical thinking skills, while allowing students to debrief emotionally to material that connects to their personal lives. It gives students a safe zone for expression. Journal writing is also an excellent assessment tool. You may wish to review the journals periodically to offer feedback and encouragement to the class. As a precursor to each lesson, the students should define the vocabulary words as homework. If student journals are incorporated, we suggest having students organize their journals into multiple sections, such as: Vocabulary, Lesson Assignments, Post-lesson Reflections, and Follow-up Questions.