Using Cognitive Neuroscience to Predict Future Dangerousness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emotional Disorders in Patients with Cerebellar Damage - Case Studies

Should be cited as: Psychiatr. Pol. 2014; 48(2): 289–297 PL ISSN 0033-2674 www.psychiatriapolska.pl Emotional disorders in patients with cerebellar damage - case studies Katarzyna Siuda 1, Adrian Andrzej Chrobak 1, Anna Starowicz-Filip2, Anna Tereszko1, Dominika Dudek 3 1Students’ Scientific Association of Adult Psychiatry, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Tutor: prof. dr hab. med. D. Dudek 2Medical Psychology Department, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Head: prof. dr hab. n. hum. J.K. Gierowski 3Department of Affective Disorders, Jagiellonian University Medical College Head: prof. dr hab. med. D. Dudek Summary Aim. Growing number of research shows the role of the cerebellum in the regulation of affect. Lesions of the cerebellum can lead to emotional disregulation, a significant part of the Cerebellar Cognitive Affective Syndrome. The aim of this article is to analyze the most recent studies concerning the cerebellar participation in emotional reactions and to present three cases: two female and one male who suffered from cerebellar damage and presented post-traumatic affective and personality change. Method. The patients’ neuropsychological examination was performed with Raven’s Progressive Matrices Test – standard version, Trial Making Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Auditory Verbal Learning Test by Łuria, Benton Visual Retention Test, Verbal Fluency Test, Stroop Interference Test, Attention and Perceptivity Test (Test Uwagi i Spostrzegawczości TUS), Frontal Behavioral Inventory (FBI). Results. The review of the literature suggest cerebellar participation, especially the vermis and paravermial regions, in the detection, integration and filtration of emotional information and in regulation of autonomic emotional responses. In the described patients we observed: oversensitivity, irritability, impulsivity and self-neglect. -

Reading Braniacs

Reading Brainiacs Adeetee Bhide, University of Pittsburgh Unlike learning to speak, learning to read and write requires years of explicit instruction. However, once a person learns to read well, reading is effortless, and in fact, obligatory. Skilled adult readers cannot refrain from reading, even if reading is impairing their performance. To demonstrate this, take the very simple Stroop test 1 In the lists below, try to name the ink color of each word out loud (so, for the first list you would say "red, green, blue…”. List 1 List 2 Table Computer Green Purple Chair Sofa Red Red Book Plate Green Green Paper Mug Blue Purple Which list did you find easier? The first list was probably much easier than the second. That is because, even though the written words are completely irrelevant to the task, as skilled adult readers we cannot stop reading them. In the first list, the written words are simply random objects. However, in the second list, the written words are the incorrect colors, and they interfere with our production of the correct answer. How do we go from struggling to read, sounding out one letter at a time, to becoming such skilled readers that we cannot even prevent ourselves from reading? And how does the brain change during the process of becoming a skilled reader? This article examines the neural mechanisms that underlie our ability to read. The beginning largely focuses on English, because the majority of scientific research on reading has been done with English. Later, the article covers the neural mechanisms behind reading other languages, including the akshara languages. -

Nonverbal Processing in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

Nonverbal processing in frontotemporal lobar degeneration Dr Rohani Omar MA MRCP Submitted to University College London for the degree of MD(Res) 1 SIGNED DECLARATION I, Rohani Omar confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) refers to a group of diseases characterised by focal frontal and temporal lobe atrophy that collectively constitute a substantial source of clinical and social disability. Patients exhibit clinical syndromes that are dominated by a variety of nonverbal cognitive and behavioural features such as agnosias, altered emotional and social responses, impaired regulation of physiological drives, altered chemical sense, somatosensory and interoceptive processing. Brain mechanisms for processing nonverbal information are currently attracting much interest in the basic neurosciences and deficits of nonverbal processing are a major cause of clinical symptoms and disability in FTLD, yet these clinical deficits remain poorly understood and accurate diagnosis is often difficult to achieve. Moreover, the cognitive and neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural and nonverbal cognitive syndromes in FTLD remain largely undefined. The experiments described in this thesis aim to address the issues of improving our understanding of the social and behavioural symptoms in FTLD through the integration of detailed neuro-behavioural, neuropsychological and neuroanatomical analyses of a range of nonverbal functions (including emotions, sounds, odours and flavours) with high- resolution structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A prospective study of emotion recognition in various domains including music, faces and voices shows that music is especially vulnerable to the effects of damage in FTLD. -

Frontal Lobe Syndrome Treatment Pdf

Frontal lobe syndrome treatment pdf Continue Mesulam MM. Human frontal lobes: Overcoming the default mode through the coding of the continent. DT Stus and RT Knight. Principles of frontal lobe function. Oxford: 2002. 8-30. Bonelli RM, Cummings JL. Frontal subcortial circuit and behavior. Dialogues Wedge Neuroshi. 2007. 9(2):141-51. (Medline). Cruz-Oliver DM, Malmstrom TK, Allen CM, Tumosa N, Morley JE. University of St. Louis Veterans' Examination for Mental Status (SLUMS Exam) and Mini-Mental Status Examination as Predictors of Mortality and Institutionalization. J Natra is a health aging. 2012. 16(7):636-41. (Medline). Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvin I, Pillon B. FAB: Front battery scores at the bedside. Neurology. 2000 Dec 12. 55(11):1621-6. (Medline). Nasreddin S.S., Phillips N.A., Sdirian V et al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Short Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Apr 53 (4):695-9. (Medline). Copp B, Russer N, Tabeling S, Steurenburg Headquarters, De Haan B., KarnatHO, etc. Performance on the front battery scores are sensitive to frontal lobe damage in stroke patients. BMC Neurol. 2013 November 16. 1:179 p.m. (Medline). (Full text). Munoz DP, Everling S. Otadi: anti-sacdad task and voluntary eye control. Nat Rev Neuroshi. March 5, 2004. 5:218-28. (Medline). (Full text). Reitan RM. Trace ratio by doing a test for organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1955 October 19 (5):393-4. (Medline). Mall J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Mall FT, Bramati IE, Andreiuolo PA. Cerebral correlates with a change in the set: an MRI track study while doing a test. -

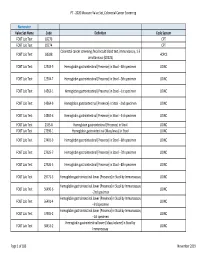

HMSA Payment Transformation 2020 Measure Value Set Breast Cancer

PT - 2020 Measure Value Set_Breast Cancer Screening Numerator Value Set Name Code Definition Code System Mammography 77055 CPT Mammography 77056 CPT Mammography 77057 CPT Mammography 77061 CPT Mammography 77062 CPT Mammography 77063 CPT Mammography 77065 CPT Mammography 77066 CPT Mammography 77067 CPT Screening mammography, bilateral (2-view study of each breast), including computer-aided Mammography G0202 HCPCS detection (cad) when performed (G0202) Diagnostic mammography, including computer-aided detection (cad) when performed; Mammography G0204 HCPCS bilateral (G0204) Diagnostic mammography, including computer-aided detection (cad) when performed; Mammography G0206 HCPCS unilateral (G0206) Mammography 87.36 Xerography of breast ICD9PCS Mammography 87.37 Other mammography ICD9PCS Mammography 24604-1 MG Breast Diagnostic Limited Views LOINC Mammography 24605-8 MG Breast Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 24606-6 MG Breast Screening LOINC Mammography 24610-8 MG Breast Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26175-0 MG Breast - bilateral Screening LOINC Mammography 26176-8 MG Breast - left Screening LOINC Mammography 26177-6 MG Breast - right Screening LOINC Mammography 26287-3 MG Breast - bilateral Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26289-9 MG Breast - left Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26291-5 MG Breast - right Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26346-7 MG Breast - bilateral Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 26347-5 MG Breast - left Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 26348-3 MG Breast - right Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 26349-1 MG Breast - bilateral Diagnostic -

2020 Measure Value Set Colorectal Cancer Screening

PT ‐ 2020 Measure Value Set_Colorectal Cancer Screening Numerator Value Set Name Code Definition Code System FOBT Lab Test 82270 CPT FOBT Lab Test 82274 CPT Colorectal cancer screening; fecal occult blood test, immunoassay, 1‐3 FOBT Lab Test G0328 HCPCS simultaneous (G0328) FOBT Lab Test 12503‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐4th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 12504‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐5th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14563‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐1st specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14564‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐2nd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14565‐6 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐3rd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 2335‐8 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27396‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Mass/mass] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27401‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐6th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27925‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐7th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27926‐5 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐8th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 29771‐3 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay LOINC Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56490‐6 LOINC ‐‐2nd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56491‐4 LOINC ‐‐3rd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 57905‐2 -

On Task: How Our Brain Gets Things Done

CONTENTS Acknowl edgments ix Chapter 1 What Lies in the Gap between Knowledge and Action? 1 Chapter 2 The Origins of Human Cognitive Control 32 Chapter 3 The Stability- Flexibility Dilemma 66 Chapter 4 Hierarchies in the Head 98 Chapter 5 The Tao of Multitasking 130 Chapter 6 Stopping 157 Chapter 7 The Costs and Benefits of Control 186 Chapter 8 The Information Retrieval Prob lem 221 Chapter 9 Cognitive Control over Lifespan 251 Chapter 10 Postscript: Getting Things oneD That Matter 293 Notes 301 Index 323 vii CHAPTER 1 What Lies in the Gap between Knowledge and Action? There is a lot of mystery in a cup of coffee— not just in the molecular structure of the drink or in the chemical interactions needed for that morning fix or even in the origin ofthose D- grade beans, though each of these surely contains mysteries in its own right. A cup of coffee is mysterious because scientists don’t really understand how it got ther e. Someone made the coffee, yes, but we stilldon ’t have a satisfying expla- nation of how that person’s brain successfully orchestrated the steps needed to make that coffee. When we set a goal, like making coffee, how does our brain plan and execute the par tic u lar actions we take to achieve it? In other words, how do we get things done? Questions like these fascinate me because they lie close to the heart of what it means to be hu man. Our species has a uniquely power ful capacity to think, plan, and act in productive, often inge- nious, ways. -

Effects of Aging on Functions of the Prefrontal Cortex

EFFECTS OF AGING ON FUNCTIONS OF THE PREFRONTAL CORTEX *A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by GEOFFREY ARTHUR FOX, Bachelor of Arts DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY 2004 Aging and Prefrontal Functions ii CERTIFICATION I, Geoffrey A. Fox, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Psychology, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Geoffrey A. Fox Date: Aging and Prefrontal Functions iii Table of Contents CERTIFICATION...............................................................................................................ii Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................iii CHAPTER ONE: GERIATRIC NEUROPSYCHOLOGY ...............................................1 1.1 The concept of aging. .............................................................................................1 1.2 Methodologies in research on age-related issues...................................................3 CHAPTER TWO - EVOLUTION, DEVELOPMENT, MATURATION AND INVOLUTION....................................................................................................................6 2.1 Evolution................................................................................................................6 -

The Criminal Brain: Frontal Lobe Dysfunction Evidence in Capital Proceedings, 16 Cap

Capital Defense Journal Volume 16 | Issue 2 Article 4 Spring 3-1-2004 The rC iminal Brain: Frontal Lobe Dysfunction Evidence in Capital Proceedings Jessie A. Seiden Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlucdj Part of the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Jessie A. Seiden, The Criminal Brain: Frontal Lobe Dysfunction Evidence in Capital Proceedings, 16 Cap. DEF J. 395 (2004). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlucdj/vol16/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capital Defense Journal by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Criminal Brain: Frontal Lobe Dysfunction Evidence in Capital Proceedings Jessie A. Seiden* L Inxaion Something was wrong with the 40-year-old schoolteacher from Virginia.' From all outward appearances he seemed to be living a completely normal life.2 What others did not know was that he had begun collecting child pornography, soliciting prostitutes, and making sexual advances toward his stepdaughter.3 Eventually his wife found out and he was ordered either to complete a Sexaholics Anonymous program or face jail time.4 Despite the threat of jailtime, he failed the program because he could not stop himself from asking the other members for sexual favors.' The night before he was scheduled for sentencing, the man went to a hospital and complained of severe headaches.' During his hospitalization the man continued acting out and even propositioned nurses.7 Doctors performed a neurologic exam and discovered a large brain tumor displacing his orbitofrontal lobe.8 After the tumor was removed, the deviant urges subsided and he was allowed to return home.' * J.D. -

The Brain-Disordered Defendant: Neuroscience and Legal Insanity in the Twenty-First Century

American University Law Review Volume 56 | Issue 1 Article 7 2006 The rB ain-Disordered Defendant: Neuroscience and Legal Insanity in the Twenty-First Century Richard E. Redding Chapman University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Redding, Richard E. “The rB ain-Disordered Defendant: Neuroscience and Legal Insanity in the Twenty-First Century.” American University Law Review 56, no. 1 (October 2006): 51-127. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The rB ain-Disordered Defendant: Neuroscience and Legal Insanity in the Twenty-First Century Abstract Brain-damaged defendants are seen everyday in American courtrooms, and in many cases, their criminal behavior appears to be the product of extremely poor judgment and self-control. Some have a disorder in the frontal lobes, the area of the brain responsible for judgment and impulse control. Yet because defendants suffering from frontal lobe dysfunction usually understand the difference between right and wrong, they are unable to avail themselves of the only insanity defense available in many states, a defense based on the narrow McNaghten test. "Irresistible impulse" (or "control") tests, on the other hand, provide an insanity defense to those who committed a crime due to their inability to exercise behavioral control. -

Cognitive Impairment and Conversion to Dementia in Parkinson's Disease

University of Otago Doctoral Thesis Cognitive Impairment and Conversion to Dementia in Parkinson's Disease: An Imaging Study of Amyloid PET and Diffusion MRI Supervisors: Dr. Tracy R. Melzer (Primary) Author: Dr. Daniel J. Myall Megan Rebecca Stark Prof. Tim J. Anderson Prof. John C. Dalrymple-Alford Dr. Steven H. Marsh A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago Department of Medicine June 2020 Abstract Cognitive Impairment and Conversion to Dementia in Parkinson's Disease: An Imaging Study of Amyloid PET and Diffusion MRI by Megan Rebecca Stark Objective To investigate the association between amyloid deposition or white matter degeneration with cognitive impairment and conversion to dementia in Parkinson's disease (PD). Background Cognitive decline and dementia are common in Parkinson's disease, however the patho- physiological basis of cognitive impairment in PD is unresolved. The time-course from diagnosis to development of dementia is highly variable, and imaging biomarkers are ur- gently needed to assist estimation of long-term cognitive outcomes, and enable targeted therapeutic interventions in early disease. Misfolded beta-amyloid protein aggregates, or amyloid plaques, are a significant pathology in Alzheimer's disease, and may play a part in future cognitive decline in PD. Measures of cerebral blood flow and white mat- ter micro- and macro-structural degeneration may correlate more directly with current cognitive impairment, and may interact with amyloid to affect cognitive decline in PD. This thesis comprehensively investigates these measures in PD and aims to differentiate pathology and age-related effects, using both cross-sectional and longitudinal (three-year) study designs. -

Intertemporal Decision Making After Brain Injury: Amount-Dependent Steeper Discounting After Frontal Cortex Damage

Polish Psychological Bulletin Original Papers 2017, vol. 48(4) 456–463 DOI - 10.1515/ppb-2017-0052 Wojciech Białaszek* Bartłomiej Swebodziński* Paweł Ostaszewski* Intertemporal Decision Making After Brain Injury: Amount-Dependent Steeper Discounting after Frontal Cortex Damage Abstract: Traumatic brain injuries to the frontal lobes are associated with many maladaptive forms of behavior. We investigated the association between brain damage and impulsivity, as measured by the rate of delay discounting (i.e., the extent to which future outcomes are devalued in time). The main aim of this study was to test the hypothesis of steeper discounting of different amounts in a group of patients with frontal lobe damage. We used a delay discounting task in the form of a structured interview. A total of 117 participants were divided into five groups: three neurological groups and two groups without brain damage. Our analyses showed that patients with focal damage to the frontal lobes demonstrated steeper delay discounting than other participants. Other clinical groups demonstrated similar discounting rates. The data pattern related to the magnitude effect on the group level suggested that the magnitude effect is absent in the group of patients with damage to the frontal lobes; however, results were less consistent on an individual level. Amount-dependent discounting was observed in only two groups, the healthy control group and the neurological group with other cortical areas damaged. Keywords: impulsivity, brain injury, delay discounting, frontal lobes, magnitude effect Introduction to influence present decisions. Specifically, it is a choice of the smaller sooner reward over the larger later one. One From the molar point of view, maladaptive decision of the proposed mechanisms of the impulsive behavior is making in the intertemporal choice-behavior involves not delay discounting, which is the process by which delayed taking into account future, delayed consequences, and can outcomes are devalued.