The Criminal Brain: Frontal Lobe Dysfunction Evidence in Capital Proceedings, 16 Cap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distance Learning Program Anatomy of the Human Brain/Sheep Brain Dissection

Distance Learning Program Anatomy of the Human Brain/Sheep Brain Dissection This guide is for middle and high school students participating in AIMS Anatomy of the Human Brain and Sheep Brain Dissections. Programs will be presented by an AIMS Anatomy Specialist. In this activity students will become more familiar with the anatomical structures of the human brain by observing, studying, and examining human specimens. The primary focus is on the anatomy, function, and pathology. Those students participating in Sheep Brain Dissections will have the opportunity to dissect and compare anatomical structures. At the end of this document, you will find anatomical diagrams, vocabulary review, and pre/post tests for your students. The following topics will be covered: 1. The neurons and supporting cells of the nervous system 2. Organization of the nervous system (the central and peripheral nervous systems) 4. Protective coverings of the brain 5. Brain Anatomy, including cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum and brain stem 6. Spinal Cord Anatomy 7. Cranial and spinal nerves Objectives: The student will be able to: 1. Define the selected terms associated with the human brain and spinal cord; 2. Identify the protective structures of the brain; 3. Identify the four lobes of the brain; 4. Explain the correlation between brain surface area, structure and brain function. 5. Discuss common neurological disorders and treatments. 6. Describe the effects of drug and alcohol on the brain. 7. Correctly label a diagram of the human brain National Science Education -

Emotional Disorders in Patients with Cerebellar Damage - Case Studies

Should be cited as: Psychiatr. Pol. 2014; 48(2): 289–297 PL ISSN 0033-2674 www.psychiatriapolska.pl Emotional disorders in patients with cerebellar damage - case studies Katarzyna Siuda 1, Adrian Andrzej Chrobak 1, Anna Starowicz-Filip2, Anna Tereszko1, Dominika Dudek 3 1Students’ Scientific Association of Adult Psychiatry, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Tutor: prof. dr hab. med. D. Dudek 2Medical Psychology Department, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Head: prof. dr hab. n. hum. J.K. Gierowski 3Department of Affective Disorders, Jagiellonian University Medical College Head: prof. dr hab. med. D. Dudek Summary Aim. Growing number of research shows the role of the cerebellum in the regulation of affect. Lesions of the cerebellum can lead to emotional disregulation, a significant part of the Cerebellar Cognitive Affective Syndrome. The aim of this article is to analyze the most recent studies concerning the cerebellar participation in emotional reactions and to present three cases: two female and one male who suffered from cerebellar damage and presented post-traumatic affective and personality change. Method. The patients’ neuropsychological examination was performed with Raven’s Progressive Matrices Test – standard version, Trial Making Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Auditory Verbal Learning Test by Łuria, Benton Visual Retention Test, Verbal Fluency Test, Stroop Interference Test, Attention and Perceptivity Test (Test Uwagi i Spostrzegawczości TUS), Frontal Behavioral Inventory (FBI). Results. The review of the literature suggest cerebellar participation, especially the vermis and paravermial regions, in the detection, integration and filtration of emotional information and in regulation of autonomic emotional responses. In the described patients we observed: oversensitivity, irritability, impulsivity and self-neglect. -

The Brain Is Contained Within the Cranium, and Constitutes the Upper, Greatly Expanded Part of the Central Nervous System

The brain is contained within the cranium, and constitutes the upper, greatly expanded part of the central nervous system. Henry Gray (1918) Looking through the gray outer layer of the cortex, you can see a mass of white matter. At the center is a cluster of large nuclei, including the basal ganglia, the hippocampi, the amygdalae, and two egg-shaped structures at the very center, barely visible in this figure, the thalami. The thalami rest on the lower brainstem (dark and light blue). You can also see the pituitary gland in front (beige), and the cerebellum at the rear of the brain (pink). In this chapter we will take these structures apart and re-build them from the bottom up. 09_P375070_Ch05.indd 126 1/29/2010 4:08:25 AM CHAPTER 5 The brain OUTLINE 1.0 Introduction 127 3.2 Output and input: the front-back division 143 1.1 The nervous system 128 3.3 The major lobes: visible and hidden 145 1.2 The geography of the brain 129 3.4 The massive interconnectivity of the cortex and thalamus 149 2.0 Growing a brain from the bottom up 133 3.5 The satellites of the subcortex 151 2.1 Evolution and personal history are expressed in the brain 133 4.0 Summary 153 2.2 Building a brain from bottom to top 134 5.0 Chapter review 153 3.0 From ‘ where ’ to ‘ what ’ : the functional 5.1 Study questions 153 roles of brain regions 136 5.2 Drawing exercises 153 3.1 The cerebral hemispheres: the left-right division 136 1.0 INTRODUCTION found. -

Reading Braniacs

Reading Brainiacs Adeetee Bhide, University of Pittsburgh Unlike learning to speak, learning to read and write requires years of explicit instruction. However, once a person learns to read well, reading is effortless, and in fact, obligatory. Skilled adult readers cannot refrain from reading, even if reading is impairing their performance. To demonstrate this, take the very simple Stroop test 1 In the lists below, try to name the ink color of each word out loud (so, for the first list you would say "red, green, blue…”. List 1 List 2 Table Computer Green Purple Chair Sofa Red Red Book Plate Green Green Paper Mug Blue Purple Which list did you find easier? The first list was probably much easier than the second. That is because, even though the written words are completely irrelevant to the task, as skilled adult readers we cannot stop reading them. In the first list, the written words are simply random objects. However, in the second list, the written words are the incorrect colors, and they interfere with our production of the correct answer. How do we go from struggling to read, sounding out one letter at a time, to becoming such skilled readers that we cannot even prevent ourselves from reading? And how does the brain change during the process of becoming a skilled reader? This article examines the neural mechanisms that underlie our ability to read. The beginning largely focuses on English, because the majority of scientific research on reading has been done with English. Later, the article covers the neural mechanisms behind reading other languages, including the akshara languages. -

Nonverbal Processing in Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration

Nonverbal processing in frontotemporal lobar degeneration Dr Rohani Omar MA MRCP Submitted to University College London for the degree of MD(Res) 1 SIGNED DECLARATION I, Rohani Omar confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) refers to a group of diseases characterised by focal frontal and temporal lobe atrophy that collectively constitute a substantial source of clinical and social disability. Patients exhibit clinical syndromes that are dominated by a variety of nonverbal cognitive and behavioural features such as agnosias, altered emotional and social responses, impaired regulation of physiological drives, altered chemical sense, somatosensory and interoceptive processing. Brain mechanisms for processing nonverbal information are currently attracting much interest in the basic neurosciences and deficits of nonverbal processing are a major cause of clinical symptoms and disability in FTLD, yet these clinical deficits remain poorly understood and accurate diagnosis is often difficult to achieve. Moreover, the cognitive and neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural and nonverbal cognitive syndromes in FTLD remain largely undefined. The experiments described in this thesis aim to address the issues of improving our understanding of the social and behavioural symptoms in FTLD through the integration of detailed neuro-behavioural, neuropsychological and neuroanatomical analyses of a range of nonverbal functions (including emotions, sounds, odours and flavours) with high- resolution structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A prospective study of emotion recognition in various domains including music, faces and voices shows that music is especially vulnerable to the effects of damage in FTLD. -

Frontal Lobe Syndrome Treatment Pdf

Frontal lobe syndrome treatment pdf Continue Mesulam MM. Human frontal lobes: Overcoming the default mode through the coding of the continent. DT Stus and RT Knight. Principles of frontal lobe function. Oxford: 2002. 8-30. Bonelli RM, Cummings JL. Frontal subcortial circuit and behavior. Dialogues Wedge Neuroshi. 2007. 9(2):141-51. (Medline). Cruz-Oliver DM, Malmstrom TK, Allen CM, Tumosa N, Morley JE. University of St. Louis Veterans' Examination for Mental Status (SLUMS Exam) and Mini-Mental Status Examination as Predictors of Mortality and Institutionalization. J Natra is a health aging. 2012. 16(7):636-41. (Medline). Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvin I, Pillon B. FAB: Front battery scores at the bedside. Neurology. 2000 Dec 12. 55(11):1621-6. (Medline). Nasreddin S.S., Phillips N.A., Sdirian V et al. Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Short Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Apr 53 (4):695-9. (Medline). Copp B, Russer N, Tabeling S, Steurenburg Headquarters, De Haan B., KarnatHO, etc. Performance on the front battery scores are sensitive to frontal lobe damage in stroke patients. BMC Neurol. 2013 November 16. 1:179 p.m. (Medline). (Full text). Munoz DP, Everling S. Otadi: anti-sacdad task and voluntary eye control. Nat Rev Neuroshi. March 5, 2004. 5:218-28. (Medline). (Full text). Reitan RM. Trace ratio by doing a test for organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1955 October 19 (5):393-4. (Medline). Mall J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Mall FT, Bramati IE, Andreiuolo PA. Cerebral correlates with a change in the set: an MRI track study while doing a test. -

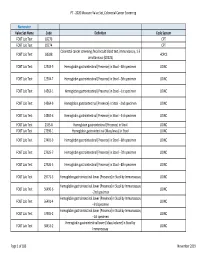

HMSA Payment Transformation 2020 Measure Value Set Breast Cancer

PT - 2020 Measure Value Set_Breast Cancer Screening Numerator Value Set Name Code Definition Code System Mammography 77055 CPT Mammography 77056 CPT Mammography 77057 CPT Mammography 77061 CPT Mammography 77062 CPT Mammography 77063 CPT Mammography 77065 CPT Mammography 77066 CPT Mammography 77067 CPT Screening mammography, bilateral (2-view study of each breast), including computer-aided Mammography G0202 HCPCS detection (cad) when performed (G0202) Diagnostic mammography, including computer-aided detection (cad) when performed; Mammography G0204 HCPCS bilateral (G0204) Diagnostic mammography, including computer-aided detection (cad) when performed; Mammography G0206 HCPCS unilateral (G0206) Mammography 87.36 Xerography of breast ICD9PCS Mammography 87.37 Other mammography ICD9PCS Mammography 24604-1 MG Breast Diagnostic Limited Views LOINC Mammography 24605-8 MG Breast Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 24606-6 MG Breast Screening LOINC Mammography 24610-8 MG Breast Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26175-0 MG Breast - bilateral Screening LOINC Mammography 26176-8 MG Breast - left Screening LOINC Mammography 26177-6 MG Breast - right Screening LOINC Mammography 26287-3 MG Breast - bilateral Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26289-9 MG Breast - left Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26291-5 MG Breast - right Limited Views LOINC Mammography 26346-7 MG Breast - bilateral Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 26347-5 MG Breast - left Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 26348-3 MG Breast - right Diagnostic LOINC Mammography 26349-1 MG Breast - bilateral Diagnostic -

Diverging Patterns of Atrophy and Hypometabolism in Syndromic

Simultaneous PET-MRI studies of the concordance of atrophy and hypometabolism in syndromic variants of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia: an extended case series *Kuven K Moodley1, *Daniela Perani2, Ludovico Minati1,3, Pasquale Anthony Della Rosa4, Frank Pennycook5, John C Dickson6, Anna Barnes6, Valeria Elisa Contarino7, Sofia Michopoulou7, Ludovico D’Incerti7, Catriona Good8, Federico Fallanca2, Emilia Giovanna Vanoli2, Peter J Ell6, and Dennis Chan1 *These authors equally contributed to the work 1Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Falmer, UK 2 Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Nuclear Medicine Unit San Raffaele Hospital, Division of Neuroscience IRCCS San Raffaele, Milano, Italy 3Scientific Department, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy 4Institute of Molecular Bio-imaging and Physiology, National Research Council, Milano, Italy 5Open University, Milton Keynes, UK 6Institute of Nuclear Medicine, University College London, London, UK 7Neuroradiology Department, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milano, Italy 8Hurstwood Park Neurosciences Centre, West Sussex, UK Corresponding Author: Dr Dennis Chan Herchel Smith Building for Brain and Mind Sciences Department of Clinical Neurosciences University of Cambridge Forvie Site, Robinson Way Cambridge CB2 0SZ Email: [email protected] Word count Abstract 278 Main Text 4969 Tables 1 Figures 6 Supplementary Figures 6 1 Abstract Aims. The primary objective was to determine the concordance of brain atrophy and hypometabolism in six syndromic variants of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontotemporal dementia spectrum (FTD). A second objective was to determine the effect of image analysis methods on identification of atrophy and hypometabolism by comparing the changes observed through qualitative rating with those detected by quantitative methods. -

2020 Measure Value Set Colorectal Cancer Screening

PT ‐ 2020 Measure Value Set_Colorectal Cancer Screening Numerator Value Set Name Code Definition Code System FOBT Lab Test 82270 CPT FOBT Lab Test 82274 CPT Colorectal cancer screening; fecal occult blood test, immunoassay, 1‐3 FOBT Lab Test G0328 HCPCS simultaneous (G0328) FOBT Lab Test 12503‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐4th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 12504‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐5th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14563‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐1st specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14564‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐2nd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 14565‐6 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐3rd specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 2335‐8 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27396‐1 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Mass/mass] in Stool LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27401‐9 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐6th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27925‐7 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐7th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 27926‐5 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal [Presence] in Stool ‐‐8th specimen LOINC FOBT Lab Test 29771‐3 Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay LOINC Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56490‐6 LOINC ‐‐2nd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 56491‐4 LOINC ‐‐3rd specimen Hemoglobin.gastrointestinal.lower [Presence] in Stool by Immunoassay FOBT Lab Test 57905‐2 -

Brown Medical School Biomed 370 the Brain and Human Behavior

Brown Medical School Biomed 370 The Brain and Human Behavior The Brain and Human Behavior Biomed 370 A first year, second semester course sponsored by the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior Course Directors: Robert Boland, M.D. 455-6417 (office), 455-6497 (fax) [email protected] Stephen Salloway, M.D., M.S. 455-6403 (office), 455-6405 (fax) [email protected] Web site available through WebCT Teaching Assistants: Nancy Brim ([email protected]) Marisa Kastoff ([email protected]) Stan Pelosi ([email protected]) Grace Farris ([email protected]) Table of Contents. Overall Course Objectives.....................................................................4 Section 1. Basic Principles. ...................................................................7 Chapter 1. Limbic System Anatomy........................................................8 Chapter 2. Frontal Lobe Function And Dysfunction..............................13 Chapter 3. Clinical Neurochemistry......................................................19 Chapter 4. The Neurobiology Of Memory............................................36 Chapter 5. The Control Of Feeding Behavior .......................................46 Chapter 6. Principles Of Pharmacology................................................51 Chapter 7. Principles Of Neuroimaging.................................................55 Chapter 8. The Mental Status Examination...........................................74 Section 2. The Clinical Disorders.......................................................89 -

SAY: Welcome to Module 1: Anatomy & Physiology of the Brain. This

12/19/2018 11:00 AM FOUNDATIONAL LEARNING SYSTEM 092892-181219 © Johnson & Johnson Servicesv Inc. 2018 All rights reserved. 1 SAY: Welcome to Module 1: Anatomy & Physiology of the Brain. This module will strengthen your understanding of basic neuroanatomy, neurovasculature, and functional roles of specific brain regions. 1 12/19/2018 11:00 AM Lesson 1: Introduction to the Brain The brain is a dense organ with various functional units. Understanding the anatomy of the brain can be aided by looking at it from different organizational layers. In this lesson, we’ll discuss the principle brain regions, layers of the brain, and lobes of the brain, as well as common terms used to orient neuroanatomical discussions. 2 SAY: The brain is a dense organ with various functional units. Understanding the anatomy of the brain can be aided by looking at it from different organizational layers. (Purves 2012/p717/para1) In this lesson, we’ll explore these organizational layers by discussing the principle brain regions, layers of the brain, and lobes of the brain. We’ll also discuss the terms used by scientists and healthcare providers to orient neuroanatomical discussions. 2 12/19/2018 11:00 AM Lesson 1: Learning Objectives • Define terms used to specify neuroanatomical locations • Recall the 4 principle regions of the brain • Identify the 3 layers of the brain and their relative location • Match each of the 4 lobes of the brain with their respective functions 3 SAY: Please take a moment to review the learning objectives for this lesson. 3 12/19/2018 11:00 AM Directional Terms Used in Anatomy 4 SAY: Specific directional terms are used when specifying the location of a structure or area of the brain. -

On Task: How Our Brain Gets Things Done

CONTENTS Acknowl edgments ix Chapter 1 What Lies in the Gap between Knowledge and Action? 1 Chapter 2 The Origins of Human Cognitive Control 32 Chapter 3 The Stability- Flexibility Dilemma 66 Chapter 4 Hierarchies in the Head 98 Chapter 5 The Tao of Multitasking 130 Chapter 6 Stopping 157 Chapter 7 The Costs and Benefits of Control 186 Chapter 8 The Information Retrieval Prob lem 221 Chapter 9 Cognitive Control over Lifespan 251 Chapter 10 Postscript: Getting Things oneD That Matter 293 Notes 301 Index 323 vii CHAPTER 1 What Lies in the Gap between Knowledge and Action? There is a lot of mystery in a cup of coffee— not just in the molecular structure of the drink or in the chemical interactions needed for that morning fix or even in the origin ofthose D- grade beans, though each of these surely contains mysteries in its own right. A cup of coffee is mysterious because scientists don’t really understand how it got ther e. Someone made the coffee, yes, but we stilldon ’t have a satisfying expla- nation of how that person’s brain successfully orchestrated the steps needed to make that coffee. When we set a goal, like making coffee, how does our brain plan and execute the par tic u lar actions we take to achieve it? In other words, how do we get things done? Questions like these fascinate me because they lie close to the heart of what it means to be hu man. Our species has a uniquely power ful capacity to think, plan, and act in productive, often inge- nious, ways.