Fear and Consolation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Peter Canisius

Monthly Bulletin Mass Schedule for June 2018 The June 2018 DATE DAY MASS LOCATION TIME CHOIR Jun 2, 9, 30 Sat All Saturday Masses St. Theresia 3:30 PM Eucharistic Sounds Jun 16, 23 Sat All Saturday Masses St. Theresia 3:30 PM Elfacs Choir t. Peter Canisius Jun 3 Sun Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and St. Theresia 3:00 PM Voices of Praise Blood of Christ (Corpus Christi) International Catholic Parish Jun 10 Sun 10th Sunday in Ordinary Time St. Theresia 3:00 PM The Choir Immortal S Jun 17 Sun 11th Sunday in Ordinary Time St. Theresia 3:00 PM Elfacs Choir Jun 24 Sun Solemnity of the Birth of John the St. Theresia 3:00 PM The Choir Immortal Baptist (12th Sunday in Ordinary Participation in Politics Time) Beloved Sisters and Brothers, Jun 4, 11 Sun All Sunday Masses Canisius 6:00 PM Elfacs Choir Jun 18 Sun 10th Sunday in Ordinary Time Canisius 6:00 PM Praise God Choir On the 30th May 2018 the Commission for the Laity of the Indonesian Bishops’ Conference Feasts, Solemnities & Memorials GEREJA SANTA THERESIA issued a moral appeal in view of the upcoming Jun 1 - St. Justin, martyr Jl. Gereja Theresia No.2 local elections. It says among others: “Politics is Jun 2 - St. Marcellinus and Peter, martyrs Jakarta 10350 basically good as a means to actualize the Tel: 391 7806 nd Jun 3 - St. Charles Lwanga and Companions, martyrs 2 Collection Fax: 3989 9623 common good. Politics itself contains noble Jun 8 - The Most Sacred Heart of Jesus values such as service, dedication, sacrifice, Jun 11 - St. -

St. Peter Canisius Catholic.Net

St. Peter Canisius Catholic.net Son of Jacob Canisius, a wealthy burgomeister, and Ægidia van Houweningen, who died shortly after Peter’s birth. Educated in Cologne, Germany, studying art, civil law and theology. He was an excellent student, and received a master’s degree by age 19; his closest friends at university were monks and clerics. Joined in the Jesuits on 8 May 1543 after attending a retreat conducted by Blessed Peter Faber. Taught at the University of Cologne, and helped found the first Jesuit house in the city. Ordained in 1546. Theologian of Cardinal Otto Truchsess von Waldburg, Bishop of Augsburg in 1547. He travelled and worked with Saint Ignatius of Loyola who was his spiritual director in Rome, Italy. Taught rhetoric in Messina, Sicily in 1548, preaching in Italian and Latin. Doctor of theology in 1549. Began teaching theology and preaching at Ingolstadt, Germany in 1549. Rector of the university in 1550. Began teaching theology, preaching in the Cathedral of Saint Stephen in Vienna, Austria in 1552; the royal court confessor, he continued to worked in hospitals and prisons, and during Lent in 1553 he travelled to preach in abandoned parishes in Lower Austria. During Mass one day he received a vision of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and ever after offered his work to the Sacred Heart. He led the Counter-Reformation in Germany, Austria, Bohemia, and Switzerland, and his work led to the return of Catholicism to Germany. His catechism went through 200 editions during his life, and was translated into 12 languages; in some places catechisms were referred to as Canisi. -

Peter Canisius and the Protestants a Model of Ecumenical Dialogue?

journal of jesuit studies 1 (2014) 373-399 brill.com/jjs Peter Canisius and the Protestants A Model of Ecumenical Dialogue? Hilmar M. Pabel Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada [email protected] Abstract Some modern interpreters have incorrectly suggested that Peter Canisius was an ecumenist before his time. Their insistence on his extraordinary kindness towards Protestants does not stand the test of the scrutiny of the relevant sources. An analysis of Canisius’s advice on how Jesuits should deal with “heretics” in Germany, of his catechisms, and of his polemical works reveals a typical Catholic controversialist of the Reformation era. Canisius was disposed to display hostility, more than good will, to Protestants. Keywords Peter Canisius – Protestants – Reformation – apologetics Introduction: The Celebration of a Saint Peter Canisius’s path to canonization was a long one. He died in 1597. The for- mal ecclesiastical process to declare him a saint began in 1625, but his beatifica- tion, solemnly pronounced by Pope Pius IX, had to wait until 1864.1 In Militantis ecclesiae (1897), Pope Leo XIII marked the 300th anniversary of Canisius’s death by hailing him as “the second apostle of Germany.” St. Boniface, the eighth- century Anglo-Saxon missionary, was the first. Pius XI not only canonized Canisius in 1925; he also declared him a doctor of the universal church.2 This 1 Forian Rieß, Der selige Petrus Canisius aus der Gesellschaft Jesu (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1865), 552, 554. 2 Otto Braunsberger, “Sanctus Petrus Canisius Doctor Ecclesiae,” Gregorianum 6 (1925): 338. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2014 | doi 10.1163/22141332-00103002Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 04:37:36AM via free access <UN> 374 Pabel was a rare distinction, as Yves de la Brière reported two weeks later in the Jesuit journal Études. -

St. Irenaeus Parish, Park Forest, Illinois December 16, 2018 Third Sunday of Advent Advent/Christmas 2018

St. Irenaeus Parish, Park Forest, Illinois December 16, 2018 Third Sunday of Advent Advent/Christmas 2018 First Sunday of Advent Sunday, December 2 5:00 P.M. 8:30 A.M. 10:30 A.M. Saturday December 8 Immaculate Conception 8:00 A.M. Second Sunday of Advent Sunday, December 9 5:00 P.M. 8:30 A.M. 10:30 A.M. Adoration after the 10:30 A.M. mass ending with Benediction at 5:00 P.M. Third Sunday of Advent Sunday, December 16 5:00 P.M. 8:30 A.M. 10:30 A.M. Join in the Decorating Church for Christmas after 10:30 Mass Parish Reconciliation Service 4:00 P.M. Fourth Sunday of Advent Sunday, December 23 5:00 P.M. 8:30 A.M. 10:30 A.M. Monday December 24 Christmas Eve Family Mass w/Pageant 5:00 P.M. Choir Christmas Carols 7:30 P.M. Christmas Eve Liturgy 8:00 P.M. Tuesday December 25 Christmas Day Liturgy 9:30A.M. Monday December 31 New Years Eve 5:00 P.M. Tuesday January 1 New Years Day 9:00 A.M. Saturday January 5 Vigil for Epiphany 5:00 P.M. Sunday January 6 Epiphany of the Lord 8:30 A.M. 10:30 A.M. All above events will be held in church As we journey this Advent/Christmas season into the fullness of the Incarnation of God among us, may we come to know deep within, the light that shines in each of us! A light that pierces the darkness and shines into the world! Our light transforms the world, transforms the place where we are each and every day! May the light of the Advent season, symbolized in the flames of the Advent wreath, give us courage and perseverance that leads to compassion and joy this Christmas Day! Happy Advent! St. -

St Francis of Assisi Church & St Philip Benizi Mission

St Francis of Assisi Church & St Philip Benizi Mission Dec 13, 2020 MASS TIMESR Saturday: 4pm Reconciliation 5:30pm Mass at St. Francis Sunday: 7:30am & 9am Mass at St. Francis Sunday: 11am Mass at St. Philip of Benizi Mission in Darby Tuesday: 12:10pm at St. Francis Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday : 9am Mass at St. Francis Christmas Cards to the Homebound Members of St. Francis will be mailing Saturday, December 12 Christmas Cards to the homebound. 4pm Reconciliation 5:30 pm Mass at St. Francis If you, or someone you know is ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ homebound and would like to receive Sunday, December 13 a Christmas Card, please call Third Sunday of Advent 7:30am & 9am Mass at St. Francis Cathy at 961-5413. 11am Mass at St. Philip of Benizi (Darby) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Monday, December 14 NO Mass ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Tuesday, December 15 NO Mass Fridays following the 9am Mass at St. Francis ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Wednesday, December 16 8:30 Rosary in Chapel 9am Mass 9:30 Women of Faith 5:30pm Accountability Group 6pm JH/HS Religious Ed class ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Thursday, December 17 8:30 Rosary in Chapel 9am Mass ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Friday, December 18 8:30 Rosary in Chapel WEEKLY MASS INTENTIONS 9am Mass 9:30am Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament Sat Dec 12 5:30pm Mass: For Dr. Armon Meis by Philip, 5pm Community Meals (drive thru) Gailleigh & Timothy Meis ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Sun Dec 13 7:30am Mass: For Community of the Parish Saturday, December 19 4pm Confession 9am Mass: For Tom Ford by Jeannie Horner 4pm Rosary Makers 11am Mass: For Jude Todd by Terri 5:30pm Mass at St. -

I Worry Until Midnight and from Then on I Let God Worry

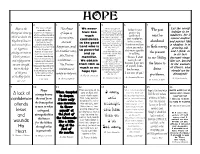

HOPE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The virtue of hope Hope is the The object We never The virtue of Let the world responds to the hope is so pleasing Today in your The past aspiration to happiness have too indulge in its theological virtue by of hope is, to God that He prayer you which God has placed in much has declared that confirmed must be madness, for it which we desire the the heart of every man; He feels delight in cannot endure it takes up the hopes in one way, confidence those who trust your resolution kingdom of heaven that inspire men's in Him: “The Lord to be a saint. abandoned and passes like eternal in the good taketh pleasure in activities and purifies I understand you a shadow. It is and eternal life as Lord who is them that hope them so as to order them happiness, and, in His Mercy” when you make to God's mercy, growing old, our happiness, to the Kingdom of so powerful (Ps. 46:11). this more specific heaven; it keeps man in another way, And He promises and I think, is placing our trust in from discouragement; and so victory over his by adding, the present in its last Christ's promises it sustains him during the Divine merciful. enemies, “I know I shall times of abandonment; perseverance in to our fidelity, decrepit stage. grace, and succeed, not and relying not on it opens up his heart in assistance . We obtain eternal glory to But we, buried expectation of eternal from Him as the man who because I am sure the future to in the wounds our own strength, beatitude. -

Third Sunday of Advent

December 15, 2013 THIRD SUNDAY OF ADVENT Pastor’s Notes: Sacrament of Reconciliation: Saturday, December 21 from 6 to 7 pm. Sunday, December 22 from 3 to 5 pm. Monday, December 23 from 6 to 7 pm. Christmas Mass Schedule: Christmas Eve at 4 pm. Christmas Day at 9 am. New Year’s Mass Schedule: New Year’s Eve at 5 pm. New Year’s Day at 9 am. Welcome Fr. Polycarp SSebowa! We are happy to have a visiting Priest to help celebrate the festivities of the Christmas Season with us. Fr. Polycarp comes from Uganda. He is currently on sabbatical and studying for a Masters Degree in Theology at Sacred Heart School of Theology, Hales Corners, Wisconsin, where incidentally Jeff Asmussen is in his first year of studies for the Priesthood. Father Polycarp will no doubt be joining Fr. Frank or myself at various Liturgies during the Christmas season. Please join me in extending a very warm welcome to him. With every blessing! Fr. Michael Stocking Stuffer Idea for your husband, your son, your father, your brother or your friend. Register him for the 2014 Catholic Men's Conference Men of Faith -Brothers in Christ. The conference is March 8, 2014 at the College of St. Scholastica. Registration available -on line at www.duluthcatholicmen.org. Only $25. Help Pope Francis and the upcoming Synod of Bishops to effectively respond to the pastoral needs of married couples and families! Note that you do not need to answer every question. The survey is due by December 18. The direct link to the survey is: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/Y8X9BTC. -

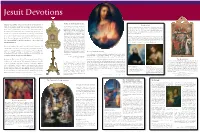

Jesuit Devotions

Jesuit Devotions Relics of Christ and the Saints Defining characteristics of that part of Catholic devotion known as Jesuit Saints Jesuit devotion derive from Jesuit spirituality, understood as those The Jesuits were active agents in promoting the cult of relics in their missions Jesuit iconography changed dramatically after 1622, with the canonization means used to draw a person closer to God that are particular to throughout the world. On the Feast of of the first Jesuit saints, Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier. From All Saints in 1578, the Jesuits organized a that point on, those and later Jesuit saints, (including Francis Borja, the insights of St. Ignatius Loyola and amplified by later Jesuits. Any festive reception of 214 relics of European Aloysius Gonzaga, and Stanislaus Kostka), occupied a dominant place in consideration of Jesuit devotion must be rooted in Ignatius’s Spiritual saints that Pope Gregory XIII (reigned 1572- Jesuit imagery and devotion. 1585) had sent them to be distributed in the Exercises, the foundational spiritual document of the Society of Jesus. churches of Mexico City. In order to guard While the iconography of the Society is varied, more and more of it came In the Exercises, Ignatius employed what has been described as a them, eighteen sumptuous reliquaries to be dominated by images of the saints, the blessed, and the martyrs of the of gold, silver and precious stones were order. This phenomenon marked the Jesuit enterprise throughout the world. “theology of visibility” to guide the exercitant to a knowledge of self crafted, which were taken in procession Whenever Jesuit saints were depicted together, Ignatius invariably stood at from the cathedral to the College of the their head, with Francis Xavier almost as invariably at his side. -

The Holy See

The Holy See BENEDICT XVI GENERAL AUDIENCE Paul VI Audience Hall Wednesday, 9 February 2011 [Video] Saint Peter Canisius Dear Brothers and Sisters, Today I want to talk to you about St Peter Kanis, Canisius in the Latin form of his surname, a very important figure of the Catholic 16th century. He was born on 8 May 1521 in Wijmegen, Holland. His father was Burgomaster of the town. While he was a student at the University of Cologne he regularly visited the Carthusian monks of St Barbara, a driving force of Catholic life, and other devout men who cultivated the spirituality of the so-called devotio moderna [modern devotion]. He entered the Society of Jesus on 8 May 1543 in Mainz (Rhineland — Palatinate), after taking a course of spiritual exercises under the guidance of Bl. Pierre Favre, Petrus [Peter] Faber, one of St Ignatius of Loyola’s first companions. He was ordained a priest in Cologne. Already the following year, in June 1546, he attended the Council of Trent, as the theologian of Cardinal Otto Truchsess von Waldburg, Bishop of Augsberg, where he worked with two confreres, Diego Laínez and Alfonso Salmerón. In 1548, St Ignatius had him complete his spiritual formation in Rome and then sent him to the College of Messina to carry out humble domestic duties. 2 He earned a doctorate in theology at Bologna on 4 October 1549 and St Ignatius assigned him to carry out the apostolate in Germany. On 2 September of that same year he visited Pope Paul III at Castel Gandolfo and then went to St Peter’s Basilica to pray. -

Peter Canisius John Donnelly Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 1-1-1981 Peter Canisius John Donnelly Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Peter Canisius," in Shapers of Religious Traditions in Germany, Switzerland, and Poland, 1560-1600. Eds. Jill Raitt. eN w Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981: 141-156. DOI. © 2008 Yale University Press. Used with permission. 9 l?eJreJR- ~RN151U5 1521-1597 JOHN PATRICK DONNELLY LIFE Peter Kanijs, or Canisius, was born at Nijmegen in 152 L Jakob Kanijs, Peter's father, was a man of culture who had attended the Universities of Paris and Orleans and had served as tutor to the sons of Duke Rene II of Lorraine. Later he proved an astute businessman and politician, serving nine terms as mayor ofNijmegen. As his eldest son, Peter received the best education available, first at the local Latin school, then at a nearby boarding establishment, and finally at the University of Cologne. Cologne was a natural choice, even though the university had fallen on evil days, for the Rhine !jnked it to Nijmegen, and Jakob Kanijs had business connections there. Among staunch Catholics such as the Kani;s family, C0- logne was renowned, as the German Rome, filled with old churches and relics of.the saints. Jakob entrusted his son to two outstanding priests, Andrew Herll and Nicholas van Esche, who introduced their fifteen-year-old charge to the Dutch and Rhenish spirituality of the late Middle Ages. Through van Esche, Canisiusbecame friendly with Gerard Kalckbrenner and Johannes Lanspergiy.s, the prior and subprior at the Charterhouse of St. -

Choosing a Name the Saints, Our Teachers Why a Saint for Confirmation? Saints Who I'm Pretty Sure Were Actually Superheroes

Choosing a Name The saints, our teachers Saints who I’m pretty sure were actually superheroes What an incredible gift we have in the communion of saints. The saints are No, their “superpowers” weren’t designed like us! They are our ancestors, our by fancy machinery or alien power. They teachers, our friends, our siblings. They were simply receptive to the mighty are real, truly human. They are sinners, power of God. These saints stories are they are repentant children of God. incredibly heroic. The saints lived on this earth and St. Mary, the Mother of God experienced suffering, joy, pain, broken promises, peace, frustration, war, injury, St. Peter heart-break… they know our hearts. But Bl. Miguel Pro mostly, they know what it takes to be united with God here on this messy St. Maximilian Kolbe earth. They know what it takes to live St. Joseph Cupertino well for Him. St. George Martyr Why a saint for St. Joan of Arc Confirmation? St. Padre Pio We choose a Confirmation saint (like we St. Louis IX choose a Confirmation sponsor) not out of due diligence to the “rule,” but rather St. George because we realize how unfortunate it St. Simeon Stylites would be to travel alone. We recognize how important it is to know your St. Quiteria Confirmation saint not only by name, but St. Denis also by story. The saints have so much to teach us about this journey. St. Margaret of Antioch The following list is for you to use as a St. Patrick starting point in your journey to decide whom your “Confirmation saint-buddy” will be. -

MS 113 Stanley: Misc

Corpus Christi College Cambridge / PARKER-ON-THE-WEB M.R. James, Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge 1912 MS 113 Stanley: Misc. A TJames: vac. Letters of Martin Bucer, Philipp Melanchthon etc. Letters of Bucer, Melanchthon etc. Codicology: Paper, mm 315 x 220 (12.33 x 8.5 in.), pp. 446 numbered. Additions: A fragment of the xvth cent. service-book, pasted over, serves as flyleaf. (ff. iiir-iiiv) Foliation: ff. i-iii + pp. 1-4 + 4a-5a + 5-14 (15-18 missing) + 19-72 + 72a-73a + 73-166 + 166a-167a + 167-206 + ff. 207a-h + 207j-k + pp. 209-228 + ff. 229-230 + pp. 231-328 + 328a-l + 329-446 + ff. iv-v. Language: Latin, English and Greek. Contents: 1. 1-4 Letter of Martin Bucer[] to Princess Elizabeth[] sister of Edward VI[] dated September 1549 Epistola [Buceri[]] ad dominam Elizabetham regis sororem[], data Lambethae[] 6 kal. Sept. 1549: in qua commendat ei peregrinum quendam qui religionis ergo in Angliam[] venerat 2. 4a-5a Letter of Roger Ascham[] to Princess Elizabeth[] dated November 1550 Epistola [ut videtur Aschami[]] data 13 kal. Nov. 1550, mittit dominae Elizabethae[] duo exemplaria libelli a Sturmio[] editi nomine autoris 3. 5-12 Letter of Martin Bucer[] to the Marquis of Dorchester[] dated 26 December 1550 Epistola [Buceri[]] ad Marchionem Dorcestrensem[] data 26 Dec. 1550, gratulatur ei quod in concilium supremum cooptatus esset, et multis argumentis suadet, ne bona ecclesiae olim dicata in alios usus alienentur, sed ad ministros Dei sustentandos et alios pios usus omnino applicentur See Gasquet and Bishop, Edward VI and the Book of Common Prayer, p.