Background of Busia County Matayos Is One of the Seven Sub-Counties in Busia County Lying Between Latitude 0 O N and 0010’ N Longitude 34 O E and 34 6’0 E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing a Mobile Diagnostic Unit to Increase Access to Imaging and Laboratory Services in Western Kenya

Practice Implementing a mobile diagnostic unit to increase access to imaging and laboratory services in western Kenya Roshni Dhoot,1 John M Humphrey,2,3 Patrick O'Meara,3,4 Adrian Gardner,2,3 Clement J McDonald,5 Kelvin Ogot,6 Sameer Antani,5 Joseph Abuya,7 Marc Kohli8 To cite: Dhoot R, Humphrey JM, O'Meara P, et al. Implementing ABSTRACT Summary box a mobile diagnostic unit to Access to basic imaging and laboratory services remains a increase access to imaging major challenge in rural, resource-limited settings in sub- and laboratory services in ► Access to basic imaging and laboratory services Saharan Africa. In 2016, the Academic Model Providing western Kenya. BMJ Glob Health in rural, resource-limited settings in sub-Saharan 2018;3:e000947. doi:10.1136/ Access to Healthcare programme in western Kenya Africa is limited, particularly in areas facing a high bmjgh-2018-000947 implemented a mobile diagnostic unit (MDU) outfitted with burden of tuberculosis. a generator-powered X-ray machine and basic laboratory ► In 2016, the Academic Model Providing Access to Handling editor Seye Abimbola tests to address the lack of these services at rural, low- Healthcare programme implemented a mobile diag- resource, public health facilities. The objective of this paper nostic unit (MDU) with a generator and wireless digi- Received 11 May 2018 is to describe the design, implementation, preliminary tal radiography which has taken over 4500 X-rays to Revised 8 August 2018 impact and operational challenges of the MDU in western date, detecting abnormalities in approximately 30% Accepted 9 August 2018 Kenya. -

Social Support for Orphaned Children in Busia Township: Challenges and Prospects

SOCIAL SUPPORT FOR ORPHANED CHILDREN IN BUSIA TOWNSHIP: CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS BY NETONDO WEPO MISIKO A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY MASENO UNIVERSITY ©2017 DECLARATION I declare that this work has not been previously submitted for a degree at Maseno or any other University. The work reported herein was carried out by me and all sources of information have been acknowledged. Netondo Wepo Misiko Reg. No. EL/ARM/00265/2012 Signature…………………………… Date……………………… This Project Report has been submitted for examination with my approval as University Supervisor Dr. Omondi Ahawo. Department of Sociology and Anthropology Maseno University Signature…………………………… Date……………………… ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my appreciation first and foremost to Mr and Mrs Gunner Ischir (Sigrid Zumbach and Gunner Ischir) of Baden Young Men Christian Association (YMCA), Germany, for the financial support and encouragement. Dr. Omondi Ahawo of the School of Arts and Social Sciences, Department of Sociology, Maseno University who was the course coordinator and my supervisor, for the encouragement and friendly engagement to ensure that I complete this undertaking. Dr. F. Ikanda, the Chair of the Department, for his invaluable guidance, my colleagues, Diida and Sylvia and the faculty in general, thank you all. This work is a reflection on how I would have loved to be supported as an orphan at the age of 8 months and tries to capture realities lived by Orphaned and Vulnerable Children in our communities. Lastly, Iwish to express sincere gratitude to my respondents who provided information for the study, specifically Matayos Sub-County children‟s officer who availed the sampling frame and guided me to locate the beneficiaries. -

The Long-Term Impacts of Youth Investments in Kenya on Economic Preferences Pre-Analysis Plan

The Long-Term Impacts of Youth Investments in Kenya on Economic Preferences Pre-Analysis Plan AEA RCT Title: Experimental Evidence on Child Health and Long-run Outcomes in Kenya RCT ID: AEARCTR-0001191 Principal Investigators: Livia Alfonsi (University of California, Berkeley), Michal Bauer (CERGE-EI and Charles University), Julie Chytilová (Charles University and CERGE-EI), Edward Miguel (University of California, Berkeley), and Michael Walker (University of California, Berkeley) Date: July 11, 2019 Appendix: KLPS-4 I Module Survey Instrument 1 Summary: This document outlines the plan for analyzing the long-term impacts of a series of child and adolescent health, skills and financial investments on a set of fundamental economic preferences. Our primary analysis will study the 20-year impacts of a randomized school deworming program in western Kenya using data from the fourth round of the Kenya Life Panel Survey (KLPS-4). The deworming analysis builds on that of Baird et al. (2016), using different outcome variables. The fourth round of KLPS was launched in 2018 and is currently ongoing. KLPS-4 also serves as the 10-year follow-up of a vocational training voucher program, and the 5-year follow-up of a cash grant program, and we analyze the impacts of these programs as a secondary analysis. The analysis outlined here will be split into five groups of outcomes: (1) time preference, (2) decision- making under uncertainty, (3) pro-social behavior, (4) anti-social behavior, and (5) preference for truth- telling. To measure preferences, we use experimentally validated survey measures or incentivized tasks. This document lays out the main regression specifications and outcome variable definitions that are intended for use for the long-term impacts analysis of these five groups of outcomes. -

Vocational Education Voucher Delivery and Labor Market Returns: a Randomized Evaluation Among Kenyan Youth

Vocational Education Voucher Delivery and Labor Market Returns: A Randomized Evaluation Among Kenyan Youth Report for Spanish Impact Evaluation Fund (SIEF) Phase II Joan Hamory Hicks, Michael Kremer, Isaac Mbiti, and Edward Miguel April 2011 Abstract This report describes the ongoing Technical and Vocational Vouchers Program (TVVP) in Kenya and provides early results from the intervention. Implementation began in 2008 with the recruitment of approximately 2,160 out-of-school youths (ranging in age from roughly 18 to 30). Study participants were drawn from the Kenya Life Panel Survey, an unusual on-going panel dataset of detailed educational, health, and cognitive information for over 7,000 adolescents in western Kenya. Of the 2,160 youths that applied to the TVVP, a random half were awarded a voucher for vocational training, while the other half served as the control group. Of the voucher winners, a random half were awarded a voucher that could only be used in public (government) institutions, while the other half received a voucher that could be used in either private or public institutions. The project also included a cross-cutting information intervention, which exposed a randomly selected half of all treatment and control individuals to information about the actual returns to vocational education. This report focuses on program take-up, the demand for vocational training and the impacts of the information intervention on institution and course selection, participant attendance, the short-term impacts of training on labor market expectations and outcomes for a representative subset of program participants, and training center characteristics. The report also provides some suggestive evidence on the supply-side impacts of the program. -

The Inside by Linked to Politicians – Including a Way Through Murder, Drug and Hu- in Government Institutions

SPECIAL REPORT The NEW LAW SEALS LOOPHOLES IN ELECTORAL PROCESS — Pages 14 & 19 SUPPLEMENT LEnhancingink governance for all THE PARTNERSHIP FOR PEACE PROJECT FUNDED BY THE EU NOVEMBER 2011 Issue No. 085 Kshs 40/= — Pages 15 - 18 Kenya risks being InsIde Is Bungoma ready for self a captured state government? By THE LINK WRITER —Pg. 4 ENYANS are seen to have a “business-as-usual” approach President Kibaki Kto corruption, but a new re- orders ministers port published by the International Peace Institute shows that our ex- to revive KPCU treme tolerance to impunity is having —Pg. 9 devastating consequences and is, in fact, undermining the State’s legiti- macy. Kibunjia assures Endemic corruption and powerful transna- Kenyans election tional criminal networks have entrenched state violence institutions and eroded public confidence in them, says the report by International Peace —Pg. 13 Institute. Peter Gastrow, the author of the report titled “Termites at Work: Transnational Or- State changes ganised Crime and State Erosion in Kenya” says that rampant corruption within the Police tact in race Force, the Judiciary and other State institu- against Aids tions has allowed criminals to penetrate politi- cal institutions. —Pg. 23 Powerful criminal networks with links to Parliament currently pose a big threat to the creation of laws, policies and regulations Bee keeping in that could help curb money laundering and Mwingi faces drug trafficking. Governments that lack the capacity or the political will to counter such imminent collapse penetration, he says, run the risk of becoming “captured states” – that is, states whose gov- —Pg. 27 ernment structures have become captives of Prof. -

County Integrated Development Plan 2018-2022 Departmental Visions and Missions Were Inspired by These Aspirations

BUSIA COUNTY COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018 - 2022 BUSIA COUNTY VISION: A transformative and progressive County for sustainable and equitable development MISSION: To provide high quality service to Busia residents through well governed institutions and equitable resource distribution CORE VALUES: Transparency: We encourage openness in sharing information between the County Government and the public Accountability: We hold ourselves answerable to the highest ideals of professionalism, ethics and competency Integrity: We believe that acting honorably is the foundation of everything we do and the basis of public trust Teamwork: We understand the strength of cooperation and collaboration and that our success depends on our ability to work together as one cohesive team Fairness: We have an open culture and are committed to providing equal opportunities for everyone Honesty: We insist on truthfulness with each other; with the citizens, we expect and value openness Equity: We believe in fairness for every resident in distribution of resources and opportunities ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................... x LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................. xii FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................... -

ANPPCAN Annual Report 2019

The African Network for the Prevention and Protection against Child Abuse and Neglect (ANPPCAN) ANNUAL REPORT The African Network for the Prevention and Protection against Child Abuse and Neglect Table of Contents 2019: THE YEAR IN BRIEF ..................................................................................................................... 1 ANPPCAN ACTIVITIES IN THE YEAR .............................................................................................. 2 THE PROGRAMMES .......................................................................................................................... 4 EMPOWERING CHILDREN AS ADVOCATES OF THEIR RIGHTS ................................................. 4 ACTIVITIES UNDERTAKEN ............................................................................................................... 5 Developing and implementing an exit strategy for 15 schools ............................................................ 5 What emerged: ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Strengthening the capacity of the child protection structures to provide quality services to children .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 THE PARENTS ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT PROGRAMME (PEEP) ................................... 11 CHILD HEADED HOUSEHOLDS (CHHS) .................................................................................... -

In Busia County, Kenya

Rehabilitation of Busia (Jn B1) A lupe (Jnc C43) By pass (5.0 km) in Busia County, Kenya ESIA Project Report (Final Copy) 23 September 2019 Project No.: 0410731 The business of sustainability Document title Rehabilitation of Busia (Jn B1) A lupe (Jnc C43) By pass (5.0 km) in Busia County, Kenya Document subtitle ESIA Project Report (Final Copy) Project No. 0410731 Date 23 September 2019 Version 2.0 Author As per document history below Client Name Mota – Engil Africa Document history ERM approval to issue Version Revision Author Reviewed by Name Date Comments 1.0: Draft 1 00 Barnabas Mike Everett Mike 23.09.2019 Draft 1 issued to Busheshe, Everett client for review Mercy Kuria, Gideon Owaga and Faith Angasa 2.0: Final 01 Barnabas Mike Everett Mike 23.09.2019 Final Copy of the Copy Busheshe, Everett ESIA Project Mercy Kuria, Report for Gideon Owaga Submission to and Faith NEMA Angasa www.erm.com Version: 2.0 Project No.: 0410731 Client: Mota – Engil Africa 23 September 2019 Signature Page 23 September 2019 Rehabilitation of Busia (Jn B1) A lupe (Jnc C43) By pass (5.0 km) in Busia County, Kenya ESIA Project Report (Final Copy) Mike Everett Partner ERM East Africa (Pty) Ltd Senteu Plaza, 1st Floor Cnr of Galana and Lenana Roads Kilimani P.O Box 29170-00100 Nairobi, Kenya T: +254 740 861 650/1 © Copyright 2019 by ERM Worldwide Group Ltd and / or its affiliates (“ERM”). All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of ERM. -

Inside Front Cover Spread

FRONT COVER ǘ1ǚ INSIDE FRONT COVER SPREAD ǘ2ǚ ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014 INSIDE FRONT COVER SPREAD ǘ3ǚ VISION Our vision is to be the most effective, most trusted and self-sustaining humanitarian organisation in Kenya. MISSION Our mission is to work with vigor and compassion through our networks and with communities to prevent and alleviate human suffering and save lives of the most vulnerable. CORE VALUES t Commitment t Accountability t Service to Humanity t Trust VALUE PROPOSITION t Always There ǘ4ǚ ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2014 OUR FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES KRCS’s programmes and projects are designed and implemented according to the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement’s fundamental principles: HUMANITY To prevent and alleviate human suffering wherever it may be found. Our purpose is to protect life and health and ensure respect for the human being. KRCS promotes mutual understanding, friendship, cooperation and lasting peace amongst all people. IMPARTIALITY KRCS makes no discrimination as to nationality, race, religious beliefs, class or political opinions. It endeavours to relieve the suffering of individuals, being guided solely by their needs, and to give priority to the most urgent cases of distress. NEUTRALITY In order to continue to enjoy the confidence of all, the Red Cross Movement does not take sides in hostilities or engage at any time in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature. INDEPENDENCE The Movement is Independent. The national societies while auxiliaries in the humanitarian services of their Governments and subject to the laws of their respective countries, must always maintain their autonomy so that they are able at all times to act in accordance with the principles of the Movement. -

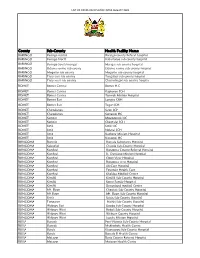

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface…………………………………………………………………….. i 1. District Context………………………………………………………… 1 1.1. Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 1 1.2. Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 1 2. Constituency Profile………………………………………………….. 1 Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 2.1. 1 Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 2.2. 1 Electioneering and Political Information……………………. 2.3. 2 1992 Election Results…………………………………………… 2.4. 2 1997 Election Results…………………………………………… 2.5. 2 Main problems……………………………………………………. 2.6. 2 3. Constitution Making/Review Process…………………………… 3 3.1. Constituency Constitutional Forums (CCFs)………………. 3 3.2. District Coordinators……………………………………………. 5 4. Civic Education………………………………………………………… 6 4.1. Phases covered in Civic Education…………………………… 4.2. Issues and Areas Covered……………………………………… 6 6 5. Constituency Public Hearings……………………………………… 7 5.1. Logistical Details…………………………………………………. 5.2. Attendants Details……………………………………………….. 7 5.3. Concerns and Recommendations…………………………….. 7 8 Appendices 31 1. DISTRICT PROFILE Busia District is one of 8 districts of the Western Province of Kenya. 1.1. Demographic Characteristics Male Female Total District Population by Sex 174,368 196,240 370,608 Total District Population Aged 18 years & 108,152 107,566 215,718 Below Total District Population Aged Above 18 66,216 88,674 154,890 years Population Density (persons/Km2) 330 1.2. Socio-Economic Profile Busia District: • Is one of the least densely populated districts in the province, being ranked 5th of the 8 districts in the province; -

A Model of HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment in a Rural Setting the Experiences of MSF in the Greater Busia District, Western Kenya 2000 – 2010 Nnon a N B Da © Bren

MSF April 2010 A Model of HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment in a Rural Setting The experiences of MSF in the Greater Busia District, Western Kenya 2000 – 2010 nnon A n B da © Bren Contents Acronyms (page 4) 1 Introduction (page 7) Letter from the Head of Mission 2 Summary (page 8) 3 Background (page 9) 4 Project Overview (page 10) 4.1 Voluntary Counselling and Testing 4.2 Antiretroviral Treatment & opportunistic Infections 4.3 Medical Supplies 4.4 Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission 4.5 Training & Mentorship 4.6 Community Activities 4.7 Monitoring and evaluation 4.8 networking and Collaboration 5 Impact (page 17) 6 Best Practices (page 24) 7 Handover of the Project (page 25) 8 Conclusions (page 26) 9 Recommendations (page 27) 9.1 Decentralization 9.2 Integration 9.3 Boost simplification 9.4 Free access for the treatment of oI’s and other services 9.5 Community involvement 9.6 Stability of funding Acronyms AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care ART Antiretroviral Treatment ARV Antiretroviral CAN Communication, Advocacy and networking CCC Comprehensive Care Centre CO Clinical officer DHMT District Health Management Team FDC Fixed Dose Combination GoK Government of Kenya HAART Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy HIV Human Immune Deficiency Virus HR Human resources HTC HIV Testing and Counselling IEC Information, education and Communication MoH Ministry of Health MSF Médecins sans Frontières MSF OCBA MSF operational Centre Barcelona Athens NASCOP national AIDS and STIs Control Programme NIMART nurse Initiated and Managed