Papers and Commentaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smash Hits Volume 34

\ ^^9^^ 30p FORTNlGHTiy March 20-Aprii 2 1980 Words t0^ TOPr includi Ator-* Hap House €oir Underground to GAR! SKias in coioui GfiRR/£V£f/ mjlt< H/Kim TEEIM THAT TU/W imv UGCfMONSTERS/ J /f yO(/ WOULD LIKE A FREE COLOUR POSTER COPY OF THIS ADVERTISEMENT, FILL IN THE COUPON AND RETURN IT TO: HULK POSTER, PO BOXt, SUDBURY, SUFFOLK C010 6SL. I AGE (PLEASE TICK THE APPROPRIATE SOX) UNDER 13[JI3-f7\JlS AND OVER U OFFER CLOSES ON APRIL 30TH 1980 ALLOW 28 DAYS FOR DELIVERY (swcKCAmisMASi) I I I iNAME ADDRESS.. SHt ' -*^' L.-**^ ¥• Mar 20-April 2 1980 Vol 2 No. 6 ECHO BEACH Martha Muffins 4 First of all, a big hi to all new &The readers of Smash Hits, and ANOTHER NAIL IN MY HEART welcome to the magazine that Squeeze 4 brings your vinyl alive! A warm welcome back too to all our much GOING UNDERGROUND loved regular readers. In addition The Jam 5 to all your usual news, features and chart songwords, we've got ATOMIC some extras for you — your free Blondie 6 record, a mini-P/ as crossword prize — as well as an extra song HELLO I AM YOUR HEART and revamping our Bette Bright 13 reviews/opinion section. We've also got a brand new regular ROSIE feature starting this issue — Joan Armatrading 13 regular coverage of the independent label scene (on page Managing Editor KOOL IN THE KAFTAN Nick Logan 26) plus the results of the Smash B. A. Robertson 16 Hits Readers Poll which are on Editor pages 1 4 and 1 5. -

<^ the Schreiber Times

< ^ The Schreiber Times Vol. XXVIII Paul D. Schreiber High School Wednesday, September 30, 1987 ZANETTI TAKES CHARGE Board Names Guidance Head as Acting Principal by Dave Weintraub When Dr. Frank Banta, Schreiber's principal for eight years, departed at the end (rf the last school year for a different job, he left some large shoes to fill. The school board and Superintendent Dr. William Heebink set out on a search for a new principal over the summer. Many applicants were reviewed, but no one was picked. The board and Dr. Heebink decided to extend the search through the 1987-88 school year. To fill the void Dr. Banta had left, they asked John Zanetti, Chairman of the Guidance Department, to serve as acting principal. He accepted, and was given a ten-month contract, which began in September. Most people who know Mr. Zanetti know him as a soft- spoken and amiable man. He has been in the Port Washington school system for many years, and he had humble beginnings. He started work at Salem School as a physical education teacher in 1958. He stayed there for six years and during that time in- troduced wrestling and lacrosse to the high school. He became the first coach of those teams. After Salem, he taught physical educa- tion at Schreiber for two years. He became a guidance counselor in 1967. He was appointed guidance chairman in 1980. He has now moved to the top of Schreiber's administrative lad- der. Has his transition been smooth? "I have an ulcer," he jokes. "Actually, I think I've ad- justed better than I thought I would. -

Difford & Tilbrook

Difford & Tilbrook Difford & Tilbrook mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Difford & Tilbrook Country: Europe Released: 1984 Style: New Wave MP3 version RAR size: 1704 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1629 mb WMA version RAR size: 1298 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 818 Other Formats: MPC AHX DXD FLAC MIDI MP1 APE Tracklist Hide Credits Action Speaks Faster A1 4:50 Arranged By [Brass] – Tony ViscontiBrass [Played By] – TKO Horns, The* Love's Crashing Waves A2 3:08 Arranged By [String Arrangements- Assisted] – Glenn Tilbrook Picking Up The Pieces A3 3:18 Arranged By [String Arrangements- Assisted] – Glenn Tilbrook A4 On My Mind Tonight 4:08 A5 Man For All Seasons 2:35 B1 Hope Fell Down 4:22 B2 Wagon Train 3:36 B3 You Can't Hurt The Girl 3:01 Tears For Attention B4 4:50 Producer – Chris Difford, E.T. Thorngren*, Glenn Tilbrook The Apple Tree B5 4:24 Mixed By – Tony Visconti Credits Arranged By [String Arrangements] – Tony Visconti (tracks: A2, A3, A5, B1) Art Direction, Design – Richard Frankel Backing Vocals – Debbie Bishop Bass – Keith Wilkinson Drums, Percussion – Andy Duncan Guitar, Vocals – Chris Difford Guitar, Vocals, Keyboards – Glenn Tilbrook Keyboards, Backing Vocals – Guy Fletcher Mastered By – Jack Skinner Percussion – Larry Tollfree* Photography By – Britain Hill Producer – Tony Visconti (tracks: A1 to B3, B5) Remix – E.T. Thorngren* Technician [Studio Assistance] – Bryan Robson , Chris Porter, George Chambers, Peter Notes Tracks: A1 to B3 & B5 produced at Good Earth Studios, London. Track: B5 mixed at Good Earth Studios, London. Track: B4 produced at Solid Bond, London. -

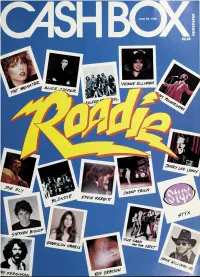

Cash Box Is Proud to Extend Its Congratulations to RICHARD IMAMURA, West Coast Editor MARK ALBERT

June 28, 1980 y^/VA/g" gLUtAAfJ i 0l tpvAc^. SEPTEMBER 26-30 MIAMI BEACH BAL HARBOUR AMERICANA HOTEL Roddy S. Shashoua President and Chairman USA HEADQUARTERS: International Music Industries, Ltd. 1414 Avenue of the Americas 6th Annual New York, New York 10019 U.S.A. Tel: (212) 489-9245' International Telex: 234107 Record/Video & Anne Stephenson Director of Operations ' Music Industry Market AUSTRALIA: FRANCE: General Public Relations Pty. Ltd. 18, avenue Matignon PO Box 451 75008 Paris, France Neutral Bay Junction 2089 Australia Tel: 622 5700 Tel: 9082411 Charles Ibgui, Telex: CLAUS AA26937 French Representative Harry Plant IF.YOU’RE IN THE Australian Representative UNITED KINGDOM: ITALY: MUSIC BUSINESS International Conferences & Via Correggio 27 Expositions Ltd. 20149 Milan, Italy 5 Chancery Lane, 4th Floor Tel: 482 456 YOU CAN’T AFFORD London WC2, England Tel: 404 0188/4567 Aldo Pagani, Telex: 896217 Roger THERE! G Italian Representative NOT TO BE - | . VOLUME XL1I — N HR 7 — June 28, 1980 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY DISH BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MEL ALBERT EDITORML Bright Future Ahead Vice President and General Manager NICK ALBARANO It Marketing Director A full year has passed since the Founder’s Con- Recording Merchandisers (NARM). has already ALAN SUTTON ference of the Black Music Assn. (BMA) kicked off begun to heighten public awareness through its Editor In Chief the inaugural celebration of June as Black Music programs. J.B. CARMICLE Month. In that time, the BMA has grown and Communication isthe key. If information can pass General Manager, East Coast matured, and on the eve of its second convention, freely and efficiently, great headway can be made in JIM SHARP Director. -

This Here... “...Sucked All the Creative Air out of the Rooms...” (H Waldrop)

ISSUE #14 This Here... “...sucked all the creative air out of the rooms...” (H Waldrop) into seeing this latest epic asap, especially given the good EGOTORIAL buzz surrounding it. But no, not in this case. I was vaguely reminded of my unwillingness to go see the original Star BB complains that we rarely sit and watch anything on TV Wars, in that case primarily because I was put off by the together (with the possible exceptions of TNA Wrestling, relentless hype. When The Empire Strikes Back came out, I which I’ve managed to get her into, and the local news at saw both in a special double feature at the local flick nearest dinner time). This isn’t really surprising, since when I’m to Tufnell Park, where I was then living, and reflected working (most of the time since September, but sadly not so afterwards that I was glad I hadn’t given in on the first one, much this month), I’m ready for bed around 8 since I get up since although I liked Empire a lot, the first one, eh, not so at 4am or so most days, and in any case whereas her taste much, since it suffers from the same problem as the later runs to whatever is on the Hallmark or Lifetime channels, Lord of the Rings epics, in that the central character, be it mine is an eclectic mix of rasslin’, MSNBC and Family Guy Frodo Baggins or Luke Skywalker, is an insufferable little tit. reruns. Overall I thought Nevertheless, the newest this Valentine’s incarnation of weekend I was Star Trek was persuaded to bloody good! I participate in the especially liked purchase of a the neat, if pay-per-view obvious movie for explanation for Saturday night, the continuity which is how I differences between this and finally got to see Spot the insufferable tit the J.J. -

How Jupiter Hit

INSIDE WEEK OF NOVEMBER 4-10, 2010 www.FloridaWeekly.com Vol. I, No. 4 • FREE How Jupiter SCOTT B. SMITH / FLORIDA WEEKLY 12 Angry Men hit the Plays through Nov. 14 at the Maltz Jupiter Theatre. C1 w biometricmotherload BY BILL CORNWELL bcornwell@fl oridaweekly.com Billion-dollar Scripps Florida Delivering on promises ROM THE BEGINNING, EXPECTATIONS for The Scripps Research Insti- seem almost to be setting the stage for a tute’s facility in Jupiter (known colossal letdown. Yet fervent believers as Scripps Florida) have been insist that not even the worst economic stratospheric. This should not meltdown since the Great Depression surprise, since supporters of can derail the ultimate success of the F the notion that South Florida ongoing Scripps Florida saga, which will Gardens Society in general — and Palm Beach County be played out over the next decade or so. in particular — can become an impor- See who's out and about in Few projects in Florida’s recent his- Palm Beach County. C13 &14 w tant player in the bioscience field on a tory have been so heavily promoted and national and international scale have extravagantly ballyhooed as Scripps Flor- done nothing to diminish or dampen ida, and few issues have stoked such pas- those lofty aspirations. sion and debate. The stakes, of course, At times, the breathless rhetoric are enormous. The state committed and titanic predictions of overwhelming success SEE SCRIPPS, A8 w Scripps Florida moved into its complex in Jupiter in 2009. Top fashion Trendy H&M arrives at The Ciao, amico! Largest state Italian fest on tap in Jupiter Gardens Mall. -

Squeeze Biog for Approval

It’s 1973 in South London. Teenage friends Chris Difford and Glenn Tilbrook form the band that will see them dubbed ‘The New Lennon and McCartney’. Over 35 years later, with their legacy intact and as vital as it has ever been, Squeeze are still touring and reminding fans worldwide just why they have left such an indelible impression on the UK’s music scene. As teenagers on the South London scene, Squeeze – setting out their stall early on by facetiously naming themselves after a poorly-received Velvet Underground album, and at the time also comprised of Jools Holland on keys, Harry Kakouli on bass and Paul Gunn on drums - became a fixture of the burgeoning New Wave movement. When Gilson Lavis replaced Gunn on drums everything seemed to fall into place, and word of mouth soon spread about the band - ironically, it was none other than Velvet Underground man John Cale who caught wind in 1977 and offered to produce their debut EP ‘Packet Of Three’ and much of the ensuing album. Yet it was second album ‘Cool For Cats’, released in 1979, which cemented their place as one of Britain’s most important young bands. Featuring the classic single ‘Up The Junction’ as well as the title track, it was many listeners’ first introduction to the witty kitchen-sink lyricism and new-wave guitar music that has become the band’s trademark. With albums ‘Argybargy’ and the Elvis Costello- produced ‘East Side Story’, Squeeze even started to make waves across the pond, although in 1980 former Roxy Music and Ace - and future Mike + The Mechanics – man Paul Carrack would replace Jools Holland, going on to lend his unmistakeable vocals to the smash hit ‘Tempted’. -

Greatest Hits Presss Release

1 THE BEST “BEST OF” ALBUM FROM POP HEROES SQUEEZE, ARTFULLY TITLED GREATEST HITS, MAKES ITS U.S. DEBUT There have been many retrospectives of pop’s acclaimed Squeeze but the one acknowledged as the best, and the only one combining the most popular A&M tracks from their New Wave tenure with their late ‘80s comeback hits, has not been available in the U.S. Now, Squeeze’s rightly named Greatest Hits (A&M/UME), released September 18, 2001, makes its Stateside debut. Spanning a decade of one of the best-loved bands of the ‘80s--the first band to star on “MTV Unplugged”--Greatest Hits (originally released in the U.K. in 1994 and previously available only as an import) features 20 selections from 1979 to 1989. Digitally remastered from the original master tapes, Greatest Hits brings together the dozen tracks from 1982’s platinum- certified Singles – 45s And Under with eight later selections. Highlighted are New Wave pop classics such as “Black Coffee In Bed,” “Tempted” (both with Paul Carrack on vocals), “Pulling Mussels (From The Shell)” and “Another Nail In My Heart” as well as Squeeze’s biggest U.S. hit, the Top 15 “Hourglass” (whose video was nominated as MTV’s Video of the Year). Also included are the U.K. Top 10s “Cool For Cats,” “Up The Junction,” “Labelled With Love” and “Take Me I’m Yours.” Singer-guitarist-songwriters Chris Difford and Glenn Tilbrook formed Squeeze in 1975 (singer-keyboardists Jools Holland and Carrack would join and exit more than once over their careers). -

Squeeze 6 Squeeze Songs Crammed Into One Ten-Inch Record Mp3, Flac, Wma

Squeeze 6 Squeeze Songs Crammed Into One Ten-inch Record mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: 6 Squeeze Songs Crammed Into One Ten-inch Record Country: US Released: 1979 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1860 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1503 mb WMA version RAR size: 1283 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 854 Other Formats: AUD MP4 VOC WMA DXD XM AU Tracklist A1 Goodbye Girl (Live Version) 2:49 A2 Cool For Cats (Single Version) 3:10 A3 Up The Junction (Remixed Single Version) 3:10 B1 Slap & Tickle 3:59 B2 Bang Bang 2:03 B3 Take Me I'm Yours 3:48 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – A&M Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – A&M Records, Inc. Published By – Deptford Songs Published By – Almo Music Corp. Pressed By – Fidelatone Mfg. Credits Art Direction, Design – Chuck Beeson Bass – Harry Kakoulli* (tracks: A2 to B3), John Bentley (tracks: A1) Cover [Concept] – Jeff Ayeroff* Drums – Gilson Lavis Illustration [Cover Illustration] – Cindy Marsh Keyboards – Jools Holland Lead Guitar, Keyboards, Vocals – Glenn Tilbrook Photography By [Group Photo] – George Du Bose* Photography By [Squeezed Cover Photo] – Mark Hanaur* Producer – John Wood (tracks: A2, A3), Squeeze Rhythm Guitar, Vocals – Chris Difford Written-By – Chris Difford, Glenn Tilbrook Notes Issued in a die-cut 12" sleeve designed to precisely accommodate a 10" record. The labels on some copies were slightly smaller than a standard LP to give the impression that the record was a 12" that had been shrunk. Track comments from sleeve: #A1: "GOODBYE GIRL. Recorded 'live' this version features Squeeze's new bass player, John Bentley, who replaced Harry Kakoulli in the Spring of 1979" #A2: "COOL FOR CATS. -

Sonny Rollins by John Ziegler

AIRWAVES A Service of Continuing Education and Extension - l5il University of Minnesota, Duluth VOL. I, NUMBER 7 MAY 1980 WDTH Staff Members Speak Out See page 1 1 COVER PHOTO: 1. Larry Peterson 2. Kevin Adams 3. Doug Nesheim 4. Mik Meyer 5. Phil Enke 6. Paul Schmitz 7. Bill Agnew 8. Tom Livingston 9. Craig Greening 10. Peter Petrachek 11. Stan Pollan 12. Stewart Holman 13. Gail Woitel 14. Cathe Hice 15. Jim Kellar 16. Don Rosacker 17. Dave Johnson 18. Julie Cameron · 19. Ellen Palmer 20. Doug Greenwood 21 . Ted Heinonen Comments from the Crew I started li stening to WDTH as a UMD In my one year of service at WDTH, I'm WDTH means music, good people, ex- student. I was never a real hard-core doing my part to clean up the airways of panding my ideas, expanding my interest listener as a student because I always had commercial radio which is destroying the in people, meeting new people to be so much else to keep me busy. A few fragile minds of young Americans. interested in. WDTH includes some weeks before I graduated, I decided to get Doug Greenwood people I truly love and will never give up involved, knowing I would have some as friends. WDTH means keeping my TV spare time after I finished school. I've off at home and not wearing out my To me, working at means being done several different shows both as a WDTH records. able to play what you want and not regular and a fill-in, and I now share having commercials every few minutes. -

CB-1980-04-12.Pdf

THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY YC-i.: z.-,3k GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MEL ALBERT Vice President and General Manager EDITORML Here To Serve NICK ALBARANO In better serve the music In addition, the chart identifies those records Marketing Director our continuing efforts to — below the Top 30 that have displayed exceptionally ALAN SUTTON industry, Cash Box has introduced a new feature Editor In Chief a comprehensive radio chart detailing airplay and strong action during the week. “PrimeMover” isthat KEN TERRY sales action for the Top 100 singles. Debuted in the record with the most radio activity; “Hit Bound” is Managing Editor March 29, 1980 issue, the Cash Box Radio Chart is the record with the most adds; and “Cash Smash” is J.B. CARMICLE General Manager. East Coast proving to be the most advanced radio program- the one with the strongest sales action. Altogether, JIM SHARP ming guide devised to date. these categories identify those records that are Director, Nashville moving up the charts the fastest. East Coast Editorial LEO SACKS — AARON FUCHS Not only does the chart detail which stations are It is our hope that this new chart will provide the RICHARD GOLD adding and jumping each record on a weekly basis, most accurate information upon which decisions Wes? Coast Editorial will RICHARD IMAMURA, Wesf Coast Editor it also notes which stations are day parting the hits. can be made. On a weekly basis, Cash Box strive MARK ALBERT, Radio Editor COOKIE AMERSON. Black Music Editor This information is tied in with any regional sales to provide current and precise data to aid the in- MARC CETNER — MICHAEL GLYNN DENNIS GARRICK — MICHAEL MARTINEZ patterns that emerge during the week, thus giving a dustry. -

The Comment, October 29, 1987

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University The ommeC nt Campus Journals and Publications 1987 The ommeC nt, October 29, 1987 Bridgewater State College Volume 65 Number 6 Recommended Citation Bridgewater State College. (1987). The Comment, October 29, 1987. 65(6). Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/comment/598 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The Comment Bridgewater State College October 29, 1987 Vol. LXV No. 6 Bridgewater, MA • Irving R. Levine speaks on economy By Bryon Hayes Graham-Rudman-Hollings Bill, own economies and the interest he said its objective was "to rates will increase. The Bridgewater State College steadily decrease the budget deficit Another point concerned the Lecture series presented its second until, in 1991, the budget will be United States trade deficit. In the guest speaker: Irving R. Levine, zero. If the President and 1980's, the U.S. has its largest Senior Economics Editor for Congress can not agree on the trade deficit in its history. One NBC News, in the Horace Mann way to do this, automatic cuts solution offered was to push Auditorium in Boyden Hall will be made across the board; in down the "strong dollar", to We.dne.sday. all programs - from military to allow American goods to be sold Levine began the discussion by social programs." The problem more, which would push up speaking on the economy, here, he explained, was the fact foreign goad's prices. But this mainly Wall Street and factors that the Democrats do not want has failed; the reasons being that which effect it.