[Post]Oedipai Fatherhood and Subjectivity in ABC's Lost "T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

'James Cameron's Story of Science Fiction' – a Love Letter to the Genre

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 27 - May 3, 2018 A S E K C I L S A M M E L I D 2 x 3" ad D P Y J U S P E T D A B K X W Your Key V Q X P T Q B C O E I D A S H To Buying I T H E N S O N J F N G Y M O 2 x 3.5" ad C E K O U V D E L A H K O G Y and Selling! E H F P H M G P D B E Q I R P S U D L R S K O C S K F J D L F L H E B E R L T W K T X Z S Z M D C V A T A U B G M R V T E W R I B T R D C H I E M L A Q O D L E F Q U B M U I O P N N R E N W B N L N A Y J Q G A W D R U F C J T S J B R X L Z C U B A N G R S A P N E I O Y B K V X S Z H Y D Z V R S W A “A Little Help With Carol Burnett” on Netflix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) (Carol) Burnett (DJ) Khaled Adults Place your classified ‘James Cameron’s Story Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 (Taraji P.) Henson (Steve) Sauer (Personal) Dilemmas ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End (Mark) Cuban (Much-Honored) Star Advice 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise (Wanda) Sykes (Everyday) People Adorable Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lisa) Kudrow (Mouths of) Babes (Real) Kids of Science Fiction’ – A love letter Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 to the genre for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light,3.5" ad “AMC Visionaries: James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction,” Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post premieres Monday on AMC. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Emmerson Denney

Toronto: 416.504.9666 EMMERSON DENNEY Vancouver: 604.744.0222 Los Angeles: 310.584.6606 PERSONAL MANAGEMENT Montreal: 1.888.652.0204 [email protected] TORONTO ••• VANCOUVER ••• LOS ANGELES www.emmerson.ca DIANE PITBLADO, B.A., M.F.A. (ACTRA/CAEA) Dialect/Voice Coach Film and Television American Gods Ricky Whittle Fremantle/David Slade Conviction Hayley Atwell ABC/ Liz Friedlander American Gothic Stephanie Leonidas CBS xXx: The Return… Donnie Yen Revolution/D.J. Caruso Suicide Squad Margot Robbie Warner Bros/David Ayres (plus Cara Delevingne; Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje) Defiance (season 3) Stephanie Leonidis Universal Secret Life of Marilyn… (miniseries) Kelli Garner, Emily Watson Lifetime/ Laurie Collyer Idol’s Eye (prep) Robert Pattinson Benaroya Pictures ROOM Brie Larson, Sean Bridgers Film4 Hannibal (Season 3) Mads Mikkelsen NBC/various God & Country Jake Croker Shaftesbury Films Aaliyah: Princess of R&B (MOW) Izaak Smith Lifetime/Bradley Walsh Regression lead cast Weinstein/Alejandro Amenábar (including Ethan Hawke; Emma Watson; David Dencik; Lothaire Bluteau) Bomb Girls (MOW) Tahmoh Penikett Muse The Girl King entire cast Galafilm-Triptych /Mika Kaurismäki (including Malin Buska; Sarah Gadon; Michael Nyqvist) Maps to the Stars (prep) Mia Wasikowska Prospero Pictures Hannibal (Season 2) Mads Mikkelsen NBC/various Hemlock Grove (Season 2) Dougray Scott Gaumont/various Defiance (Season 2) Stephanie Leonidis Universal Played (eps 111) Noam Jenkins; Liane Balaban Muse/Grant Harvey Pompeii lead cast FilmDistrict/Paul W.S. Anderson (including Emily Browning, Carrie-Anne Moss, Paz Vega, Sasha Roiz ) Saving Hope (eps 203) Raoul Baneja NBC/various Hannibal (Season 1) Mads Mikkelsen NBC/various Hemlock Grove (Season 1) Dougray Scott, Bill Skarsgard Gaumont/Eli Roth Defiance (Season 1) Stephanie Leonidis Universal Bomb Girls Tahmoh Penikett Muse/various XIII (eps 208) Camilla Scott Prodigy Pictures/Rachel Talalay Rewind (MOW) Keisha Castle-Hughes Universal Cable Resident Evil: Retribution (ADR) Li Bingbing Davis Films/Paul W.S. -

Tom Clancy’S “Patriot Games,” Released in 1992

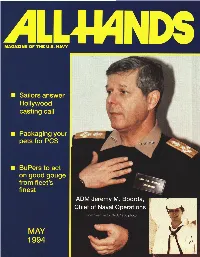

rn Packaging your ADM Jeremy .. Sa, Chief of Naval Operations From Seaman to CNO, 1956 photo D 4”r Any dayin the Navv J May 18,1994, is just like any other day in the Navy, butwe want you to photograph it. 0th amateur and professional civilian and military photographers are askedto record what's happening on their ship or installa- tion on Wednesday, May 18, 1994, for a special photo featureto appear in theOc- tober edition ofAll Hands magazine. We need photos that tell a story and capture fac-the es of sailors, Marines, their families and naval employ- ees. We're looking for imagination and creativity- posed shots will be screenedout. Shoot what is uniqueto your ship or installation, something you may see everyday but others may never get the opportunityto experience. formation. This includes full name, rank and duty sta- We're looking for the best photos from the field, for a tion of the photographer; the names and hometowns worldwide representation of what makes theNavy what of identifiable people in the photos; details on what's it is. happening in the photo; and where the photo tak- was Be creative. Use different lenses - wide angle and en. Captions must be attached individuallyto each pho- telephoto -to give an ordinaryphoto afresh look. Shoot to or slide. Photos must be processed and received by from different angles and don't be afraid to bend those All Hands by June 18, 1994. Photos will not be re- knees. Experiment with silhouettes and time-exposed turned. shots. Our mailing address is: Naval Media Center, Pub- Accept the challenge! lishing Division, AlTN: All Hands, Naval Station Ana- Photos must be shot in the 24-hour period of May costia, Bldg. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Nominations List 2006 Emmys

2006 Primetime Emmy Nominations Nominations 9 78th Annual Academy Awards American Masters Lost Six Feet Under Outstanding Casting For A Drama Series Big Love • HBO • Anima Sola and Playtone in association with HBO Entertainment Junie Lowry Johnson, C.S.A., Casting Director Libby Goldstein, Casting Director Boston Legal • ABC • David E. Kelley Productions in association with 20th Century Fox Television Studios Ken Miller, C.S.A., Casting by Nikki Valko, C.S.A., Casting by Grey’s Anatomy • ABC • Touchstone Television Linda Lowy, Casting by John Brace, Casting by House • FOX • Heel and Toe Productions, Shorez Productions and Bad Hat Harry Productions in association with Universal Television Studios Amy Lippens, C.S.A., Casting by Stephanie Laffin, Casting by Lost • ABC • Grass Skirt Productions, LLC in association with Touchstone Television April Webster, C.S.A., Casting by Veronica Collins Rooney, C.S.A., Casting by Mandy Sherman C.S.A., Casting by Outstanding Cinematography For A Single-Camera Series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation • Gum Drops • CBS • An Alliance Atlantis production in association with Paramount Television Michael Slovis, Director of Photography Everybody Hates Chris • Everybody Hates Funerals • UPN • Paramount Studios, 3Arts Entertainment, Chris Rock Enterprises, Inc. Mark Doering-Powell, Director of Photography Lost • Man Of Science, Man Of Faith • ABC • Grass Skirt Productions, LLC in association with Touchstone Television Michael Bonvillain, Director of Photography The Sopranos • The Ride • HBO • Chase Films and Brad -

Co-Workers Mourn, Address Elton's Murder

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELE RANSCRIPT ‘The Nerd’ sure T to keep THS theatre buffs in hysterics See B1 BULLETIN February 21, 2006 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 112 NO. 78 50 cents Many bills Co-workers mourn, address Elton’s murder unresolved Owners: no new policies needed as session by Jesse Fruhwirth STAFF WRITER nears end Fitting but surreal, the press conference was held across a by Jesse Fruhwirth pond from the Clearfield home STAFF WRITER where Raechale Elton was The Legislature is running out of raped and murdered. The for- time in its regular session, and many mer employers and co-workers of issues remain unresolved. The gover- the slain Tooele college student nor has locked horns with legislators spoke with the media Monday, over food and income taxes and radio- describing the last moments any- active waste disposal licensing. one would see her alive. Waste veto The owners of Youth Health Governor John Huntsman Jr. has Associates where Elton worked, promised to do what he can to stop and 17-year-old Robert Cameron SB-70, but legislators are only three Houston lived, said the victim votes from getting their way. The bill would have known her attack- allows the Legislature to override the er’s past criminal history, which governor’s veto in applications for included past sex crimes. They waste disposal licenses with a two- went on to describe the nature of thirds majority vote. their operations and how Elton That two-thirds vote is precisely found herself alone in a YHA- what the Legislature will need to over- owned home with her murderer. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

Bbc Weeks 51 & 52 19

BBC WEEKS 51 & 52 19 - 25 December 2015 & 26 December 2015 – 1 January 2016 Programme Information, Television & Radio BBC Scotland Press Office BBC Media Centre Scotland BBC iPlayer Scotland BBC Scotland twitter.com/BBCScotPR General / Carol Knight Hilda McLean Jim Gough Julie Whiteside Laura Davidson Karen Higgins BBC Alba Dianne Ross THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEK 51 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ SATURDAY 19 DECEMBER Not Another Happy Ending NEW BBC Two Scotland MONDAY 21 DECEMBER In Search of Gregor Fisher NEW BBC One Scotland TUESDAY 22 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland The Scots in Russia, Ep 1/3 NEW BBC Radio Scotland WEDNESDAY 23 DECEMBER The Big Yin, Ep 1/3 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Bothy Life - Bothan nam Beann NEW BBC Alba THURSDAY 24 DECEMBER – CHRISTMAS EVE Christmas Celebration NEW BBC One Scotland Nollaig Chridheil às a' Ghearasdan NEW BBC Alba The Christmas Kitchen NEW BBC Radio Scotland Watchnight Service NEW BBC Radio Scotland FRIDAY 25 DECEMBER – CHRISTMAS DAY Clann Pheter Roraidh NEW BBC Alba Christmas Morning with Cathy Macdonald and Ricky Ross NEW BBC Radio Scotland Get It On…at Christmas NEW BBC Radio Scotland A Lulu of a Kid NEW BBC Radio Scotland The Barrowlands NEW BBC Radio Scotland SATURDAY 26 DECEMBER – BOXING DAY Proms In The Park Highlights NEW BBC Two Scotland MONDAY 28 DECEMBER The Adventure Show NEW BBC Two Scotland Two Doors Down TV HIGHLIGHT BBC Two Trusadh - Calum's Music/Ceòl Chaluim