Instructed Eucharist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Praying with Body, Mind, and Voice

Praying with Body, Mind, and Voice n the celebration of Mass we raise our hearts and SITTING minds to God. We are creatures of body as well as Sitting is the posture of listening and meditation, so the Ispirit, so our prayer is not confined to our minds congregation sits for the pre-Gospel readings and the and hearts. It is expressed by our bodies as well. homily and may also sit for the period of meditation fol- When our bodies are engaged in our prayer, we pray lowing Communion. All should strive to assume a seated with our whole person. Using our entire being in posture during the Mass that is attentive rather than prayer helps us to pray with greater attentiveness. merely at rest. During Mass we assume different postures— standing, kneeling, sitting—and we are also invited PROCESSIONS to make a variety of gestures. These postures and gestures are not merely ceremonial. They have pro- Every procession in the Liturgy is a sign of the pilgrim found meaning and, when done with understand- Church, the body of those who believe in Christ, on ing, can enhance our participation in the Mass. their way to the Heavenly Jerusalem. The Mass begins with the procession of the priest and ministers to the altar. The Book of the Gospels is carried in procession to the ambo. The gifts of bread and wine are brought STANDING forward to the altar. Members of the assembly come for- Standing is a sign of respect and honor, so we stand as ward in procession—eagerly, attentively, and devoutly— the celebrant who represents Christ enters and leaves to receive Holy Communion. -

MORNING PRAYER 8:30 Am Prayer of Consecration (Canon of the Mass)

MORNING PRAYER 8:30 am Prayer of Consecration (Canon of the Mass) .......................................... BCP 80 Morning Prayer begins at the bottom of p. 6. The psalms for today are Psalms Our Father .................................................................................................. BCP 82 139 and 140, beginning on p. 514. The canticles after the lessons are the Te Prayer of Humble Access......................................................................... BCP 82 Deum, p. 10 and the Benedictus Dominus, p. 14. Fracture, Pax, Embolism & Agnus Dei (Hymnal Supplement 812) Holy Communion HOLY EUCHARIST Communion hymn (kneel), Coelites Plaudant ................... Hymnal 123 9:00 am This service follows the order of the 1928 Book of Common Prayer (page Communion sentence (Choir) O YE Angels of the Lord, bless ye the Lord : sing ye praises, and 67 and following) with Minor Propers from the Anglican Missal. magnify him above all for ever. 11:00 am Thanksgiving .............................................................................................. BCP 83 Postcommunion Collect Opening hymn, Quedlinburg .......................................................................... Insert O LORD, who seest that we do trust in the intercession of blessed Collect for Purity ......................................................................................... BCP 67 Michael thy Archangel : we humbly beseech thee ; that as we have Summary of the Law ................................................................................ -

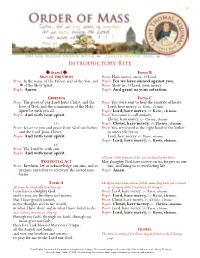

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

R.E. Prayer Requirement Guidelines

R.E. Prayer Requirement Guidelines This year in the Religious Education Program we are re-instituting Prayer Requirements for each grade level. Please review the prayers required to be memorized, recited from text, \understood, or experienced for the grade that you are teaching (see p. 1) Each week, please take some class time to work on these prayers so that the R.E. students are able not only to recite the prayers but also to understand what they are saying and/or reading. The Student Sheet (p. 2) will need to be copied for each of your students, the student’s name placed on the sheet, and grid completed for each of the prayers they are expected to know, or understand, or recite from text, or experience. You may wish to assign the Assistant Catechist or High School Assistant to work, individually, with the students in order to assess their progress. We will be communicating these prayer requirements to the parents of your students, and later in the year, each student will take their sheet home for their parents to review their progress. We appreciate your assistance in teaching our youth to know their prayers and to pray often to Jesus… to adore God, to thank God, to ask God’s pardon, to ask God’s help in all things, to pray for all people. Remind your students that God always hears our prayers, but He does not always give us what we ask for because we do not always know what is best for others or ourselves. “Prayer is the desire and attempt to communicate with God.” Remember, no prayer is left unanswered! Prayer Requirements Table of Contents Page # Prayer Requirement List……………………………………. -

Understanding the Mass: the Sign of the Cross, Greeting, and Introduction Why Do We Make the Sign of the Cross at Mass After

1 Understanding the Mass: The Sign of the Cross, Greeting, and Introduction Why do we make the sign of the cross at Mass after the procession, entrance chant, and the veneration of the Altar? In his book “What Happens at Mass,” Fr. Jeremy Driscoll O.S.B, writes, “A solemn and more meaningful beginning cannot be imagined.” 1 In thinking of the actual sign of the cross itself Fr. Driscoll explains, that, “the sign expresses the central event of our Christian faith. We trace it over our own bodies as a way of indicating that that event shall make its force felt on our bodies. The body on the Cross touches my body and shapes it for what is about to happen.” 2 Using the words “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit reveal the mystery of the Holy Trinity in the Death of Jesus on the Cross…at the very beginning of the Mass summarizes all that is about to happen.” 3 Fr. Driscoll points out the great commission from Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel quoting Jesus saying “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Matthew 28:16-20). Furthermore, Fr. Driscoll explains some of the words in the periscope. He writes ‘In the name’ could be more accurately put as ‘into the name.’ To baptize literally means ‘to dunk or plunge.’ Thus, the Christian is plunged into the name of God in Baptism. -

Why Do Lutherans Make the Sign of the Cross?

Worship Formation & Liturgical Resources: Frequently Asked Questions Why do Lutherans make the sign of the cross? The worship staff receives a number of similar inquires on worship-related topics from across the church. These responses should not be considered the final word on the topic, but useful guides that are to be considered in respect to local context with pastoral sensitivity. The response herein may be reproduced for congregational use as long as the web address is cited on each copy. "In the name of the Father, and of the + Son, and of the Holy Spirit” or “Blessed be the Holy Trinity, + one God, who forgives all our sin, whose mercy endures forever.” These words begin the orders for Confession and Forgiveness in Evangelical Lutheran Worship. The rubric (directions in red italics) that accompanies these words says: “The assembly stands. All may make the sign of the cross, the sign marked at baptism, as the presiding minister begins.” As this invocation is made, an increasing number of Lutherans trace the sign of the cross over their bodies from forehead to lower chest, then from shoulder to shoulder and back to the heart; and others trace a small cross on their foreheads. The sign of the cross, whether traced over the body or on the forehead, is a sign and remembrance of Baptism. The Use of the Means of Grace, The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s set of priorities for the practices of word and sacrament, says of this gesture: These interpretive signs proclaim the gifts that are given in the promise of God in Baptism…The sign of the cross marks the Christian as united with the Crucified (28A). -

New Traditions

THE MEMORIAL ACCLAMATION AMEN NEW TRADITIONS OCTOBER 14, 2018 THE LORD’S PRAYER 454 (Upper Room Worship Book, Chanted) THE TWEntIETH SUNDAY AFTER PEntECOST FRACTION ANTHEM 413 (Upper Room Worship Book) Agnus Dei BELL AGNUS PREACHING — REV. HILL CARMICHAEL RECEIVING THE BREAD AND CUP BY INTINCTION AND KNEELING LITURGIST — REV. SHERYL THORntON All are invited to receive Holy Communion. Ushers will guide you. CHOIRMASTER AND ORGANIST — DR. LESTER SEIGEL If your health requires you to avoid wheat products, gluten-free wafers are available on the paten behind the baptismal font. All are welcome to receive the sacrament. You do not have to be a member of Canterbury or of the United Methodist Church. It is the Lord’s table and all of God’s children are welcome. MUSIC DURING COMMUNION * PRAYER AFTER RECEIVING Eternal God, we give you thanks for this holy mystery in which you have given yourself to us. May we be transformed into your image. Grant that we may go into the world in the strength of your Spirit, to give ourselves for others, in the name of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. * BLESSING AND SENDING FORTH If you are visiting with us today, we are glad that you are here! You are always welcome at Canterbury. If you want more information about the ministries here, call Becky King at 871-4695 or email her at [email protected]. You can also check us out at www.canterburyumc.org. Encore Volunteer Training Tomorrow, October 15; 9:00 - 12:00 noon; Wesley Hall Encore enriches the lives of adults with memory loss through fellowship and activities, as well as supporting their families and caregivers. -

The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary

Alternative Services The Book of Alternative Services of the Anglican Church of Canada with the Revised Common Lectionary Anglican Book Centre Toronto, Canada Copyright © 1985 by the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada ABC Publishing, Anglican Book Centre General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada 80 Hayden Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4Y 3G2 [email protected] www.abcpublishing.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. Acknowledgements and copyrights appear on pages 925-928, which constitute a continuation of the copyright page. In the Proper of the Church Year (p. 262ff) the citations from the Revised Common Lectionary (Consultation on Common Texts, 1992) replace those from the Common Lectionary (1983). Fifteenth Printing with Revisions. Manufactured in Canada. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Anglican Church of Canada. The book of alternative services of the Anglican Church of Canada. Authorized by the Thirtieth Session of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada, 1983. Prepared by the Doctrine and Worship Committee of the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. ISBN 978-0-919891-27-2 1. Anglican Church of Canada - Liturgy - Texts. I. Anglican Church of Canada. General Synod. II. Anglican Church of Canada. Doctrine and Worship Committee. III. Title. BX5616. A5 1985 -

Holy Communion, Anglican Standard Text, 1662 Order FINAL

Concerning the Service Holy Communion is normally the principal service of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day, and on other appointed Feasts and Holy Days. Two forms of the liturgy, commonly called the Lord’s Supper or the Holy Eucharist, are provided. The Anglican Standard Text is essentially that of the Holy Communion service of the Book of Common Prayer of 1662 and successor books through 1928, 1929 and 1962. The Anglican Standard Text is presented in contemporary English and in the order for Holy Communion that is common, since the late twentieth century, among ecumenical and Anglican partners worldwide. The Anglican Standard Text may be conformed to its original content and ordering, as in the 1662 or subsequent books; the Additional Directions give clear guidance on how this is to be accomplished. Similarly, there are directions given as to how the Anglican Standard Text may be abbreviated where appropriate for local mission and ministry. The Renewed Ancient Text is drawn from liturgies of the Early Church, reflects the influence of twentieth century ecumenical consensus, and includes elements of historic Anglican piety. A comprehensive collection of Additional Directions concerning Holy Communion is found after the Renewed Ancient Text: The order of Holy Communion according to the Book of Common Prayer 1662 The Anglican Standard Text may be re-arranged to reflect the 1662 ordering as follows: The Lord’s Prayer The Collect for Purity The Decalogue The Collect of the Day The Lessons The Nicene Creed The Sermon The Offertory The Prayers of the People The Exhortation The Confession and Absolution of Sin The Comfortable Words The Sursum Corda The Sanctus The Prayer of Humble Access The Prayer of Consecration and the Ministration of Communion (ordered according to the footnote) The Lord’s Prayer The Post Communion Prayer The Gloria in Excelsis The Blessing The precise wording of the ACNA text and rubrics are retained as authorized except in those places where the text would not make grammatical sense. -

Global Christian Worship the Sign of the Cross

Global Christian Worship The Sign of the Cross http://globalworship.tumblr.com/post/150428542015/21-things-we-do-when-we-make-the- sign-of-the-cross 21 Things We Do When We Make the Sign of the Cross - for All Christians! Making ‘the sign of the cross’ goes back to the Early Church and belongs to all Christians. It’s a very theologically rich symbolic action! And did you know that Bonhoffer, practically a saint to Protestant Christians, often made the sign of the cross? (See below.) I grew up “thoroughly Protestant” and did not really become aware of “making the sign of the cross” in a thoughtful way until a few years ago, when I joined an Anglican church. Now it’s become a helpful act of devotion for me …. especially after I found this article by Stephen 1 Beale a few years ago (published online in November 2013) at http://catholicexchange.com/21-things-cross There is rich theology embedded in this simple sign, and as a non-Roman Catholic I appreciate all of the symbolism, and it does indeed deepen my spirituality and devotion. The history of making the symbolic motion goes back to the Early Church, more than a millennia before Protestants broke away in the Reformation. So when a Christian act has that long of a history, I believe that I can claim it for myself as a contemporary Christian no matter what denominations use it or don’t use it now. “Around the year 200 in Carthage (modern Tunisia, Africa),Tertullian wrote: ‘We Christians wear out our foreheads with the sign of the cross’ … By the 4th century, the sign of the cross involved other parts of the body beyond the forehead.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sign_of_the_cross So, here is a reposting of Stephen’s list, with additional resources at the end. -

11 A.M. the Holy Eucharist

Saint Mark’s episcopal cathedral seattle, washington live-streamed liturgy during cathedral closure The Holy Eucharist the third sunday of easter April 26, 2020 11:00 am Saint Mark’s episcopal cathedral seattle, washington live-streamed liturgy during cathedral closure To all members of the Saint Mark’s Cathedral community, and visitors and guests near and far, welcome to Saint Mark’s Cathedral’s livestream-only service of Holy Eucharist. The Book of Common Prayer reminds us that if one is unable to actually consume the consecrated bread and wine due to extreme sickness or disability, the desire is enough for God to grant all the benefits of communion (BCP, p. 457). When being present at a celebration of the Eucharist is impossible, this act of prayer and meditation can provide the means by which you can associate yourself with the Eucharistic Action and open yourself to God’s grace and blessing. Please join in singing the hymns, saying the responses, and participating in the prayers fully, even while unable to be present in the cathedral for a time. Please reach out to the cathedral—through whatever channel is convenient for you—to share what this experience was like for you, and how we might make it better. More information about the cathedral’s continuing activities during this time of closure may be found at saintmarks.org. 2 THE GATHERING A brief organ voluntary offered a few minutes before the hour invites all into quiet prayer and preparation. prelude Le Banquet Céleste [The Celestial Banquet] Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) welcome As the opening hymn is introduced, all rise as able. -

Third Edition of the Roman Missal 5 Minute Catechesis Segment 1 Introduction to the Roman Missal

THIRD EDITION OF THE ROMAN MISSAL 5 MINUTE CATECHESIS SEGMENT 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE ROMAN MISSAL This is the rst segment of brief catechetical presentations on the Third Edition of the Roman Missal. When presenting Segment 1 it will be helpful to have the Lectionary, the Book of the Gospels and the Sacramentary for display. Recommendations for use of these segments: • Presented by the pastor or other liturgical minister before the opening song of Mass • Incorporated into the homily • Put in the bulletin • Distributed as a handout at Mass • Used as material for small group study on the liturgy • Presented at meetings, music rehearsals, parish gatherings Outline of Segment One What is the Roman Missal? • Three main books: Lectionary, Book of the Gospels; Book of Prayers Why do we need a new missal? • New rites/rituals/prayers • New prayer texts for newly canonized saints • Needed clari cations or corrections in the text Translations • Missal begins with a Latin original • Translated into language of the people to enable participation • New guidelines stress a more direct, word for word translation • Hope to recapture what was lost in translation THIRD EDITION OF THE ROMAN MISSAL 5 MINUTE CATECHESIS SEGMENT 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE ROMAN MISSAL What is the Roman Missal and why are we are composed for use at the liturgy in which we going to have a new one? honor them. Secondly, as new rituals are developed or revised, such as the Rite of Christian Initiation of When Roman Catholics Adults, there is a need for these new prayers to be celebrate Mass, all included in the body of the missal, and lastly, when the prayer texts, the particular prayers or directives are used over time, readings from Scripture, it can become apparent that there is a need for and the directives that adjustment to the wording for clari cation or for tell us how Mass is to be accuracy.