Identification of Myth in the Propagation of Narrative Across Generational Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reverse Backstory Tool

REVERSE BACKSTORY TOOL Filling in this Reverse Backstory Tool for your characters will help you understand the big picture: what they want and need, what motivates them, what their backstories might be. Planning out their wounds and the lies they tell themselves will also help you choose what traits might help them succeed and which will get in the way. Plotting this information in the brainstorming stage (or even as you revise, to add depth to your character) will help you determine what sensitive areas to target, creating challenges for your hero. © Angela Ackerman & Becca Puglisi, 2013 1 http://writershelpingwriters.net PRAISE FOR THE EMOTION THESAURUS “One of the challenges a fiction writer faces, especially when prolific, is coming up with fresh ways to describe emotions. This handy compendium fills that need. It is both a reference and a brainstorming tool, and one of the resources I'll be turning to most often as I write my own books.” ~ James Scott Bell, best-selling author of Deceived and Plot & Structure PRAISE FOR THE POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE TRAIT THESAURUS BOOKS “In these brilliantly conceived, superbly organized and astonishingly thorough volumes, Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi have created an invaluable resource for writers and storytellers. Whether you are searching for new and unique ways to add and define characters, or brainstorming methods for revealing those characters without resorting to clichés, it is hard to imagine two more powerful tools for adding depth and dimension to your screenplays, novels or plays.” ~ Michael Hauge, Hollywood script consultant and story expert, author of Writing Screenplays That Sell and Selling Your Story in 60 Seconds: The Guaranteed Way to Get Your Screenplay or Novel Read © Angela Ackerman & Becca Puglisi, 2013 2 http://writershelpingwriters.net. -

Plot? What Is Structure?

Novel Structure What is plot? What is structure? • Plot is a series of interconnected events in which every occurrence has a specific purpose. A plot is all about establishing connections, suggesting causes, and and how they relate to each other. • Structure (also known as narrative structure), is the overall design or layout of your story. Narrative Structure is about both these things: Story Plot • The content of a story • The form used to tell the story • Raw materials of dramatic action • How the story is told and in what as they might be described in order chronological order • About how, and at what stages, • About trying to determine the key the key conflicts are set up and conflicts, main characters, setting resolved and events • “How” and “when” • “Who,” “what,” and “where” Story Answers These Questions 1. Where is the story set? 2. What event starts the story? 3. Who are the main characters? 4. What conflict(s) do they face? What is at stake? 5. What happens to the characters as they face this conflict? 6. What is the outcome of this conflict? 7. What is the ultimate impact on the characters? Plot Answers These Questions 8. How and when is the major conflict in the story set up? 9. How and when are the main characters introduced? 10.How is the story moved along so that the characters must face the central conflict? 11.How and when is the major conflict set up to propel them to its conclusion? 12.How and when does the story resolve most of the major conflicts set up at the outset? Basic Linear Story: Beginning, Middle & End Ancient (335 B.C.)Greek philosopher and scientist, Aristotle said that every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. -

Backstory-The Gospel Told As Story

BACKSTORY-THE GOSPEL TOLD AS STORY BACKSTORY LIFE@LARGE REVISITED Backstory is the new and revised version of Life@Large. We took all the best elements of the original version, simplified it, clarified it, and made it highly intuitive to use and wonderfuly visual to look at. The result is a very simple, very graphic, very clear presentation of the gospel message. Here is the opening premise: There are seven billion people in the world. Seven billion stories. And yet there are themes in our stories that are universal: betrayal, love, romance, redemption, sacrifice . The question is if there’s a larger story or narrative to which all our stories relate, one that makes sense of our shared experience—a common Back Story. The booklet goes on to explain the backstory which, of course, is the gospel: 1) Intimacy: God created us to know him 2) Betrayal: Humanity rebelled and sin seperated us from him 3) Anticipation: The Scriptures promise of a coming Deliverer 4) Pursuit: The coming of Christ 5) Sacrifice: Jesus’ death and resurrection 1 6) Invitation: God invites us to return to him 7) Reunion: The age to come—judgment and eternal life. As you can see, Backstory provides a broader more comprehensive BACKSTORY explanation of the gospel and thus a more compelling case for Christ. POSTCARDS FROM CORINTH ORDER ONLINE AT CRUPRESS.COM © 2010, CruPress, All Rights Reserved. CruPress.com HOW TO SHARE “BACKSTORY” 1. Read aloud the black pages, beginning with the “Does this prayer express the desire of your white text (the summary statements), followed by the heart?” If yes, ask if they’d like to pray the prayer right Bible passages. -

Academy of Television Arts & Sciences

ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ® GRAPHIC STANDARDS ©ATAS/NATAS TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 Our Logo Versus a Photograph of the Emmy® Award 5 Using the Television Academy and Emmy Name 6 The Television Academy Logo 7 Television Academy Logo Sizes 8 Logo Colors 9 More About the Logo 10 Whitespace Around the Logo 11 Text Wrap Around the Logo 12 Placement Examples 13-14 The Emmy as a Design Element 15 Cropping the Emmy 16-18 Television Academy Typefaces 19 Approvals 3 GRAPHIC STANDARDS The Television Academy is television. MANUAL The purpose of this Graphics Standards Manual is to set forth guidelines that will assist you in applying the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences logo to all communications including stationery, signage, mailings, invitations, advertising, brochures, motion graph- ics and online. Guided by the identity system presented here, you will be able to craft communications aligned with the Television Academy’s brand. Please note the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences only governs the Primetime Emmy® Awards. The Daytime, Sports and News Emmy Awards and International Emmys are governed from separate offices in New York. It is essential to maintain the integrity of the Television Academy’s identity through con- sistent implementation of this identity program across all applications. This identity is a graphic signature that enhances our image, reaffirms our relationships with constituents and increases awareness of our brand among the entertainment community at large. It conveys the organization’s core attributes and creates value in the marketplace. It is the primary symbol of the Television Academy’s brand and delivers the message that the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences stands for all that is great about television, the people who create it, and the cultural images it projects. -

Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel

Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel Edited by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel, Edited by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1732-5, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1732-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Madelena Gonzalez ................................................................................... vii Chapter One Generic Instability and the Limits of Postcolonial Identity Crossing Borders and Transforming Genres: Alain Robbe-Grillet, Edward Saïd, and Jamaica Kincaid Linda Lang-Peralta ...................................................................................... 2 Reading Nara’s Diary or the Deluding Strategies of the Implied Author in The Rift Marie-Anne Visoi...................................................................................... 11 Contaminated Copies: J.M.Coetzee’s -

The Bulletin of the Colloquium on Violence & Religion

The Bulletin of the Colloquium on Violence & Religion COV&R ____________________________________________________________________________________________ No. 45 October 2014 “THE ONE BY WHOM SCANDAL HAS COME” COV&R Object: “To explore, criti- cize, and develop the mimetic model of Critically Engaging the Girardian Corpus the relationship between violence and religion in the genesis and mainte- nance of culture. The Colloquium will be concerned with questions of both research and application. Scholars from various fields and diverse theo- retical orientations will be encouraged to participate both in the conferences and the publications sponsored by the Colloquium, but the focus of activity will be the relevance of the mimetic model for the study of religion.” The Bulletin is also available online: The Gateway Arch and city of St. Louis at night http://www.uibk.ac.at/theol/cover/bulletin/ COV&R Conference: July 8-12, 2015 at Saint Louis University Contents The Colloquium on Violence & Religion invites you to par- “The One by Whom Scandal Has Come” ticipate in its 25th Annual COV&R Conference. The theme COV&R Conference 2015 1 of the conference, “The One by Whom Scandal Has Come: Announcements 2 Critically Engaging the Girardian Corpus”, offers the oppor- Program of COV&R at the AAR 2014 3 tunity to look retrospectively at the relationship between mi- Letter from the President 4 metic theory and its critics in order to discuss constructively Musings from the Executive Secretary 5 the role these critiques have played in the development of -

Spontaneous Backstory Creation Ryan Sullivan Department Of

Spontaneous Backstory Creation Ryan Sullivan Department of Psychology and Neuroscience University of Colorado Boulder Defense Date: April 2, 2020 Thesis Advisor: Matt Jones Department of Psychology and Neuroscience Defense Committee: Matt Jones, Professor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience Eliana Colunga, Professor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience Paul Gordon, Professor of Humanities Abstract The ability to spontaneously construct narrative representations of others is an example of how predictive processing models can have implications for research in social cognition. In this study, subjects were given images or brief text excerpts of various people and asked to come up with a backstory for each. Responses were analyzed for length, structure, and source material. After analysis, cartoon images were found to elicit more evaluative clauses in their responses. Also, items that included text excerpts elicited responses that were of the narrative type most frequently. Subjects used people from their own lives as well as characters from fictional works as material when crafting their stories. The results of this study have implications for the study of fiction’s impact on cognition. Also, the neuroscience of such representations and clinical applications are discussed. Introduction Imagine you’re walking down a deserted street one afternoon when you see in the distance a man walking toward you with a strange, limping gait. It looks to you like he might be injured, so you walk a bit faster toward him to help. But a thought occurs to you that causes you to slow your step. Whatever injured him could still be there. It sort of looks like he’s trying to get away. -

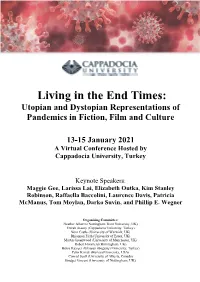

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

Play and Games in Fiction and Theory

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 11 | 2020 Are You Game? Play and Games in Fiction and Theory Joyce Goggin Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/2561 DOI: 10.4000/angles.2561 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference Joyce Goggin, « Play and Games in Fiction and Theory », Angles [Online], 11 | 2020, Online since 01 November 2020, connection on 13 November 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/angles/2561 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/angles.2561 This text was automatically generated on 13 November 2020. Angles est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Play and Games in Fiction and Theory 1 Play and Games in Fiction and Theory Joyce Goggin Introduction 1 There are many reasons to read fictional texts as a kind of play form or game. For example, popular works of fiction disseminated in various in media such as novels, TV series and films, frequently foreground their relationship to games with titles such as Game of Thrones (HBO 2011-2019), The Hunger Games (2012), or Molly’s Game (2018). But beyond a survey of titles, there are also more significant reasons for considering fiction and games together. Indeed, the history of literature is replete with examples of fictional texts structured around games, from Boccaccio’s Decameron (1353) and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (1392), to the game of Ombre in Pope’s Rape of the Lock (1712), to the preponderance of texts in various forms from print or codex to digital which have been published in the 20 th and 21 st centuries, and which somehow foreground their “game-ness”. -

Db:Scanner (Band)"Stephan O'mallie"@En"Maurycy "Mauser" Stefanowicz"@En "Wildeþrýð"@En Db:Nihilist (Band) "Dave Edwards"@En "Ashish Kumar"@Endb:Krieg (Band) "W.D

db:Amalie_Bruun "Dominik Immler"@en "Frater D."@en * Gunnar* Egill Þór* Birkir* Hafþór* Næturfrost "Simon O'Laoghaire"@en db:Kimmo_Heikkinen "Uri Zelcha"@en db:1349_(band) db:Dan-Ola_Persson "Itzik Levy"@en db:The_Kovenant "Zorugelion"@en "Derek MacAmhlaigh"@en db:Lord_Morbivod db:Zonata "Goran Paleka"@en "Johan Elving"@en "Damir Adžić"@en "Ines Tančeva"@en db:Alan_Averill "Elvorn"@en "Enrique Zúñiga Gomez"@en "Nick Oakes"@en db:Marcela_Bovio "Frank Calleja"@en "Miroslav Branković"@en "Maxime Aneca - Guitar"@en "*Lex Icon*Pzy-Clone*Hellhammer*Angel*Sverd"@en db:Alejandro_Mill%C3%A1n Ines Tan?eva "Cremator , Fermentor"@en Alejandro Díaz "MasterMike"@en "Maria "Tristessa" Kolokouri"@en "Martijn Peters"@en "Ivan Vasić"@en "Filip Letinić"@en "Eduardo Falaschi"@en A. db:Viathyn Bart Teetaert - Vocals "Lior Mizrachi"@en "Nikola Mijić"@en "Loke Svarteld"@en "Koen De Croo - Bass"@en "Chris Brincat"@en "Duke"@en db:The_Kovenant "Demian Tiguez"@en "*Tomislav Crnkovic*Dave Crnkovic*Jacob Wright*Alex Kot"@en "Fermentor Cremator , Fermentor"@en db:Lori_Linstruth Ivan Kutija "César Talarico"@en "Eden Rabin"@en db:Alex_Losbäck "Artyom"@en "Sami Bachar"@en "Marchozelos"@en "Morten"@en "* Wagner Lamounier* Roberto Raffan* Jairo Guedz* Max Cavalera* Igor Cavalera* Jean Dolabella"@en Lazar Zec - Guitar "Dave Hampton"@en "Wellu Koskinen"@en "VnoM"@en db:Sabbat_(Japanese_band) "* Christofer Johnsson* Thomas Vikström* Johan Koleberg* Nalle "Grizzly" Påhlsson* Christian Vidal* Lori Lewis"@en db:Arjen_Anthony_Lucassen "Mića Kovačević"@en "Roberto Raffan"@en db:Memnock db:Henrik_Carlsson db:Throllmas "Lazar Zec - Guitar"@en "Chris Calavrias"@enEric Hazebroek "Mathias"* PauloSchlegl"@en Jr.* Andreas Kisser* Derrick Green* Eloy Casagrande"@en"Yatziv Caspi"@en "Erkki Silvennoinen"@en "Gaahnt, Nattulv, Bahznar, Dermorh"@en "Marco Cecconi"@en Antti Kilpi "Gezol"@en Koen De Croo - Bass Elizabeth Toriser "Ze'ev Tananboim"@en db:Jukka_Kolehmainen J. -

Philosophy, Theory, Literature

PHILOSOPHY, THEORY, LITERATURE NEW & FORTHCOMING 20% DISCOUNT on all titles STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2015 Most SUP titles are available as e-books via our website or your favorite e-reading platform. Visit www.sup.org/ebooks for a complete list of offerings, as well as e-book rental and bundle options. TABLE OF CONTENTS Philosophy and Social Theory............................ 2-9 Literature, Criticism, and Literary Theory ............. 9-16 Art and Film ............................ 17-18 Pilate and Jesus Borrowed Light GIORGIO AGAMBEN Vico, Hegel, and the Colonies TRANSLATED BY ADAM KOTSKO Ordering Information .................2 TIMOTHY BRENNAN Pontius Pilate is one of the most Examination Copy Policy .......18 A critical revaluation of the humanist enigmatic figures in Christian the- tradition, Borrowed Light makes ology. The only non-Christian to be the case that the 20th century is the named in the Nicene Creed, he is “anti-colonial century.” The sparks of ORDERING presented as a cruel colonial overseer concerted resistance to colonial oppres- in secular accounts, as a conflicted Receive a 20% discount on all titles listed sion were ignited in the gathering of in this catalog. Use the following code to judge convinced of Jesus’s innocence intellectual malcontents from all over redeem this offer on hardcover and pa- in the Gospels, and as either a pious the world in interwar Europe. Many perback editions: S15LIT. Christian or a virtual demon in of this era’s principal figures were Please order by phone or online. Call later Christian writings. This book formed by the experience of revolution 800-621-2736 or visit www.sup.org. -

The Fever Dream of Documentary a Conversation with Joshua Oppenheimer Author(S): Irene Lusztig Source: Film Quarterly, Vol

The Fever Dream of Documentary A Conversation with Joshua Oppenheimer Author(s): Irene Lusztig Source: Film Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Winter 2013), pp. 50-56 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2014.67.2.50 Accessed: 16-05-2017 19:55 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Quarterly This content downloaded from 143.117.16.36 on Tue, 16 May 2017 19:55:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE FEVER DREAM OF DOCUMENTARY: A CONVERSATION WITH JOSHUA OPPENHEIMER Irene Lusztig In the haunting final sequence of Joshua Oppenheimer’s with an elegiac blue light. The camera tracks as she passes early docufiction film, The Entire History of the Louisiana a mirage-like series of burning chairs engulfed in flames. Purchase (1997), his fictional protagonist Mary Anne Ward The scene has a kind of mysterious, poetic force: a woman walks alone at the edge of the ocean, holding her baby in wandering alone in the smoke, the unexplained (and un- a swaddled bundle.