The Future Social Housing Provider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIM for Housing Associations

BIM for housing associations Asset management in the 21st century This joint project between leading associations and industry specialists seeks to enable housing associations large and small to learn from best practice and digitise development and asset information. Its outputs will provide an opportunity for associations to innovate and lead, showing the housing sector how to use Building Information Modelling (BIM) as a tool to deliver safer, better-managed buildings. Housing associations are among the nation’s largest property developers and landlords, some with £1bn development programmes. Regardless of size, they retain new assets and manage significant portfolios. The sector has led practical innovation by constructing according to the Code for Sustainable Homes and was among the first to address ACM cladding post Grenfell. Soon a new Building Safety Regulator will place challenging requirements on building owners to use a digital record to demonstrate buildings are safe to occupy. No other sector is so well positioned to lead the agenda to evidence safety as well as secure the cost and quality benefits. What is BIM? Building Information Modelling (BIM) isn’t just about 3D models or software. It’s about the managed scoping, production, checking and delivery of digital asset information, no matter what form it takes (models, reports, schedules etc), so that it can support the asset lifecycle. Image: Southern Housing Group / Child Graddon Lewis / Child Graddon Image: Southern Housing Group The Building Safety Regulator Legislation expected by spring 2021 will require the owners of residential buildings of over 18m or six storeys to thoroughly evidence that their buildings are safe. -

Landlords Moving Onto the UC Landlord Portal and Becoming Trusted Partners in 2017

Registered Social Landlords moving onto the UC Landlord Portal and becoming Trusted Partners in 2017 Landlord A2Dominion Homes Limited Accent Foundation Limited Adactus Housing Association Limited Affinity Sutton Homes Limited Aldwyck Housing Group Limited Angus Council Aster Communities B3 Living Limited Basildon District Council Bassetlaw District Council Birmingham City Council Boston Mayflower Limited bpha Limited Bracknell Forest Homes Limited Broadacres Housing Association Limited Bromford Housing Association Limited Catalyst Housing Limited Chesterfield Borough Council Circle Thirty Three Housing Trust Limited Coast and Country Housing Limited Coastline Housing Limited Community Gateway Association Limited Contour Homes Limited Cornwall Council Cottsway Housing Association Limited Cross Keys Homes Limited Curo Places Limited Devon and Cornwall Housing Limited Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council Dundee City Council East Durham Homes Limited East Thames EMH Homes (East Midlands Housing and Regeneration Limited) Family Mosaic Housing Festival Housing Limited Fife Council First Choice Homes Flagship Housing Group Limited Futures Homescape Limited Genesis Housing Association Limited Great Places Housing Association Greenfields Community Housing Gwalia Housing Group Hanover Housing Association Heart Of England Housing Association Helena Partnerships Limited Highland Council Home Group Limited Housing Solutions Limited Hyde Housing Association Limited Karbon Homes Limited Kirklees Metropolitan Borough Council Knightstone Housing Association -

From Gatekeepers to Gateway Constructors

Critical Perspectives on Accounting xxx (xxxx) xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Critical Perspectives on Accounting journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cpa From gatekeepers to gateway constructors: Credit rating agencies and the financialisation of housing associations ⇑ Stewart Smyth a, , Ian Cole b, Desiree Fields c a Sheffield University Management School, UK b Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR), Sheffield Hallam University, UK c Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley, US article info abstract Article history: This paper uses the twin metaphors of ‘gatekeeper’ and ‘gateway constructor’ as devices to Received 7 September 2017 explore the role of Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) as intermediaries between global Revised 10 July 2019 corporate finance and specific institutions – housing associations in England. The Accepted 11 July 2019 analysis utilises a financialisation framing, whereby the practices, logics and Available online xxxx measurements of finance capital, increasingly permeate government, institutional and household behaviour and discourse. This paper examines how housing associations have Keywords: increasingly resorted to corporate bond finance, partly in response to reductions in Financialisation government funding, and in the process engaged with CRAs. Social housing Credit rating agencies Surprisingly little research has been undertaken on the role and function of CRAs, and Corporate bonds their impact on the organisations they rate. The case of housing associations (HAs) is of particular interest, given their historical social mission to build and manage properties to meet housing need, rather than operate as commercial private landlords conversant with market-based rationales. A case study of the large London-based HAs draws on a narrative and financial analysis of annual reports, supplemented by semi-structured interviews with senior HA finance officers to explore how CRA methodologies have been internalised and have contributed to changes in strategic and operational activities. -

Organization A2dominion Housing Group Ltd Aberdeen Standard

Social Housing Annual Conference Thursday 9th November 200 Aldersgate, London EC1A 4HD. Sample delegate list (1 November 2017) T: +44 (0)207 772 8337 E: [email protected] Organization Job Title A2Dominion Housing Group Ltd Group Chief Exec Aberdeen Standard Investments Sales Director - Liquidity Solutions Aberdeen Standard Investments Institutional Business Development Manager Aberdeen Standard Investments Investment director, credit Accent Group Chief Executive Accent Group Executive Director of Finance & Corporate Services Al Bawardi Critchlow Managing Partner Aldwyck Housing Group Group Director of Finance Aldwyck Housing Group Group Chief Executive Aldwyck Housing Group Group chief executive Allen & Overy LLP Senior Associate Allen & Overy LLP Associate Allen & Overy LLP Consultant Altair Partner Altair Director Altair Director Altair Consultant Anchor Trust Financial Director Anthony Collins Solicitors LLP Partner Anthony Collins Solicitors LLP Partner Arawak Walton Housing Association Finance Director Arawak Walton Housing Association Deputy CEO and Executive Director, Resources ARK Consultancy Senior Consultant Assured Guaranty Director Aster Group Group chief executive Baily Garner LLP Partner Barclays Head of Social Housing, Barclays Barclays Relationship Director, Barclays Barclays Director, Barclays Barclays Director, Barclays PLC Bartra Capital Property CEO Black Country Housing Group Board Member BOARD Sector Lead – Commercial Property and Construction BOARD Business Development Manager Bond Woodhouse Managing -

A Step by Step Guide to Giving Security

A Step by Step Guide to Giving Security 1 Contents Page Introduction 3 Our Team 4 Team Profiles: 8 • London Office 8 • Colchester Office 12 • Leeds Office 15 Specialist team for smaller RPs and RSLs 17 Stress-free Securitisation 18 Securitisation Toolkit 19 Guide to Giving Security First Identify the Titles 20 Certificate of Title 21 Other Conditions Precedent 25 Pre-Completion Searches 26 Post-Completion Matters 27 Security Training 28 Suggested Timetable 29 Table of Confirmations 31 DEV1 Form 36 2 Introduction The purpose of this guide is to explain the legal process involved in charging properties as well as to provide practical tips to simplify the process and assist you to maximise the value of your property portfolio. We understand that the securitisation of your portfolio goes beyond just property charging. To assist with this, we have identified a number of key areas in this guide that we would recommend are reviewed as part of the overall securitisation process. We have also attached an indicative timetable setting out the necessary steps in order which can be tailored to our clients’ requirements. In our experience, it takes an average of twelve to sixteen weeks to charge a portfolio of properties with co-operation by Local Authorities. If you have any queries on this guide or would like a quote for acting for you on a charging exercise or are interested in any of the other services we have to offer, please contact Sharon Kirkham on 07932 105777 or [email protected] 3 Our Team: Sharon Kirkham Richard Sharpe Saghar -

Private Renting: Can Social Landlords Help? Anne Power, Alice Belotti, Laura Lane, Bert Provan

Private Renting: Can social landlords help? Anne Power, Alice Belotti, Laura Lane, Bert Provan CASEReport 113 January 2018 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ 5 Key Headlines ............................................................................................................................. 7 1. Private Renting – Can Social Landlords Help? .................................................................... 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 8 History .................................................................................................................................... 8 Post-War Boom ...................................................................................................................... 9 Government Changes Tack .................................................................................................. 10 Rebirth of Private Renting.................................................................................................... 12 Demographic and tenure change ........................................................................................ 12 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... -

Living a Life in Social Housing: a Report from the Real London Lives Project

Report to g15 Living a life in social housing: a report from the Real London Lives project Julie Rugg and Leonie Kellaher November 2014 Living a life in social housing Disclaimer Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the University of York, the Responsibility for any errors lies with the authors Copyright Copyright © University of York, 2014 All rights reserved. Reproduction of this report by photocopying or electronic means for non-commercial purposes is permitted. Otherwise, no part of this report may be reproduced, adapted, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without prior written permission of the Centre for Housing Policy, University of York. The Real London Lives research programme has been commissioned by g15. g15 represents London’s largest housing associations, providing homes for 1 in 10 Londoners and building a quarter of the capital’s new homes. We are working to solve the housing crisis by delivering good quality, affordable homes of all types. A core part of our role also involves initiating and delivering wide-ranging social and economic development activities in the communities where we work. The 15 comprises A2 Dominion Group, Affinity Sutton, Amicus Horizon, Catalyst Housing, Circle Group, East Thames Group, Family Mosaic, Genesis Housing Association, The Hyde Group, L&Q, Metropolitan, Network Housing Group, Notting Hill Housing, Peabody, Southern Housing Group. ISBN: 978-0-9929500-3-3 ii |Living a Life in Social Housing Living -

Trusted Partners

Universal Credit Trusted Partners Originally published: 03 October 2016 Latest update: 23 January 2018 (version 3) Contents Trusted Partners Applying for an alternative payment arrangement Ongoing support for the claimant Trusted Partners Trusted Partners are registered social landlords (including stock owning Local Authorities) that have made an agreement with DWP. They have agreed to support their tenants, where possible with financial and personal budgeting issues. In exchange they are allowed to request alternative payment arrangements (APAs) for their tenants whenever they identify a need. DWP will implement them without challenge. The following organisations are Trusted Partners: A1 Housing Bassetlaw LTD A2Dominion Homes Limited Accent Foundation Limited Adactus Housing Association Limited Affinity Sutton Homes Limited Aldwyck Housing Group Limited Alliance Homes (also listed as NSAH (Alliance Homes) Ltd) Angus Council Aster Communities B3 Living Limited Babergh & Mid Suffolk Basildon District Council Birmingham City Council bpha Limited Bracknell Forest Homes Limited Broadacres Housing Association Limited Bromford Housing Association Limited Cadwyn Cardiff Community Housing Association Cardiff Council Catalyst Housing Limited Chesterfield Borough Council Coast and Country Housing Limited Coastline Housing Limited Community Gateway Association Limited Contour Homes Limited Cornwall Housing Ltd (known as Cornwall Council) Cottsway Housing Association Limited Cross Keys Homes Limited Curo Places Limited -

On Site Units Recorded Between Jan-18 and Feb

Start on Site units recorded between Jan-18 and Feb-18 wth 10 or more units Reference: FOI MGLA 130618-4761 Notes: [1] Figures are provisional pending the publication of the GLA official statistics in August 2018. [2] Supported housing schemes have been redacted from the list Project title borough Lead_Organisation_Name dev_org_name planning_permission_ref SoS approval Total start Social Rent Other London Shared Other TBC erence date on sites (and LAR at Affordable Living Rent Ownership Intermedia benchmark Rent te s) Redacted Lewisham One Housing Group Limited One Housing Group Limited 30/01/2018 34 0 34 0 0 0 0 Redacted Lewisham One Housing Group Limited One Housing Group Limited 30/01/2018 19 0 0 0 19 0 0 Redacted Lambeth Network Housing Group Limited Network Housing Group Limited 05/01/2018 40 0 40 0 0 0 0 Redacted Tower Hamlets Islington and Shoreditch Housing Association Limited Islington and Shoreditch Housing Association Limited 02/01/2018 35 0 35 0 0 0 0 Chobham Manor, Newham Newham London & Quadrant Housing (L&Q) 24/01/2018 163 0 75 0 88 0 0 County House - LLR Bromley Hyde Housing Association Limited 29/01/2018 76 0 0 76 0 0 0 Doncaster Drive Ealing London Borough of Ealing 31/01/2018 10 0 0 0 10 0 0 1 Station Square Haringey Newlon Housing Trust HGY/2016/3932 24/01/2018 117 0 0 0 117 0 0 Gallions Phase 1 Newham Notting Hill Housing Trust 14/00664/OUT 29/01/2018 165 4 38 50 73 0 0 Cannons Wharf Lewisham London & Quadrant Housing (L&Q) 30/01/2018 84 0 22 0 62 0 0 Royal Wharf Phase 4 Newham Notting Hill Housing Trust 15/00577/VAR -

London Traditional Housing Associations & LSVT Value For

Appendix 2 – London Traditional Housing Associations & LSVT Key: Upper Quartile, Middle Upper Quartile, Middle Lower Quartile, Lower Quartile Value for money summary Efficiency Summary for Brent Housing Partnership Cost KPI Quartile Quality KPI Quartile Business Cost KPI Brent Brent Quality KPI Brent Brent Activity Housing Housing Housing Housing Partnership Partnership Partnership Partnership (2011/2012) (2010/2011) (2011/2012) (2010/2011) Overhead costs as % Overhead costs as % direct revenue Overheads adjusted turnover costs Percentage of tenants satisfied with Major Works Total CPP of Major overall quality of home (GN & HfOP) & Cyclical Works & Cyclical Maintenance Maintenance Percentage of dwellings failing to meet the Decent Homes Standard Percentage of tenants satisfied with the repairs and maintenance service (GN & HfOP) Responsive Total CPP of Repairs & Responsive Repairs & Percentage of all repairs completed Void Works Void Works on time Average time in days to re-let empty properties Percentage of tenants satisfied with overall services provided (GN & HfOP) Housing Total CPP of Housing Percentage of tenants satisfied that views are being taken into account Management Management (GN & HfOP) Current tenant rent arrears net of unpaid HB as % of rent due Percentage of residents satisfied with quality of new home, surveyed Staff involved in standard units within 3 years of completion Development developed per 100 units Standard units developed as % of current stock Percentage of tenants satisfied with Estate Total CPP of Estate -

Vendor £ THAMES WATER UTILITIES LTD 503.24 TIPPERHIRE LTD

Vendor £ THAMES WATER UTILITIES LTD 503.24 TIPPERHIRE LTD 506.00 CAREQUALITY COMMISION 509.80 PESH FLOWERS 510.50 HOPE EDUCATION LTD 518.72 STANLEY PRODUCTIONS LTD 519.50 BEDE CAFE PROJECT 520.00 NDY CONSULTING LTD 520.00 ARBORTECH TREE TECHNOLOGY LTD 522.42 EDMUNDSON ELECTRICAL LTD 525.86 CEAMD LTD 526.42 HENRY SHEACH LAWNMOWER SER LTD 528.93 FLEURETS CHARTERED SURVEYORS 532.60 AGGORA (EQUIPMENT) LTD 536.50 BOURNE AMENITY LTD 540.00 SUMI RATNAM & CO LTD 540.00 PENNINGTON CHOICE 541.67 ANDREW WALLER 549.00 HBAHRA CONSULTANCY LIMITED 550.00 HOME OFFICE LEAVE TO REMAIN 550.00 MOUNT CARMEL LTD 555.10 ANGEL HUMAN RESOURCES 559.24 ADVANCE SEATING DESIGNS 562.30 I-SOURCEIT LIMITED 562.50 THE TOPP PARTNERSHIP LTD 566.05 VIAJES 569.34 SIGNSCAPE SYSTEMS LTD 570.18 GOLF & TURF EQUIPMENT LTD 570.55 PAC GRAPHIC LIMITED 580.00 EXPERIAN LTD 580.48 SAFECARE SERVICES LTD 585.00 P J BINGHAM & CO LTD 590.00 KINGS COLLEGE HOSPITAL NHS TRUST 593.21 MSSRS ARNOLD & PORTER (UK) LLP 595.84 QUEEN MARY AND WESTFIELD COLLEGE 595.90 ASTRAL LODGE CARE HOME 598.40 KENILWORTH HOUSE NURSING HOME 598.40 ABWOOD CONTRACT SUPPORT LIMITED 600.00 ASQUITH COURT HOLDINGS 600.00 FOUNDATION 4 LIFE (LLP) 600.00 FRAMA (UK) LTD 600.00 REDINGTON CONSULTANCY LTD 600.00 URBIS LIGHTING LTD 602.10 RICOH CAPITAL LTD 603.46 SUPERTEC DESIGNS LTD 610.00 THE SEWING CENTRE 619.50 THE UNIVERSITY OF GREENWICH 620.00 LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM 621.84 FRAMA (UK) LTD 621.97 LOOKING AHEAD HOUSING AND CARE 622.72 UNIQUE HELP LTD-CHESTERFIELD HOUSE 623.07 RESPOND 625.00 K & O CHILDCARE LTD 628.65 KEY TRAFFIC SYSTEMS LTD 630.00 HSBC INVOICE FINANCE (UK) LIMITED 633.16 LONDON GRID FOR LONDON 638.33 DYASON PRE-SCHOOL 641.50 CLEANOVATION 643.34 GLENTHURSTON HOLIDAY APARTMENTS 645.00 EAST THAMES GROUP 648.48 DARTFORD METALCRAFTS 650.00 SUTTON WINDOWS LTD 650.00 ZETA HOMES LTD 650.00 CHARTERED INST. -

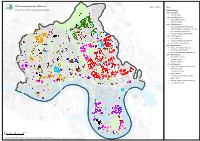

RLS Housing More Than 1000 Units Bur R Oa Date: 17/04/2013 E D Key a S T

C arp en Ro oad te th y R rs RLS Housing more than 1000 units bur R oa Date: 17/04/2013 E d Key a s t C r AF221773PD - GIS for Development and Renewal o s s RSL Housing R o u XW t 7001> Properties X e XW X POPLAR HARCA X X X X X 3001 - 4000 Properties XXX XY X XX X X X X X X ONE HOUSING GROUP XX X X XXY XXWX X XX XX X XX XXXXX X EAST END HOMES XX X X XX XX XX X XX XXX XW X XX X XX X X X X XX 2001- 3000 Properties X XWX X XX X X XXX XX XX X X X X X XXXX X X X XY XWX X X X XW XWXY XW X OLD FORD HOUSING ASSOCIATION X X X X XW X XX X X XW XW XX X XY X XX XW X TOWER HAMLETS COMMUNITY HOUSING X X XX X XWX X X X X XX XY XW XW X XY X XX X XW X XW XWXWXW XY XY X XY SWAN HOUSING ASSOCIATION X XW X XX X X X XYXY X X X XW XXX XY XY X XY ad X X XXX X XY X X XW Hackney Ro X X XWXY XXX XW X X GATEWAY HOUSING ASSOCIATION XX X X X XW X XXW XW X X X XX XY X X X X XXX X X X XWXW XW XW X XW XX X X X XX X X X XYX X XXW XY XYXW XW X X X X X X XY X XW X X XY 1001 - 2000 Properties XY X XW XW XW X XY X X X XW X X X XWXXW XY X X X X X X X G XW XY X X X X EAST HOMES HA X X r XW X X X X o XW d X X X vX X oa X X X X e XY w R X X X XW XW X Bo X X XX XW X X X R X XY X XY X X X XWo XW XXW X X GENESIS HOUSING ASSOCIATION XW XXYX X a XW XW X X X XW d X XXW XW X X X X XYXY XY X XWXX XW S XW X X XW XW X X h X X oad X XW XW X XY X o X SOUTHERN HOUSING GROUP XW Xreen R XY XW XY X X XY X r nal G XW XY X X X e Beth XW X X X XX X X XY d XW X X X XX XYX X XY i XY X X t X X X X XX XW c XW XW XY XW X X 501 - 1000 Properties h XW X X X X X X X XW XY X X X X H X XY XXYX XX X i g