The Long Take in Modern European Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kvarterakademisk

kvarter Volume 18. Spring 2019 • on the web akademiskacademic quarter From Wander to Wonder Walking – and “Walking-With” – in Terrence Malick’s Contemplative Cinema Martin P. Rossouw has recently been appointed as Head of the Department Art History and Image Studies – University of the Free State, South Africa – where he lectures in the Programme in Film and Visual Media. His latest publications appear in Short Film Studies, Image & Text, and New Review of Film and Television Studies. Abstract This essay considers the prominent role of acts and gestures of walking – a persistent, though critically neglected motif – in Terrence Malick’s cinema. In recognition of many intimate connections between walking and contemplation, I argue that Malick’s particular staging of walking characters, always in harmony with the camera’s own “walks”, comprises a key source for the “contemplative” effects that especially philo- sophical commentators like to attribute to his style. Achieving such effects, however, requires that viewers be sufficiently- en gaged by the walking presented on-screen. Accordingly, Mal- ick’s films do not fixate on single, extended episodes of walk- ing, as one would find in Slow Cinema. They instead strive to enact an experience of walking that induces in viewers a par- ticular sense of “walking-with”. In this regard, I examine Mal- ick’s continual reliance on two strategies: (a) Steadicam fol- lowing-shots of wandering figures, which involve viewers in their motion of walking; and (b) a strict avoidance of long takes in favor of cadenced montage, which invites viewers into a reflective rhythm of walking. Volume 18 41 From Wander to Wonder kvarter Martin P. -

Kenji Mizoguchi Cinematographic Style (Long Take) in 'The Life of Oharu' (1952)

KENJI MIZOGUCHI CINEMATOGRAPHIC STYLE (LONG TAKE) IN 'THE LIFE OF OHARU' (1952). Rickmarthel Julian Kayug Bachelor ofApplied Arts with Honours (Cinematography) 2013 UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SARAW AK BORANG PENGESAHAN STATUS TESIS/LAPORAN JUDUL: Kenji Mizoguchi Cinematographic Style (Long Take) In The 'Life OfOharu' (1952). SESI PENGAJIAN: 200912013 Saya RICKMARTHEL JULIAN KA YUG Kad Pengenalan bemombor 890316126011 mengaku membenarkan tesisl Laporan * ini disimpan di Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dengan syarat-syarat kegunaan seperti berikut: 1. Tesisl Laporan adalah hakmilik Universiti Malaysia Sarawak 2. Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dibenarkan membuat salinan untuk tujuan pengajian sahaja 3. Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dibenarkan membuat pengdigitan untuk membangunkan Pangkalan Data Kandungan Tempatan 4. Pusat Khidmat Maklumat Akademik, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak dibenarkan membuat salinan tesisl laporan ini sebagai bahan pertukaran antara institusi pengajian tinggi 5. *sila tandakan rn (mengandungi maklumat yang berdarjah keselamatan SULIT 6·D atau kepentingan seperti termaktub di dalam AKTA RAHSIA 1972) TERHAD D (mengandungi maklumat Terhad yang telah ditentukan oleh Organisasilbadan di mana penyelidikan dijalankan) V ~IDAK TERHAD Disahkan Disahkan Oleh: c:dt~f • Tandatangan Penulis Tandatangan Penyelia Tarikh t:L~ 1"""~ ~ l3 Tarikh: '~I O-=l""/?4l ~ Alamat Tetap: Kg. Pamilaan, Peti Surat 129,89908 Tenom, Sabah. Mobil Jefri ~ samareoa Lect\Il'U . faculty ofApplie4 aM CrcallVe Catatan: *Tesis/ Laporan dimaksudkan sebagai tesis bagi Ijazah Doktor Falsafah,~a Muda • lika Tesis/ Laporan SULIT atau TERHAD, sila lampirkan surat daripada pihak berkuasal organisasi berkenaan dengan menyatakan sekali sebab dan tempoh tesis/ laporan ini perlu dikelaskan $ebagai SULIT atau TERHAD This project report attached hereto, entitled "KENJI MIZOGUCHI CINEMATOGRAPHIC STYLE (LONG TAKE) IN THE LIFE OF OHARU (1952)". -

Download English-US Transcript (PDF)

MITOCW | watch?v=ftrKlCmELm4 The following content is provided under a Creative Commons license. Your support will help MIT OpenCourseWare continue to offer high quality educational resources for free. To make a donation or to view additional materials from hundreds of MIT courses, visit MIT OpenCourseWare at ocw.mit.edu. PROFESSOR: I want to talk a little bit about producing and realizing your visions, and give an example of some of the things that Chris was talking about. So we shot a video on how engines worked, and there is a part of the video where the two creators were talking about how a turbine engine works. And I think I might have told this story before, about how we ended up finding like an actual Boeing engine. But there are a lot of ways that we could have filmed this scene. We could have animated it, we could have done a wide frame shot with animation overlay, like I showed you with George's [INAUDIBLE] videos. We could have done B-roll, so we could have just done like close up shots of the engine while you heard Luke explaining how it worked, with his voiceover. Or we could have done a live explanation, which is what we went with. So this is how George shot Luke. We went with the traditional thirds framing. Again, this isn't necessarily a rule that you have to go by, it just worked really well for this scene. And we went with this because it also gave us the ability to do sort of an interesting point of view shot. -

COPYRIGHTED by RUTH BELI, GOBER 1957

COPYRIGHTED by RUTH BELI, GOBER 1957 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE AMERICAN NOVELIST INTERPRETS THE STUDENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION BY RUTH BELL GOBER Norman, Oklahoma 1956 THE AMERICAN NOVELIST INTERPRETS THE STUDENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION APPROVED BY ÎSIS COMMITTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION..................................... 1 II. F. SCOTT FITZGERALD.............................. 8 III. WILLA CATHER..................................... 46 IV. SINCLAIR LEWIS........................ 68 V, GEORGE SANTAYANA................................. Il8 VI. THOMAS WOLFE..................................... 142 VII. FINDINGS.......................................... 191 BIBLIOGRAPHY.............................................. 204 iv THE AMERICAN NOVELIST INTERPRETS THE STUDENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION "For a century and a half, the novel has been king of 1 Western literature." It has both mirrored and influenced popular thought as it has found readers throughout the West ern world. "The drama and the poetry, but chiefly the novel, of America have risen to a position of prestige and of influ- 2 ence abroad seldom equaled in history." Consequently, the content of the novel is of concern to educators. The present study is concerned with the interpretation of the student of higher education in the United States as found in the work of certain prominent American novelists of the twentieth century. The procedure used in selecting the five literary writers included an examination of annotated bibliographies of the American novels published during the twentieth century. The formidable number of writers who have used student 1------------------------------------------------------------- Henri Peyre, The Contemporary French Novel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955]> 3. ^Ibid., 263. -

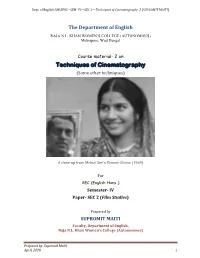

Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI)

Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) The Department of English RAJA N.L. KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Midnapore, West Bengal Course material- 2 on Techniques of Cinematography (Some other techniques) A close-up from Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) For SEC (English Hons.) Semester- IV Paper- SEC 2 (Film Studies) Prepared by SUPROMIT MAITI Faculty, Department of English, Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College (Autonomous) Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. April, 2020. 1 Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) Techniques of Cinematography (Film Studies- Unit II: Part 2) Dolly shot Dolly shot uses a camera dolly, which is a small cart with wheels attached to it. The camera and the operator can mount the dolly and access a smooth horizontal or vertical movement while filming a scene, minimizing any possibility of visual shaking. During the execution of dolly shots, the camera is either moved towards the subject while the film is rolling, or away from the subject while filming. This process is usually referred to as ‘dollying in’ or ‘dollying out’. Establishing shot An establishing shot from Death in Venice (1971) by Luchino Visconti Establishing shots are generally shots that are used to relate the characters or individuals in the narrative to the situation, while contextualizing his presence in the scene. It is generally the shot that begins a scene, which shoulders the responsibility of conveying to the audience crucial impressions about the scene. Generally a very long and wide angle shot, establishing shot clearly displays the surroundings where the actions in the Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. -

Memory, History, and Entrapment in the Temporal Gateway Film

Lives in Limbo: Memory, History, and Entrapment in the Temporal Gateway Film Sarah Casey Benyahia A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Department of Literature, Film, and Theatre Studies University of Essex October 2018 Abstract This thesis examines the ways in which contemporary cinema from a range of different countries, incorporating a variety of styles and genres, explores the relationship to the past of people living in the present who are affected by traumatic national histories. These films, which I’ve grouped under the term ‘temporal gateway’, focus on the ways in which characters’ experiences of temporality are fragmented, and cause and effect relationships are loosened as a result of their situations. Rather than a recreation of historical events, these films are concerned with questions of how to remember the past without being defined and trapped by it: often exploring past events at a remove through techniques of flashback and mise-en-abyme. This thesis argues that a fuller understanding of how relationships to the past are represented in what have traditionally been seen as different ‘national’ cinemas is enabled by the hybridity and indeterminacy of the temporal gateway films, which don’t fit neatly into existing categories discussed and defined in memory studies. This thesis employs an interdisciplinary approach in order to draw out the features of the temporal gateway film, demonstrating how the central protagonist, the character whose life is in limbo, personifies the experience of living through the past in the present. This experience relates to the specifics of a post-trauma society but also to a wider encounter with disrupted temporality as a feature of contemporary life. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Beil & Howell Iniormation Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313,761-4700 800,521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

The General Idea Behind Editing in Narrative Film Is the Coordination of One Shot with Another in Order to Create a Coherent, Artistically Pleasing, Meaningful Whole

Chapter 4: Editing Film 125: The Textbook © Lynne Lerych The general idea behind editing in narrative film is the coordination of one shot with another in order to create a coherent, artistically pleasing, meaningful whole. The system of editing employed in narrative film is called continuity editing – its purpose is to create and provide efficient, functional transitions. Sounds simple enough, right?1 Yeah, no. It’s not really that simple. These three desired qualities of narrative film editing – coherence, artistry, and meaning – are not easy to achieve, especially when you consider what the film editor begins with. The typical shooting phase of a typical two-hour narrative feature film lasts about eight weeks. During that time, the cinematography team may record anywhere from 20 or 30 hours of film on the relatively low end – up to the 240 hours of film that James Cameron and his cinematographer, Russell Carpenter, shot for Titanic – which eventually weighed in at 3 hours and 14 minutes by the time it reached theatres. Most filmmakers will shoot somewhere in between these extremes. No matter how you look at it, though, the editor knows from the outset that in all likelihood less than ten percent of the film shot will make its way into the final product. As if the sheer weight of the available footage weren’t enough, there is the reality that most scenes in feature films are shot out of sequence – in other words, they are typically shot in neither the chronological order of the story nor the temporal order of the film. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Cinema of Theo Angelopoulos Edited by Angelos Koutsourakis & Mark Stevens Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015

FILMICON: Journal of Greek Film Studies ISSUE 4, December 2017 BOOK REVIEW The Cinema of Theo Angelopoulos edited by Angelos Koutsourakis & Mark Stevens Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015 Thanassis Vassiliou Université de Poitiers The collective volume The cinema of Theo Angelopoulos, edited by Angelos Koutsourakis and Mark Stevens, attempts to establish and highlight the reasons why the cinema of Theo Angelopoulos holds a very important position in the history of world cinema. The book comprises seventeen essays and is divided in four complementary parts: authorship, politics, poetics, and time. In the introduction of the book, discussion revolves around whether Theo Angelopoulos’s work, which starts in the late 1960s, can be interpreted through the prism of late-modernism as the oeuvre of one of the many significant directors who proved that cinema becomes universal when is deeply anchored in the traditions and the history of its country of origin. This, however, cannot be perceived only in positive terms. The critical reception of Angelopoulos’s work was often uneasy about the fact that his films are deeply imbricated in modern Greek history (p. 9). This uneasiness was further increased by the fact that Angelopoulos was always considered as a living anachronism. The editors aptly juxtapose the question of the position of Angelopoulos’s work in modern cinema with its critical reception, and before they pass the torch to the contributing authors, they make sure to offer a short synopsis of modern Greek history, necessary to the unacquainted readers. Ι. Authorship The five texts comprising the first part of the book approach Angelopoulos’s work through his formation as an author. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Advertising "In These Imes:"T How Historical Context Influenced Advertisements for Willa Cather's Fiction Erika K

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: English, Department of Department of English Spring 5-2014 Advertising "In These imes:"T How Historical Context Influenced Advertisements for Willa Cather's Fiction Erika K. Hamilton University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the American Literature Commons Hamilton, Erika K., "Advertising "In These Times:" How Historical Context Influenced Advertisements for Willa Cather's Fiction" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 87. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ADVERTISING “IN THESE TIMES:” HOW HISTORICAL CONTEXT INFLUENCED ADVERTISEMENTS FOR WILLA CATHER’S FICTION by Erika K. Hamilton A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Guy Reynolds Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2014 ADVERTISING “IN THESE TIMES:” HOW HISTORICAL CONTEXT INFLUENCED ADVERTISEMENTS FOR WILLA CATHER’S FICTION Erika K. Hamilton, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2014 Adviser: Guy Reynolds Willa Cather’s novels were published during a time of upheaval. In the three decades between Alexander’s Bridge and Sapphira and the Slave Girl, America’s optimism, social mores, culture, literature and advertising trends were shaken and changed by World War One, the “Roaring Twenties,” and the Great Depression.