Assessing the Precautionary Principle and the Proposed International Biosafety Protocol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fear Profiteers

THE FEAR PROFITEERS: Do ‘Socially Responsible’ Businesses Sow Health Scares to Reap Monetary Rewards? Edited by Bonner Cohen, Ph.D. John Carlisle Michael Fumento Michael Gough, Ph.D. Henry Miller, M.D. Steven Milloy Kenneth Smith Elizabeth Whelan, Sc.D., M.P.H. Hundreds of thousands of deaths a year from smoking is old hat, but possible death by toxic waste, now that’s exciting. The problem is, such presentations distort the ability of viewers to engage in accurate risk assessment. The average viewer who watches story after story on the latest alleged environmental terror can hardly be blamed for coming to the conclusion that cigarettes are a small problem compared with the hazards of parts per quadrillion of dioxin in the air, or for concluding that the drinking of alcohol, a known cause of birth weight and cancer, is a small problem compared with the possibility of eating quantities of Alar almost too small to measure. This in turn results in pressure on the bureaucrats and politicians to wage war against tiny or nonexistent threats. The “war” gets more coverage as these politicians and bureaucrats thunder that the planet could not possibly survive without their intervention, and the vicious cycle goes on. ––Michael Fumento, Science Under Siege CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... i-iii PREFACE.................................................................................................................I-III ACCIDENTALLY POISONOUS APPLES: Does Everything Cause -

Big Tobacco Helped Create “The Junkman”

Public Interest Reporting on the PR/Public Affairs Industry PR WATCH Volume 7, Number 3 Third Quarter 2000 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: The Usual Suspects New Book Explores “Politics of Health” Industry Hacks Turn Fear on its Head page 4 by Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber How Big Tobacco A number of leading figures in the anti-environmental “sound science” movement have teamed up to launch a new front group aimed Helped Create at smearing environmental and health activists as behind-the-scenes “the Junkman” conspirators who “sow health scares to reap monetary rewards.” page 5 In August, the “No More Scares” campaign announced its forma- tion at a Washington, DC press conference attacking Fenton Com- Tobacco’s Secondhand munications, one of the few public relations firms that represents Science of Smoke-Filled environmental advocacy groups. No More Scares spokesman Steven Milloy used the press conference to release a report titled “The Fear Rooms Profiteers,” which described Fenton as the “spider” at the center of a page 10 “tangled web of non-profit advocacy groups.” Inside PR, a public relations industry trade publication, termed the Readers Invited to press conference “an unprecedented attack” and noted that “Steven Trust Us, We’re Experts Milloy and his colleagues . could scarcely have timed their tirade page 12 against Fenton Communications and the public interest groups it rep- resents any worse. As Milloy and his cohorts accused consumer activists of provoking unnecessary alarm among the public, Ford and Bridge- stone/Firestone were providing consumers with a stark reminder of the appears on the website of Americans for Nonsmokers Flack Attack Rights at <http://www.no-smoke.org/internal.html>.) PR Watch has reported in the past on the antics of The Lancet story inspired our own visit to the Steven Milloy and his “Junk Science Home Page.” His tobacco archives as we were researching a new book tobacco connections, however, were first revealed on by Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber. -

Corona, False Alarm?: Facts and Figures

CORONA FALSE ALARM? Facts and Figures Karina Reiss & Sucharit Bhakdi Chelsea Green Publishing White River Junction, Vermont London, UK Copyright © 2020 by Goldegg Verlag GmbH, Berlin and Vienna. Originally published in Germany by Goldegg Verlag GmbH, Friedrichstraße 191 • D-10117 Berlin, in 2020 as Corona Fehlalarm? English translation copyright © 2020 by Goldegg Verlag GmbH, Berlin and Vienna. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Translated by Monika Wiedmann and Deirdre Anderson Author photos: Peter Pullkowski/Sucharit Bhakdi; Dagmar Blankenburg/Karina Reiss Cover design: Alexandra Schepelmann/Donaugrafik.at Layout and typesetting: Goldegg Verlag GmbH, Vienna This edition published by Chelsea Green Publishing, 2020. Printed in the United States of America. First printing September 2020. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Our Commitment to Green Publishing Chelsea Green sees publishing as a tool for cultural change and ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book manufacturing practices with our editorial mission and to reduce the impact of our business enterprise in the environment. We print our books and catalogs on chlorine-free recycled paper, using vegetable-based inks whenever possible. This book may cost slightly more because it was printed on paper that contains recycled fiber, and we hope you’ll agree that it’s worth it. Corona, False Alarm? was printed on paper supplied by Versa that is made of recycled materials and other controlled sources. ISBN 978-1-64502-057-8 (paperback) | ISBN 978-1-64502-058-5 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-64502-059-2 (audio book) Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945206 Chelsea Green Publishing 85 North Main Street, Suite 120 White River Junction, Vermont USA Somerset House London, UK www.chelseagreen.com For our sunshine on dark days. -

NABC Report 13.Www

PART VI LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Stanley Abramson Clifton Baile Arent Fox Kintner Plotkin & Kahn, University of Georgia PLLC 444 ADS Complex 1050 Connecticut Avenue, NW 425 River Rd. Washington DC 20036 Athens GA 30602 Jeffrey Adkisson Candace Bartholomew Grain and Feed Association of Illinois University of Connecticut 3521 Hollis Drive Cooperative Extension System Springfield IL 62707 1800 Asylum Ave. West Hartford CT 06117 Francis Adriaens Renessen LLC Giuseppe Battaglino 3000 Lakeside Dr. Suite 300S Ministry of Health Bannockburn IL 60015 Via Della Sierra Nevada 60 Rome 00144 Italy John Anderson Monsanto Roger Beachy 1609 Iredell Drive Donald Danforth Plant Science Center Raleigh NC 27608 7425 Forsyth Blvd. Box 1098 Wendy Anderson St. Louis MO 63105 Food Chemical News Margaret Becker Amy Ando NYS Department of Agriculture and 326 Mumford Hall Markets I Winners Circle University of Illinois Albany NY 12205 1301 W. Gregory Dr. Urbana IL 61801 P.S. Benepal Association of Research Directors Mary Arends-Kuenning Virginia State University University of Illinois Box 9061 408 Mumford Hall Petersburg VA 23806 1301 W. Gregory Dr. Urbana IL 61801 Gerona Berdak United Soybean Board Paul Backman 401 N. Michigan Ave. Penn State University Chicago IL 60611 College of Agricultural Sciences 217 Agricultural Administration Duane Berglund Building North Dakota State University University Park PA 16802 Box 5051 Fargo ND 58105 Participants Chris Bigall Fred Bradshaw Canadian Consulate General Route 1 180 N. Stetson Ave. Suite 2400 Box 259 Chicago IL 60601 Griggsville IL 62340 Wayne Bill William Brown Missouri Department of Agriculture University of Florida PO Box 630 PO Box 110200 1616 Missouri Blvd Gainsville FL 32611 Jefferson City MO 65102 William Browne Diane Birt Enterpriz Cook County Iowa State University 69 W. -

AIDS and the Public Debate

AIDS AND THE Public Debate AIDS AND THE Public Debate Historical and Contemporary Perspectives Caroline Hannaway Editor-in-chief Victoria A. Harden Editor John Parascandola Editor 1995 I OS Press Amsterdam • Oxford • Tokyo • Washington DC Ohmsha Tokyo • Osaka • Kyoto © Caroline Hannaway All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 90 5199 190 8 (IOS Press) ISBN 4 274 90013 4 C3047 (Ohmsha) Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 94-078473 Publisher IOS Press Van Diemenstraat 94 1013 CN Amsterdam Netherlands Distributor in the UK and Ireland IOS Press/Lavis Marketing 73 Lime Walk Headington Oxford OX3 7AD England Distributor in the USA and Canada IOS Press, Inc. P.O. Box 10558 Burke, VA 22009-0558 USA Distributor in Japan Ohmsha, Ltd. 3-1 Kanda Nishiki - Cho Chiyoda - Ku Tokyo 101 Japan LEGAL NOTICE The publisher is not responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS Contents Preface vii Introduction 1 Part I. AIDS and the United States Public Health Service The Early Days of AIDS as I Remember Them 9 C. Everett Koop The CDC and the Investigation of the Epidemiology of AIDS 19 James W. Curran The NIH and Biomedical Research on AIDS 30 Victoria A. Harden AIDS and the FDA 47 James Harvey Young AIDS: Reflections on the Past, Considerations for the Future 67 Anthony S. Fauci Part II. AIDS and American Society The National Commission on AIDS 77 June E. -

A Study of AIDS Michael B

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 63 | Number 1 Article 7 February 1996 A Study of AIDS Michael B. Flanagan Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Flanagan, Michael B. (1996) "A Study of AIDS," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 63: No. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol63/iss1/7 A Study of AIDS by Michael B. Flanagan, M.D. A World War II veteran of the Royal Navy, Dr. Flanagan graduated in Medicine at Trinity College, Dublin, in 1942. A past president of the San Francisco Catholic Physicians' Guild, Dr. Flanagan has defended Catholic pro life teaching on radio and television. This paper describes the epidemiology of the AIDS epidemic, and then gives the summary of the conclusions of the 1993 National Research Council's Report on "The Social Impact of AIDS in the United States." Three sources of information on the AIDS epidemic are then examined. 1. The medical literature on HIV infection in non-intravenous drug using prostitutes. 2. Studies on the transmission of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in disparate couples (where a partner is HIV+). 3. The 1993 Annual HIV / AIDS Surveillance Report from the Center for Disease Control (CDC). In the Conclusion these three sources are shown to confirm the Medical Research Council's Findings. Comparison of U.K. and U.S.A. AIDS Statistics AIDS statistics for the year 1991 offer an opportunity to compare the United States and United Kingdom figures, since they occurred in convenient multiples. At the end of 1991 the United Kingdom with over 50 million population had had February, 1996 61 about 4000 cases of AIDS. -

The Threat of an Avian Flu Pandemic Is Over-Hyped by Michael Fumento, JD

Virtual Mentor Ethics Journal of the American Medical Association April 2006, Volume 8, Number 4: 265-270. Op-Ed The Threat of an Avian Flu Pandemic is Over-Hyped by Michael Fumento, JD “It is only a matter of time before an avian flu virus—most likely H5N1—acquires the ability to be transmitted from human to human, sparking the outbreak of human pandemic influenza.” So declared Dr Lee Jong-wook, director-general of the World Health Organization last November [1]. Fortunately, the assertion is as mistaken as it is terrifying. Looking to the Data The best-kept secret of the current fuss and, sadly enough, hysteria over H5N1 is that the virus has been in existence well beyond its highly publicized Hong Kong appearance in 1997; the virus was initially discovered in Scottish chickens in 1959 [2]. The virus has therefore been mutating and making contact with humans for 47 years. If it hasn’t become pandemic in that half a century, it’s hardly inevitable that it will. Indeed, blood samples collected from rural Chinese in 1992 show 2-7 percent of those sampled were infected with some variant of H5; by extrapolation to the larger population, this equates to many millions of people [3]. Experts such as microbiologist Peter Palese of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York believe that more than a million of these infections could have been H5N1 infections, although samples were not tested for variants of neuraminidase, a surface antigen, the “N” in H5N1 [4]. The Chinese data demonstrate that if H5N1 were going to become pandemic in humans, “ it should have happened already,” Palese wrote in an e-mail on February 3, 2006. -

Supreme Court Appointment Process: President’S Selection of a Nominee

Supreme Court Appointment Process: President’s Selection of a Nominee Updated February 22, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44235 Supreme Court Appointment Process: President’s Selection of a Nominee Summary The appointment of a Supreme Court Justice is an event of major significance in American politics. Each appointment is of consequence because of the enormous judicial power the Supreme Court exercises as the highest appellate court in the federal judiciary. Appointments are usually infrequent, as a vacancy on the nine-member Court may occur only once or twice, or never at all, during a particular President’s years in office. Under the Constitution, Justices on the Supreme Court receive what can amount to lifetime appointments which, by constitutional design, helps ensure the Court’s independence from the President and Congress. The procedure for appointing a Justice is provided for by the Constitution in only a few words. The “Appointments Clause” (Article II, Section 2, clause 2) states that the President “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint ... Judges of the supreme Court.” The process of appointing Justices has undergone changes over two centuries, but its most basic feature—the sharing of power between the President and Senate—has remained unchanged: To receive appointment to the Court, a candidate must first be nominated by the President and then confirmed by the Senate. Political considerations typically play an important role in Supreme Court appointments. It is often assumed, for example, that Presidents will be inclined to select a nominee whose political or ideological views appear compatible with their own. -

A Timeline of the Wakefield Retraction

NEWS State of denial Scientists regularly debate hypotheses and interpretations, —Sandy Szwarc: A food editor and writer, sometimes feverishly. But in the public sphere, a Szwarc has rejected the idea that individuals different type of dissension is spreading through media with obesity face a heightened risk of to o outlets and online in an unprecedented way—one that premature death. Szwarc, a registered nurse, ph ck challenges basic concepts held as undeniable truths by calls government antiobesity efforts “a grossly Isto most researchers. ‘Science denialism’ is the rejection of exaggerated and fabricated scare campaign.” the scientific consensus, often in favor of a radical and On her blog “Junkfood Science,” Szwarc presents the ‘obesity controversial point of view. Here, we list what we see as a paradox,’ which refers to the alleged health benefits associated few of today’s most vocal denialists spreading ideas that with obesity, such as reports that obese individuals may have counter the consensus in health fields. higher survival rates of coronary artery disease than their normal- weight counterparts. Scientists reviewing this data, however, have suggested that this higher survival rate might be due to more —Mark and David Geier: This father-son duo, based aggressive treatment of people with obesity and other factors. in Washington, DC, was among the first to publish claims that the thimerosal preservative used in —Wolfgang Wodarg: Wodarg is a German physician and past certain vaccines causes autism (J. Am. Physicians head of health at the Council of Europe. Wodarg recently made Surg. 8, 6–11, 2003). Mark Geier holds a doctorate headlines accusing flu drug and vaccine makers of in genetics; his son, David, has a bachelor’s degree influencing the World Health Organization (WHO) to o in biology. -

N His Final Column of the Year, Foxnews.Com Science Columnist

TNR Online | Smoked Out (print) Page 1 of 4 PUNDIT FOR HIRE. Smoked Out by Paul D. Thacker Post date: 01.26.06 Issue date: 02.06.06 n his final column of the year, FoxNews.com science columnist Steven Milloy listed "THE TOP 10 JUNK SCIENCE CLAIMS OF 2005." For number nine, Milloy attacked the research of Michael Mann, a Penn State scientist who, in 1999, published research showing a dramatic rise in global temperatures during the twentieth century, after hundreds of years with little climate change. Calling Mann's science "dubious," Milloy praised Representative Joe Barton of Texas, whose calls for an investigation into Mann's methodology last June were cut short when the scientific community and members of Congress protested it as a witch hunt. Representative Sherwood Boehlert, the chairman of the House Committee on Science, wrote to Barton, "The only conceivable explanation for the investigation is to attempt to intimidate a prominent scientist and to have Congress put its thumbs on the scales of a scientific debate." Another conceivable explanation for the investigation is that Barton, as chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, is swimming in donations from oil companies. But that probably didn't bother Milloy, because he receives his own sponsorship from ExxonMobil. As revealed in Mother Jones last spring, between 2000 and 2003, ExxonMobil donated $90,000 to two nonprofits Milloy operates out of his house in Potomac, Maryland. Milloy's defense of Barton--and excoriation of Mann--is typical of his corporate-subsidized science reporting, in which he has attacked not only global warming, but also secondhand smoke studies and clean air regulations. -

Theatre of Science FORUM RICHARD WISEMAN Debating Creationists CHARLES L

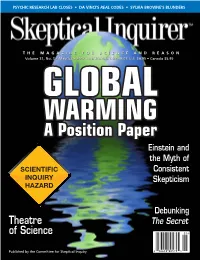

SI M-J 07 Cover V1 3/28/07 9:05 AM Page 1 PSYCHIC RESEARCH LAB CLOSES • DA VINCI’S REAL CODES • SYLVIA BROWNE’S BLUNDERS THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE AND REASON Volume 31, No. 3 • May/June 2007 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. $4.95 • Canada $5.95 Einstein and the Myth of SCIENTIFIC Consistent INQUIRY Skepticism HAZARD Debunking Theatre The Secret of Science 05> Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry 0556698 80575 SI M-J 2007 pgs 3/28/07 10:15 AM Page 2 THE COMMITTEE FOR SKEPTICAL INQUIRY FORMERLY THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL (CSICOP) AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY/TRANSNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, University at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto and Sciences, Professor of Philosophy and Robert L. Park, professor of physics, Univ. of Maryland Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Oregon Professor of Law, University of Miami John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist, Harvard England Journal of Medicine David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Columbia Univ. executive director CICAP, Italy consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas R. Hofstadter, professor of human under- Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. -

PR Watch 13 #1.2

Public Interest Reporting on the PR/Public Affairs Industry Volume 13, Number 1 First Quarter 2006 A PROJECT OF THE PR WATCH CENTER FOR MEDIA & DEMOCRACY WWW.PRWATCH.ORG ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: It Was a Very False Year: ‘True Spin’: An Oxymoron The 2005 Falsies Awards or a Lofty Goal? by Diane Farsetta page 6 As Father Time faded into history with the end of 2005, he was spin- ning out of control. George Lakoff and the Over the past twelve months, the ideal of accurate, accountable, civic- Motive for Metaphor minded news media faced nearly constant attack. Fake news abounded, page 8 from Pentagon-planted stories in Iraqi newspapers to corporate- and gov- ernment-funded video news releases aired by U.S. newsrooms. Enough CMD in the News payola pundits surfaced to constitute their own basketball team—Doug Bandow, Peter Ferrara, Maggie Gallagher, Michael McManus and Arm- page 13 strong Williams. (They could call themselves the “Syndicated Shills.”) Then there were the public relations campaigns that sought to rede- Anxious Al Caruba fine reality itself. The oil and nuclear industries could be greenwashed! page 14 Rights-abusing governments and labor-abusing companies could be white- washed! Junk food companies could be nutriwashed and genetically-mod- ified foods poorwashed! The only limitations were PR flacks’ imaginations—and their expense accounts. Viewed in sum, the extensive pollution of last year’s information envi- ronment could either make you cynical or have you convinced that two plus two really does equal five. Here at the Center for Media and Democracy, we realized that sort- ing through a year’s worth of outrageous spin to bestow this year’s Falsies Flack Attack popularized theories about the role of framing in the As the Center for Media and Democracy’s Diane public debate.