Defeating Kyoto: the Conservative Movement's Impact on U.S. Climate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathogenic Mutations Identified by a Multimodality Approach in 117 Japanese Fanconi Anemia Patients

ERRATA CORRIGE Bone Marrow Failure Pathogenic mutations identified by a multimodality approach in 117 Japanese Fanconi anemia patients Minako Mori, 1,2 Asuka Hira, 1 Kenichi Yoshida, 3 Hideki Muramatsu, 4 Yusuke Okuno, 4 Yuichi Shiraishi, 5 Michiko Anmae, 6 Jun Yasuda, 7Shu Tadaka, 7 Kengo Kinoshita, 7,8,9 Tomoo Osumi, 10 Yasushi Noguchi, 11 Souichi Adachi, 12 Ryoji Kobayashi, 13 Hiroshi Kawabata, 14 Kohsuke Imai, 15 Tomohiro Morio, 16 Kazuo Tamura, 6 Akifumi Takaori-Kondo, 2 Masayuki Yamamoto, 7,17 Satoru Miyano, 5 Seiji Kojima, 4 Etsuro Ito, 18 Seishi Ogawa, 3,19 Keitaro Matsuo, 20 Hiromasa Yabe, 21 Miharu Yabe 21 and Minoru Takata 1 1Laboratory of DNA Damage Signaling, Department of Late Effects Studies, Radiation Biology Center, Graduate School of Biostudies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; 2Department of Hematology and Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; 3Department of Pathology and Tumor Biology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan; 4Department of Pediatrics, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan; 5Laboratory of DNA Information Analysis, Human Genome Center, The Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo Japan; 6Medical Genetics Laboratory, Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kindai University, Osaka, Japan; 7Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan; 8Department of Applied Information Sciences, Graduate School of Information Sciences, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan; 9Institute of Development, Aging, -

KAKEHASHI Project (USA) Inbound Program for Young Japanese Americans Program Report

KAKEHASHI Project (USA) Inbound Program for Young Japanese Americans Program Report 1. Program Overview Under “Japan’s Friendship Ties Program”, 83 Young Japanese Americans who are interested in Japanese culture visited Japan. During the 8 days program from December 15 to December 22, 2015, the participants studied the Japanese government, society, history, culture, foreign policy, and much more. The participants aim to promote Japan through mediums such as SNS. 2. Participating Countries and Number of Participants U.S.A (83 Participants) 3. Prefectures Visited Tokyo, Shiga, Kyoto, Fukuoka 4. Program Schedule December 15 (Tue) Arrival at Narita International Airport December 16 (Wed) Orientation 【Lecture】“Japan’s Foreign Policy” by the North American Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 【Observation】Japanese Overseas Migration Museum December 17(Thu)~December 20(Sun) Local Program *Kyoto and Shiga 【History and Culture】Kinkaku-ji Temple, Kiyomizu-dera Temple, Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine 【School Exchange】The University of Shiga Prefecture 【Homestay】Meeting Hostfamilies, Farewell Party 【Workshop】 *Fukuoka 【Courtesy Call】Fukuoka City 【School Exchange】Fukuoka University 【History and Culture】The Ohori Park Noh Theater, Kushida Shrine 【Homestay】Meeting Hostfamilies, Farewell Party 【Workshop】 December 21(Mon)Move to Tokyo 【Reporting Session】 【Observation】IBM Japan Ltd. 1 December 22(Wed)Departure from Narita International Airport 5.USA / Young Japanese Americans Program Photos 12/16【Observation】Japanese Overseas 12/2【Observation】IBM Japan -

The Other Face of Fanaticism

February 2, 2003 The Other Face of Fanaticism By PANKAJ MISHRA New York Times Magazine On the evening of Jan. 30, 1948, five months after the independence and partition of India, Mohandas Gandhi was walking to a prayer meeting on the grounds of his temporary home in New Delhi when he was shot three times in the chest and abdomen. Gandhi was then 78 and a forlorn figure. He had been unable to prevent the bloody creation of Pakistan as a separate homeland for Indian Muslims. The violent uprooting of millions of Hindus and Muslims across the hastily drawn borders of India and Pakistan had tainted the freedom from colonial rule that he had so arduously worked toward. The fasts he had undertaken in order to stop Hindus and Muslims from killing one another had weakened him, and when the bullets from an automatic pistol hit his frail body at point-blank range, he collapsed and died instantly. His assassin made no attempt to escape and, as he himself would later admit, even shouted for the police. Millions of shocked Indians waited for more news that night. They feared unspeakable violence if Gandhi's murderer turned out to be a Muslim. There was much relief, also some puzzlement, when the assassin was revealed as Nathuram Godse, a Hindu Brahmin from western India, a region relatively untouched by the brutal passions of the partition. Godse had been an activist in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteers Association, or R.S.S.), which was founded in the central Indian city of Nagpur in 1925 and was devoted to the creation of a militant Hindu state. -

The Mass Graves of Al-Mahawil: the Truth Uncovered

IRAQ 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org Vol. 15, No. 5 (E) – May 2003 (212) 290-4700 The chaotic and unprofessional manner in which the mass graves around al- Hilla and al-Mahawil were unearthed made it impossible for many of the relatives of missing persons to identify positively many of the remains, or even to keep the human remains intact and separate. In the absence of international assistance, Iraqis used a backhoe to dig up the mass grave, literally slicing through countless bodies and mixing up remains in the process. At the end of the process, more than one thousand remains at the al-Mahawil grave sites were again reburied without being identified. In addition, because no forensic presence existed at the site, crucial evidence necessary for future trials of the persons responsible for the mass executions was never collected, and indeed may have Relatives of the missing search through bags containing corpses recovered from a been irreparably destroyed. mass grave near Hilla. © 2003 Peter Bouckaert/Human Rights Watch THE MASS GRAVES OF AL-MAHAWIL: THE TRUTH UNCOVERED 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] May 2003 Vol.15, No.5 (E) IRAQ THE MASS GRAVES OF AL-MAHAWIL: THE TRUTH UNCOVERED Table of Contents I. -

Kyoto City Council on Multicultural Policy Newsletter No.2

Kyoto City Council on Multicultural Policy Newsletter No.2 Edited and published by the International Relations Office. City of Kyoto The second council meeting of FY 2010 was held. <Time and Date> 10:00 A.M. to Noon, Tue. Sep. 7th, 2010 <Venue> International Community House <Agenda> Multicultural symbiosis from the view point of communication and parenting To live in Japan comfortably, it is important for foreign residents to communicate smoothly (with locals) and to lower the language barrier. The issues of language barrier and parenting by foreign residents were taken up and discussed in the meeting. As a result, useful information and clues that could be proposed to the city for the betterment of the society were gained. --Multicultural Childcare -- Utilizing actively the interaction between Japanese parents and foreign residents and those who have their roots in foreign countries in childcare arena. --Medical care for foreign residents-- (including those who have their roots in foreign countries) Language support related to receiving medical care with peace of mind for foreign residents and those who have their roots in foreign countries. --Supporting foreign women and their children— (including those having their roots in foreign countries) How should we help those who raise children and have difficulty in communicating? Report on the issue of nursery from multicultural symbiotic approach ~ Kibo-no-ie Catholic Hoikuen (nursery school) ~ Kibo-no-ie Catholic Hoikuen located in Minami Ward, Kyoto accepts many children having foreign nationalities or having their roots in foreign countries including Korean residents in Japan. They greet each other with in both Japanese and Korean. -

The Greenhouse Effect

The Greenhouse Effect I. SUMMARY AND OVERVIEWa This chapter examines what is variously called “climate change,” “global warming” and the “Greenhouse Effect.” These are all names for the same phenomenon: an increase in the Earth's temperature when heat is trapped near the surface. Most of this trapping is due to natural constituents of the air—water vapor, for example. But air pollutants also can trap heat, and as their concentrations increased so, too, can the Earth's temperature. Energy enters the Earth's atmosphere as sunlight. It strikes the surface, where it is converted into infrared radiation. Although the atmosphere is largely transparent to the visible radiation spectrum—sunlight—it is not to the infrared range. So heat that would other radiate into space is instead trapped in the atmosphere. That heat-trapping effect is good fortune for humanity and other life currently on Earth, because it raises the average temperature roughly 33 degrees Celsius above what it otherwise would be, making life as we know it possible.1 Over time, the energy entering the air has reached equilibrium with the energy leaving, creating Earth's current climate and, with it, the weather with which we are familiar on a day-to- day, week-to-week or year-to-year basis. With a Greenhouse Effect either greater or less than what has prevailed for millennia, the Earth would be quite different. In the absence of a Greenhouse Effect, the Earth would be ice covered. What it would be like with an enhanced Greenhouse Effect is the subject of this discussion. -

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

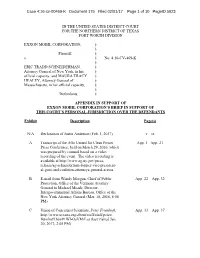

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

The Fear Profiteers

THE FEAR PROFITEERS: Do ‘Socially Responsible’ Businesses Sow Health Scares to Reap Monetary Rewards? Edited by Bonner Cohen, Ph.D. John Carlisle Michael Fumento Michael Gough, Ph.D. Henry Miller, M.D. Steven Milloy Kenneth Smith Elizabeth Whelan, Sc.D., M.P.H. Hundreds of thousands of deaths a year from smoking is old hat, but possible death by toxic waste, now that’s exciting. The problem is, such presentations distort the ability of viewers to engage in accurate risk assessment. The average viewer who watches story after story on the latest alleged environmental terror can hardly be blamed for coming to the conclusion that cigarettes are a small problem compared with the hazards of parts per quadrillion of dioxin in the air, or for concluding that the drinking of alcohol, a known cause of birth weight and cancer, is a small problem compared with the possibility of eating quantities of Alar almost too small to measure. This in turn results in pressure on the bureaucrats and politicians to wage war against tiny or nonexistent threats. The “war” gets more coverage as these politicians and bureaucrats thunder that the planet could not possibly survive without their intervention, and the vicious cycle goes on. ––Michael Fumento, Science Under Siege CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... i-iii PREFACE.................................................................................................................I-III ACCIDENTALLY POISONOUS APPLES: Does Everything Cause -

Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (University of North Carolina Press, 2016)

No Mercy Here 181 BOOK REVIEW Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (University of North Carolina Press, 2016) Viviane Saleh-Hanna* arah Haley’s NO MERCY HERE: GENDER, PUNIShmENT, AND THE MAKIng of Jim Crow Modernity is a beautifully written, empirical yet nuanced account of imprisoned and paroled Black women’s lives, deaths, and Sstruggles under convict leasing, chain gang, and parole regimes in Georgia at the turn of the twentieth century. Although the majority of Haley’s book focuses on Black women, she notes that 18 percent of Black female prison- ers were not yet 17 years old (42). One prisoner was 11 years old (96) at the time of her sentencing. The majority were young adults, many in their early twenties, some remaining imprisoned for decades. All, regardless of age, were sentenced to hard labor. Haley ties together wide-ranging archival data gathered from criminal justice agency reports and proceedings, government-sponsored commissions to examine prison and labor conditions, petitions and clemency applica- tions, letters, newspaper articles, era-specific research, Black women’s blues, historic speeches, and other social movement materials. This breadth of data coupled with Haley’s Black feminist analysis and methodology unearths the issues of Black women’s imprisonment, abuse, rape, and forced labor under Jim Crow’s carceral push into modernity. Haley also presents records of white women’s imprisonment, as well as their living and labor conditions, and discusses the responses these elicited from politicians, criminal justice agents, social organizations, and media outlets. Though the number of white women ensnared within Georgia’s * Viviane Saleh-Hanna is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Crime and Justice Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. -

Death Don't Have No Mercy: a Memoir of a Mother's

To view this document as two-page spreads, go to the View menu in Acrobat Reader and select “Page Layout” and “Facing” Death Don’t Have No Mercy A Memoir of a Mother’s Death BY MARIANA CAPLAN Well Death will go in any family in this land Well Death will go in every family in this land Well he’ll come to your house and he won’t stay long Well you’ll look in the bed and one of your family will be gone Death will go in any family in this land FROM “DEATH DON’T HAVE NO MERCY,” BY REV. GARY DAVIS NOT MANY OF US have seen another person receive a death sentence. Fewer still have been present to watch their own mother be given the final verdict. I had returned just days before from Asia. Ironically, the intention of the trip was to sit at the famous cremation grounds of Varanasi in India and in Pashpatinath in Nepal, where funeral pyres have burned for thousands of years. I was trying to face death as intimately as possible, to take the next step in a lifetime struggle to come to terms with my ultimate fate. A Jew by birth, I had been practicing for a decade under the guidance of Lee Lozowick in the Western Baul tradition, a rare synthesis that combines Vajrayana Buddhism with the devotional ecstasy of Vaisnava Hinduism, adapted to the needs of the contemporary Western practitioner. I engaged my experiment well, bearing witness to the death and decomposition of the body. -

God's Mercy and Justice in the Context of the Cosmic Conflict

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2019 God's Mercy and Justice in the Context of the Cosmic Conflict Romero Luiz Da Silva Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Da Silva, Romero Luiz, "God's Mercy and Justice in the Context of the Cosmic Conflict" (2019). Master's Theses. 135. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT GOD'S MERCY AND JUSTICE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE COSMIC CONFLICT by Romero Luiz Da Silva Adviser: Jo Ann Davidson ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: GOD'S MERCY AND JUSTICE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE COSMIC CONFLICT Name of researcher: Romero Luiz Da Silva Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jo Ann Davidson, PhD Date completed: July 2019 Problem When it comes to the right balance concerning God’s character of mercy and justice in relation to His dealings with sin in its different manifestations, a number of theologians, as well as Christians in general, have struggled to harmonize the existence of these two attributes in all God’s actions toward sinners. This difficulty has led many to think of divine mercy and justice as attributes that cannot fit together in what is called the cosmic conflict between good and evil. -

Big Tobacco Helped Create “The Junkman”

Public Interest Reporting on the PR/Public Affairs Industry PR WATCH Volume 7, Number 3 Third Quarter 2000 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: The Usual Suspects New Book Explores “Politics of Health” Industry Hacks Turn Fear on its Head page 4 by Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber How Big Tobacco A number of leading figures in the anti-environmental “sound science” movement have teamed up to launch a new front group aimed Helped Create at smearing environmental and health activists as behind-the-scenes “the Junkman” conspirators who “sow health scares to reap monetary rewards.” page 5 In August, the “No More Scares” campaign announced its forma- tion at a Washington, DC press conference attacking Fenton Com- Tobacco’s Secondhand munications, one of the few public relations firms that represents Science of Smoke-Filled environmental advocacy groups. No More Scares spokesman Steven Milloy used the press conference to release a report titled “The Fear Rooms Profiteers,” which described Fenton as the “spider” at the center of a page 10 “tangled web of non-profit advocacy groups.” Inside PR, a public relations industry trade publication, termed the Readers Invited to press conference “an unprecedented attack” and noted that “Steven Trust Us, We’re Experts Milloy and his colleagues . could scarcely have timed their tirade page 12 against Fenton Communications and the public interest groups it rep- resents any worse. As Milloy and his cohorts accused consumer activists of provoking unnecessary alarm among the public, Ford and Bridge- stone/Firestone were providing consumers with a stark reminder of the appears on the website of Americans for Nonsmokers Flack Attack Rights at <http://www.no-smoke.org/internal.html>.) PR Watch has reported in the past on the antics of The Lancet story inspired our own visit to the Steven Milloy and his “Junk Science Home Page.” His tobacco archives as we were researching a new book tobacco connections, however, were first revealed on by Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber.