'Not by Bread Only'? Common Right, Parish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography19802017v2.Pdf

A LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ON THE HISTORY OF WARWICKSHIRE, PUBLISHED 1980–2017 An amalgamation of annual bibliographies compiled by R.J. Chamberlaine-Brothers and published in Warwickshire History since 1980, with additions from readers. Please send details of any corrections or omissions to [email protected] The earlier material in this list was compiled from the holdings of the Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO). Warwickshire Library and Information Service (WLIS) have supplied us with information about additions to their Local Studies material from 2013. We are very grateful to WLIS for their help, especially Ms. L. Essex and her colleagues. Please visit the WLIS local studies web pages for more detailed information about the variety of sources held: www.warwickshire.gov.uk/localstudies A separate page at the end of this list gives the history of the Library collection, parts of which are over 100 years old. Copies of most of these published works are available at WCRO or through the WLIS. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust also holds a substantial local history library searchable at http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/. The unpublished typescripts listed below are available at WCRO. A ABBOTT, Dorothea: Librarian in the Land Army. Privately published by the author, 1984. 70pp. Illus. ABBOTT, John: Exploring Stratford-upon-Avon: Historical Strolls Around the Town. Sigma Leisure, 1997. ACKROYD, Michael J.M.: A Guide and History of the Church of Saint Editha, Amington. Privately published by the author, 2007. 91pp. Illus. ADAMS, A.F.: see RYLATT, M., and A.F. Adams: A Harvest of History. The Life and Work of J.B. -

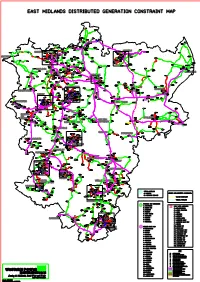

East Midlands Constraint Map-Default

EAST MIDLANDS DISTRIBUTED GENERATION CONSTRAINT MAP MISSON MISTERTON DANESHILL GENERATION NORTH WHEATLEY RETFOR ROAD SOLAR WEST GEN LOW FARM AD E BURTON MOAT HV FARM SOLAR DB TRUSTHORPE FARM TILN SOLAR GENERATION BAMBERS HALLCROFT FARM WIND RD GEN HVB HALFWAY RETFORD WORKSOP 1 HOLME CARR WEST WALKERS 33/11KV 33/11KV 29 ORDSALL RD WOOD SOLAR WESTHORPE FARM WEST END WORKSOPHVA FARM SOLAR KILTON RD CHECKERHOUSE GEN ECKINGTON LITTLE WOODBECK DB MORTON WRAGBY F16 F17 MANTON SOLAR FARM THE BRECK LINCOLN SOLAR FARM HATTON GAS CLOWNE CRAGGS SOUTH COMPRESSOR STAVELEY LANE CARLTON BUXTON EYAM CHESTERFIELD ALFORD WORKS WHITWELL NORTH SHEEPBRIDGE LEVERTON GREETWELL STAVELEY BATTERY SW STN 26ERIN STORAGE FISKERTON SOLAR ROAD BEVERCOTES ANDERSON FARM OXCROFT LANE 33KV CY SOLAR 23 LINCOLN SHEFFIELD ARKWRIGHT FARM 2 ROAD SOLAR CHAPEL ST ROBIN HOOD HX LINCOLN LEONARDS F20 WELBECK AX MAIN FISKERTON BUXTON SOLAR FARM RUSTON & LINCOLN LINCOLN BOLSOVER HORNSBY LOCAL MAIN NO4 QUEENS PARK 24 MOOR QUARY THORESBY TUXFORD 33/6.6KV LINCOLN BOLSOVER NO2 HORNCASTLE SOLAR WELBECK SOLAR FARM S/STN GOITSIDE ROBERT HYDE LODGE COLLERY BEEVOR SOLAR GEN STREET LINCOLN FARM MAIN NO1 SOLAR BUDBY DODDINGTON FLAGG CHESTERFIELD WALTON PARK WARSOP ROOKERY HINDLOW BAKEWELL COBB FARM LANE LINCOLN F15 SOLAR FARM EFW WINGERWORTH PAVING GRASSMOOR THORESBY ACREAGE WAY INGOLDMELLS SHIREBROOK LANE PC OLLERTON NORTH HYKEHAM BRANSTON SOUTH CS 16 SOLAR FARM SPILSBY MIDDLEMARSH WADDINGTON LITTLEWOOD SWINDERBY 33/11 KV BIWATER FARM PV CT CROFT END CLIPSTONE CARLTON ON SOLAR FARM TRENT WARTH -

192 Finedon Road Irthlingborough | Wellingborough

192 Finedon Road Irthlingborough | Wellingborough | Northamptonshire | NN9 5UB 192 FINEDON ROAD A beautifully presented detached family house with integral double garage set in half an acre located on the outskirts of Irthlingborough. The house is set well back from the road and is very private with high screen hedging all around, it is approached through double gates to a long gravelled driveway with beautifully maintained mature gardens to the side and rear, there is ample parking to the front leading to the garage. Internally the house has a flexible layout and is arranged over three floors with scope if required to create a separate guest annexe. On entering you immediately appreciate the feeling of light and space; there is a bright entrance hall with wide stairs to the upper and lower floors. On the right is a study and the large reception room which opens to the conservatory with access to a sun terrace, the conservatory leads through to a further conservatory currently used as a dining room. To the rear of the house is a family kitchen breakfast room which also opens to the conservatory/dining room. On the upper floor are the bedrooms, the master bedroom is a great size with a dressing area and an en-suite shower room. There are a further two double bedrooms and a smart family bathroom. On the lower floor is a good size utility room and a further double bedroom which opens to the large decked terrace and garden, there is also a further shower room and a separate guest cloakroom. -

Churchfield Stone Ltd. Establishing a Conservation Stone Quarry

Stonepits Quarry, Benefield Transport Statement Churchfield Stone Ltd. Establishing a Conservation Stone Quarry Stonepits Quarry, Benefield Transport Statement November 2012 1 Stonepits Quarry, Benefield Transport Statement QUALITY CONTROL Project Details Site Stonepits Quarry, Benefield Client Churchfield Stone Ltd. Project Establishing a Conservation Stone Quarry Name Position Date Prepared By Hilary Löfmark Consultant 11-10-12 Checked By Del Tester Director 12-10-12 Authorised By Del Tester Director 12-10-12 Status Revision Description Date Draft - 21-06-12 Issue 22-11-12 © DT Transport Planning No part of this document may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without the prior permission in writing of DT Transport Planning Limited. DT Transport Planning Limited disclaims any responsibility to the Client or any third party in respect to matters that are outside of the scope of this report. This report has been prepared with reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the contract with the Client and taking account of manpower, resources and testing devoted to it by agreement with the Client. This report is confidential to the Client and DT Transport Planning Limited accepts no responsibility of any nature to third parties to whom this report or any part thereof is made known. Any third party relies on the content of this report at their own risk. 2 Stonepits Quarry, Benefield Transport Statement CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Policy Considerations 3.0 Existing Conditions 4.0 Development Proposals 5.0 Transport Impact 6.0 Summary and Conclusions APPENDICES A Site Location Plan B Bus Route Plan and Timetable C Traffic Count Data and location photograph D Site Layout Plan E Proposed Site Access Junction F Northamptonshire County Council Comments, 1 August 2012 3 Stonepits Quarry, Benefield Transport Statement 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 DT Transport Planning Limited has been appointed by Churchfield Stone Ltd. -

B O R O U G H of K E T T E R I N G RURAL FORUM Meeting Held: 4Th

B O R O U G H OF K E T T E R I N G RURAL FORUM Meeting held: 4th April 2019 Present: Borough Councillors Councillor Jim Hakewill (Chair) Councillor Mark Rowley Parish Councillors Councillor Richard Barnwell (Cransley and Mawsley) Councillor Hilary Bull (Broughton) Councillor Fay Foster (Pytchley) Councillor Paul Gooding (Harrington) Councillor Patricia Hobson (Pytchley) Councillor Peter Hooton (Rushton) Councillor John Lillie (Brampton Ash) Councillor Frances Pope (Thorpe Malsor) Councillor Bernard Rengger (Sutton Bassett) Councillor Nick Richards (Wilbarston) Councillor Sue Wenbourne (Geddington, Newton and Little Oakley) Councillor James Woolsey (Warkton) County Councillors Councillor Allan Matthews Also Present: Brendan Coleman (Kettering Borough Council) Martin Hammond (Kettering Borough Council) Jo Haines (Kettering Borough Council) Sgt Robert Offord (Northamptonshire Police) Anne Ireson (Forum Administrator - KBC) Actions 18.RF.37 APOLOGIES Apologies were received from Councillors David Watson (Geddington, Newton and Little Oakley), Robin Shrive (Broughton), Alan Durn (Loddington), Brent Woodford (Ashley), Bruce Squires (Stoke Albany), Andy Macredie (Pytchley), Paul Waring (Warkton), Anne Lee (Kettering Town Forum Representative), Chris Smith-Haynes (NCC) and David Howes (KBC). 18.RF.38 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST None (Rural Forum No. 1) 4.4.19 18.RF.39 MINUTES RESOLVED that the minutes of the Rural Forum held on 31st January 2019 be approved as a correct record and signed by the Chair. 18.RF.40 MATTERS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES 18.RF.27 – Grit Bins A response had been received from Northamptonshire County Council, together with a briefing note, which had been emailed to all parishes, together with contact details for any queries. Updates would be brought back to the forum as necessary. -

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031 Regulation 19 consultation, February 2021 Contents Page Foreword 9 1.0 Introduction 11 2.0 Area Portrait 27 3.0 Vision and Outcomes 38 4.0 Spatial Development Strategy 46 EN1: Spatial development strategy EN2: Settlement boundary criteria – urban areas EN3: Settlement boundary criteria – freestanding villages EN4: Settlement boundary criteria – ribbon developments EN5: Development on the periphery of settlements and rural exceptions housing EN6: Replacement dwellings in the open countryside 5.0 Natural Capital – environment, Green Infrastructure, energy, 66 sport and recreation EN7: Green Infrastructure corridors EN8: The Greenway EN9: Designation of Local Green Space East Northamptonshire Council Page 1 of 225 East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2: Pre-Submission Draft (February 2021) EN10: Enhancement and provision of open space EN11: Enhancement and provision of sport and recreation facilities 6.0 Social Capital – design, culture, heritage, tourism, health 85 and wellbeing, community infrastructure EN12: Health and wellbeing EN13: Design of Buildings/ Extensions EN14: Designated Heritage Assets EN15: Non-Designated Heritage Assets EN16: Tourism, cultural developments and tourist accommodation EN17: Land south of Chelveston Road, Higham Ferrers 7.0 Economic Prosperity – employment, economy, town 105 centres/ retail EN18: Commercial space to support economic growth EN19: Protected Employment Areas EN20: Relocation and/ or expansion of existing businesses EN21: Town -

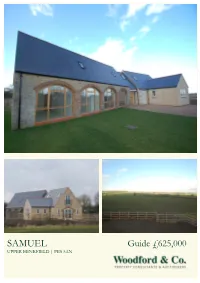

SAMUEL Guide £625,000 UPPER BENEFIELD | PE8 5AN

SAMUEL Guide £625,000 UPPER BENEFIELD | PE8 5AN Samuel, Middle Farm, Upper Benefield, Northamptonshire, PE8 5AN. A unique barn conversion offering versatile accommodation with 4 or 5 bedrooms, garden, parking and exceptional rural views. Hall | Living Room with Dining Area| Kitchen / Breakfast Room | Boot Room Guest Bedroom Suite | Bedroom 3 | Bedroom 5/ Snug | Family Bathroom ~ Master Bedroom Suite | Study Area | Games Room / Bedroom 4 | Laundry ~ Gardens | Parking | Views Location: Middle Farm is set in the heart of Upper Benefield. This attractive village evolved around the farms of the Biggin Estate, with many stone houses and cottages lining the street. The village has an active cricket club which serves as a 'pub'. The countryside around the village is accessible via a number of footpaths and bridleways. Oundle lies 5 miles away and offers a range of traditional family run shops, businesses and restaurants, as well a great choice of schooling. Corby is nearby and offers extensive facilities and a rail station with connections to London. Middle Farm: Middle Farm comprises a stunning Grade II Listed Georgian Farmhouse and a range of four traditional stone barns that are being converted to fine dwellings. Samuel is approached via the common drive, which passes the pond and willow tree before leading on to the gateway into the property. Samuel: This is an attractive and striking conversion and extension of the former stables belonging to Middle Farm and the home of Samuel, reputed to be the most handsome working Shire horse in the county. Tanchester Developments have designed and skilfully created a comfortable home that successfully combines modern and traditional materials, assembled by local craftsmen. -

The Poor in England Steven King Is Reader in History at Contribution to the Historiography of Poverty, Combining As It Oxford Brookes University

king&t jkt 6/2/03 2:57 PM Page 1 Alannah Tomkins is Lecturer in History at ‘Each chapter is fluently written and deeply immersed in the University of Keele. primary sources. The work as a whole makes an original The poor in England Steven King is Reader in History at contribution to the historiography of poverty, combining as it Oxford Brookes University. does a high degree of scholarship with intellectual innovation.’ The poor Professor Anne Borsay, University of Wales, Swansea This fascinating collection of studies investigates English poverty in England between 1700 and 1850 and the ways in which the poor made ends meet. The phrase ‘economy of makeshifts’ has often been used to summarise the patchy, disparate and sometimes failing 1700–1850 strategies of the poor for material survival. Incomes or benefits derived through the ‘economy’ ranged from wages supported by under-employment via petty crime through to charity; however, An economy of makeshifts until now, discussions of this array of makeshifts usually fall short of answering vital questions about how and when the poor secured access to them. This book represents the single most significant attempt in print to supply the English ‘economy of makeshifts’ with a solid, empirical basis and to advance the concept of makeshifts from a vague but convenient label to a more precise yet inclusive definition. 1700–1850 Individual chapters written by some of the leading, emerging historians of welfare examine how advantages gained from access to common land, mobilisation of kinship support, crime, and other marginal resources could prop up struggling households. -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 64

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS AST AND RESENT Page NP P Number 64 (2011) 64 Number Notes and News … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 3 Eton’s First ‘Poor Scholars’: William and Thomas Stokes of Warmington, Northamptonshire (c.1425-1495) … … … … … … … … … 5 Alan Rogers Sir Christopher Hatton … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 22 Malcolm Deacon One Thing Leads to Another: Some Explorations Occasioned by Extracts from the Diaries of Anna Margaretta de Hochepied-Larpent … … … … 34 Tony Horner Enclosure, Agricultural Change and the Remaking of the Local Landscape: the Case of Lilford (Northamptonshire) … … … … 45 Briony McDonagh The Impact of the Grand Junction Canal on Four Northamptonshire Villages 1793-1850 … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 53 Margaret Hawkins On the Verge of Civil War: The Swing Riots 1830-1832 … … … … … … … 68 Sylvia Thompson The Roman Catholic Congregation in Mid-nineteenth-century Northampton … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 81 Margaret Osborne Labourers and Allotments in Nineteenth-century Northamptonshire (Part 1) … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 89 R. L. Greenall Obituary Notices … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 98 Index … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 103 Cover illustration: Portrait of Sir Christopher Hatton as Lord Chancellor and Knight of the Garter, a copy of a somewhat mysterious original. Described as ‘in the manner of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger’ it was presumably painted between Hatton’s accession to the Garter in 1588 and his death in 1591. The location and ownership of the original are unknown, and it was previously unrecorded by the National Portrait Gallery. It Number 64 2011 £3.50 may possibly be connected with a portrait of Hatton, formerly in the possession of Northamptonshire Record Society the Drake family at Shardeloes, Amersham, sold at Christie’s on 26 July 1957 (Lot 123) and again at Sotheby’s on 4 July 2002. -

GEDDINGTON, NEWTON and LITTLE OAKLEY PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES of the MEETING HELD on 10Th AUGUST 2020

GEDDINGTON, NEWTON AND LITTLE OAKLEY PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 10th AUGUST 2020. This was held as a virtual meeting – made necessary as a result of the coronavirus. MEMBERS PRESENT: Councillors N Batchelor (Chair), T Bailey, S Wenbourne, P Goode, D Watson, M Rowley, J Padwick, C Buckseall. APOLOGIES: A Foulke. 136/21: DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest. 137/21: MINUTE’S SILENCE IN MEMORY OF CLLR ANGUS GORDON. A tribute was given to Angus Gordon, a former parish councillor of over twenty years. Cllr Batchelor said that he had done great things in the community, a very kind person and known by so many people. A minute’s silence followed the tribute, with the funeral details then being given. 138/21: CO-OPTION Paul Johnson has expressed an interest in being co-opted on to the Parish Council. The relevant criteria have been met. Cllr Rowley therefore formally nominated Mr Johnson. Cllr Goode seconded the nomination. Councillors were unanimously in favour of the nomination. Paul Johnson was therefore welcomed as a councillor. At this point Cllr Batchelor informed the meeting that Cllr Wenbourne would be leaving the village shortly and would therefore resign as a councillor. Cllr Rowley informed Cllr Wenbourne that the three mile rule applies to when you apply to become a councillor, but as she already is a councillor, the post does not have to be vacated until the next election, which is in May 2021. Cllr Wenbourne expressed a wish to stay until this date. 139/21: PUBLIC SESSION. -

Iiill Peasant Revolt in France and England

Peasant Revolt in France and England: a Comparison By C. S. L. DAVIES R.OFESSOR. Mousnier's Fureurs Pay- had, after all, little contact with each other, so p sannes, published in I967, is now avail- that merely chronological coincidence is not able in English with a rather less lively in itself significant. Fortunately an excellent title? It is an attempt to broaden the contro- review from the standpoint of the three coun- versy on the nature of French peasant revolts tries concerned is available by a troika of that has raged since the publication of Boris American historians. 8 My purpose is rather to Porclmev's book in I948, by comparing attempt to see how far Professor Mousnier's revolts fix seventeenth-century France, rZussia, typology of peasant revolt is applicable to and China. 2 For Frmlce, these consist of the England. He has specifically refrained from .Croquants of Saintonge, Augoumois, and making this particular comparison because Poitou in x636 and of P~rigord in I637, the another book of the same series is to deal with Nu-Pieds of Normandy in I639, and the Ton'& England. But since that work is concerned hens of Brittany in I675. For Russia, he with the Puritan R.evolution which, con- examines peasant involvement in the dynastic sidered as a "peasant revolt" was in a sense struggles kalown as the "Time of Troubles" at the revolt that never was, I feel justified in the begimfing of the seventeenth century, most attempting the comparison although inevit- notably that led by the ex-slave Bolomikov; ably it is not possible to do more thml treat a and the revolt of Stenka Razin, a Cossack who few general themes. -

Kinsmore £385,000 Upper Benefield | Pe8 5As

KINSMORE £385,000 UPPER BENEFIELD | PE8 5AS Kinsmore, Weldon Road, Upper Benefield, Northamptonshire, PE8 5AS. A detached bungalow, with scope for further development, with gardens and paddock, in all about 1.5 acres, enjoying far reaching rural views. Hall | Kitchen | Dining Room | Sitting Room | Boot Room | Cloakroom Conservatory ~ Two Bedrooms | Bathroom | Attic Space ~ Paddock | Gardens | Garage Location: Upper Benefield is a popular village approximately 5 miles to the West of Oundle. There are a number of footpaths and bridleways leading from the village over the gently rolling neighbouring countryside. Oundle offers a range of traditional, family run shops, businesses and restaurants set around the historic market place. There are excellent schools too. More extensive facilities as well as main line rail travel are available in Kettering, Corby and Peterborough. The Property: Kinsmore is a modern bungalow that has been much improved in recent years, including the installation of central heating and double glazing. There is scope for further development, which would be worthwhile to maximise the potential and the enjoyment that the property offers, as it is set in such a wonderful, rural location with marvellous views to the south and west. The overall holding extends to approx imately 1.5 acres, probably suiting those with an equestrian or canine interest. As with most rural properties, Kinsmore is entered via the large boot room which also serves as a utility room. A door leads to the inner hall which in turn leads to the conservatory, WC and to the kitchen. The kitchen, which has fitted units and enjoys a dual aspect with a view over the paddock and countryside beyond.