Regular Expressions 11 I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIX and Computer Science Spreading UNIX Around the World: by Ronda Hauben an Interview with John Lions

Winter/Spring 1994 Celebrating 25 Years of UNIX Volume 6 No 1 "I believe all significant software movements start at the grassroots level. UNIX, after all, was not developed by the President of AT&T." Kouichi Kishida, UNIX Review, Feb., 1987 UNIX and Computer Science Spreading UNIX Around the World: by Ronda Hauben An Interview with John Lions [Editor's Note: This year, 1994, is the 25th anniversary of the [Editor's Note: Looking through some magazines in a local invention of UNIX in 1969 at Bell Labs. The following is university library, I came upon back issues of UNIX Review from a "Work In Progress" introduced at the USENIX from the mid 1980's. In these issues were articles by or inter- Summer 1993 Conference in Cincinnati, Ohio. This article is views with several of the pioneers who developed UNIX. As intended as a contribution to a discussion about the sig- part of my research for a paper about the history and devel- nificance of the UNIX breakthrough and the lessons to be opment of the early days of UNIX, I felt it would be helpful learned from it for making the next step forward.] to be able to ask some of these pioneers additional questions The Multics collaboration (1964-1968) had been created to based on the events and developments described in the UNIX "show that general-purpose, multiuser, timesharing systems Review Interviews. were viable." Based on the results of research gained at MIT Following is an interview conducted via E-mail with John using the MIT Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS), Lions, who wrote A Commentary on the UNIX Operating AT&T and GE agreed to work with MIT to build a "new System describing Version 6 UNIX to accompany the "UNIX hardware, a new operating system, a new file system, and a Operating System Source Code Level 6" for the students in new user interface." Though the project proceeded slowly his operating systems class at the University of New South and it took years to develop Multics, Doug Comer, a Profes- Wales in Australia. -

Ifdef Considered Harmful, Or Portability Experience with C News Henry Spencer – Zoology Computer Systems, University of Toronto Geoff Collyer – Software Tool & Die

#ifdef Considered Harmful, or Portability Experience With C News Henry Spencer – Zoology Computer Systems, University of Toronto Geoff Collyer – Software Tool & Die ABSTRACT We believe that a C programmer’s impulse to use #ifdef in an attempt at portability is usually a mistake. Portability is generally the result of advance planning rather than trench warfare involving #ifdef. In the course of developing C News on different systems, we evolved various tactics for dealing with differences among systems without producing a welter of #ifdefs at points of difference. We discuss the alternatives to, and occasional proper use of, #ifdef. Introduction portability problems are repeatedly worked around rather than solved. The result is a tangled and often With UNIX running on many different comput- impenetrable web. Here’s a noteworthy example ers, vaguely UNIX-like systems running on still more, from a popular newsreader.1 See Figure 1. Observe and C running on practically everything, many peo- that, not content with merely nesting #ifdefs, the ple are suddenly finding it necessary to port C author has #ifdef and ordinary if statements (plus the software from one machine to another. When differ- mysterious IF macros) interweaving. This makes ences among systems cause trouble, the usual first the structure almost impossible to follow without impulse is to write two different versions of the going over it repeatedly, one case at a time. code—one per system—and use #ifdef to choose the appropriate one. This is usually a mistake. Furthermore, given worst case elaboration and nesting (each #ifdef always has a matching #else), Simple use of #ifdef works acceptably well the number of alternative code paths doubles with when differences are localized and only two versions each extra level of #ifdef. -

Usenet News HOWTO

Usenet News HOWTO Shuvam Misra (usenet at starcomsoftware dot com) Revision History Revision 2.1 2002−08−20 Revised by: sm New sections on Security and Software History, lots of other small additions and cleanup Revision 2.0 2002−07−30 Revised by: sm Rewritten by new authors at Starcom Software Revision 1.4 1995−11−29 Revised by: vs Original document; authored by Vince Skahan. Usenet News HOWTO Table of Contents 1. What is the Usenet?........................................................................................................................................1 1.1. Discussion groups.............................................................................................................................1 1.2. How it works, loosely speaking........................................................................................................1 1.3. About sizes, volumes, and so on.......................................................................................................2 2. Principles of Operation...................................................................................................................................4 2.1. Newsgroups and articles...................................................................................................................4 2.2. Of readers and servers.......................................................................................................................6 2.3. Newsfeeds.........................................................................................................................................6 -

The Following Paper Was Originally Published in the Proceedings of the Eleventh Systems Administration Conference (LISA ’97) San Diego, California, October 1997

The following paper was originally published in the Proceedings of the Eleventh Systems Administration Conference (LISA ’97) San Diego, California, October 1997 For more information about USENIX Association contact: 1. Phone: 510 528-8649 2. FAX: 510 548-5738 3. Email: [email protected] 4. WWW URL:http://www.usenix.org Shuse At Two: Multi-Host Account Administration Henry Spencer – SP Systems ABSTRACT The Shuse multi-host account administration system [1] is now two years old, and clearly a success. It is managing a user population of 20,000+ at Sheridan College, and a smaller but more demanding population at a local ‘‘wholesaler ’’ ISP, Cancom. This paper reviews some of the experiences along the way, and attempts to draw some lessons from them. Shuse: Outline and Status After some trying moments early on, Shuse is very clearly a success. In mid-autumn 1996, Sheridan Shuse [1] is a multi-host account administration College’s queue of outstanding help-desk requests was system designed for large user communities (tens of two orders of magnitude shorter than it had been in thousands) on possibly-heterogeneous networks. It previous years, despite reductions in support man- adds, deletes, moves, renames, and otherwise adminis- power. Favorable comments were heard from faculty ters user accounts on multiple servers, with functional- who had never previously had anything good to say ity generally similar to that of Project Athena’s Ser- about computing support. However, there was natu- vice Management System [2]. rally still a wishlist of desirable improvements. Shuse uses a fairly centralized architecture. All At around the same time, ex-Sheridan people user/sysadmin requests go to a central daemon were involved in getting Canadian Satellite Communi- (shused) on a central server host, via gatekeeper pro- cations Inc. -

Advanced Tcl E D

PART II I I . A d v a n c Advanced Tcl e d T c l Part II describes advanced programming techniques that support sophisticated applications. The Tcl interfaces remain simple, so you can quickly construct pow- erful applications. Chapter 10 describes eval, which lets you create Tcl programs on the fly. There are tricks with using eval correctly, and a few rules of thumb to make your life easier. Chapter 11 describes regular expressions. This is the most powerful string processing facility in Tcl. This chapter includes a cookbook of useful regular expressions. Chapter 12 describes the library and package facility used to organize your code into reusable modules. Chapter 13 describes introspection and debugging. Introspection provides information about the state of the Tcl interpreter. Chapter 14 describes namespaces that partition the global scope for vari- ables and procedures. Namespaces help you structure large Tcl applications. Chapter 15 describes the features that support Internationalization, includ- ing Unicode, other character set encodings, and message catalogs. Chapter 16 describes event-driven I/O programming. This lets you run pro- cess pipelines in the background. It is also very useful with network socket pro- gramming, which is the topic of Chapter 17. Chapter 18 describes TclHttpd, a Web server built entirely in Tcl. You can build applications on top of TclHttpd, or integrate the server into existing appli- cations to give them a web interface. TclHttpd also supports regular Web sites. Chapter 19 describes Safe-Tcl and using multiple Tcl interpreters. You can create multiple Tcl interpreters for your application. If an interpreter is safe, then you can grant it restricted functionality. -

A Short UNIX History How Our Culture Created Linux

A Short UNIX History or How Our Culture Created Linux Clement T. Cole Witch Doctor Compaq [email protected] A UNIX Family History RIG CMU CMU CMU CMU OSF1 Tru64 Linux Accent Mach Mach Mach Linux . 1.X Other Players 2.5 3.0 99 Minix Multics Idris BBN GNU C 386/BSD FreeBSD Generic TCP/IP Net 2.0 Net 1.0 4BSD 4.1A UCB BSD 2BSD 3BSD 4.1BSD 4.2BSD 4.3BSD 4.3Tahoe 4.3Reno 4.4BSD Research X Windows X 10 X 11 32V 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed NT/OS2 NT/Win PWB PWB/UNIX PWB 1.0 PWB 2.0 Sys III Sys V Sys V. SVR3 SVR4 SVR4/ 2 ESMP µSoft/SCO µSoft/Xenix SCO/Xenix SCO/UNIX UNIXWARE ‘72 ‘73 ‘74 ‘75 ‘76 ‘77 ‘78 ‘79 ‘80 ‘81 ‘82 ‘83 ‘84 ‘85 ‘86 ‘87 ‘88 ‘89 ‘90 ‘91 ‘92 ‘93 Clem Cole Themes ◆ Something new is really something old. ◆ The Open Source Culture predates UNIX and Linux. ◆ Evolution is good. ◆ Fighting is not always bad, but learn when it’s good enough and stop fighting. Clem Cole Agenda ◆ Technical History ◆ Legal History ◆ What it all means Clem Cole A Word on Engineers “Good programmers write good programs. Great programmers start and build upon other great programmer’s work.” Unknown origin, often attributed to Fred Brooks. Clem Cole Multics ◆ MULTiplexed Information and Computing Service ❖ or “Many Unbelievably Large Tables In Core Simultaneously.” ❖ Actually very cool system, see: The Multics system; an Examination of its Structure, Elliott I. -

27.1 Perl Perl Perl

27 Perl Perl Perl www.perl.org www.perl.com Larry www.wall.org/~larry Perl Perl Perl 27.1 Perl Perl Perl 1986 Larry multilevel-secure wide-area network VAXen Sun 1200-baud Larry rn patch warp Larry feeping creaturism rn patch feeping creaturism feature creep 643 644 Larry rn Larry VAXen Sun Larry B-news Larry news append synchronize RCS Revision Control System news rn Larry Larry awk awk Larry Perl Larry Dan Faigin Larry Mark Biggar Larry Gloria Larry Pearl Perl Larry PEARL Larry Perl Practical Extraction And Report Language Perl pattern matching filehandle scalar format associative array regular expression rn manpage 15 Perl sed awk Perl Usenet 645 Larry Larry Larry Perl Perl Larry Henry Spencer Larry Larry Perl Perl Perl 1.0 1987 12 18 Perl Perl 2.0 1988 6 Randal Schwartz Just Another Perl Hacker 1989 Tom Christiansen Baltimore Usenix Perl Perl 3.0 1989 10 Perl GNU 1990 3 Larry Perl Larry Randal Pink Camel 1991 Perl 4.0 Artistic License GPL Perl 5 1994 10 Perl object module Perl 5 Economist 1995 CPAN Perl 1996 Jon Orwant Perl Journal Blue Camel 1997 O'Reilly Perl (TPC) San Jose, California CPAST Comprehensive Perl Arcana Society Tapestry http://history.perl.org 27.2 Perl 1990 Usenet Larry Black Perl Perl 3 Perl 5 Larry JPL Jet Propulsion Lab Perl Larry O'Reilly & Associates Perl rn Larry Perl rn Larry Perl rn 646 Larry Perl Sharon Hopkins Sharon Perl Usenix Winter 1992 Perl Camels and Needles: Computer Poetry Meets the Perl Programming Language Perl Perl Sharon Economist Guardian #!/usr/bin/perl APPEAL: listen (please, please); open yourself, wide; join (you, me), connect (us,together), tell me. -

LICENSES: Azul Zing Licenses and Copyrights the Azul Systems(R

LICENSES: Azul Zing Licenses and Copyrights The Azul Systems(r) Zing(tm) platform runs Java(tm) applications. The Zing product has two components, the Zing Virtual Machine (ZVM) that is a Java Virtual Machine (JVM), and the Zing System Tools (ZST) that manage the elastic and highly scalable, shared memory resources. Azul incorporates some third-party licensed software packages into its products. Some of these may or may not have distribution restrictions and some may have only reporting requirements. This document lists the third-party licensed software packages for all Zing products. Licenses and Copyright Notices GNU General Public Licenses * http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-2.0.txt General Lesser Public Licenses * http://www.gnu.org/licenses/lgpl-2.1.txt Apache Licenses * http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-1.1 * http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0 Eclipse Public License * http://www.eclipse.org/licenses/edl-v10.html Auxiliary Copyright Notices In addition to the above licenses, there are numerous copyright notices by individual contributors where the author contributes the code under one of the above licenses, with the requirement that the copyright notices be published. These third-party software licenses are published below. Legal Notices Published August 14, 2020 Copyright (c) 2005-2020, Azul Systems, Inc. 385 Moffett Park Drive, Suite 115, Sunnyvale, CA 94089- 1208. All rights reserved. Azul Systems, the Azul Systems logo, Zulu and Zing are registered trademarks, and ReadyNow! is a trademark of Azul Systems Inc. Java and OpenJDK are trademarks of Oracle Corporation and/or its affiliated companies in the United States and other countries. -

POSIX Programmer's Guide Writing Portable UNIX Programs with the POSIX.1 Standard

Page iii POSIX Programmer's Guide Writing Portable UNIX Programs with the POSIX.1 Standard Donald A. Lewine Data General Corporation O'Reilly & Associates, Inc 103 Morris Street, Suite A Sebastopol, CA 95472 Page iv POSIX Programmer's Guide by Donald A. Lewine Editor: Dale Dougherty Copyright © 1991 O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Printing History April 1991: First edition December 1991: Minor corrections. Appendix G added. July 1992: Minor corrections. November 1992: Minor corrections. March 1994: Minor corrections and updates. NOTICE Portions of this text have been reprinted from IEEE Std 1003.1-1988, IEEE Standard Portable Operating System for Computer Environments, copyright © 1988 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., and IEEE Std 1003.1-1990, Information Technology—Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX)—Part 1: System Application Program Interface (API) [C Language], copyright © 1990 by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc., with the permission of the IEEE Standards Department. Nutshell Handbook and the Nutshell Handbook logo are registered trademarks of O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O'Reilly and Associates, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. Please address comments and questions in care of the publisher: O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. -

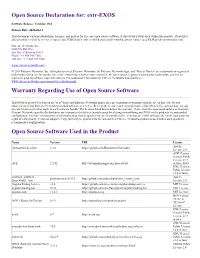

Extr-EXOS Warranty Regarding Use of Open Source Software Open

Open Source Declaration for: extr-EXOS Software Release: Versions: 30.6 Release Date: 2020-03-13 This document contains attributions, licenses, and notices for free and open source software (Collectively FOSS) used within this product. If you have any questions or wish to receive a copy of any FOSS source code to which you may be entitled, please contact us at [email protected]. Extreme Networks, Inc 6480 Via Del Oro San Jose, California 95119 Phone / +1 408.904.7002 Toll-free / + 1 888.257.3000 www.extremenetworks.com © 2019 Extreme Networks, Inc. All rights reserved. Extreme Networks, the Extreme Networks logo, and "Project Names" are trademarks or registered trademarks of Extreme Networks, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. All other names, registered trademarks, trademarks, and service marks are property of their respective owners. For additional information on Extreme Networks trademarks, see www.extremenetworks.com/company/legal/trademarks Warranty Regarding Use of Open Source Software This FOSS is provided to you on an "as is" basis, and Extreme Networks makes no representations or warranties for the use of this code by you independent of any Extreme Networks provided software or services. Refer to the licenses and copyright notices listed below for each package for any specific license terms that apply to each software bundle. The licenses listed below define the warranty, if any, from the associated authors or licensors. Extreme Networks specifically disclaims any warranties for defects caused caused by altering or modifying any FOSS or the products' recommended configuration. You have no warranty or indemnification claims against Extreme Networks in the event that the FOSS infringes the intellectual property rights of a third party. -

Perl Cookbook

;-_=_Scrolldown to the Underground_=_-; Perl Cookbook http://kickme.to/tiger/ By Tom Christiansen & Nathan Torkington; ISBN 1-56592-243-3, 794 pages. First Edition, August 1998. (See the catalog page for this book.) Search the text of Perl Cookbook. Index Symbols | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z Table of Contents Foreword Preface Chapter 1: Strings Chapter 2: Numbers Chapter 3: Dates and Times Chapter 4: Arrays Chapter 5: Hashes Chapter 6: Pattern Matching Chapter 7: File Access Chapter 8: File Contents Chapter 9: Directories Chapter 10: Subroutines Chapter 11: References and Records Chapter 12: Packages, Libraries, and Modules Chapter 13: Classes, Objects, and Ties Chapter 14: Database Access Chapter 15: User Interfaces Chapter 16: Process Management and Communication Chapter 17: Sockets Chapter 18: Internet Services Chapter 19: CGI Programming Chapter 20: Web Automation The Perl CD Bookshelf Navigation Copyright © 1999 O'Reilly & Associates. All Rights Reserved. Foreword Next: Preface Foreword They say that it's easy to get trapped by a metaphor. But some metaphors are so magnificent that you don't mind getting trapped in them. Perhaps the cooking metaphor is one such, at least in this case. The only problem I have with it is a personal one - I feel a bit like Betty Crocker's mother. The work in question is so monumental that anything I could say here would be either redundant or irrelevant. However, that never stopped me before. Cooking is perhaps the humblest of the arts; but to me humility is a strength, not a weakness. -

Cisco Telepresence MCU 4.4 MR1 Open Source Documentation

Open Source Used In Cisco TelePresence MCU 4.4(MR1) This document contains the licenses and notices for open source software used in this product. With respect to the free/open source software listed in this document, if you have any questions or wish to receive a copy of the source code to which you are entitled under the applicable free/open source license(s) (such as the GNU Lesser/General Public License), please contact us at [email protected]. In your requests please include the following reference number 78EE117C99-39081909 Contents 1.1 binutils 2.14 1.1.1 Available under license 1.2 Brian Gladman's AES Implementation 11-01-11 1.2.1 Available under license 1.3 dhcp 4.1.1 1.3.1 Available under license 1.4 FatFS R0.05 1.4.1 Available under license 1.5 FreeBSD kernel 8.2 :FreeBSD 8.2 1.5.1 Available under license 1.6 G.722 2.0 1.6.1 Available under license 1.7 HMAC n/a Open Source Used In Cisco TelePresence MCU 4.4(MR1) 1 1.7.1 Available under license 1.8 libjpeg 6b 1.8.1 Notifications 1.8.2 Available under license 1.9 linux 2.6.36.2 1.9.1 Available under license 1.10 lua 5.0 1.10.1 Available under license 1.11 lwIP 1.4.0 :rc1 1.11.1 Available under license 1.12 net-snmp 5.4.1 1.12.1 Available under license 1.13 NetBSD kernel 1.6 1.13.1 Available under license 1.14 Newlib 1.17.0 1.14.1 Available under license 1.15 OpenSSL 1.0.0j 1.15.1 Notifications 1.15.2 Available under license 1.16 picoOS 1.0.0 1.16.1 Available under license 1.17 PortAudio v12 1.17.1 Available under license 1.18 Pthreads-win32 snap-2000-08-10 1.18.1 Available under license 1.19 sha1 01/08/2005 1.19.1 Available under license 1.20 unbound 1.4.10 1.20.1 Available under license 1.21 usbd 0.1.2 1.21.1 Available under license 1.22 Zip Utils September 2005 1.22.1 Available under license 1.1 binutils 2.14 1.1.1 Available under license : GNU GENERAL PUBLIC LICENSE Version 2, June 1991 Open Source Used In Cisco TelePresence MCU 4.4(MR1) 2 Copyright (C) 1989, 1991 Free Software Foundation, Inc.