The Research Scientist's Psalm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomos and Narrative Before Nomos and Narrative

Nomos and Narrative Before Nomos and Narrative Steven D. Fraade* I imagine that when Robert Cover's Nomos and Narrative essay' first reached the editors of the Harvard Law Review, their befuddlement derived not so much from Cover's framing of his review of the 1982 Supreme Court term with a philosophically opaque discussion of the interdependence of law and narrative, but from the illustrations that he drew from biblical and rabbinic texts of ancient and medieval times. For Cover, both intellectually and as a matter of personal commitment, these ancient texts evoke a "nomian world," rooted more in communally shared stories of legal origins and utopian ends than in the brutalities of institutional enforcement, one from which modem legal theory and practice have much to learn and to emulate. Since my own head is buried most often in such ancient texts, rather than in modem courts, I thought it appropriate to reflect, by way of offering more such texts for our consideration, on the long-standing preoccupation with the intersection and interdependency of the discursive modes of law and narrative in Hebrew biblical and rabbinic literature, without, I hope, romanticizing them. Indeed, I wish to demonstrate that what we might think of as a particularly modem tendency to separate law from narrative, has itself an ancient history, and to show how that tendency, while recurrent, was as recurrently resisted from within Jewish tradition. In particular, at those cultural turning points in which laws are extracted or codified from previous narrative settings, I hope to show that they are also renarrativized (or remythologized) so as to address, both ideologically and rhetorically, changed socio-historical settings.2 I will do so through admittedly * Steven D. -

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

The Importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls for the Study of the Explicit Quotations in Ad Hebraeos

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research The importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls for the study of the explicit quotations inAd Hebraeos Author: The important contribution that the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) hold for New Testament studies is Gert J. Steyn¹ probably most evident in Ad Hebraeos. This contribution seeks to present an overview of Affiliation: relevant extant DSS fragments available for an investigation of the Old Testament explicit 1Department of New quotations and motifs in the book of Hebrews. A large number of the explicit quotations in Testament Studies, Faculty of Hebrews were already alluded to, or even quoted, in some of the DSS. The DSS are of great Theology, University of importance for the study of the explicit quotations in Ad Hebraeos in at least four areas, namely Pretoria, South Africa in terms of its text-critical value, the hermeneutical methods employed in both the DSS and Project leader: G.J. Steyn Hebrews, theological themes and motifs that surface in both works, and the socio-religious Project number: 02378450 background in which these quotations are embedded. After these four areas are briefly explored, this contribution concludes, among others, that one can cautiously imagine a similar Description Jewish sectarian matrix from which certain Christian converts might have come – such as the This research is part of the project, ‘Acts’, directed by author of Hebrews himself. Prof. Dr Gert Steyn, Department of New Testament Studies, Faculty of Theology, University of Introduction Pretoria. The relation between the text readings found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), those of the LXX witnesses and the quotations in Ad Hebraeos1 needs much more attention (Batdorf 1972:16–35; Corresponding author: 2 Gert Steyn, Bruce 1962/1963:217–232; Grässer 1964:171–176; Steyn 2003a:493–514; Wilcox 1988:647–656). -

Psalms 112-113 Page 1� of �7 M.K

Psalms 112-113 page 1! of !7 M.K. Scanlan Psalm 112 • Psalm 112 is a companion Psalm to Psalm 111. • It is also an acrostic Psalm with each verse or sentence beginning with a consecutive letter of the Hebrew alphabet. • This is one of the “hallel” psalms or Psalms of praise that either begins with or ends with “hallelujah!” • Psalm 111 ends with: (V: 10) Psalm 111:10 “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; a good understanding have all those who do His commandments. His praise endures forever.” • Psalm 111 ends with the reverence or fear of the Lord and the doing of His commandments. • Psalm 112 talks about the man who has learned what it is to stand in the awe and reverence of God, it’s about that man who has committed himself to obeying God and doing His commandments. V: 1 Praise the Lord! Hallelujah! Once again this could be both a proclamation and or an exhortation. • Blessed, or “Oh how happy” is the man who fears the Lord - why? Because if you learn to fear the Lord truly, you will ultimately end up getting saved! Proverbs 14:27 “The fear of the Lord is a fountain of life, to turn one away from the snares of death.” Proverbs 19:23 “The fear of the Lord leads to life,…” • If we fear God, then we don’t need to fear anything, or anyone else! Ecclesiastes 12:13 “Fear God and keep His commandments, for this is the whole duty of man.” • The antidote to depression, to un-happiness, anxiety, and fear - is to praise the Lord, to fear Him, and to joyfully be obedient to what He’s instructed us to do. -

Approach Toward Doctrine Church of God, a Worldwide Association

APPROACH TOWARD DOCTRINE CHURCH OF GOD, A WORLDWIDE ASSOCIATION he subject of doctrine is one of critical importance. Without an established doctrinal foundation everything else we accomplish would be of little value. We must ask ourselves, “If our doctrines are not correct, will anything else matter?” T We must be diligent in preserving the truth. We must not succumb to pressure to compromise the Word of God. Nor should we be unwilling to address the difficult doctrinal questions in an open and honest manner. Our approach must be humble and collaborative, not arrogant and isolated. We must begin with solid principles and proceed to the more difficult questions. We must confirm and re-establish our foundational beliefs that brought all of us together in the first place. In Ephesians 2:19-20 (NKJV) Paul states: “Now, therefore, you are no longer strangers and foreigners, but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, having been built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ Himself being the chief cornerstone.” Our foundation must be grounded in the Word of God, both the Old and New Testaments. Jesus Christ is the chief cornerstone of our beliefs and practices. Peter confirms this principle in II Peter 3:1-2: “This second epistle, beloved, I now write to you; in both which I stir up your pure minds by way of remembrance: That ye may be mindful of the words which were spoken before by the holy prophets, and of the commandment of us the apostles of the Lord and Saviour:” As a Church we must be well grounded in the truth. -

Psalms 111–112: Big Story, Little Story

religions Article Psalms 111–112: Big Story, Little Story Jack Collins Old Testament, Covenant Theological Seminary, 12330 Conway Road, St Louis, MO 63141, USA; [email protected] Academic Editors: Katharine J. Dell and Arthur J. Keefer Received: 10 May 2016; Accepted: 11 August 2016; Published: 5 September 2016 Abstract: This study argues that the juxtaposition of Psalms 111–112 offers wisdom for life. Psalm 111, in stressing God’s mighty deeds of redemption for his people, focuses on the “big story” for the whole people; Psalm 112, in stressing “wisdom,” encourages each member of God’s people in a day-to-day walk, a “little story,” that contributes to the big story of the whole people. Keywords: Proverbs; Psalms; Wisdom; story; community 1. Introduction To the larger consideration of how, if at all, Biblical wisdom literature provides resources for living in the contemporary world, I will focus on a small portion of the Psalms, namely Psalms 111–112 [1]. I write as a Christian, with an interest in how careful academic study might inform Christian practice. These two psalms are of quite different types. Psalm 111 celebrates the great works that the Lord has done: “he sent redemption to his people” (111:9). Psalm 112 celebrates the blessedness of the person “who fears the LORD” (112:1): “it is well with” such a person (112:5). Psalm 111 looks at the “big picture,” the deeds that the Lord has done for his “people,” that is, for the corporate entity. Psalm 112 attends primarily to the “smaller picture,” the conduct and effects of particular persons within the people. -

LESSON on PSALMS 107-129 September 18, 2019 Book Psalms

LESSON ON PSALMS 107-129 September 18, 2019 Book Psalms for Praying An Invitation to Wholeness by Nan C. Merrill History Israel understood its history to be a life of co-existence with God. It was a partnership with God centered on a historical event (the Exodus). At that time, God entered into a binding covenant relationship with the Israelites. In the course of time, God initiated something new when he made David to be their king. In Scripture we see how historical events (stories) showed God’s continual active presence. Most catastrophic event (end of Israel as a nation) was seen as God coming to judge. It was also interpreted as God coming to renew the people even through their suffering. Israelites were the first to discover the meaning of history as the epiphany of God. Israel was to be a partner with God in these events and to respond to his presence and activity. Emphasis was primarily on the actions of God. Old Testament showed that Israel did not keep silent about the mighty acts of God. People recalled the acts in historical writings and addressed God in a very personal way. People raised hymns of praise, boldly asked questions, and complained in the depths of distress. In this covenant relationship, Israel could converse with God. Finest example we have of this conversation with God is the Book of Psalms. It is a condensed account of the whole drama of the history of Israel. We have already noted that it is impossible to put them in their proper historical periods. -

1 Kings 2:10-12; 3:3-14; Psalm 111; Ephesians 5:15-20; John 6:51-58

Pentecost 12 Proper 15 (B) August 15, 2021 RCL: 1 Kings 2:10-12; 3:3-14; Psalm 111; Ephesians 5:15-20; John 6:51-58 1 Kings 2:10-12, 3:3-14 God writes straight with crooked lines, and Solomon certainly was a crooked line! Our reading today presents the idealized Solomon – humble, righteous, and God-fearing. After all, he is concerned foremost about serving God and being a wise ruler. But the context of our reading reveals that Solomon was a complicated man, with a but qualified love for God. The three verses preceding our lection remind us that Solomon brought a foreign wife to Jerusalem and worshipped at “high places” in violation of the Law, and first built a house for himself before building one for God. Subsequent history witnesses Solomon’s oppressive rule resulting in a split between the kingdoms of Judah and Israel. Rather than holding Solomon as a role model, we might interpret this narrative as an invitation to reflect upon God’s call to the imperfect, to the undeserving, and the flawed – in other words, to each of us. This is the mystery and miracle of God’s grace – we can’t do anything to become worthy of it but open our hearts and say yes to this gracious gift. • How have you experienced God’s grace through your flaws and imperfections? Psalm 111 Our psalm takes the form of a beautifully creative acrostic poem – each line begins with the next letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Within this literary architecture are timeless words of wisdom that nurture and nourish us on our journey toward holiness. -

140 Deliver Me, O Lord, from the Evil Man: Preserve Me from the Violent Man;

The Enemy of My Soul Psalms 140:1 -13 Psalms 140:1 Deliver me, O Lord, from the evil man: preserve me from the violent man; Romans 7:24 Oh wretched man that I am, who shall deliver me from the body of this death. Proverbs 18:21 Death and life are in the power of the tongues Psalms 140:2 -Which imagine mischief's in their heart; continually are they gathered together for war. James 4:1 - From whence come wars and fighting's among you? Come they not hence, even of your lusts that war in your members. Psalms140:3 - They have sharpened their tongues like a serpent; adders' poison is under their lips. Selah. James 3:8 But the tongues can no man tame, it is unruly evil, full of deadly poison. Psalms140:4 - Keep me, O Lord, from the hands of the wicked; preserve me from the violent man; who have purposed to overthrow my goings. Proverbs 6:2 You have been ensnared by the word of your mouth. Galatians 5:17 The flesh wars against the spirit and the spirit the flesh and these are contrary to one another so that you cannot do the things that you would. Psalms 140:5 - The proud have hid a snare for me, and cords; they have spread a net by the wayside; they have set gins for me. Selah. Mathew 12:36 But I say unto you, That every idle word that men shall speak, they shall give account thereof in the day of judgment. Mathew 12:37 The words you say now reflect your fate then; either you will be justified by them or you will be condemned. -

Editor's Notes for Beatus Vir

Editor’s Notes for Beatus Vir a 4 Beatus vir ("Blessed is the man” or “Happy are those”) are the first words in the Latin Vulgate Bible of both Psalm 1 and Psalm 112 (in the general modern numbering; it is Psalm 111 in the Vulgate). In each case, the words are used to refer to frequent and significant uses of these psalms in art, although the two psalms are prominent in different fields, art in the case of Psalm 1 and music in the case of Psalm 112. True to that tradition, Eslava used Psalm 112 for this piece, and it is the second version I have come across in my transcriptions of his work. Compare this to https://musescore.com/rebecca_rufin/beatus-vir-psalm-112-blessed-is-the-man or as also found in https://hilarioneslava.org/music/. This beautiful rendering of Beatus Vir is one of five choral works contained in a handwritten journal by Eslava. Although the title specifically reads “Beatus Vir a 4”, there are clearly eight singing parts that would appear to represent a double choir at first glance. No solo parts are formally indicated, but I surmise from the title that the first choir was most likely intended to be for solo voices. To the best of my knowledge, none of the works in this particular journal were ever formally published, and they all seem to lack composer’s instructions that would have been necessary to create the intended performance. Therefore, this work was likely never performed except under the direction of Eslava himself, who would have provided such instruction personally. -

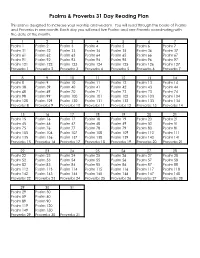

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Praise Ye Jehovah!

THE CANTATA SlNGERS SOPRANO ALTO MRS. JOSEPH BUGLIARI MISS SANDRA BAILEY MRS. KEITH CALKINS MRS. ROBERT CAMERON MRS. R. LEON CONSTANZER MPS. ALBERT CLARK MISS DIANNE DOWNER MISS MARJORIE COLE MRS. RICHARD DULUDE MRS. EDMUND DANA, JR. MISS MARY-ELLEN EARL MRS. ROBERT Fl NSTER MRS. R. EUGENE GOODSON MISS MARGARET HAHN MRS. SAMUEL HALE, JR. MISS KAY KENNEDY MRS. DONALD HOLTZ MRS. FREDER ICK LOOMIS MRS. JOHN HOOS MISS CAROL MANSFIELD MRS. ARTHUR MANSFIELD MRS . SAMUEL MINIER MISS CLARA BELLE PALMER MISS JUNE MORRONI MISS GAIL PRETTYMAN MRS. ROBERT SCHARF MRS. LESLIE READ SISTER MARTHA MARY MRS. JAMES REINSMITH SISTER MARY CHRISTOPHER MRS. ROBERT SAXTON SISTER MARY DOROTHY SISTER MARl E CECILE SISTER MARY SARTO SISTER MARY BERNARDINE SISTER MARY MAUREEN MISS GLENDA WILSON BASS TENOR MR. ROLAND BENTLEY MR. KEITH CALKINS MR. DeWITT BOTTS MR. R. LEON CONSTANZER MR. PAUL CLARK MR. EDMUND DANA, JR . FATHER SAMUEL HALE MR. RICHARD DeGEUS MR . JOHN KIHLSTROM MR. DAVID GARRETT MR. FREDER ICK PETRIE DR. R. EUGENE GOODSON MR. SIDNEY REED MR. PAUL JONES MR. MICHAEL SUSICK MR. JOHN RINDGE MR. RICHARD WACK THE QUARTET MRS. JAMES REINSMITH, so prano MISS KAY KE NNEDY, contralto MR. EDMUND DANA, JR., tenor MR. JAMES HUDSON, bass THE ORCHESTRA VIOLIN HORN MRS. ROBERT PERRY MR. JOHN KIHLSTROM MISS MARGARET MacDONNELL MR. BRUCE McCULLOUGH MR. KENNETH BROWN MISS BETH KOCHENAUR TRUMPET DR. C. BRENT OLDSTEAD DR. JAMES ODE MRS. THOMAS HUBBARD MR . ROGER ROSSI VIOLA TROMBONE MR. GEORGE ANDRIX MRS. EDWARD PETTENGILL MR. NORMAN WILCOX MR. ARTHUR LINSNER, JR. CELLO MR. FREDERICK BETSCHEN MR. FORREST SANDERS CONTRABASS TIMPANI MR.