Renewable Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C a Se Stud Y

This project is funded by the European Union November 2020 Culture in ruins The illegal trade in cultural property Case study: Algeria and Tunisia Julia Stanyard and Rim Dhaouadi Summary This case study forms part of a set of publications on the illegal trade in cultural property across North and West Africa, made up of a research paper and three case studies (on Mali, Nigeria and North Africa). This study is focused on Algeria and Tunisia, which share the same forms of material culture but very different antiquity markets. Attention is given to the development of online markets which have been identified as a key threat to this region’s heritage. Key findings • The large-scale extraction of cultural objects in both countries has its roots in the period of French colonial rule. • During the civil war in Algeria in the 1990s, trafficking in cultural heritage was allegedly linked to insurgent anti-government groups among others. • In Tunisia, the presidential family and the political elite reportedly dominated the country’s trade in archaeological objects and controlled the illegal markets. • The modern-day trade in North African cultural property is an interlinked regional criminal economy in which objects are smuggled between Tunisia and Algeria as well as internationally. • State officials and representatives of cultural institutions are implicated in the Algerian and Tunisian antiquities markets in a range of different capacities, both as passive facilitators and active participants. • There is evidence that some architects and real estate entrepreneurs are connected to CASE STUDY CASE trafficking networks. Introduction The region is a palimpsest of ancient material,7 much of which remains unexplored and unexcavated by Cultural heritage in North Africa has come under fire archaeologists. -

Potential Threats to Afro-Palearctic Migrato

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Unravelling the drastic range retraction of an emblematic songbird of North Africa: potential Received: 31 October 2016 Accepted: 16 March 2017 threats to Afro-Palearctic migratory Published: xx xx xxxx birds Rassim Khelifa1, Rabah Zebsa2, Hichem Amari3, Mohammed Khalil Mellal4, Soufyane Bensouilah3, Abdeldjalil Laouar5 & Hayat Mahdjoub1 Understanding how culture may influence biodiversity is fundamental to ensure effective conservation, especially when the practice is local but the implications are global. Despite that, little effort has been devoted to documenting cases of culturally-related biodiversity loss. Here, we investigate the cultural domestication of the European goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) in western Maghreb (Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia) and the effects of long-term poaching of wild populations (1990–2016) on range distribution, socio-economic value, international trading and potential collateral damage on Afro- Palearctic migratory birds. On average, we found that the European goldfinch lost 56.7% of its distribution range in the region which led to the increase of its economic value and establishment of international trading network in western Maghreb. One goldfinch is currently worth nearly a third of the average monthly income in the region. There has been a major change in poaching method around 2010, where poachers started to use mist nets to capture the species. Nearly a third of the 16 bird species captured as by-catch of the European goldfinch poaching are migratory, of which one became regularly sold as cage-bird. These results suggest that Afro-Palearctic migratory birds could be under serious by-catch threat. Species overexploitation for wildlife trade is a major global threat to biodiversity, particularly birds1, 2. -

Storage Map Lng

80.25 4.90 Petrozavodsk 39.25 7079 372 082 Huntorf L-gas N 3020 AUSTRIA 65.70 3.50 31.20 LATVIA 2320 SLOVAKIA 31.35 1071 Belgium, Zeebrugge 19.80 3.30Spain, Barcelona Turkey,11.64 Aliaga UK, Milford Haven SHTOKMAN UGS Láb complex 32.40 001 Schönkirchen / Reyersdorf 1544 236 N 083 Nüttermoor L-gas N Norway, Snøhvit Russia, Shtokman Pechora129 SeaIncukalns 2320 R 155 Russia, Yamal2365 LNG N Start-up : 1987 13.50 2.10Start-up : 1968 Start-up : 2006 South Hook LNG SNØHVIT (incl. Gajary baden) 24.50 ASKELADD Melkøya / Hammersfest Teriberka - Barents Sea Yamal Peninsula, north of Western Siberia 3.30 0.50 17.52 6.85 002 Tallesbrunn 347 53 N 084 Nüttermoor H-gas 541 N Start-up : 2009 MELKØYA Incukalns 3200 156 655 N 2.60 0.40 9.96 ALBATROSS Start-up : August 2007 Start-up : 2019 Láb IV 6.85 MAX. HOURLY CAPACITY NOM. ANNUAL CAPACITY MAX. HOURLY CAPACITY NOM. ANNUAL CAPACITY MAX. HOURLY CAPACITY NOM. ANNUAL CAPACITY Hammerfest Petrozavodsk Start-up : 2017 3 2.703 0.40 3 Nüttermoor-H : Storage3 Capacity connected to the Netherlands3 (GTS) 3 Salekhard 003 currentThann : 1.700.000 m (N)/h current217 : 9 bm (N)/year33 1.950.000N m (N)/h 17,1 bmE.ON (N)/year share of 109,3mcm solely used680.000 in NL m (N)/h 6,0 bm (N)/year MAX. HOURLY CAPACITY NOM. ANNUAL CAPACITY 31.50 2.40 0.30 3 3 LITHUANIA SPAIN 4103 3 3 3.36 2.440.000 m (N)/h 21 bm (N)/year 22.70 by 2015 : 2.150.000 m (N)/h by 2015 : 12 bm (N)/year2.88 085 Rüdersdorf H-gas 135 N 004 16. -

Diversity of Phytoplanktonic Populations Along the Algerian Coastline

Biodiversity Journal, 2019, 10 (2): 81–92 https://doi.org/10.31396/Biodiv.Jour.2019.10.2.81.92 Diversity of Phytoplanktonic populations along the Algerian coastline Mustapha Boudjenah1,2,*, Zakia Mokrane2 & Dina Soualili1 1Department of Marine Sciences and Aquaculture, Faculty of Natural Sciences and life, Abedelhamid Ibn Badis University, BP 227, Mostaganem, Algeria; e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2CNRDPA/National Center for Research and Development of Fisheries and Aquaculture, 11 Boulevard Amirouche, Bou- Ismail, Tipaza, Algeria; e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Phytoplankton biodiversity is the basis of the functioning of the aquatic ecosystems. Also, understanding and evaluating the effects of the change in our environment and their impact on planktonic populations is an important element. In fact, this paper was to appreciate the diversity and composition of phytoplankton in relation to some physicochemical parame- ters. Water samples were collected along the Algerian coastline (Alboran Sea, the Algerian basin and the Middle area), during the period May–June 2013. The study area contained a diversified phytoplankton community (296 species), belonging to 138 genera. The algal groups were represented and classified as dinoflagellates (180 species), diatoms (103 species), cyanophyceae, coccolithophorids, euglenids, and chrysophytes (13 species). The spatial distribution of cell densities revealed a heterogeneous phytoplankton composition dominated by dinoflagellates, which represent 63% of the total abundance, followed by di- atoms (35%). Quantitatively, we observed a highest cell density and diatoms abundance in most stations of the Alboran Sea decreasing towards the east (Algerian basin). The peak of dinoflagellates in June was represented by Prorocentrum and Gymnodinium genera. -

Atlas of the Ornamental and Building Stones of Volubilis Ancient Site (Morocco) Final Report

Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco) Final report BRGM/RP-55539-FR July, 2008 Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco) Final report BRGM/RP-55539-FR July, 2008 Study carried out in the framework of MEDISTONE project (European Commission supported research program FP6-2003- INCO-MPC-2 / Contract n°15245) D. Dessandier With the collaboration (in alphabetical order) of F. Antonelli, R. Bouzidi, M. El Rhoddani, S. Kamel, L. Lazzarini, L. Leroux and M. Varti-Matarangas Checked by: Approved by: Name: Jean FERAUD Name: Marc AUDIBERT Date: 03 September 2008 Date: 19 September 2008 If the present report has not been signed in its digital form, a signed original of this document will be available at the information and documentation Unit (STI). BRGM’s quality management system is certified ISO 9001:2000 by AFAQ. IM 003 ANG – April 05 Keywords: Morocco, Volubilis, ancient site, ornamental stones, building stones, identification, provenance, quarries. In bibliography, this report should be cited as follows: D. Dessandier with the collaboration (in alphabetical order) of F. Antonelli, R. Bouzidi, M. El Rhoddani, S. Kamel, L. Lazzarini, L. Leroux and M. Varti-Matarangas (2008) – Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco). BRGM/RP-55539-FR, 166 p., 135 fig., 28 tab., 3 app. © BRGM, 2008. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior permission of BRGM. Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis Synopsis The present study titled “Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis” was performed in the framework of the project MEDISTONE (“Preservation of ancient MEDIterranean sites in terms of their ornamental and building STONE: from determining stone provenance to proposing conservation/restoration techniques”) supported by the European Commission (research program FP6-2003-INCO-MPC-2 / Contract n° 015245). -

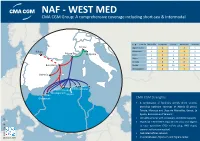

NAF - WEST MED CMA CGM Group: a Comprehensive Coverage Including Short-Sea & Intermodal

NAF - WEST MED CMA CGM Group: A comprehensive coverage including short-sea & Intermodal To From Marseilles La Spezia Genoa Barcelona Valencia Genoa Algiers ODCY 2 4 5 4 5 Bilbao Ghazaouet 2 4 5 4 5 Marseilles La Spezia Oran 2 4 5 4 5 Bejaia 6 8 9 8 9 Annaba 6 8 9 8 9 Barcelona Skikda 7 9 10 9 10 Mostaganem 2 4 5 4 5 Valencia Tunis Skikda Annaba Algiers Rouiba Mostaganem Oran Bejaia Ghazaouet CMA CGM Strengths • A combination of fixed-day weekly direct services providing optimum coverage of Algeria (8 ports), Tunisia, Morocco and Libya via Marseilles, Genoa, La Spezia, Barcelona and Valencia • Versatile services with containers and RORO capacity • Owned ALTERCO ODCY dry port in Rouiba, near Algiers to ease operations (150 reefers plug, IMO depot, scanner, railway connection) • Dedicated offices network www.cma-cgm.com October 2014 • Choice between Algiers dry and Algiers center NAF - WEST MED CMA CGM Group: A comprehensive coverage including short-sea & Intermodal Trieste Venice Genoa Ravenna CMA CGM Contacts Fos sur Mer La Spezia Ancona Livorno General Mailbox Vigo Civitavecchia [email protected] Barcelona Leixoes Naples Salerno Valencia Lisbon Gioia Tauro Bizerte Trapani Skikda Catania Algeciras Algiers Annaba Tunis Bejaia Djen Djen MALTA Oran Sfax TANGIER MED Ghazaouet Casablanca TUNISIA Tripoli Misurata Al Khoms Benghazi Agadir CMA CGM Strengths MOROCCO ALGERIA LIBYA • 9 weekly departures from Marseilles to NAF destinations • Two CMA CGM dedicated hubs: Malta and Tangier Med • Owned and dedicated feeder network from Malta ensuring weekly connections to 18 ports in the whole North Africa • Shuttle services deployed from Tangier Med to Oran, Ghazaouet, Tangier and Casablanca www.cma-cgm.com October 2014. -

Conflict Trends, Issue 1 (2015)

ISSUE 1, 2015 NORTH AFRICA The Thinker ACCORD is Ranked among Top Think Tanks in the World For the fi fth consecutive year, ACCORD has been recognised by the Global Go To Think Tank Index as one of the top-100 think tanks in the world. The 2014 Global Go To Think Tank Report was produced by the Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) at the University of Pennsylvania, USA. ACCORD is proud to have been ranked out of over 6 600 think tanks globally, of which 467 are based in sub-Saharan Africa, in the following sub-categories: • 32nd in the category ‘Top Think Tanks Worldwide (Non-US)’ (p. 62) and is the highest ranked African institution in this category • 63rd in the category 'Top Think Tanks Worldwide (US and Non-US) (p. 66) • 6th in the category 'Top Think Tanks in Sub-Saharan Africa' (p. 69) • 23rd in the category 'Best Managed Think Tanks' (p. 118) • 31st in the category 'Best Use of Social Networks' (p. 134). Global Distribution of Think Tanks by Region The 2014 GlobalThe 2014 Think Go Report Tank To 27.53% These rankings pay testament to ACCORD’s Knowledge Production, Interventions and Training 30.05% departments, which strive to produce both 16.71% experientially-based and academically rigorous knowledge, derived from our 23 years in the 7.87% confl ict resolution fi eld, relevant to practitioners, governments, civil society and organisations 10.18% within Africa and throughout the world. 7.06% Now in its eighth year, the Global Go To Think 0.59% Tank Index has become an authoritative resource for individuals and institutions worldwide. -

Specifications Guide Europe and Africa Refined Oil Products Latest Update: September 2021

Specifications Guide Europe And Africa Refined Oil Products Latest update: September 2021 Definitions of the trading locations for which Platts publishes daily indexes or assessments 2 LPG 4 Gasoline 7 Naphtha 9 Jet fuel 11 ULSD 13 Gasoil 16 Fuel oil 18 Feedstocks 23 Revision history 26 www.spglobal.com/platts Specifications Guide Europe And Africa Refined Oil Products: September 2021 DEFINITIONS OF THE TRADING LOCATIONS FOR WHICH PLATTS PUBLISHES DAILY INDEXES OR ASSESSMENTS The following specifications guide contains the primary specifications and methodologies for Platts refined oil products assessments throughout Europe and Africa. All the assessments listed here employ Platts Assessments Methodology, as published at https://www.spglobal.com/platts/plattscontent/_assets/_files/en/our-methodology/methodology-specifications/platts-assessments-methodology-guide.pdf. These guides are designed to give Platts subscribers as much information as possible about a wide range of methodology and specification questions. This guide is current at the time of publication. Platts may issue further updates and enhancements to this guide and will announce these to subscribers through its usual publications of record. Such updates will be included in the next version of this guide. Platts editorial staff and managers are available to provide guidance when assessment issues require clarification. Unnamed ship Seller has the responsibility to declare its Shipping considerations Northwest European and FOB Mediterranean oil product cargo commitment to meet either the vetting Bids: For the cargo assessment processes bids may be assessments reflect market activity where the seller nominates requirement of any buyer or conversely to expressed with a specific location. Bids with excessive the loading terminal 7 calendar days ahead of the first day of the declare up front how many ship vettings the limitations – whether expressed or implied – may be deemed 5-day laycan. -

Roman Art from the Louvre

Roman Art from the Louvre Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts Roman Art from the Louvre Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts Roman Art from the Louvre is organized by the American Federation of Arts and the Musée du Louvre. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity American Federation of Arts 305 East 47th Street, 10th floor from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. New York, NY 10017 212.988.7700 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes scholarly exhibition cata- logues, and develops educational materials and programs. © 2007 American Federation of Arts All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational purposes. Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x226 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary Indianapolis Museum of Art September 23, 2007–January 6, 2008 Seattle Art Museum February 21–May 11, 2008 Oklahoma City Museum of Art June 19–October 12, 2008 Design/Production: Emily Lessard Front cover: Fragment of a Relief of a Double Suovetaurilia Sacrifice (detail), 1st or 2nd quarter of 1st century A.D. (no. 4) Back cover: Knife Handle in the Shape of a Thracian Gladiator, 2nd half of 1st century A.D. (no. 6) CONTENTS About This Resource 4 Exhibition Overview 5 Ancient Roman Society 6 History of Ancient Rome Government—The Emperor and the Senate Citizenship Non-Citizens—Foreigners, Slaves, and Freedmen Leisure 10 The Baths Roman Theater Circus Maximus The Amphitheater Religion 11 Guide to Roman Gods and Goddesses 13 Guide to Roman Vessel Forms 16 Interesting Facts about Ancient Rome 18 Selected Works of Art 19 1. -

North Africa Issue 1, 2015

ISSUE 1, 2015 NORTH AFRICA The Thinker ACCORD is Ranked among Top Think Tanks in the World For the fi fth consecutive year, ACCORD has been recognised by the Global Go To Think Tank Index as one of the top-100 think tanks in the world. The 2014 Global Go To Think Tank Report was produced by the Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) at the University of Pennsylvania, USA. ACCORD is proud to have been ranked out of over 6 600 think tanks globally, of which 467 are based in sub-Saharan Africa, in the following sub-categories: • 32nd in the category ‘Top Think Tanks Worldwide (Non-US)’ (p. 62) and is the highest ranked African institution in this category • 63rd in the category 'Top Think Tanks Worldwide (US and Non-US) (p. 66) • 6th in the category 'Top Think Tanks in Sub-Saharan Africa' (p. 69) • 23rd in the category 'Best Managed Think Tanks' (p. 118) • 31st in the category 'Best Use of Social Networks' (p. 134). Global Distribution of Think Tanks by Region The 2014 GlobalThe 2014 Think Go Report Tank To 27.53% These rankings pay testament to ACCORD’s Knowledge Production, Interventions and Training 30.05% departments, which strive to produce both 16.71% experientially-based and academically rigorous knowledge, derived from our 23 years in the 7.87% confl ict resolution fi eld, relevant to practitioners, governments, civil society and organisations 10.18% within Africa and throughout the world. 7.06% Now in its eighth year, the Global Go To Think 0.59% Tank Index has become an authoritative resource for individuals and institutions worldwide. -

(National Legislation) © DOALOS/OLA

Page 1 Decree No. 84-181 of 4 August 1984 defining the baselines for measuring the breadth of the maritime zones under national jurisdiction ... Having regard to the Constitution, in particular article 111, paragraph 10, and article 152, Having regard to Decree No. 63-403 of 12 October 1963 establishing the extent of Algeria's territorial waters, ... Article 1 The breadth of the maritime zones under national jurisdiction, in particular the territorial sea, shall be measured from straight baselines and from lines enclosing bays. Article 2 The lines delimiting the maritime zones in question shall be defined by the following co-ordinates: I. From the Algerian-Moroccan frontier to Rachgoun Island (Algerian chart No. 1201) - From the Algerian-Moroccan frontier to Ras El Ouareye Rock (co-ord: 035° 06' 04" N - 002° 10' 02" W) - Ras El Ouareye Rock to Ras El Ouareye (co-ord: 035° 06' 12" N - 002° 09' 08" W) - Ras El Ouareye - Kef Bou Madane (co-ord: 035° 05' 44" N - 002° 06' 58" W) - Kef Bou Madane - Ras Kela (co-ord: 035° 04' 44" N - 002° 01' 10" W) - Ras Kela - Kef Riba (co-ord: 035° 05' 12" N - 001° 56' 03" W) - Kef Riba - Jetty Light (co-ord: 035° 06' 22" N - 001° 52' 03" W) - Jetty Light - Point west of Ras Tarsa (co-ord: 035° 07' 45" N - 001° 48' 54" W) - Poin t west of Ras Tarsa - Ras Chennaïra (co-ord: 035° 10' 45" N - 001° 41' 54" W) National legislation - DOALOS/OLA - United Nations asdf Page 2 II. Rachgoun Island to Mersat Medekh (Algerian chart No. -

ALGÉRIE =Æ Incendies Données D'analyse : 17 - 19 Juillet 2017 | Publiée : 20 Juillet 2017 | Version 1.0 FR20170712DZA

ALGÉRIE =Æ Incendies Données d'analyse : 17 - 19 juillet 2017 | Publiée : 20 juillet 2017 | Version 1.0 FR20170712DZA 1°40'0"E 2°30'0"E 3°20'0"E 4°10'0"E 5°0'0"E 5°50'0"E 6°40'0"E 7°30'0"E 8°20'0"E SPAIN Wilaya Nbre foyers Wilaya Nbre foyers 37°30'0"N Tipaza 19 El Tarf 3 Skikda 13 Tizi Ouzou 1 Algiers ¥¦¬ Constantine 5 Blida 1 MER MEDITERRANEE TUNISIA Jijel 4 Médéa 1 Collo Aperçu 1 Béjaïa 3 Chlef 1 Kala El Localisation de la carte Annaba Ain Defla 3 - - S k ikda )" ALGERIA )" S idiAmar J ijel Tamalous Annaba )" T izi-Ouzou Taher Azzaba Besbes )" Bejaia Milia El Drean Alger )" EmirAbdelkader Z eralda ¥¦¬ )" Harrouch El Alger 36°40'0"N Barak i Bou IsmaïlBou Boumerdès Tizi Ouzou Amizour Jijel Skikda El Tarf Densité des foyers d'incendies au nord de Cherchell 36°40'0"N Boufarik Larbâa Lak hdaria Béjaïa GraremGouga Guelma T énès MizanDraa El )" l'Algérie entre le 17 et le 19 juillet 2017 Kherrata Mila Akbou HammaBouziane Tipaza )" Ferdjioua Guelma Cettecarte densitéillustre la des foyers d'incendies détectés à Blida Aperçu 2 Bouira )" OuedZenati S oukAhras partirdes données MODISaccessibleNASA,de la via NASA )" )" Guenzet Constantine Miliana BessamAïn FIRMSavec unerésolution dansnord dekm,de l’Algérie le 1 DeflaAïn Medea Mila Taoura entre le 17 et le 19 juillet 2017. 54 foyers 54 étéont 2017. détectésjuillet 19 etentre le 17 le ChlefAttaf El )" S etif S edrata OuedFodda )" ChelghoumLaïd durantcette période quealorspériode au pourdula 14 allant Berrouaghia GhozlaneS ourEl Tadjenanet 16 juillet leurnombrejuillet 16 s’élevait Cette carteà99.