As I Began This Book, Many Americans Were Beginning to Be Cautious

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's Favorite Pastime

America’s favorite pastime Birmingham-Southern College has produced a lot exhibition games against major league teams, so Hall of talent on the baseball field, and Fort Worth Cats of Famers like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe shortstop Ricky Gomez ’03 is an example of that tal- DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Pee ent. Wee Reese,Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and Hank Gomez, who played on BSC’s 2001 NAIA national Aaron all played exhibition games at LaGrave Field championship team, is in his second year with the against the Cats. Cats, an independent professional minor league club. Gomez encourages BSC faithful to visit Fort Prior to that, he played for two years with the St. Worth to see a game or two. Paul Saints. “It is a great place to watch a baseball game and The Fort Worth Cats play in the Central Baseball there is a lot to do in Fort Worth.” League. The team has a rich history in baseball He also attributes much of his success to his expe- going back to 1888. The home of the Cats, LaGrave riences at BSC. Field, was built in 2002 at the same location of the “To this day, I talk to my BSC teammates and to old LaGrave Field (1926-67). Coach Shoop [BSC Head Coach Brian], who was Many famous players have worn the uniform of not only a great coach, but a father figure. the Cats including Maury Wills and Hall of Famers Birmingham-Southern has a great family atmos- Rogers Hornsby, Sparky Anderson, and Duke Snider. -

In, Lose, Or Draw Arcade Pontiac

SPORTS CLASSIFIED ADS P 7hl>1trttlT AvlA A A2) CLASSIFIED ADS JUNE 1951 ^t-UvIUIly JJU WEDNESDAY, 20, ** White Sox Finally Convince Yankees They re the Team to Beat I Holmes Preparing to Play About w or Draw Worrying in, Lose, as By FRANCIS STANN As Well Manage Braves DESPITE THOSE RUMORS that Billy Southworth may turn Wrong Fellows/ up with the Pirates next season, odds are that Billy is finished for keeps as a manager—just as Joe McCarthy is retired. Here were two of the best of all managers in their heydays, but they Stengel Thinks punished themselves severely. It’s odd, too, that .both careers were broken off in Boston. 60,441 Fans Thrilled They made a grim pair on the field. Maybe that’s why they were successful. McCarthy By Chicago's Rally won one pennant for the Cubs and eight for the To Split Twin Bill Yankees. Southworth won three pennants •y tha Associated Press in a row for the Cardinals, another for the Braves. When they were winning they were Those fighting White Sox ari tops' as managers. But adversity and advancing making believers of their oppo years eventually took their toll on the nervous nents—team by team, manager b; systems of these intense men. manager. McCarthy quit the Yankees in 1946 when Now it’s New York and Manage the third it became evident that, for straight Casey Stengel singing the praise to win. He sat on his year, he wasn’t going of the spectacular Sox. at Buffalo for two and was called porch years "Maybe we’ve been worryini back the Red Sox. -

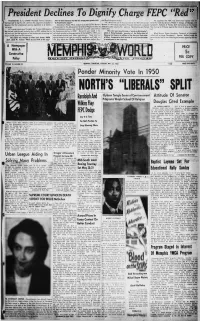

President Declines to Dignify Charge FEPC “Red

■ 1 —ft, President Declines To Dignify Charge FEPC “Red WASHINGTON, D. C.-(NNPA)-President Truman Saturday ment of some Senators that the fair employment practice bill and Engel,s began to write." | The argument that FEPC was Communist Inspired wai ve ) had declined to dignify with comment the argument of Southern is of Communist origin'** Mr. White was one of those present al the While House con hemently made by Senator* Walter F. George, of Georgia, and ference in 194) which resulted in President Roosevelt issuing an I Senator* that fair employment practice legislation is of Commu- According to Walter White, executive secretary of the Nation Spessard I. Holland, of Florida, both Democrats, on the Senate al Association for the Advancement of Colored People the fdea of I ni*t origin. executive aider creating the wartime fair Employment Practice floor during the filibuster ogaintl the motion to take up the FEPC At hi* press conference Thursday, Mr. Truman told reporters fair employment practices was conceived "nineteen years before Committee. ' bill. I that he had mode himself perfectly clear on FEPC, adding that he the Communists did so in 1928." He said it was voiced in the the order was issued to slop a "march on-Woshington", I did not know that the argument of the Southerners concerning the call which resulted in the organization of lhe NAACP in 1909, and which A. Philip Randolph, president of lhe Brotherhood of Whert Senotor Hubert Humphrey, Democrat, of Minnesota I origin of FEPC deserved any comment. that colored churches and other organizations "have cried out Sloeping Car Porters, an affiliate of lhe American Federation called such a charge ’ blasphemy". -

Bronx Bombers

BRONX BOMBERS BY ERIC SIMONSON CONCEIVED BY FRAN KIRMSER DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. BRONX BOMBERS Copyright © 2014, Eric Simonson All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of BRONX BOMBERS is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for BRONX BOMBERS are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Creative Artists Agency, 405 Lexington Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, NY 10174. -

Numbered Panel 1

PRIDE 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E The African-American Baseball Experience Cuban Giants season ticket, 1887 A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History Courtesy of Larry Hogan Collection National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 1 8 4 5 KNICKERBOCKER RULES The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club establishes modern baseball’s rules. Black Teams Become Professional & 1 8 5 0 s PLANTATION BASEBALL The first African-American professional teams formed in As revealed by former slaves in testimony given to the Works Progress FINDING A WAY IN HARD TIMES 1860 – 1887 the 1880s. Among the earliest was the Cuban Giants, who Administration 80 years later, many slaves play baseball on plantations in the pre-Civil War South. played baseball by day for the wealthy white patrons of the Argyle Hotel on Long Island, New York. By night, they 1 8 5 7 1 8 5 7 Following the Civil War (1861-1865), were waiters in the hotel’s restaurant. Such teams became Integrated Ball in the 1800s DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD DECISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BA S E BA L L PL AY E R S FO U N D E D lmost as soon as the game’s rules were codified, Americans attractions for a number of resort hotels, especially in The Supreme Court allows slave owners to reclaim slaves who An association of amateur clubs, primarily from the New York City area, organizes. R e c o n s t ruction was meant to establish Florida and Arkansas. This team, formed in 1885 by escaped to free states, stating slaves were property and not citizens. -

Black Diamond 1

Black Diamond 1 Black Diamond “The Greatest Stories Never Told” Series Recommended for Ages 6-11 Grades 1-6 A Reproducible Learning Guide for Educators This guide is designed to help educators prepare for, enjoy, and discuss Black Diamond It contains background, discussion questions and activities appropriate for ages 6-11. Programs Are Made Possible, In Part, By Generous Gifts From: D.C. Commission on the Arts & Humanities DC Public Schools The Nora Roberts Foundation Philip L. Graham Fund PNC Foundation Smithsonian Women's Committee Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program Sommer Endowment Discovery Theater ● P.O. Box 23293, Washington, DC ● www.discoverytheater.org Like us on Facebook ● Instagram: SmithsonianDiscoveryTheater ● Twitter: Smithsonian Kids Black Diamond 2 MEET SATCHEL PAIGE! Leroy “Satchel” Paige was born in Mobile, Alabama in 1906, the sixth of twelve children. His father was a gardener and his mother was a domestic worker. Some say Paige got his nickname while working as a baggage porter. He could carry so many suitcases (or satchels) at one time he looked like a “satchel tree.” At age 12, a truant officer caught Paige skipping school and stealing. As punishment, he was sent to industrial school. “It got me away from the bums.” He said later. “It gave me a chance to polish up my game. It gave me some schooling I’d of never taken if I wasn’t made to go to class.” PITCHING AND BARNSTORMING! Satchel Paige pitched his first Negro League game in 1924 with the semi-pro Mobile Tigers ball club. After a stretch with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, he went to the Kansas City Monarchs, helping them to win half a dozen pennants between the years 1939-1948. -

Grade 5 ELA Module 3A, Unit 2, Lesson 11

Grade 5: Module 3A: Unit 2: Lesson 11 Letters as Informational Text: Comparing and Contrasting Three Accounts about Segregation (Promises to Keep, Pages 38–39) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Exempt third-party content is indicated by the footer: © (name of copyright holder). Used by permission and not subject to Creative Commons license. GRADE 5: MODULE 3A: UNIT 2: LESSON 11 Letters as Informational Text: Comparing and Contrasting Three Accounts about Segregation (Promises to Keep, Pages 38–39) Long-Term Targets Addressed (Based on NYSP12 ELA CCLS) I can determine the main idea(s) of an informational text based on key details. (RI.5.2) I can determine the meaning of academic words or phrases in an informational text. (RI.5.4) I can determine the meaning of content words or phrases in an informational text. (RI.5.4) I can compare and contrast multiple accounts of the same event or topic. (RI.5.6) Supporting Learning Targets Ongoing Assessment • I can describe how the text features of a letter help readers. • Three Perspectives Venn diagram • I can compare and contrast three different points of view (Jackie Robinson’s, his wife’s, and his • Journals (synthesis writing) daughter’s) of the same event. • I can determine the meaning of new words and phrases from context in the book Promises to Keep. Copyright © 2013 by Expeditionary Learning, New York, NY. All Rights Reserved. NYS Common Core ELA Curriculum • G5:M3A:U2:L11 • June 2014 • 1 GRADE 5: MODULE 3A: UNIT 2: LESSON 11 Letters as Informational Text: Comparing and Contrasting Three Accounts about Segregation (Promises to Keep, Pages 38–39) Agenda Teaching Notes 1. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Jackie Robinson

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 3-4-1998 Jackie Robinson Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "Jackie Robinson" (1998). On Sport and Society. 499. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/499 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR ARETE March 4, 1998 It has been the year to remember the achievements of Jackie Robinson both in and outside of baseball. Robinson's breaking of the color line had a social significance which transcended the game of baseball. At the season opener at Shea Stadium the President of the United States recognized Jackie Robinson, and the Acting Commissioner of Baseball retired Jackie's number for all of major league baseball. Radio and TV programs have examined the events of 1947, social commentators have recalled Robinson's contributions to American life, and baseball historians have paid their tributes to this remarkable man. At baseball's annual All-Star game next week in Cleveland, the man who broke the color line in the American League and in Cleveland will finally receive some of the recognition he deserves. -

Baseball Cards of the 1950S: a Kid’S View Looking Back by Tom Cotter CBS and NBC All Broadcast Televised Games in the 1950S and On

Like us and Devoted to Antiques, follow us Collectibles, on Furniture, Art and Facebook Design. May 2017 EstaBLIshEd In 1972 Volume 45, number 5 Baseball Cards of the 1950s: A Kid’s View Looking Back By Tom Cotter CBS and NBC all broadcast televised games in the 1950s and on. 1950 saw the first televised All-Star game; 1951 While I am not sure what got us started, about 1955 the premier game in color; 1955 the first World Series in we began collecting baseball cards (my brother was eight, color (NBC); 1958 the beginning televised game from the I was five). I suspect it was reasonably inexpensive and West Coast (L.A. Dodgers at S.F. Giants with Vin Scully we were certainly in love with baseball. We lived in Wi - announcing); and 1959 the number one replay (requested chita, Kansas, which in the 1950s had minor league teams by legend Mel Allen of his producer.) In 1950, all 16 (Milwaukee Braves AAA affiliate 1956-1958), although I Major League teams were from St. Louis to the East Coast don’t recall that we went to any games. However, being and mostly trains were used for travel. The National somewhat competitive and playing baseball all summer, League contained: Boston Braves, New York Giants, we each chose a team to root for and rather built our base - Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, Pittsburg Pirates, ball card collections around those teams. My brother’s Cincinnati Redlegs (1953-1960 no “Reds” during the Mc - favorite team was the Chicago Cubs, with perennial All- Carthy Era), Chicago Cubs, and St. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3.