The 1940 Norway Campaign Showed How Modern Warfare Would Require Airpower and Joint Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PD GLADIATORS FITNESS NETWORK - SAMPLE SCHEDULE Now Operated by the Parkinson's Foundation

PD GLADIATORS FITNESS NETWORK - SAMPLE SCHEDULE Now Operated by the Parkinson's Foundation Classes Instructor Location Facility MONDAY 10:45am - 11:45am Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff East Lake East Lake Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:00 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Newnan Summit Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:15 pm Optimizing Exercise (1st and 3rd M) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 11:00 am - 12:15 pm Boxing Training for PD (I/II) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 11:15 am - 12:10 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Canton G. Cecil Pruett Comm. Center Family YMCA 11:30 am - 12:25 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Chamblee Cowart Family/Ashford Dunwoody YMCA 11:35 am - 12:25 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Lawrenceville J.M. Tull-Gwinnett Family YMCA 12:00pm - 12:45pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Cumming Forsyth County Family YMCA 12:30 pm - 1:30pm Boxing Training for PD (III/IV) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 1:00 pm - 1:30 pm PD Group Cycling YMCA Staff Cumming Forsyth County Family YMCA 1:20pm - 2:15pm PD Group Cycling YMCA Staff Alpharetta Ed Isakson/Alpharetta Family YMCA 2:30 pm - 3:30 pm Knock Out PD - Boxing TITLE Boxing Staff Kennesaw TITLE Boxing Club Kennesaw 7:00 pm - 8:00 pm Dance for Parkinson's Paulo Manso de Sousa Newnan Southern Arc Dance TUESDAY 10:30 am - 11:15 am Dance for Parkinson's Paulo Manso de Sousa Newnan Southern Arc Dance 10:30 am - 11:30 am Ageless Grace Lori Trachtenberg Vinings Kaiser Permanente (members only) 10:30 am - 11:15 am Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Covington Covington Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:00 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Decatur South DeKalb Family YMCA 11:00 am - 12:15 pm Boxing Training for PD (I/II) LDBF Sandy Springs Fitness Firm 11:30 am - 12:00 pm PD Group Cycling YMCA Staff Kennesaw Northwest Family YMCA 12:00 pm - 1:00 pm Dance for Parkinson's Eleanor/Rob Rogers Cumming Still Pointe Dance Studios 12:15 pm - 12:45 pm Parkinson's Movement Class YMCA Staff Buckhead Carl E. -

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

The Nickel Mineralizationof the Rana Mafic Intrusion, Nordland, Norway

• THE NICKEL MINERALIZATIONOF THE RANA MAFIC INTRUSION, NORDLAND, NORWAY. Rognvald Boyd and Carl 0. Mathiesen Norges geologiskeundersøkelse,Postboks 3006, 7001 Trondheim, Norway. NORGES GEOLOGISKE UNDERSØKELSE ABSTRACT The Råna synorogenicCaledonide intrusion in north Norway contains pentlandite+pyrrhotite+chalcopyrite+pyritedisseminationsgrading up tO 0.8% sulfide nickel in peridotite in the northwesternpart of the body. Peridotite and pyroxenite occur as bands and lenses within a peripheral zone mainly of norite, around a core mainly of quartz-norite.Crystal settling appears to have been an important process at Råna but over much of the intrusion primary structureshave been severely disturbed by the later Caledonian fold phases which also involved local overthrusting: these movements resulted in iniolding and thrustingof units of semipel- itic and calesilicate gneiss and black schist into the intrusion.The body has the form of an inverted, possibly truncated cone with its axiS plunging northwestwardsat a moderate angle. The peridotites show no obvioUs systematicvariation of sulfide or silicate mineralogy across strike. Locally, ass&iated with certain deformation zones, disseminationpasses into ma3sive mobilized sulfide ti with up to 5% nickel. The proximity of sulfide-bearingblack schists to mineralized rocks, the occurrence of graphite djsseminated in peridotite and other factors, suggest assimilationof sulfur from the Country rocks. Sulfur isotope studies do not, however, offer confirmationof the hypo- thesis that an external source ot sulfur nas had more than very local significanceat Råna. 1 NORGES GEOLOGISKE UNDERSØKELSE • INTRODUCTION The Råna mafic intrusion lies at approximately68°30'N, in steep mountainous terrain 20 km soutnwest of the iron-ore port of Narvik in north Norway (Fig.1).The present paper will give a brief description of the general geology of the complex, with a more detailed consider- ation of the sulfide-bearingareas - especially the main one at Bruvann (Fig.2) - and of the cenetic implicationsinvolved. -

The Heroic Destroyer and "Lucky" Ship O.R.P. "Blyskawica"

Transactions on the Built Environment vol 65, © 2003 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 The heroic destroyer and "lucky" ship O.R.P. "Blyskawica" A. Komorowski & A. Wojcik Naval University of Gdynia, Poland Abstract The destroyer O.R.P. "Blyskawica" is a precious national relic, the only remaining ship that was built before World War I1 (WW2). On the 5oth Anniversary of its service under the Polish flag, it was honoured with the highest military decoration - the Gold Cross of the Virtuti Militari Medal. It has been the only such case in the whole history of the Polish Navy. Its our national hero, war-veteran and very "lucky" warship. "Blyskawica" took part in almost every important operation in Europe throughout WW2. It sailed and covered the Baltic Sea, North Sea, all the area around Great Britain, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. During the war "Blyskawica" covered a distance of 148 thousand miles, guarded 83 convoys, carried out 108 operational patrols, participated in sinking two warships, damaged three submarines and certainly shot down four war-planes and quite probably three more. It was seriously damaged three times as a result of operational action. The crew casualties aggregated to a total of only 5 killed and 48 wounded petty officers and seamen, so it was a very "lucky" ship during WW2. In July 1947 the ship came back to Gdynia in Poland and started training activities. Having undergone rearmament and had a general overhaul, it became an anti-aircraft defence ship. In 1976 it replaced O.R.P. "Burza" as a Museum-Ship. -

Ski Touring in the Narvik Region

SKI TOURING IN THE NARVIK REGION TOP 5 © Mattias Fredriksson © Mattias Narvik is a town of 14 000 people situated in Nordland county in northern Norway, close to the Lofoten islands. It is also a region that serves as an excellent base for alpine ski touring and off-piste skiing. Here, you are surrounded by fjords, islands, deep valleys, pristine lakes, waterfalls, glaciers and mountain plateaus. But, first and foremost, wild and rugged mountains in seemingly endless terrain. Imagine standing on one of those Arctic peaks admiring the view just before you cruise down on your skis to the fjord side. WHY SKI TOURING IN THE NARVIK REGION? • A great variety in mountain landscapes, from the fjords in coastal Norway to the high mountain plateaus in Swedish Lapland. • Close to 100 high quality ski touring peaks within a one- hour drive from Narvik city centre. • Large climate variations within short distances, which improves the chances of finding good snow and weather. • A ski touring season that stretches from the polar night with its northern lights, to the late spring with never- ending days under the midnight sun. • Ascents and descents up to 1700 metres in vertical distance. • Some of the best chute skiing in the world, including 1200-metre descents straight down to the fjord. • Possibilities to do train accessed ski touring. • A comprehensive system of huts that can be used for hut-to-hut ski touring or as base camps. • 5 alpine skiing resorts within a one-hour car drive or train ride • The most recognised heli-skiing enterprise in Scandinavia, offering access to over 200 summits. -

UCLA Historical Journal

UCLA UCLA Historical Journal Title Protestant "Righteous Indignation": The Roosevelt Vatican Appointment of 1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0bv0c83x Journal UCLA Historical Journal, 17(0) ISSN 0276-864X Author Settje, David Publication Date 1997 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 124 UCLA Historical Journal Protestant "Righteous Indignation": The Roosevelt Vatican Appointment of 1940 David Settje C t . ranklin D. Roosevelt's 1940 appointment of a personal representative / * to the Vatican outraged most Protestant churches. Indeed, an / accounting of the Protestant protests regarding the Holy See appointment reveals several aspects of American religious life at that time. As the United States moved closer to becoming a religiously plurahstic society and shed its Protestant hegemony, mainline Protestant churches sought to maintain leverage by denouncing any ties to the Vatican. Efforts to avert this papal affiliation also stemmed from traditional American anti-Cathohcism. Therefore, the attempt to preserve Protestant influence with anti-Catholic rhetoric against a Vatican envoy demonstrates how mainline churches want- ed to sway governmental pohcy, even in the area of foreign affairs. Protestant churches asserted that they were defending the principle of the separation of church and state. But an inspection of their protests against the Vatican appointment illustrates that they were also concerned about how such repre- sentation would affect their place in U.S. society and proves that they still dis- trusted Catholicism. In short, although they cloaked their arguments in the guise of defending the separation of church and state, the Vatican appoint- ment became a forum in which Protestant denominations displayed their anxiety about the development of religious pluralism in America, voiced tra- ditional anti-Catholicism, and ultimately influenced diplomatic policy. -

Tyranny Could Not Quell Them

ONE SHILLING , By Gene Sharp WITH 28 ILLUSTRATIONS , INCLUDING PRISON CAM ORIGINAL p DRAWINGS This pamphlet is issued by FOREWORD The Publications Committee of by Sigrid Lund ENE SHARP'S Peace News articles about the teachers' resistance in Norway are correct and G well-balanced, not exaggerating the heroism of the people involved, but showing them as quite human, and sometimes very uncertain in their reactions. They also give a right picture of the fact that the Norwegians were not pacifists and did not act out of a sure con viction about the way they had to go. Things hap pened in the way that they did because no other wa_v was open. On the other hand, when people acted, they The International Pacifist Weekly were steadfast and certain. Editorial and Publishing office: The fact that Quisling himself publicly stated that 3 Blackstock Road, London, N.4. the teachers' action had destroyed his plans is true, Tel: STAmford Hill 2262 and meant very much for further moves in the same Distribution office for U.S.A.: direction afterwards. 20 S. Twelfth Street, Philadelphia 7, Pa. The action of the parents, only briefly mentioned in this pamphlet, had a very important influence. It IF YOU BELIEVE IN reached almost every home in the country and every FREEDOM, JUSTICE one reacted spontaneously to it. AND PEACE INTRODUCTION you should regularly HE Norwegian teachers' resistance is one of the read this stimulating most widely known incidents of the Nazi occu paper T pation of Norway. There is much tender feeling concerning it, not because it shows outstanding heroism Special postal ofler or particularly dramatic event§, but because it shows to new reuders what happens where a section of ordinary citizens, very few of whom aspire to be heroes or pioneers of 8 ~e~~ 2s . -

Gladiators Handout

Gladiators Handout Who were gladiators? Mostly unfree individuals such as condemned criminals, prisoners or war, slaves. Some were volunteers (freedmen or low class free-born men) who did it for fame and money. Women could be gladiators – called Gladeatrix – but these were rare. Different types of gladiatorial games • Animals in the arena - Venationes • Executions • Man vs man Q. What is the name of the arena (above) recreated for the film Gladiator (2000)? Q. How many people could it hold and when was it built? Types of gladiators Gladiators were distinguished by the kind of armour they wore, the weapons they used and their style of fighting. • Eques These would begin on horseback and usually finish fighting in hand-to-hand combat. • Hoplomachus These were heavy-weapons fighters who fought with a long spear and dagger. • Provocator These were attackers who were usually heavily armed. Generally, they were slower and less agile than the other fighters listed above. They wore pectoral covering the vulnerable upper chest, padded arm protector and one greave on his left leg. • Retiarius These were known as “net-men”, i.e. they fought with a net with a long trident and small dagger. They were the quickest and most mobile of all the fighters. They fought with practically no armour that made them more vulnerable to serious injuries during fights. • Bestiarius These were individuals who were trained to fight against wild animals such as tigers and lions. Mostly criminals were sentenced to fight in this role, they, however, would not be trained nor armed. They were the least popular of all the gladiator fighters. -

The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs

Jeremy Stöhs ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Jeremy Stöhs is the Deputy Director of the Austrian Center for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies (ACIPSS) and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, HOW HIGH? Kiel University. His research focuses on U.S. and European defence policy, maritime strategy and security, as well as public THE FUTURE OF security and safety. EUROPEAN NAVAL POWER AND THE HIGH-END CHALLENGE ISBN 978875745035-4 DJØF PUBLISHING IN COOPERATION WITH 9 788757 450354 CENTRE FOR MILITARY STUDIES How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge Djøf Publishing In cooperation with Centre for Military Studies 2021 Jeremy Stöhs How High? The Future of European Naval Power and the High-End Challenge © 2021 by Djøf Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior written permission of the Publisher. This publication is peer reviewed according to the standards set by the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. Cover: Morten Lehmkuhl Print: Ecograf Printed in Denmark 2021 ISBN 978-87-574-5035-4 Djøf Publishing Gothersgade 137 1123 København K Telefon: 39 13 55 00 e-mail: [email protected] www. djoef-forlag.dk Editors’ preface The publications of this series present new research on defence and se- curity policy of relevance to Danish and international decision-makers. -

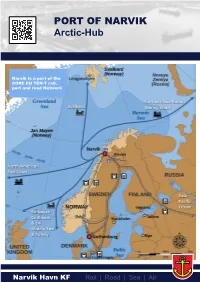

PORT of NARVIK Arctic-Hub

PORT OF NARVIK Arctic-Hub Narvik is a part of the CORE EU TEN-T rail, port and road Network 1 Arctic-Hub The geographic location of Narvik as a hub/transit port is strategically excellent in order to move goods to and from the region (north/south and east/west) as well as within the region itself. The port of Narvik is incorporated in EU’s TEN-T CORE NETWORK. On-dock rail connects with the international railway network through Sweden for transport south and to the European continent, as well as through Finland for markets in Russia and China. Narvik is the largest port in the Barents Region and an important maritime town in terms of tonnage. Important for the region Sea/port Narvik’s location, in relation to the railway, road, sea and airport, Ice-free, deep sea port which connects all other modes of makes the Port of Narvik a natural logistics intersection. transport and the main fairway for shipping. Rail Airport: The port of Narvik operates as a hub for goods transported by Harstad/Narvik Airport, Evenes is the largest airport in North- rail (Ofotbanen) to this region. There are 19 cargo trains, in ern Norway and is one of only two wide body airports north each direction (north/south), moving weekly between Oslo and of Trondheim. Current driving time 1 hour, however when the Narvik. Transportation time 27 hours with the possibility of Hålogaland Bridge opens in 2017, driving time will be reduced making connections to Stavanger and Bergen. to 40 minutes. The heavy haul railway between Kiruna and Narvik transports There are several daily direct flights from Evenes to Oslo, 20 mt of iron ore per year (2015). -

Effects-Based Operations and the Law of Aerial Warfare

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 5 Issue 2 January 2006 Effects-based Operations and the Law of Aerial Warfare Michael N. Schmitt George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Michael N. Schmitt, Effects-based Operations and the Law of Aerial Warfare, 5 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 265 (2006), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Global Studies Law Review VOLUME 5 NUMBER 2 2006 EFFECTS-BASED OPERATIONS AND THE LAW OF AERIAL WARFARE MICHAEL N. SCHMITT* Law responds almost instinctively to tectonic shifts in warfare.1 For instance, the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 constituted a dramatic reaction to the suffering of civilian populations during World War II.2 Similarly, the 1977 Protocols Additional3 updated and expanded the law of armed conflict (LOAC) in response both to the growing prevalence of non-international armed conflicts and wars of national liberation and to the recognized need to codify the norms governing the conduct of hostilities.4 In light of this symbiotic relationship, it is essential that LOAC experts carefully monitor developments in military affairs, because such developments may well either strain or strengthen aspects of that body of law.5 As an example, the widespread use in Iraq of civilian contractors and * Professor of International Law and Director, Program in Advanced Security Studies, George C.