Lewes Historic Character Assessment Report Pages 28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Designs Through History: from Simple Mounds to Strong Towers

https://www.exploring-castles.com/castle_designs/ Castle Designs Through History: From Simple Mounds to Strong Towers Castle designs have changed over history. This is because of changes in technology over time – as well as changes to the function and purpose of castles. The first castles were simply ‘mounds’ of earth, and medieval castle designs improved on these basics – adding ditches in the Motte & Bailey design. As technology advanced – and as attackers got more sophisticated – elaborate concentric castle designs emerged, creating a fortress almost impregnable to its enemies. Nowadays, castles are designed for prestige, for fantasy, and to embellish a romantic view of the life of kings, queens and nobles from years gone by. This page gives a brief overview of the history of castles, and explains why different castle designs came about. Fundamentally, these changing designs were due to the changes in the purpose and significance of castles. Early Medieval Times From Norman Times: Motte & Bailey Castles – Simple designs that were quick to build The first castles, built in the Early Middle Ages (early Medieval period), were ‘earthworks’ – mounds of earth primarily built for defence, as enemies struggled to climb them. During the 1000s, the Normans developed these into Motte and Bailey castle designs. Effectively, a ‘Motte’ was a large mound of earth, and a ‘Bailey’ was the flattened area beside the mound. The ‘Motte’ could be surrounded with a ditch, and buildings could be placed on the bailey – made of timber or, if time permitted, stone. The key benefit of Motte & Bailey castles was that they were very quick to build, but pretty difficult to attack. -

Shell Keeps-Catalogue1

Shell-keeps - The Catalogue Fig. 1. Plan of Berkeley Castle prepared for G. T Clark, published in Vol. 1 of Mediaeval Military Architecture, 1884, opposite. p. 229. Berkeley 2. Berkeley er (knocking out an earlier “bastion”) comprising two, Published interpretations of the shell-keep have as- joined rectangular towers which may be an early ex- sumed the following sequence: (a) the motte was part ample of an artillery emplacement and (ii) additions of the castle of William fitzOsbern, documented in and alterations to the forebuilding and (iii) encasement the late 11th century, bearing a structure of which no of the south “bastion” by the new gatehouse to the trace now remains; (b) with the assent and direction inner bailey (e) the siege of 1645 and the slighting of of Henry II in 1154, the new owner, Robert fitzHard- 1646 inflicted damage to the motte and its masonry ing (a rich Bristol merchant, from an English family, structures which were patched up around 1700 (f) who supported the Angevin cause and died in 1170) various 18th- to 20th-century alterations and additions truncated the motte-top, encased the motte in a shell- further masked and/or destroyed the structures, both in keep with battered plinth, a series of pilaster buttress- the domestic ranges (the east range of which is wholly es, (probably) four semi-circular “bastions” and (soon 1920s, as is the rebuilding of the chapel) and in Thor- afterwards) a forebuilding with defended stair rising pe's Tower. from ground level to a doorway on the motte-top, the The castle is unusual in having charter evidence latter being leveled up with the spoil created by relating to its revival under new ownership in the truncating the motte; (c) this shell-keep rose above 1150s, although the authenticity of these charters as the motte, with domestic buildings against its inside contemporary record has been questioned. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

Shell Keeps at Carmarthen Castle and Berkeley Castle

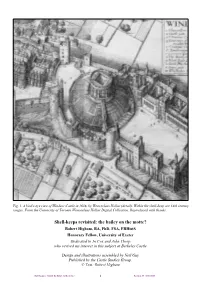

Fig. 1. A bird's-eye view of Windsor Castle in 1658, by Wenceslaus Hollar (detail). Within the shell-keep are 14th century ranges. From the University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection. Reproduced with thanks. Shell-keeps revisited: the bailey on the motte? Robert Higham, BA, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Honorary Fellow, University of Exeter Dedicated to Jo Cox and John Thorp, who revived my interest in this subject at Berkeley Castle Design and illustrations assembled by Neil Guy Published by the Castle Studies Group. © Text: Robert Higham Shell-keeps re-visited: the bailey on the motte? 1 Revision 19 - 05/11/2015 Fig. 2. Lincoln Castle, Lucy Tower, following recent refurbishment. Image: Neil Guy. Abstract Scholarly attention was first paid to the sorts of castle ● that multi-lobed towers built on motte-tops discussed here in the later 18th century. The “shell- should be seen as a separate form; that truly keep” as a particular category has been accepted in circular forms (not on mottes) should be seen as a academic discussion since its promotion as a medieval separate form; design by G.T. Clark in the later 19th century. Major ● that the term “shell-keep” should be reserved for works on castles by Ella Armitage and A. Hamilton mottes with structures built against or integrated Thompson (both in 1912) made interesting observa- with their surrounding wall so as to leave an open, tions on shell-keeps. St John Hope published Windsor central space with inward-looking accommodation; Castle, which has a major example of the type, a year later (1913). -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

IN SUSSEX ARTHUR STANLEY COOKE Witti One Hundred and Sixty Illustrations by Sussex Artists

OFF THE BEATEN TRACK IN SUSSEX ARTHUR STANLEY COOKE Witti one Hundred and sixty illustrations by Sussex artists :LO ICNJ :LT> 'CO CD CO OFF THE BEATEN TRACK IN SUSSEX BEEDING LEVEL. (By Fred Davey ) THE GATEWAY, MICHELHAM PRIORY (page 316). (By .4. S. C.) OFF THE BEATEN TRACK IN SUSSEX BY ARTHUR STANLEY COOKE WITH ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY ILLUSTRATIONS BY SUSSEX ARTISTS IN CUCKFIELD PARK (By Walter Puttick.) HERBERT JENKINS LIMITED 3 YORK STREET LONDON S.W. i A HERBERT JENKINS' BOOK Printed in Great Britain by Wyman & Sons Ltd., London, Reading and Fakenham, BOSHAM (page 176). (By Hubert Schroder, A.R.E.) PREFACE this volume tends to make our varied and beautiful county " " better known, it shall do well especially if it gives pleasure to those unable to take such walks. If it has, IF here and there, a thought or an idea not generally obvious, it may perhaps be forgiven the repetitions which are inevitable in describing similar details forgiven the recital of familiar facts, whether historical, archaeological or natural forgiven, where, by the light of later or expert knowledge, errors are apparent. Some of these blemishes are consequent on the passage of time necessary to cover so large an area by frequent personal visitation. Some thirty-seven rambles are described, about equally divided between the east and west divisions of the county. Although indications of route are given, chiefly for the benefit of strangers, it does not claim to be a guide-book. Its size would preclude such a use. Neither does it pretend to be exhaustive. -

The Norman Conquest Learning Objective: to Understand Chronology, Sources and Factors Through the History of the Norman Conquest of England

Year 7) Term 2A: The Norman Conquest Learning objective: To understand chronology, sources and factors through the history of the Norman Conquest of England. What do I need to know about William and his coronation as king? KEYWORDS: • The coronation of William of Normandy on Christmas Day 1066. Chronology = events put in the • How Anglo-Saxon people reacted to the new Norman king. order that they happened. • What William wanted to do next. Sources = evidence from the past. What do I need to know about the Norman Conquest? Interpretations = a persons • How William created a Feudal System hierarchy. opinion on a historical event. • How William used the Domesday Book to collect information. Key events/people: • How William created Motte & Bailey Castles to scare the English. William the Conqueror/William • How the Bayeux Tapestry controlled history. of Normandy The Feudal System What do I need to know about the Harrying of the North? The Domesday Book • Why William decided to launch an attack on the North. Motte & Bailey Castles • What tactics William used when attacking the North. The Bayeux Tapestry • How England changed under the reign of William of Normandy. The Harrying of the North 25 December 1066 AD 1067-86 AD 1069 AD William is coroneted as Motte & Bailey castles are created and William launches an assault on the Northern rebels: The King of England. the Domesday Book is completed. Harrying of the North begins and ends. What first-order concepts do I need to learn below? Hint: remember! A first-order concept is a word historians use to describe facts related to events. -

XXXI. a Few Remarks on the Discovery of the Remains Of

430 XXXI. A few Remarks on the Discovery of the Remains of William de Warren, and his wife Gundrad, among the ruins of the Priory of Saint Pancras, at Southover, near Lewes, in Sussex. By GIDEON ALGERNON MANTELL, Esq. LL.D., FR.S., fyc, in a Letter to Sir HENKY ELLIS, K.H., FR.S, Secretary. Read 11th Dec. 1845. IT is not a little remarkable that so few objects of geological, or antiquarian, interest should hitherto have been brought to light, by the excavations and cuttings made, during the formation of the numerous lines of railway, in various parts of England. Extensive as are these operations, the accessions to the collection of the geologist, and to the cabinet of the antiquary, have been comparatively unimportant. The most interesting archaeological dis- covery effected by the railway cuttings, is unquestionably that which took place, about six weeks since, in the ruins of Lewes Priory; namely, of the two leaden coffers, containing the remains of the founder and foundress of that once celebrated religious establishment. To me, who in early boyhood had so often rambled among those ruins in quest of some relic of the olden time, and, in maturer years, had caused excavations to be made in various places, in the hope of discovering the graves of some of the illustrious dead which history instructs us were buried within the hallowed walls of this priory, the announcement of this discovery was peculiarly gratifying. Having visited the spot, and examined the relics that have been exhumed, it occurred to me that a brief notice of a few particulars that came under my observation, with some account of the Norman pavements which I dug up, many years since, near the place where the coffers were discovered, might, under existing circumstances, possess at least a temporary interest. -

Piddinghoe Conservation Area Appraisal

In May 2007 Lewes District Council approved this document as planning guidance and therefore it will be a material consideration in the determination of relevant planning applications. Acknowledgements With thanks to Valerie Mellor, who showed me around the village, and who lent me her book Portrait of Piddinghoe 1900-2000 – an invaluable help with this document. This document has been written and illustrated by: The Conservation Studio, 1 Querns Lane, Cirencester, Glos GL7 1RL. Tel: 01285 642428 Email: [email protected] Website: www.theconservationstudio.co.uk Contents: Page 1 Summary 1 1.1 Key positive characteristics 1 1.2 Recommendations 1 2 Introduction 2 2.1 The Piddinghoe Conservation Area 2 2.2 The purpose of a conservation area character appraisal 2 2.3 The planning policy context 3 2.4 Community involvement 3 3 Location and landscape setting 4 3.1 Location and activities 4 3.2 Topography and geology 4 3.3 Relationship of the conservation area to its surroundings 5 3.4 Biodiversity 5 4 Historic development and archaeology 6 4.1 Historic development 6 4.2 Archaeology 13 5 Spatial analysis 14 5.1 Plan form, site layout and boundaries 14 5.2 Landmarks, focal points and views 14 5.3 Open spaces, trees and landscape 15 5.4 Public realm 16 6 The buildings of the conservation area 17 6.1 Building types 17 6.2 Listed buildings 17 6.3 Positive buildings 19 6.4 Building styles, materials and colours 19 7 Issues 21 7.1 Key positive characteristics 21 7.2 Key negative characteristics 21 7.3 Key issues 22 8 Recommendations 23 -

OART-Riverside-Walk-6.Pdf

Ouse & Adur Rivers Trust Riverside Walks Walk 6 – Lewes Brooks Circular Walk. (OS Map – Explorer 122) This is a 9 mile circular walk starting south of Lewes and taking in the villages of Iford, Northease, and Rodmell. On the walk you cross the Greenwich Meridian a total of 4 times, and enjoy some panoramic downland views from the valley of the Lower Ouse. Downland scenery Directions Start – TQ40450893, Park in the layby on the Kingston Road (C7), just south of Lewes Rugby Club. Looking Northwards, Lewes castle is visible on the horizon, and turning to look to the North East the 2 hills are Mount Caburn (on the left) and Firle Beacon (on the right). Follow the footpath signs down the track from the layby, through the gate, and take the right hand fork diagonally across the field to the gate in the hedge. In early July we saw plenty of butterflies including Gatekeepers, Commas, and Tortoiseshells. Pass through the gate and continue straight ahead through the middle of the field to the hedge. Waypoint 1 - TQ40390845, Looking to the left, the chalk cliffs mark the site of the Asham Cement Works which closed in 1978. Follow the narrow track under the trees keeping the barbed wire fence on your left. As you walk you pass a garden centre on your right. Continue over the stile, past the sewage treatment works on the left, at this point we spotted a number of alpacas in the field beyond. Whilst not typically Sussex animals, there are a number of farms keeping herds of alpacas for their fine fleece. -

A Reappraisal of the Date, Architectural Context and Significance of the Great Tower of Dudley Castle Hislop, Malcolm

University of Birmingham A missing link: a reappraisal of the date, architectural context and significance of the great tower of Dudley Castle Hislop, Malcolm DOI: 10.1017/S000358150999045X Citation for published version (Harvard): Hislop, M 2010, 'A missing link: a reappraisal of the date, architectural context and significance of the great tower of Dudley Castle', The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 90, pp. 211-233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000358150999045X Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Status Symbols: Royal and Lordly Residence

Royal and Lordly Residence in Scotland c.1050 to c.1250: an Historiographical Review and Critical Revision1 Richard D Oram Abstract Academic study of eleventh to thirteenth century high status residence in Scotland has been largely bypassed by the English debates over origin, function and symbolism. Archaeologists have also been slow to engage with three decades of historical revision of traditional socio- economic, cultural and political models upon which their interpretations of royal and lordly residence have drawn. Scottish castle-studies of the pre-1250 era continue to be framed by a ‘military architecture’ historiographical tradition and a view of the castle as an alien artefact imposed on the land by foreign adventurers and a ‘modernising’ monarchy and native Gaelic nobility. Knowledge and understanding of pre-twelfth century native high status sites is rudimentary and derived primarily from often inappropriate analogy with English examples. Discussion of native responses to the imported castle-building culture is founded upon retrospective projection of inappropriate later medieval social and economic models and anachronistic perceptions of military colonialism. Cultural and socio-economic difference is rarely recognised in archaeological modelling and cultural determinism has distorted perceptions of structural form, social status and material values. A programme of interdisciplinary studies focused on specific sites is necessary to provide a corrective to this current situation. One of the central themes in the traditional historiography of medieval Scotland is that in parallel with the emergence from the late 1000s of an identifiable noble stratum comparable to the aristocratic hierarchies of Norman England and Frankish Europe there was an attendant development of new forms in the physical expression of lordship.