Annual Report 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Access the List of Registered Aircraft As on 2Nd August

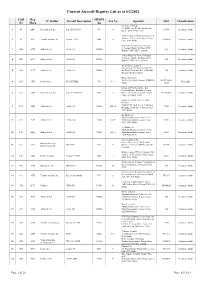

Current Aircraft Registry List as at 8/2/2021 CofR Reg MTOM TC Holder Aircraft Description Pax No Operator MSN Classification No Mark /kg Cherokee 160 Ltd. 24, Id-Dwejra, De La Cruz Avenue, 1 41 ABW Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-28-160 998 4 28-586 Aeroplane (land) Qormi QRM 2456, Malta Malta School of Flying Company Ltd. Aurora, 18, Triq Santa Marija, Luqa, 2 62 ACL Textron Aviation Inc. Cessna 172M 1043 4 17260955 Aeroplane (land) LQA 1643, Malta Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 3 1584 ACX Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 544 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 4 1583 ACY Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 582 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Air X Charter Limited SmartCity Malta, Building SCM 01, 5 1589 ACZ Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 4th Floor, Units 401 403, SCM 1001, 590 Aeroplane (land) Ricasoli, Kalkara, Malta Nazzareno Psaila 40, Triq Is-Sejjieh, Naxxar, NXR1930, 001-PFA262- 6 105 ADX Reno Psaila RP-KESTREL 703 1+1 Microlight Malta 12665 European Pilot Academy Ltd. Falcon Alliance Building, Security 7 107 AEB Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-34-200T 1999 6 Gate 1, Malta International Airport, 34-7870066 Aeroplane (land) Luqa LQA 4000, Malta Malta Air Travel Ltd. dba 'Malta MedAir' Camilleri Preziosi, Level 3, Valletta 8 134 AEO Airbus S.A.S. A320-214 75500 168+10 2768 Aeroplane (land) Building, South Street, Valletta VLT 1103, Malta Air Malta p.l.c. -

Structural Business Statistics: 2019

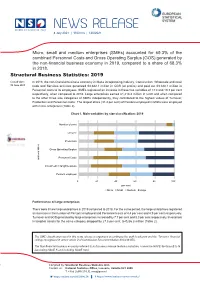

8 July 2021 | 1100 hrs | 120/2021 Micro, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) accounted for 69.3% of the combined Personnel Costs and Gross Operating Surplus (GOS) generated by the non-financial business economy in 2019, compared to a share of 68.3% in 2018. Structural Business Statistics: 2019 Cut-off date: In 2019, the non-financial business economy in Malta incorporating Industry, Construction, Wholesale and retail 30 June 2021 trade and Services activities generated €3,882.1 million in GOS (or profits) and paid out €3,328.1 million in Personnel costs to its employees. SMEs registered an increase in these two variables of 13.0 and 10.3 per cent respectively, when compared to 2018. Large enterprises earned €1,218.3 million in GOS and when compared to the other three size categories of SMEs independently, they contributed to the highest values of Turnover, Production and Personnel costs. The largest share (31.4 per cent) of Persons employed in Malta were employed with micro enterprises (Table 2). Chart 1. Main variables by size classification: 2019 Number of units Turnover Production Gross Operating Surplus Personnel Costs main variables Investment in tangible assets Persons employed 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% per cent Micro Small Medium Large Performance of large enterprises There were 8 new large enterprises in 2019 compared to 2018. For the same period, the large enterprises registered an increase in the number of Persons employed and Personnel costs of 4.4 per cent and 4.9 per cent respectively. Turnover and GOS generated by large enterprises increased by 7.7 per cent and 8.3 per cent respectively. -

A Demographic and Socio-Economie Profile of Ageing in Malta %Eno

A Demographic and Socio-Economie Profile of Ageing in Malta %eno CamiCCeri CICRED INIA Paris Valletta FRANCE MALTA A Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile of Ageing in Malta A Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile of Ageing in Malta %g.no CamiCCeri Reno Camilleri Ministry for Economic Services Auberge d'Aragon, Valletta Published by the International Institute on Ageing (United Nations - Malta) © INIAICICRED 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Reno Camilleri A Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile of Ageing in Malta ISBN 92-9103-024-4 Set by the International Institute on Ageing (United Nations — Malta) Design and Typesetting: Josanne Altard Printed in Malta by Union Print Co. Ltd., Valletta, MALTA Foreword The present series of country monographs on "the demographic and socio-economic aspects of population ageing" is the result of a long collaborative effort initiated in 1982 by the Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography (CICRED). The programme was generously supported by the United Nations Population Fund and various national institutions, in particular the "Université de Montréal", Canada and Duke University, U.S.A. Moreover, the realisation of this project has been facilitated through its co-sponsorship with the International Institute on Ageing (United Nations - Malta), popularly known as INIA/ There is no doubt that these country monographs will be useful to a large range of scholars and decision-makers in many places of the world. -

Malta Fisheries

PROJECT: FAO COPEMED ARTISANAL FISHERIES IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN Malta Fisheries The Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture of Malta By: Ignacio de Leiva, Charles Busuttil, Michael Darmanin, Matthew Camilleri. 1. Introduction The Maltese fishing industry may be categorised mainly in the artisanal sector since only a small number of fishing vessels, the larger ones, operate on the high seas. The number of registered gainfully employed full-time fishermen is 374 and the number of vessels owned by them is 302. Fish landings recorded at the official fish market in 1997 amounted to a total of 887 metric tonnes, with a value of approx. Lm 1.5 million (US$4,000,000). Fishing methods adopted in Malta are demersal trawling, "lampara" purse seining, deep-sea long-lining, inshore long-lining, trammel nets, drift nets and traps. The most important commercial species captured by the Maltese fleet are included as annex 1. 2. Fishing fleet The main difference between the full-time and artisanal category is that the smaller craft are mostly engaged in coastal or small scale fisheries. The boundary between industrial and artisanal fisheries is not always well defined and with the purpose of regional standardisation the General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean (GFCM), at its Twenty-first Session held in Alicante, Spain, from 22 to 26 May 1995, agreed to set a minimum length limit of 15 metres for the application of the "Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas" and therefore Maltese vessels over 15 m length should be considered as industrial in line with this agreement. -

American University of Malta Campus Marsascala Site

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT ___________________________________________________________________________ AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF MALTA CAMPUS MARSASCALA SITE Marvin Formosa PhD Joe Gerada MA, FCIPD ___________________________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project description 1.2 Social Impact Assessment 1.3 Methodology 2 SIA PHASE 1: THE MARSASCALA COMMUNITY 2.1 The historical context 2.2 The cultural context 2.3 Population and socio-economic structures 2.3.1 Population 2.3.2 Education 2.3.3 Employment 2.3.4 Risk-of-poverty 2.3.5 Health 3 SIA PHASE 2: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL IMPACT 3.1 Population impacts 3.2 Community/Institutional arrangements 3.3 Possible conflicts 3.4 Individual and family level impacts 3.5 Community infrastructure needs 3.6 Mitigation issues 4 CONCLUSION REFERENCES 0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ___________________________________________________________________________ Considerations of the social impacts of major projects would not be complete if the perceptions of the residents and stakeholders are overlooked. This Social Impact Assessment focuses on the possibility that the American University of Malta opens a campus in Marsascala. Residents and stakeholders in Marsascala were generally in favour to the possibility that a foreign university - the American University of Malta - establishes a campus in Zonqor. Positive attitudes were based on the perception that (i) this project is a prestigious project and therefore improves the image of the South and Marsascala in particular: -

Foreigners in Maltese Prisons: Spanning the 150-Year Divide

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 24 [Special Issue – December 2012] Foreigners in Maltese Prisons: Spanning the 150-year Divide Saviour Formosa, PhD Sandra Scicluna, PhD Janice Formosa Pace, MSc Department of Criminology Faculty for Social Wellbeing University of Malta Humanities A (Laws, Theology, Criminology) Msida MSD 2080 Abstract Reviewing the incidence of foreigners in the Maltese Islands’ prisons entails an understanding of the realities pertaining to each period under study. Taking a multi-methodological approach, this 150-year study initially qualitatively reviews the situational circumstances faced by Foreign and Maltese offenders between the mid 19th and mid 20th Century, followed by a quantitative and spatial analysis of the post 1950 period, followed by an indepth analysis of the 1990s offenders. A classification system of what is termed as a foreigner offender is created, which employment resulted in the findings that there are distinct differences in structure in terms of foreign offender and the offences they commit when compared to their Maltese counterparts. Findings show that the longer the foreigner stays on the islands, the higher the potentiality of emulation to the Maltese counterpart’s structure both in terms of offence type, offender residential and offence spatial locations. Keywords : Foreign offenders, spatial analysis, prisons, offender-offence relationship, Maltese Islands 1. Introduction The incidence of foreigners in Maltese prisons is virtually unknown with studies focusing on the generic ‘foreigner’ component, irrespective of the purpose of entry to Malta (Scicluna, 2004; Formosa, 2007). This paper investigates sentenced offenders in Malta’s prisons and develops a classification system which distinguishes between short-term visitors, long-term residents and foreigners who became Maltese citizens. -

LETTER CIRCULAR Date: 16Th December 2020 Ref: DLAP 281/2020 To: All Heads of College Network and Heads of Primary, Middle and Se

LETTER CIRCULAR Date: 16th December 2020 Ref: DLAP 281/2020 To: All Heads of College Network and Heads of Primary, Middle and Secondary Schools (State and Non- State) From: David Muscat – CEO, National Literacy Agency Subject: Book Champion Schools 2020 ________________________________________________________________________________________ The Literacy and Information Support Unit of the National Literacy Agency has organised the Book Champion Schools Awards as part of the World Book Day 2020 in collaboration with the Directorate for Learning and Assessment Programmes. Thirty six primary, middle and secondary schools received the Book Champion Schools Awards. These schools have demonstrated that they are actively promoting books, reading and literacy. Winners in each category: Gold, Silver and Bronze were awarded a certificate and a book voucher. Twenty five schools received the Gold Awards, two schools received the Bronze Award, and nine schools received the Silver Award as follows: Bronze Awards Laura Vicuna Primary School, Gozo St Nicholas College Dingli Secondary School Silver Awards Mariam Al-Batool School St Francis School, Victoria Gozo College Sannat Primary School Maria Reġina College Mosta Primary School B St Benedict College Żurrieq Primary School St Nicholas College Mġarr Primary School Immaculate Conception School, Tarxien St Joseph Senior School, Sliema St Ignatius College Ħandaq Middle School Gold Awards De La Salle College Junior School Sacred Heart College Junior School Gozo College Qala Primary School Gozo College Xewkija -

L-20 Ta' Jannar, 2021

L-20 ta’ Jannar, 2021 433 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sad-19 ta’ Frar, 2021. -

Local Government White Paper and Interrelated Regions and Districts

LOCAL GOVERNMENT WHITE PAPER AND INTERRELATED REGIONS AND DISTRICTS Perit Joseph Magro B.Sc.(Eng.)(Hons.), B.A.(Arch.) Update Note to the Addendum “Interrelated Regions and Districts for Malta and Gozo” Annexed to the Study Paper “Proposals For An Improved Malta Electoral System” This note proposes another solution of interrelated regions and districts, now based on the six regions as detailed in the Local Government White Paper. It also serves as a comparative study to the one put forward in the Addendum where a similar organizational structure of interrelated regions and districts for Malta and Gozo was proposed, with the districts also serving as electoral divisions. October 2018 LOCAL GOVERNMENT WHITE PAPER AND INTERRELATED REGIONS AND DISTRICTS Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 1.1 Reference to the Local Government White Paper 1.2 Reference to the Addendum 1.3 Main Objectives of This Update Note to the Addendum 1.4 Parameters Governing this Exercise 2. THE REGIONS AS ESTABLISHED IN THE WHITE PAPER ……………………………..…..………………………… 4 2.1 Maps of the Regions 3. ESTABLISHING THE DISTRICTS ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 3.1 Hamlets 3.2 Numbering of Regions and Districts 4. COMPARATIVE CASE STUDIES …………………………………………….……………..………………………………….. 6 4.1 Proposed Organizational Structure and Registered Voter Changes 4.2 District Seat Value 4.3 Registered Voter Changes between October 2007 and April 2018 5. CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Appendix 1: Map of the (White Paper) Regions and Proposed Districts …..…..….………………….……… 9 Appendix 2: Map of the Existing Regions of Malta ……………………………………………………………….…… 10 Appendix 3: Map of the Regions as Proposed in the White Paper ………………………………………….…. 11 2 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Reference to the Local Government White Paper The Local Government White Paper, published on 19th October 2018, refers to the existing five Regions of Malta as established by Act No. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 332 August 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 332 August 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 332 August 2020 Dar l-Emigrant, Castille Place, Valletta, 1062 Phone: (+356) 21222644, 21232545, 21240255 ; Web: www.mecmalta.com Għażiż Frank, Il-Kummissjoni Emigranti tingħaqad ma ħafna oħrajn li raddewlek ħajr għax-xogħol u s-servizz li wettaqt b’mod diliġenti u assidwu fil-kommunita’ Maltija l- aktar ta’ South Australia. Il-ħeġġa u l-imħabba għax-xogħol kienu valuri li jittieħdu minn oħrajn li jaħdmu miegħek. I-Entużjażmu li inti dejjem urejt fil-laqgħat tal-kumitatt tal-Maltin ta’ barra, kif ukoll waqt il-Konvenzjonijiet li kellna ħalla l-frott tiegħu. M’għandniex xi ngħidu għall-kontribut li inti tajt biex tibqa toħroġ l- Newsletter eletronika. Dan hu kollu xogħol li jibqa’ u jħalli l-marka tiegħu fl-istorja. Aħna nħossuna grati li permezz tax-xogħol tiegħek u ta’ sħabek l-istorja inkitbet biex tibqa’ memorja ta’ dejjem li tagħmel ġiegħ lill-Maltin li ħallew art twelidhom, fi żminijiet diffiċli biex joffru futur sabiħ għalihom u l-familja tagħhom. Mhux biss, imma għamlu isem għal Malta kull fejn marru. Nitolbu biex il-ġenerazzjonijiet futuri japprezzaw dan ix- xogħol u is-sagriffiċji kollha u jibqgħu ikunu xhieda u denji tal-għeruq Maltin tagħhom. Nixtiequlek kull saħħa, ġid u barka. Mons. Fr. Alfred Vella Director THE CELEBRATION OF MARIA BAMBINA AT ST MARY’S CATHEDRAL SYDNEY CANCELLED During the COVID-19 Pandemic restrictions, due to the safety of our community, we have to ensure the well being of those who every year attend the celebration of Maria Bambina or il- Vitorja at St Mary’s Cathedral Sydney. -

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr. Carl Rasmussen MAY 11-22, 2021 organized by Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome / May 11-22, 2021 Malta Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MAY 11-22, 2021 Fri 14 May Ferry to POZZALLO (SICILY) - SYRACUSE – Ferry to REGGIO CALABRIA Early check out, pick up our box breakfasts, meet the English-speaking assistant at our hotel and transfer to the port of Malta. 06:30am Take a ferry VR-100 from Malta to Pozzallo (Sicily) 08:15am Drive to Syracuse (where Paul stayed for three days, Acts 28.12). Meet our guide and visit the archeological park of Syracuse. Drive to Messina (approx. 165km) and take the ferry to Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland (= Rhegium; Acts 28:13, where Paul stopped). Meet our guide and visit the Museum of Magna Grecia. Check-in to our hotel in Reggio Calabria. Dr. Carl and Mary Rasmussen Dinner at our hotel and overnight. Greetings! Mary and I are excited to invite you to join our handcrafted adult “study” trip entitled Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Sat 15 May PAESTUM - to POMPEII Martyrdom in Rome. We begin our tour on Malta where we will explore the Breakfast and checkout. Drive to Paestum (435km). Visit the archeological bays where the shipwreck of Paul may have occurred as well as the Island of area and the museum of Paestum. Paestum was a major ancient Greek city Malta. Mark Gatt, who discovered an anchor that may have been jettisoned on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). -

Proposals for an Improved Maltese Electoral System

Study Paper PROPOSALS FOR AN IMPROVED MALTA ELECTORAL SYSTEM Perit Joseph Magro B.Sc.(Eng.) (Hons.), B.A.(Arch.) A Study Paper that analysis the results of all the twenty four General Elections held in Malta between 1921 and 2017 and proposes revisions to the current Single Transferable Vote System: - to make the electoral system fairer for all contesting candidates and political parties - to make the final result of the General Elections truly reflect the choices of the electorate April 2018 PROPOSALS FOR AN IMPROVED MALTA ELECTORAL SYSTEM Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Definitions of Terms used in the Document .................................................................................... 5 1.2 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 6 2. REGULATION OF THE REGISTERED VOTERS AND GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS ................................. 7 3. THE QUOTA IN EACH ELECTORAL DIVISION ....................................................................................... 10 3.1 The Current System ................................................................................................................... 10 3.2 The Proposed System ...............................................................................................................