Lunarchy – Rule by the Moon Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flagstaff Men's Fashion Unless the New Car You Lust After Is a BMW 7-Series

THE Page 2 Steady as a rock for No Doubt Alu mjn »<jjh just could not wait Etcetera Writer Jl s rj | any longer to release their most However soon the ska boom hit and abandoned popular experimental album radio, No Doubt, and especially Gwen Stefani, we're not so crazy yet. easily forgotten. Stefani, recognized for her pink hair and 'cause that's Rolling Stone eccentric fashion sense, guided No Doubt to the top of the all our influ Magazine says charts with songs like "Don't Speak" and ")ust a GirJ" in ences. I about the album: 1996. Gwen also guided the likes of songwriter Moby and mean, we "The music on Rock rapper Eve to the top of the charts with the help of her dis grew up lis Steady is simple tinguishable vocals on "South Side" and "Let Me Blow Va tening to and propulsive, Mind.1' No Doubt has released their fifth album, Rock English ska which... forces the Steady, which proves to be a collection of eclectic, danceable and then reg songs to improve." tunes. - . gae and all And the songs defi Return of Saturn, released in 2(X)0, was an effort in which that stuff. nitely improve, with No Doubt wanted to prove that they were a band of talent And then the strong efforts of ed, maturi1 musicians. "A Simple Kind of Life," Gwen's we're from the entire band— attempt to deal with the crisis of turning 30, was, no doubt, Orange both the well a masterpiece written by Stefani. -

U Rises E in 0 Igm in HVAC Accident

0 ELTON JOHN ,R R" See the Grammy winning artist' cartoon likeness singing e song from '' nep the movie "The Roed to El .l, Dorado.'ARTSpage9 ' W THE S 7 U 0 E N T I K VO C E S I N C E 1 8 9 8 ';. 1 Bora.b Symposium UI worker dies u rises e in 0 igm in HVAC accident ax."j': ~ ri By Ruth Snow the accident occurred. The building By Jodie Salz Argonaut Editor in Chief was recently remodeled, and con- Argonaut Senior Writer tains state of the art safety features and signage Joel Crisp, a heating-ventilation- This type of accident has never air conditioning occurred at Ul before, and it is the 5,; This year's Borah Symposium theme (HVAC) technician M'"-.''-,-'.",5 was at Ul, was killed in an industrial only fatality of a Ul employee "on "Natural Resource Conflict in the 21st accident on Thursday. the job" in recent memory, according Century". Its purpose is to enlighten UI stu- Crisp, a Ul to Kathy Barnard, a university dents and the community about conflicts, cur- employee for the past year, responded to a spokesperson. rent and future, surrounding the use of Earth' service call in the mechanical room of the Gauss- "The entire University of Idaho natural resources including soil, water, air, Johnson Engineering Building community shares the grief of Joel's plants and animals. Although most of the pre- late Thursday afternoon. family and friends," said UI sentations went smoothly as planned, others Crisps'ody was found President Bob Hoover in a prepared contained surprising candor, such as Ted when his wife contacted officials at the univer- statement. -

Eros and the Shattering Gaze

PSYCHOLOGY / MOVEMENTS / JUNGIAN This is the book for those who fear that Jungian efforts to gaze deeply into the Self are simply carrying coals to the Newcastle of Narcissistic Personality Disorder. Its author, Ken Kimmel, certainly shows us the egoistic pitfalls that can attend such an enterprise, but he also makes us see why he believes that in- ner work really does hold the power to shake the foundations of someone’s inability to see the face of the Other. One comes away from reading Eros and the Shattering Gaze with renewed understanding as to why brave patients have subjected themselves to this very deep form of scrutiny and why fine therapists like Kimmel have been willing to see them through it. Attempting the rescue of authentic eros from its fear-driven shadow of predation is a work that will engage most of us at some point in our relational lives. We should be grateful for the insights with which this book is studded, for they can enlighten the labors of learning to love. —John Beebe, Jungian analyst, author of Integrity in Depth A skilful and articulate interweave of the best of traditional views on ‘relationality’ and more contempo- rary critique. The vivid clinical vignettes bring the arguments alive and the result is a stimulating and fresh take on this ever-timely topic. The sections on the ‘split feminine’ in contemporary men are especially fine, EROS AND THE SHATTERING GAZE eschewing sentimentality without abandoning hope. —Professor Andrew Samuels, Centre for Psychoanalytic Studies, University of Essex. The author is an extremely sensitive and experienced specialist who possesses a broad perspective and profound historical psychological knowledge. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

The Echo: April 14, 2000

. Taylor University Student News t&i4 See page 8 April!4,2000HCHO Volume 87, Issue 21 Almost a 'grand' old time 'Thousandaire' winner Neier walks away with Fennig and change Hair today... pg. 3 HILLARY BOSS SAC member and game show Olsen women donate Staff Writer' night produce,r Vinnie hair for childrens' charity. Last night, SAC gave Taylor Manganello, selected fifteen students a chance to win one men from the audience to have a thousand dollars. chance to win a date with Neier. SAC sponsored its own version They began the game with a pie of "Who wants to be a million eating contest, in which the first aire?" Freshman Ashlee Neier ten men to eat a slice of pie won the most money, even advanced to the next round. A challange pg. 4 though it was only 108 dollars Those ten contestants raced in John Molineux chal- out of a possible thousand. pairs on a Nintendo Power Pad langes spiritual growth Neier was one of the first ten to determine five semi-finalists. on campus. contestants to be randomly Neier asked the final five bach selected from the audience. The elors two questions each and Letter to editor pg. 5 ten contestants answered • a then she selected three finalists. Anonymous "voice of "fastest finger" question. The The three men were given a reason" berates "bubble" winner of that round moved on to list for a scavenger hunt within colurhn. the "hot seat." Rediger Auditorium. The first Once in the "hot seat" the con one to return to the stage with testant answered multiple choice twenty hymnals, an engagement questions that were projected on ring, a Taylor athlete and a few a screen. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

No Doubt Return of Saturn Mp3, Flac, Wma

No Doubt Return Of Saturn mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Return Of Saturn Country: Ukraine Released: 2002 Style: Alternative Rock, Ska MP3 version RAR size: 1587 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1139 mb WMA version RAR size: 1559 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 346 Other Formats: MP3 WAV MOD AAC MP4 DTS ASF Tracklist Hide Credits Ex-Girlfriend 1 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont*, T. Kanal* Bathwater 2 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont*, T. Kanal* Simple Kind Of Life 3 Written-By – G. Stefani* Six Feet Under 4 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Kanal* Magic's In The Makeup 5 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont* Artificial Sweetner 6 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont*, T. Kanal* Marry Me 7 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Kanal* New 8 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont* Too Late 9 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont*, T. Kanal* Big Distraction 10 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont* Suspension Without Suspense 11 Written-By – G. Stefani* Staring Problem 12 Written-By – E. Stefani*, G. Stefani*, T. Dumont*, T. Kanal* Home Now 13 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Kanal* Dark Blue 14 Written-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont* Credits Mixed By – Jack Joseph Puig Producer – Glen Ballard (tracks: 1-7, 9, 11-14), Jerry Harrison (tracks: 8), Matthew Wilder (tracks: 10), No Doubt (tracks: 8, 10) Recorded By – Alain Johannes, Karl Derfler Notes Promotional copy. Not for resale. Barcode and Other Identifiers Label Code: LC 06406 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Return Of Saturn (CD, Interscope Records, UK & -

United States District Court for the Middle District of Georgia Macon Division

Case 5:06-cv-00230-HL Document 8 Filed 02/12/07 Page 1 of 3 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA MACON DIVISION WARNER BROS. RECORDS INC., a ) Delaware corporation; INTERSCOPE ) RECORDS, a California general partnership; ) UMG RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware ) corporation; ARISTA RECORDS LLC, a ) Delaware limited liability company; BMG ) MUSIC, a New York general partnership; and ) SONY BMG MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, a ) Delaware general partnership, CIVIL ACTION FILE ) ) Plaintiffs, No. 5:06-cv-00230-DF ) ) v. ) ) GLORIA JACKSON, ) ) Defendant. ) DEFAULT JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Motion for Default Judgment, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Plaintiffs seek the minimum statutory damages of $750 per infringed work, as authorized under the Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. § 504(c)(1)), for each of the fifteen sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint. Accordingly, having been adjudged to be in default, Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Twelve Thousand Dollars ($12,000.00). 2. Defendant shall further pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Four Hundred Twenty Dollars ($420.00). Case 5:06-cv-00230-HL Document 8 Filed 02/12/07 Page 2 of 3 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights under federal or state law in the following copyrighted -

First Amended Complaint for Federal Copyright

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 45 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ARISTA RECORDS LLC; ATLANTIC RECORDING CORPORATION; BMG MUSIC; CAPITOL RECORDS, INC.; ELEKTRA ENTERTAINMENT GROUP INC.; INTERSCOPE RECORDS; LAFACE RECORDS LLC; ECF CASE MOTOWN RECORD COMPANY, L.P.; PRIORITY RECORDS LLC; SONY BMG MUSIC FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR ENTERTAINMENT; UMG RECORDINGS, INC.; FEDERAL COPYRIGHT VIRGIN RECORDS AMERICA, INC.; and INFRINGEMENT, COMMON LAW WARNER BROS. RECORDS INC., COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT, Plaintiffs, UNFAIR COMPETITION, CONVEYANCE MADE WITH v. INTENT TO DEFRAUD AND UNJUST ENRICHMENT LIME WIRE LLC; LIME GROUP LLC; MARK GORTON; GREG BILDSON, and M.J.G. LIME 06 Civ. 05936 (GEL) WIRE FAMILY LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, Defendants. Plaintiffs hereby allege on personal knowledge as to allegations concerning themselves, and on information and belief as to all other allegations, as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiffs are record companies that produce, manufacture, distribute, sell, and license the vast majority of commercial sound recordings in this country. Defendants' business, operated under the trade name "LimeWire" and variations thereof, is devoted essentially to the Internet piracy of Plaintiffs' sound recordings. Defendants designed, promote, distribute, support and maintain the LimeWire software, system/network, and related services to consumers for the well-known and overarching purpose of making and distributing unlimited copies of Plaintiffs' sound recordings REDACTED VERSION - COMPLETE VERSION FILED UNDER SEAL Dockets.Justia.com without paying Plaintiffs anything. Plaintiffs bring this action to stop Defendants' massive and daily infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights. 2. The scope of infringement caused by Defendants is staggering. Millions of infringing copies of Plaintiff s sound recordings have been made and distributed through LimeWire — copies that can be and are permanently stored, played, and further distributed by Lime Wire's users. -

No Doubt Hey Baby Mp3, Flac, Wma

No Doubt Hey Baby mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Hey Baby Country: Australasia Released: 2001 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1357 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1514 mb WMA version RAR size: 1911 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 310 Other Formats: DTS MP1 FLAC AAC APE MMF ADX Tracklist Hide Credits Hey Baby Engineer [Additional Engineering] – Count, Rory Baker, Tkae MendezExecutive- Producer – Brian*, Wayne JobsonFeaturing – Bounty KillerMixed By, Producer 1 [Additional Production] – Mark "Spike" Stent*Producer [Additional Production], 3:26 Programmed By – Philip SteirProducer [Produced By] – No Doubt, Sly & RobbieProgrammed By [Programming] – Sly Dunbar, Tom Dumont, Tony KanalRecorded By – Dan ChaseWritten-By – G. Stefani*, R. Price*, T. Dumont*, T. Kanal* Hey Baby (The Homeboy Mix) 2 3:46 Remix – F.A.B.Z. Ex-Girlfriend (The Psycho Ex Mix) Keyboards – Gabrial McNairProducer [Produced By] – Glen BallardRecorded By – Karl 3 5:08 DerflerRemix, Producer [Additional Production] – Philip SteirWritten-By – G. Stefani*, T. Dumont*, T. Kanal* Hey Baby Video Video Film Director [Directed By] – Dave Meyers Companies, etc. Marketed By – Universal Music Australia Phonographic Copyright (p) – Interscope Records Copyright (c) – Interscope Records Made By – SSD Published By – World Of The Dolphin Music Published By – Universal Music Corp. Credits Bass Guitar, Keyboards – Tony Kanal Drums – Adrian Young Guitar, Keyboards – Tom Dumont Vocals – Gwen Stefani Notes Hey Baby taken from the album Rock Steady ℗© 2001 Interscope Records. Marketed in Australasia by Universal Music Australia under exclusive license. Made in Australia. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0606949766429 Barcode (text): 0 606949 766429 Matrix / Runout (Variants 1 & 2): * 4976642 * #01 MADE by SSD. -

Download Surviving Saturn's Return : Overcoming the Most Tumultuous

Surviving Saturn's Return : Overcoming the Most Tumultuous Time of Your Life: Overcoming the Most Tumultuous Time of Your Life, Sherene Schostak, Weiss Stefanie, McGraw Hill Professional, 2003, 0071421963, 9780071421966, 288 pages. For the first time, psychological strategies for surviving the astrological fallout of turning the big 3-0! Many young women approach their 30th birthdays with anxiety. They suddenly notice every tiny wrinkle, question the speed of their corporate ladder climb, or suffer from a biological clock that rivals Big Ben. Is it vanity, fear of aging, early midlife crisis, or insanity? It's actually the result of what astrologers call the "Saturn Return," a phenomenon occurring every 28 years, when Saturn completes its cycle through an individual's birth chart. At this crucial juncture, women often experience a crisis of self, unexplained chaotic feelings, or the uncertainty of personal and professional crossroads. In Surviving Saturn's Return, the first book to explore the subject, the authors combine their psychological and astrological expertise to demystify this cosmic source of strife and offer self-help strategies for surviving, even thriving, during this "quarterlife" crisis. In a fun, friendly, and reassuring tone, they explain how to deal with everything from the father complex to money to marriage to maturing confidently into adulthood.. DOWNLOAD HERE Saturn Cycles Mapping Changes in Your Life, Wendell C. Perry, Jan 1, 2009, Body, Mind & Spirit, 308 pages. Saturn has an immense developmental impact on our lives at every major stage, from childhood to adulthood. This book introduces you to the technique of mapping Saturn transits .... Retrograde Planets Traversing the Inner Landscape, Erin Sullivan, Jan 1, 2002, , 446 pages. -

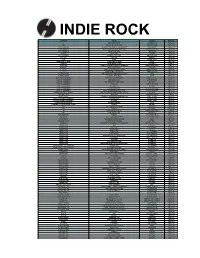

Order Form Full

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I.