Biting the Bullet: International Action on Small Arms 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

501 Cmr: Executive Office of Public Safety

501 CMR: EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF PUBLIC SAFETY 501 CMR 7.00: APPROVED WEAPON ROSTERS Section 7.01: Purpose 7.02: Definitions 7.03: Development of Approved Firearms Roster 7.04: Criteria for Placement on Approved Firearms Roster 7.05: Compliance with the Approved Roster by Licensees 7.06: Appeals for Inclusion on or Removal from the Approved Firearms Roster 7.07: Form and Publication of the Approved Firearms Roster 7.08: Development of a Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.09: Criteria for Placement on Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.10: Large Capacity Weapons Not Listed 7.11: Form and Publication of the Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.12: Development of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.13: Criteria for Placement on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.14: Appeals for Inclusion on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.15: Form and Publication of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.16: Severability 7.01: Purpose The purpose of 501 CMR 7.00 is to provide rules and regulations governing the inclusion of firearms, rifles and shotguns on rosters of weapons referred to in M.G.L. c. 140, §§ 123 and 131¾. 7.02: Definitions As used in 501 CMR 7.00: Approved Firearm means a firearm make and model that passed the testing requirements of M.G.L. c. 140, § 123 and was subsequently approved by the Secretary. Included are those firearms listed on the current Approved Firearms Roster and those firearms approved by the Secretary of Public Safety that will be included on the next published Approved Firearms Roster. -

California State Laws

State Laws and Published Ordinances - California Current through all 372 Chapters of the 2020 Regular Session. Attorney General's Office Los Angeles Field Division California Department of Justice 550 North Brand Blvd, Suite 800 Attention: Public Inquiry Unit Glendale, CA 91203 Post Office Box 944255 Voice: (818) 265-2500 Sacramento, CA 94244-2550 https://www.atf.gov/los-angeles- Voice: (916) 210-6276 field-division https://oag.ca.gov/ San Francisco Field Division 5601 Arnold Road, Suite 400 Dublin, CA 94568 Voice: (925) 557-2800 https://www.atf.gov/san-francisco- field-division Table of Contents California Penal Code Part 1 – Of Crimes and Punishments Title 15 – Miscellaneous Crimes Chapter 1 – Schools Section 626.9. Possession of firearm in school zone or on grounds of public or private university or college; Exceptions. Section 626.91. Possession of ammunition on school grounds. Section 626.92. Application of Section 626.9. Part 6 – Control of Deadly Weapons Title 1 – Preliminary Provisions Division 2 – Definitions Section 16100. ".50 BMG cartridge". Section 16110. ".50 BMG rifle". Section 16150. "Ammunition". [Effective until July 1, 2020; Repealed effective July 1, 2020] Section 16150. “Ammunition”. [Operative July 1, 2020] Section 16151. “Ammunition vendor”. Section 16170. "Antique firearm". Section 16180. "Antique rifle". Section 16190. "Application to purchase". Section 16200. "Assault weapon". Section 16300. "Bona fide evidence of identity"; "Bona fide evidence of majority and identity'. Section 16330. "Cane gun". Section 16350. "Capacity to accept more than 10 rounds". Section 16400. “Clear evidence of the person’s identity and age” Section 16410. “Consultant-evaluator” Section 16430. "Deadly weapon". Section 16440. -

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” Quick Reference Guide

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” quick Reference Guide PREREQUISITE FEATURES or telescoping stock, (D) A grenade launcher or the weapon without burning the bearer’s hand, QUICK TIPS OF AN ASSAULT WEAPON (AW) flare launcher, (E) A flash suppressor, or (F) A except a slide that encloses the barrel; (J) The FOR GUN OWNERS WITH The Penal Code now classifies the following as forward pistol grip. capacity to accept a detachable magazine at FIREARMS NOW an AW: PISTOLS: A semiautomatic pistol that does not some location outside of the pistol grip. have a fixed magazine but has anyone of the SHOTGUNS: While the change in the Penal CLASSIFIED AS RIFLES: A semiautomatic, centerfire rifle that following: (G) A threaded barrel, capable of ac- Code affects certain rifles and pistols, the DOJ does not have a fixed magazine but has any “ASSAULT WEAPONS” cepting a flash suppressor, forward handgrip, has taken the position that semiautomatic shot- one of the following: (A) A pistol grip that pro- or silencer; (H) A second handgrip; (I) A shroud guns required to be equipped with “bullet but- On January 1, 2017, the definition trudes conspicuously beneath the action of the that is attached to, or partially or completely en- tons” are also affected. of an “assault weapon” (“AW”) under weapon, (B) A thumbhole stock, (C) A folding California law was changed to include circles, the barrel that allows the bearer to fire firearms which were required to be equipped with a “bullet button” or similar KEY DEFINITIONS magazine locking device. This change does not affect ex- “FIXED MAGAZINE”- An ammunition feeding device contained in, or permanently attached to, a firearm in such a manner that the device cannot isting definitions of other types of AWs, be removed without disassembly of the firearm action. -

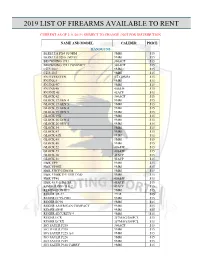

2019 List of Firearms Available to Rent

2019 LIST OF FIREARMS AVAILABLE TO RENT CURRENT AS OF 2/11/2019 | SUBJECT TO CHANGE | NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS BERETTA PX4 STORM 9MM $15 BERETTA 92FS | M9A1 9MM $15 BROWNING 1911 380ACP $15 BROWNING 1911 COMPACT 380ACP $15 CZ P-10 C 9MM $15 CZ P-10 F 9MM $15 FN FIVESEVEN 5.7X28MM $15 FN FNS-9 9MM $15 FN FNS-9C 9MM $15 FN FNS-40 40S&W $15 FN FNX-45 45ACP $15 GLOCK 42 380ACP $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19X 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 34 9MM $15 GLOCK 43 9MM $15 GLOCK 43X 9MM $15 GLOCK 45 9MM $15 GLOCK 48 9MM $15 GLOCK 22 40S&W $15 GLOCK 23 40S&W $15 GLOCK 36 45ACP $15 GLOCK 21 45ACP $15 H&K VP9 9MM $15 H&K VP9SK 9MM $15 H&K P30 V-3 DA/SA 9MM $15 H&K P30SK V-1 LEM DAO 9MM $15 H&K VP40 40S&W $15 H&K 45 V-1 DA/SA 45ACP $15 KIMBER PRO TLE 2 45ACP $15 REMINGTON RP9 9MM $15 RUGER SR-22 22LR $15 RUGER LC9S-PRO 9MM $15 RUGER EC9S 9MM $15 RUGER AMERICAN COMPACT 9MM $15 RUGER SR9E 9MM $15 RUGER SECURITY-9 9MM $15 RUGER LCR 357MAG/38SPCL $15 RUGER LCRX 357MAG/38SPCL $15 SIG SAUER P238 380ACP $15 SIG SUAER P938 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P225 A-1 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P226 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P229 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P320 CARRY 9MM $15 NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS SIG SAUER P320–M17 9MM 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P365 9MM $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P22 COMPACT 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON REVOLVER 617 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON BODYGUARD 380 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P380 SHIELD EZ 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P9 M2.0 5” FDE 9MM $15 SMITH & -

Information Bulletin 2014-BOF-01 New and Amended Firearms/Weapons Laws Page 2

Kamala D. Harris, Attorney General California Department of Justice DIVISION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT Larry J. Wallace, Director Subject: No: 2014-BOF-01 New and Amended Firearms/Weapons Laws Date: Bureau of Firearms January 10,2014 TO: All California Criminal Justice and Law Enforcement Agencies, Centralized List of Firearms Dealers, Manufacturers, and Exempted Federal Firearms Licensees This bulletin provides a brief summary of new and amended California firearms/weapons laws that take effect January 1, 2014, unless otherwise noted. You may access the full text of the bills via the Internet at http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/. AB 809 (Stats. 2011, ch. 745)- Collection and Retention of Long Gun Information • Commencing January 1, 2014, requires information regarding the sale or transfer oflong guns (rifles and shotguns) to be reported, collected, and retained in the same manner as handguns. (Pen. Code,§§ 11106, 26905.) AB 1559 (Stats. 2012, ch. 691) -Fees • Commencing January 1, 2014, only one processing fee will be charged for a single transaction (e.g. sale, transfer, miscellaneous reports of ownership, etc.) regardless ofthe number offirearms. (Pen. Code,§ 28240.) AB 48 (Stats. 2013, ch. 728)- Large-Capacity Magazines • With specified exceptions, makes it a misdemeanor to knowingly manufacture, import, keep for sale, offer or expose for sale, or give, lend, buy, or receive any large-capacity magazine conversion kit that is capable of converting an ammunition feeding device into a large-capacity magazine. (Pen. Code, § 32311.) • With specified exceptions, makes it either a misdemeanor or a felony to buy or receive a large capacity magazine. (Pen. Code, § 3231 0.) AB 170 (Stats. -

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law

Guide on Firearms Licensing Law April 2016 Contents 1. An overview – frequently asked questions on firearms licensing .......................................... 3 2. Definition and classification of firearms and ammunition ...................................................... 6 3. Prohibited weapons and ammunition .................................................................................. 17 4. Expanding ammunition ........................................................................................................ 27 5. Restrictions on the possession, handling and distribution of firearms and ammunition .... 29 6. Exemptions from the requirement to hold a certificate ....................................................... 36 7. Young persons ..................................................................................................................... 47 8. Antique firearms ................................................................................................................... 53 9. Historic handguns ................................................................................................................ 56 10. Firearm certificate procedure ............................................................................................... 69 11. Shotgun certificate procedure ............................................................................................. 84 12. Assessing suitability ............................................................................................................ -

Canada Gazette, Part II

EXTRA Vol. 154, No. 3 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 154, no 3 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part II Partie II OTTAWA, FRIDAY, MAY 1, 2020 OTTAWA, LE VENDREDI 1er MAI 2020 Registration Enregistrement SOR/2020-96 May 1, 2020 DORS/2020-96 Le 1er mai 2020 CRIMINAL CODE CODE CRIMINEL P.C. 2020-298 May 1, 2020 C.P. 2020-298 Le 1er mai 2020 Whereas the Governor in Council is not of the opinion Attendu que la gouverneure en conseil n’est pas d’avis that any thing prescribed to be a prohibited firearm or que toute chose désignée comme arme à feu prohibée a prohibited device, in the Annexed Regulations, is ou dispositif prohibé dans le règlement ci-après peut reasonable for use in Canada for hunting or sporting raisonnablement être utilisée au Canada pour la purposes; chasse ou le sport, Therefore, Her Excellency the Governor General in À ces causes, sur recommandation du ministre de la Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of Justice et en vertu des définitions de « arme à feu à Justice, pursuant to the definitions “non-restricted autorisation restreinte »1a, « arme à feu prohibée »a, firearm”1a, “prohibited device”2b, “prohibited firearm”b « arme à feu sans restriction »2b et « dispositif prohi- and “restricted firearm”b in subsection 84(1) of the bé »a au paragraphe 84(1) du Code criminel 3c et du Criminal Code 3c and to subsection 117.15(1)b of that paragraphe 117.15(1)a de cette loi, Son Excellence la Act, makes the annexed Regulations Amending the Gouverneure générale en conseil prend le Règlement Regulations Prescribing Certain Firearms and Other modifiant le Règlement désignant des armes à feu, Weapons, Components and Parts of Weapons, Acces- armes, éléments ou pièces d’armes, accessoires, char- sories, Cartridge Magazines, Ammunition and Project- geurs, munitions et projectiles comme étant prohibés, iles as Prohibited, Restricted or Non-Restricted. -

Order Granting Defendants' Motion for Summary

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND * STEPHEN V. KOLBE, et al. * * * v. * Civil No. CCB-13-2841 * * MARTIN J. O’MALLEY, et al. * * ****** MEMORANDUM On May 16, 2013, in the wake of a number of mass shootings, the most recent of which claimed the lives of twenty children and six adult staff members at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, the Governor of Maryland signed into law the Firearm Safety Act of 2013. The Act bans certain assault weapons and large-capacity magazines (“LCMs”). Plaintiffs Stephen V. Kolbe, Andrew C. Turner, Wink’s Sporting Goods, Inc., Atlantic Guns, Inc., Associated Gun Clubs of Baltimore, Inc. (“AGC”), Maryland Shall Issue, Inc., Maryland State Rifle and Pistol Association, Inc., National Shooting Sports Foundation, Inc. (“NSSF”), and Maryland Licensed Firearms Dealers Association, Inc. (“MLFDA”)1 brought this action against defendants Martin J. O’Malley, Douglas F. Gansler, Marcus L. Brown, and Maryland State Police (“MSP”),2 requesting a judgment declaring Maryland’s gun control legislation unconstitutional.3 Now pending before the court are the defendants’ motion for 1 The plaintiffs are various associations of gun owners and advocates, companies in the business of selling firearms and magazines, and individual gun-owning citizens of Maryland. 2 All the defendants are sued in their official capacities. 3 The defendants do not challenge the plaintiffs’ standing to bring this lawsuit. Exercising its independent duty to ensure that jurisdiction is proper, the court is satisfied that individual plaintiffs Kolbe and Turner face a credible threat of prosecution under the Firearm Safety Act. -

US Firearms Trafficking to Mexico

U.S. Firearms Trafficking to Mexico: New Data and Insights Illuminate Key Trends and Challenges Colby Goodman Michel Marizco Working Paper Series on U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation September 2010 1 Brief Project Description This Working Paper is the product of a joint project on U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation coordinated by the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Trans-Border Institute at the University of San Diego. As part of the project, several leading experts have been invited to prepare research papers that provide background on organized crime in Mexico, the United States, and Central America, and analyze specific challenges for cooperation between the United States and Mexico, including efforts to address the consumption of narcotics, money laundering, arms trafficking, intelligence sharing, police strengthening, judicial reform, and the protection of journalists. This working paper is being released in a preliminary form to inform the public about key issues in the public and policy debate about the best way to confront drug trafficking and organized crime. Together the working paper series will form the basis of a forthcoming edited volume. All papers, along with other background information and analysis, can be accessed online at The Mexico Institute and the Trans-Border Institute and are copyrighted to the author. The project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation. The views of the author do not represent an official position of the Woodrow Wilson Center or the University of San Diego. For questions related to the project, for media inquiries, or if you would like to contact the author please contact the project coordinator, Eric L. -

Written Testimony of Mark W. Pennak, President, Msi, in Opposition to Hb 612

nt . Pennak February 25, 2019 WRITTEN TESTIMONY OF MARK W. PENNAK, PRESIDENT, MSI, IN OPPOSITION TO HB 612 I am the President of Maryland Shall Issue (“MSI”). Maryland Shall Issue is an all- volunteer, non-partisan organization dedicated to the preservation and advancement of gun owners’ rights in Maryland. It seeks to educate the community about the right of self- protection, the safe handling of firearms, and the responsibility that goes with carrying a firearm in public. I am also an attorney and an active member of the Bar of the District of Columbia. I recently retired from the United States Department of Justice, where I practiced law for 33 years in the Courts of Appeals of the United States and in the Supreme Court of the United States. I am an expert in Maryland Firearms Law, federal firearms law and the law of self-defense. I am also a Maryland State Police certified handgun instructor for the Maryland Wear and Carry Permit and the Maryland Handgun Qualification License (“HQL”) and a certified NRA instructor in rifle, pistol and personal protection in the home and outside the home as well as a range safety officer. I appear in opposition to HB 612. Current law, the Statutory Scheme and HBARs: Under current law, MD Code, Public Safety, § 5-101(r)(2) contains a long list of firearms which the statute defines as a “regulated firearm” That list includes, at Section 5- 101(r)(2)(xv) a “Colt AR–15, CAR–15, and all imitations except Colt AR–15 Sporter H–BAR rifle.” (Emphasis added). -

Magistrate No. 07–M–2048 (JS) SHAIN DUKA

44444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444U United States District Court District of New Jersey 44444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444U UNITED STATES OF AMERICA : : CRIMINAL COMPLAINT v. : : Magistrate No. 07–M–2048 (JS) SHAIN DUKA : I, the undersigned complainant, being duly sworn, state the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. From on or about January 3, 2006 to on or about May 7, 2007, in Camden, Burlington, and Monmouth Counties, in the District of New Jersey, and elsewhere, defendant SHAIN DUKA, committed the following offenses: SEE ATTACHMENT A. I further state that I am a Special Agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and that this complaint is based on the following facts: SEE ATTACHMENT B. Attachment A and Attachment B are incorporated as if set forth in full herein. Signature of Complainant John J. Ryan, Special Agent Federal Bureau of Investigation Sworn to before me and subscribed in my presence, May 7, 2007 at Date Camden, New Jersey Honorable Joel Schneider United States Magistrate Judge Name & Title of Judicial Officer Signature of Judicial Officer ATTACHMENT A COUNT 1 From on or about January 3 2006 to on or about May 7, 2007, in Camden, Burlington, and Monmouth Counties, in the District of New Jersey, and elsewhere, defendant SHAIN DUKA, did knowingly and willfully conspire and agree with Mohmad Ibrahim Shnewer, Dritan Duka, a/k/a “Distan Duka,” a/k/a “Anthony Duka,” a/k/a “Tony Duka,” Eljvir Duka, a/k/a “Elvis Duka,” a/k/a “Sulayman,” and Serdar Tatar, to kill officers and employees of agencies in the Executive Branch of the United States Government, namely, members of the uniformed services, while such officers and employees were engaged in and on account of the performance of official duties, and persons assisting such officers and employees in the performance of such duties and on account of that assistance, contrary to Title 18, United States Code, Section 1114. -

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Legislative

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA LEGISLATIVE JOURNAL TUESDAY, DECEMBER 14,1993 SESSION OF 1993 177TH OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY NO. 65 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES GUESTS INTRODUCED The House convened at 11 a.m., e.s.t. The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Chair is pleased to recognize the following guest pages from the Milton Hershey THE SPEAKER PRO TEMPORE School: Lewis Quilama, Bill Kilgore, Keith McAninch, Jody (GREGORY C. FAJT) PRESIDING McGuimess, Dee George, and Edith Hutchins. Also in the House gallery are the rest of the students of the Milton PRAYER Hershey School, along with their teacher, William Bitner. I REV. CLYDE W. ROACH, chaplain of the H~~~~ of would like to ask the House members to please give them a ~~~~~~t~ti~~~,from ~h~b~~~,pemylvania, offered the warm welcome. They are guests of Representative Tulli's. following prayer: Welcome to the hall of the House. Let us pray: COMMUNICATION FROM GOVERNOR Lord Your servant, Alfred, Lord Temyso~wrote that "Hope springs eternal from the human breast," and the The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursuant to Act 374 of 1974, psalmist said that "Weeping may endure for a night but joy I am hereby submitting for the record a communication from cometh in the morning." Governor Casey expressing his intentions to return to his ofice When during hours of grief and pain, misunderstandings and on Tuesday, December 21, 1993, at 12:Ol a.m. political upheavals, we thank You for giving us hope; for The following communication was submitted: giving us to understand that no matter what may befall us, we can still look to You for brighter tomorrows.