US Firearms Trafficking to Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War on the Mexican Drug Cartels

THE WAR ON MEXICAN CARTELS OPTIONS FOR U.S. AND MEXICAN POLICY-MAKERS POLICY PROGRAM CHAIRS Ken Liu Chris Taylor GROUP CHAIR Jean-Philippe Gauthier AUTHORS William Dean Laura Derouin Mikhaila Fogel Elsa Kania Tyler Keefe James McCune Valentina Perez Anthony Ramicone Robin Reyes Andrew Seo Minh Trinh Alex Velez-Green Colby Wilkason RESEARCH COORDINATORS Tia Ray Kathryn Walsh September 2012 Final Report of the Institute of Politics National Security Student Policy Group THE WAR ON MEXICAN CARTELS OPTIONS FOR U.S. AND MEXICAN POLICY-MAKERS POLICY PROGRAM CHAIRS Ken Liu Chris Taylor GROUP CHAIR Jean-Philippe Gauthier AUTHORS William Dean Laura Derouin Mikhaila Fogel Elsa Kania Tyler Keefe James McCune Valentina Perez Anthony Ramicone Robin Reyes Andrew Seo Minh Trinh Alex Velez-Green Colby Wilkason RESEARCH COORDINATORS Tia Ray Kathryn Walsh September 2012 Final Report of the Institute of Politics 2 National Security Student Policy Group Institute of Politics ABOUT THE INSTITUTE OF POLITICS NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY GROUP The Institute of Politics is a non-profit organization located in the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. It is a living memorial to President John F. Kennedy, and its mission is to unite and engage students, particularly undergraduates, with academics, politicians, activists, and policymakers on a non-partisan basis and to stimulate and nurture their interest in public service and leadership. The Institute strives to promote greater understanding and cooperation between the academic world and the world of politics and public affairs. Led by a Director, Senior Advisory Board, Student Advisory Committee, and staff, the Institute provides wide-ranging opportunities for both Harvard students and the general public. -

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) Link Directory Targeting Tomorrow’S Terrorist Today (T4) Through OSINT By: Mr

Creative Commons Copyright © Ben Benavides—no commercial exploitation without contract June 2011 Country Studies Public Places Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) Link Directory Targeting Tomorrow’s Terrorist Today (T4) through OSINT by: Mr. E. Ben Benavides CounterTerrorism Infrastructure Money Laundering Gang Warfare Open Source Intelligence is the non-cloak- and-dagger aspect of fact collecting. (Alan D. Tompkins) Human Smuggling Weapon Smuggling IEDs/EFPs Creative Commons Copyright © Ben Benavides—no commercial exploitation without contract Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................ 2 Comments ................................................................................................................................... 7 Open Source Intelligence (OSINT): What It Is and What It Isn’t ................................................... 8 How To Use Open Source Intelligence ........................................................................................ 9 Key Army Access Sites .............................................................................................................. 17 Must Haves References ............................................................................................................ 18 Core Open Source Intelligence Documents & Guides ........................................................... 18 MI Officer Students ............................................................................................................... -

In the Shadow of Saint Death

In the Shadow of Saint Death The Gulf Cartel and the Price of America’s Drug War in Mexico Michael Deibert An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK Copyright © 2014 by Michael Deibert First Lyons Paperback Edition, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available The Library of Congress has previously catalogued an earlier (hardcover) edition as follows: Deibert, Michael. In the shadow of Saint Death : the Gulf Cartel and the price of America’s drug war in Mexico / Michael Deibert. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7627-9125-5 (hardback) 1. Drug traffic—Mexican-American Border Region. 2. Drug dealers—Mexican-American Border Region. 3. Cartels—Mexican-American Border Region. 4. Drug control—Mexican- American Border Region. 5. Drug control—United States. 6. Drug traffic—Social aspects— Mexican-American Border Region. 7. Violence—Mexican-American Border Region. 8. Interviews—Mexican-American Border Region. 9. Mexican-American Border Region—Social conditions. I. Title. HV5831.M46D45 2014 363.450972—dc23 2014011008 ISBN 978-1-4930-0971-8 (pbk.) ISBN 978-1-4930-1065-3 (e-book) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence -

Justice-Reform

Mexico Institute SHARED RESPONSIBILITY: U.S.-MEXICO POLICY OPTIONS FOR CONFRONTING ORGANIZED CRIME Edited by Eric L. Olson, David A. Shirk, and Andrew Selee Mexico Institute Available from: Mexico Institute Trans-Border Institute Woodrow Wilson International University of San Diego Center for Scholars 5998 Alcalá Park, IPJ 255 One Woodrow Wilson Plaza San Diego, CA 92110-2492 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.sandiego.edu/tbi www.wilsoncenter.org/mexico ISBN : 1-933549-61-0 October 2010 The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan institution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television, and the monthly news-letter “Centerpoint.” For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. -

Gun Control Legislation

Gun Control Legislation William J. Krouse Specialist in Domestic Security and Crime Policy November 14, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32842 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Gun Control Legislation Summary Congress has debated the efficacy and constitutionality of federal regulation of firearms and ammunition, with strong advocates arguing for and against greater gun control. In the wake of the July 20, 2012, Aurora, CO, theater mass shooting, in which 12 people were shot to death and 58 wounded (7 of them critically) by a lone gunman, it is likely that there will be calls in the 112th Congress to reconsider a 1994 ban on semiautomatic assault weapons and large capacity ammunition feeding devices that expired in September 2004. There were similar calls to ban such feeding devices (see S. 436/H.R. 1781) following the January 8, 2011, Tucson, AZ, mass shooting, in which 6 people were killed and 14 wounded, including Representative Gabrielle Giffords, who was grievously wounded. These calls could be amplified by the August 5, 2012, Sikh temple shooting in Milwaukee, WI, in which six worshipers were shot to death and three wounded by a lone gunman. The 112th Congress continues to consider the implications of Operation Fast and Furious and allegations that the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) mishandled that Phoenix, AZ-based gun trafficking investigation. On June 28, 2012, the House passed a resolution (H.Res. 711) citing Attorney General Eric Holder with contempt for his failure to produce additional, subpoenaed documents related to Operation Fast and Furious to the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. -

501 Cmr: Executive Office of Public Safety

501 CMR: EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF PUBLIC SAFETY 501 CMR 7.00: APPROVED WEAPON ROSTERS Section 7.01: Purpose 7.02: Definitions 7.03: Development of Approved Firearms Roster 7.04: Criteria for Placement on Approved Firearms Roster 7.05: Compliance with the Approved Roster by Licensees 7.06: Appeals for Inclusion on or Removal from the Approved Firearms Roster 7.07: Form and Publication of the Approved Firearms Roster 7.08: Development of a Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.09: Criteria for Placement on Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.10: Large Capacity Weapons Not Listed 7.11: Form and Publication of the Large Capacity Weapons Roster 7.12: Development of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.13: Criteria for Placement on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.14: Appeals for Inclusion on the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.15: Form and Publication of the Formal Target Shooting Firearms Roster 7.16: Severability 7.01: Purpose The purpose of 501 CMR 7.00 is to provide rules and regulations governing the inclusion of firearms, rifles and shotguns on rosters of weapons referred to in M.G.L. c. 140, §§ 123 and 131¾. 7.02: Definitions As used in 501 CMR 7.00: Approved Firearm means a firearm make and model that passed the testing requirements of M.G.L. c. 140, § 123 and was subsequently approved by the Secretary. Included are those firearms listed on the current Approved Firearms Roster and those firearms approved by the Secretary of Public Safety that will be included on the next published Approved Firearms Roster. -

Drug Enforcement Administration FOIA Request Logs, FY2011-2016

Drug Enforcement Administration FOIA request logs, FY2011-2016 Brought to you by AltGov2 www.altgov2.org/FOIALand Received between 10/01/2010 and 09/30/2011 Request ID Received Date Closed Date Request Description Final Disposition 10/1/2010 4/30/2012 ANY AND ALL DOCUMENTS AND INFORMATION Granted/Denied in Part REGARDING AIRCRAFT BEECRAFT KING AIR 200 TAIL/ID #N642TF. ETC. 11-00001-F 8/2/2011 8/2/2011 INFORMATION CONCERNING THE "COCAINE Other Reasons - Records not reasonably 11-00002-F DRUG STATUE" described 6/22/2011 6/22/2011 INFORMATION REGARDING ILLEGAL DRUG Other Reasons - "Refusal to comply with other ACTIVITIES BETWEEN FLORIDA AND BILLERICA, requirements - Identification..." MA THAT WAS REPORTED TO DEA BY THE BOSTON, MA FIELD INTELLIGENCE SUPPORT 11-00003-F TEAMS (FIST) (SEPTEMBER 2005) 10/5/2010 6/29/2011 ANY AND ALL REPORTS, NOTICES OF LOSS Granted in full AND/OR FILINGS OF ANY SORT PERTAINING TO THE HAMPSTEAD PHARMACY, INC. AND/OR HAMPSTEAD MEDICAL CENTER LOCATED AT 14980 US WEST HIGHWAY 17, NORTH 11-00004-F HAMPSTEAD, NORTH CAROLINA 28443 10/5/2010 6/24/2011 COPIES OF THE "OATH OF OFFICE" FOR THE Granted/Denied in Part (b)(6), DEA SPECIAL AGENTS, FOR THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE , DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION'S LAKE MARY/HEATHROW 11-00005-F OFFICE IN FLORIDA 10/5/2010 6/27/2011 STRIDE DATA ON MARIJUANA FOR ALL YEARS Other Reasons - Request Withdrawn 11-00006-F AVAILABLE 10/5/2010 11/29/2010 ANY AND ALL RECORSD IN POSSESSION, Other Reasons - "Refusal to comply with other CUSTODY, OR CONTROL OF THE DRUG requirements - Identification..." ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION THAT REFER TO, RELATE, TO OR MENTION (b)(6), ETC. -

The U.S. Homeland Security Role in the Mexican War Against Drug Cartels

THE U.S. HOMELAND SECURITY ROLE IN THE MEXICAN WAR AGAINST DRUG CARTELS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 31, 2011 Serial No. 112–14 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–224 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia VACANCY BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director/Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT, INVESTIGATIONS, AND MANAGEMENT MICHAEL T. -

California State Laws

State Laws and Published Ordinances - California Current through all 372 Chapters of the 2020 Regular Session. Attorney General's Office Los Angeles Field Division California Department of Justice 550 North Brand Blvd, Suite 800 Attention: Public Inquiry Unit Glendale, CA 91203 Post Office Box 944255 Voice: (818) 265-2500 Sacramento, CA 94244-2550 https://www.atf.gov/los-angeles- Voice: (916) 210-6276 field-division https://oag.ca.gov/ San Francisco Field Division 5601 Arnold Road, Suite 400 Dublin, CA 94568 Voice: (925) 557-2800 https://www.atf.gov/san-francisco- field-division Table of Contents California Penal Code Part 1 – Of Crimes and Punishments Title 15 – Miscellaneous Crimes Chapter 1 – Schools Section 626.9. Possession of firearm in school zone or on grounds of public or private university or college; Exceptions. Section 626.91. Possession of ammunition on school grounds. Section 626.92. Application of Section 626.9. Part 6 – Control of Deadly Weapons Title 1 – Preliminary Provisions Division 2 – Definitions Section 16100. ".50 BMG cartridge". Section 16110. ".50 BMG rifle". Section 16150. "Ammunition". [Effective until July 1, 2020; Repealed effective July 1, 2020] Section 16150. “Ammunition”. [Operative July 1, 2020] Section 16151. “Ammunition vendor”. Section 16170. "Antique firearm". Section 16180. "Antique rifle". Section 16190. "Application to purchase". Section 16200. "Assault weapon". Section 16300. "Bona fide evidence of identity"; "Bona fide evidence of majority and identity'. Section 16330. "Cane gun". Section 16350. "Capacity to accept more than 10 rounds". Section 16400. “Clear evidence of the person’s identity and age” Section 16410. “Consultant-evaluator” Section 16430. "Deadly weapon". Section 16440. -

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” Quick Reference Guide

“BULLET BUTTON” / “ASSAULT WEAPON” quick Reference Guide PREREQUISITE FEATURES or telescoping stock, (D) A grenade launcher or the weapon without burning the bearer’s hand, QUICK TIPS OF AN ASSAULT WEAPON (AW) flare launcher, (E) A flash suppressor, or (F) A except a slide that encloses the barrel; (J) The FOR GUN OWNERS WITH The Penal Code now classifies the following as forward pistol grip. capacity to accept a detachable magazine at FIREARMS NOW an AW: PISTOLS: A semiautomatic pistol that does not some location outside of the pistol grip. have a fixed magazine but has anyone of the SHOTGUNS: While the change in the Penal CLASSIFIED AS RIFLES: A semiautomatic, centerfire rifle that following: (G) A threaded barrel, capable of ac- Code affects certain rifles and pistols, the DOJ does not have a fixed magazine but has any “ASSAULT WEAPONS” cepting a flash suppressor, forward handgrip, has taken the position that semiautomatic shot- one of the following: (A) A pistol grip that pro- or silencer; (H) A second handgrip; (I) A shroud guns required to be equipped with “bullet but- On January 1, 2017, the definition trudes conspicuously beneath the action of the that is attached to, or partially or completely en- tons” are also affected. of an “assault weapon” (“AW”) under weapon, (B) A thumbhole stock, (C) A folding California law was changed to include circles, the barrel that allows the bearer to fire firearms which were required to be equipped with a “bullet button” or similar KEY DEFINITIONS magazine locking device. This change does not affect ex- “FIXED MAGAZINE”- An ammunition feeding device contained in, or permanently attached to, a firearm in such a manner that the device cannot isting definitions of other types of AWs, be removed without disassembly of the firearm action. -

A Content Analysis of the Coverage of Gun Trafficking Along

A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE COVERAGE OF GUN TRAFFICKING ALONG THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER A Dissertation by OMAR CAMARILLO Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Holly Foster Committee Members, Sarah N. Gatson Jane Sell Alex McIntosh Head of Department, Jane Sell May 2015 Major Subject: Sociology Copyright 2015 Omar Camarillo ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzed how the media on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border portrayed the issue of gun trafficking’s into Mexico and its impact on Mexico’s border violence. National newspapers from both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border were analyzed from January 2009 through January 2012, The New York Times for the U.S. and El Universal for Mexico, which resulted in a sample of 602 newspaper articles. Qualitative research methods were utilized to collect and analyze the data, specifically content analysis. Drawing on a theoretical framework of social problems and framing this study addressed how gun trafficking along the U.S.-Mexico border impacted the drug related violence that is ongoing in Mexico, how gun trafficking was portrayed as a social problem by the media, and how the media depicted the victims of drug related violence. This study revealed six framing devices, “the blame game,” “worthy and unworthy victims,” “positive aspects of gun trafficking,” “negative aspects of gun trafficking,” “indirect mention of gun trafficking,” and “direct mention of gun trafficking” that were utilized by The New York Times and El Universal to discuss and frame the issue gun trafficking into Mexico and its impact on Mexico’s border violence. -

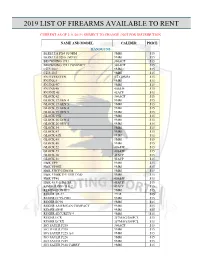

2019 List of Firearms Available to Rent

2019 LIST OF FIREARMS AVAILABLE TO RENT CURRENT AS OF 2/11/2019 | SUBJECT TO CHANGE | NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS BERETTA PX4 STORM 9MM $15 BERETTA 92FS | M9A1 9MM $15 BROWNING 1911 380ACP $15 BROWNING 1911 COMPACT 380ACP $15 CZ P-10 C 9MM $15 CZ P-10 F 9MM $15 FN FIVESEVEN 5.7X28MM $15 FN FNS-9 9MM $15 FN FNS-9C 9MM $15 FN FNS-40 40S&W $15 FN FNX-45 45ACP $15 GLOCK 42 380ACP $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 17 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 19 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 19X 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 4 9MM $15 GLOCK 26 GEN 5 9MM $15 GLOCK 34 9MM $15 GLOCK 43 9MM $15 GLOCK 43X 9MM $15 GLOCK 45 9MM $15 GLOCK 48 9MM $15 GLOCK 22 40S&W $15 GLOCK 23 40S&W $15 GLOCK 36 45ACP $15 GLOCK 21 45ACP $15 H&K VP9 9MM $15 H&K VP9SK 9MM $15 H&K P30 V-3 DA/SA 9MM $15 H&K P30SK V-1 LEM DAO 9MM $15 H&K VP40 40S&W $15 H&K 45 V-1 DA/SA 45ACP $15 KIMBER PRO TLE 2 45ACP $15 REMINGTON RP9 9MM $15 RUGER SR-22 22LR $15 RUGER LC9S-PRO 9MM $15 RUGER EC9S 9MM $15 RUGER AMERICAN COMPACT 9MM $15 RUGER SR9E 9MM $15 RUGER SECURITY-9 9MM $15 RUGER LCR 357MAG/38SPCL $15 RUGER LCRX 357MAG/38SPCL $15 SIG SAUER P238 380ACP $15 SIG SUAER P938 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P225 A-1 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P226 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P229 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P320 CARRY 9MM $15 NAME AND MODEL CALIBER PRICE HANDGUNS SIG SAUER P320–M17 9MM 9MM $15 SIG SAUER P365 9MM $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P22 COMPACT 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON REVOLVER 617 22LR $15 SMITH & WESSON BODYGUARD 380 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P380 SHIELD EZ 380ACP $15 SMITH & WESSON M&P9 M2.0 5” FDE 9MM $15 SMITH &