Winter 2018 H Volume 22 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downtown Austin Plan

Draft DOWNTOWN PARKS AND OPEN SPACE MASTER PLAN Downtown Austin Plan Prepared for the City of Austin by ROMA Austin and HR&A Advisors Revised January 19, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Purpose of Plan ...............................................................................................................................1 Relati onship to Downtown Austi n Plan ..........................................................................................1 Vision Statement .............................................................................................................................1 Challenges to Address .....................................................................................................................2 Summary of Master Plan Recommendati ons .................................................................................2 General Policy Prioriti es ............................................................................................................2 Fees and Assessments ...............................................................................................................3 Governance and Management ..................................................................................................4 Priority Projects .........................................................................................................................5 Funding Prioriti es ............................................................................................................................5 -

Mexican American Resource Guide: Sources of Information Relating to the Mexican American Community in Austin and Travis County

MEXICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE: SOURCES OF INFORMATION RELATING TO THE MEXICAN AMERICAN COMMUNITY IN AUSTIN AND TRAVIS COUNTY THE AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY Updated by Amanda Jasso Mexican American Community Archivist September 2017 Austin History Center- Mexican American Resource Guide – September 2017 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use so that customers can learn from the community’s collective memory. The collections of the AHC contain valuable materials about Austin and Travis County’s Mexican American communities. The materials in the resource guide are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This guide is one of a series of updates to the original 1977 version compiled by Austin History staff. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals, support groups and Austin History Center staff. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the Find It: Austin Public Library On-Line Library Catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing individual items in the collection with entries under author, title, and subject. These tools lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be very difficult to find. It must be noted that there are still significant gaps remaining in our collection in regards to the Mexican American community. -

City of Austin General and Special Election November 3, 2020

CITY OF AUSTIN GENERAL AND SPECIAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 3, 2020 ORDINANCE NO. 20200812-009 AN ORDINANCE ORDERING A GENERAL MUNICIPAL ELECTION TO BE HELD IN THE CITY OF AUSTIN ON NOVEMBER 3, 2020, FOR THE PURPOSE OF ELECTING CITY COUNCIL MEMBERS (SINGLE MEMBER DISTRICTS) FOR DISTRICT 2, DISTRICT 4, DISTRICT 6, DISTRICT 7, AND DISTRICT 10; ORDERING A SPECIAL ELECTION FOR THE PURPOSE OF SUBMITTING A PROPOSED TAX RATE THAT EXCEEDS THE VOTER APPROVAL RATE FOR THE PURPOSE OF FUNDING AND AUTHORIZING THE PROJECT CONNECT TRANSIT SYSTEM; PROVIDING FOR THE CONDUCT OF THE MUNICIPAL GENERAL AND SPECIAL ELECTIONS; AUTHORIZING THE CITY CLERK TO ENTER INTO JOINT ELECTION AGREEMENTS WITH OTHER LOCAL POLITICAL SUBDIVISIONS AS MAY BE NECESSARY FOR THE ORDERLY CONDUCT OF THE ELECTIONS; AND DECLARING AN EMERGENCY. BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF AUSTIN: PART 1. A general municipal election shall be held in the City of Austin on November 3, 2020. At the election there shall be elected by the qualified voters of the City five City Council Members (single member districts) for District 2, District 4, District 6, District 7, and District 10. The candidates for Districts 2, 4, 6, 7, and 10 shall meet all requirements, shall be residents of their respective districts , and shall be elected by majority vote of voters residing in each respective district. PART 2. A special municipal election shall be held in the City on November 3, 2020, to submit to the voters of the City a proposed tax rate that exceeds the voter approval rate, for the purpose of funding and authorizing a fixed rail transit system known as Project Connect. -

Blue/Gold Line LPA Summary

Your Plan, Your Blue Line & Gold Line Summary Report April 2020 CONTENTS WHY PLAN THE BLUE LINE & GOLD LINE 1 CORRIDOR PLANNING & ROUTE EVOLUTION 2 HOW THE LRT SYSTEM COMES TOGETHER 3 EXPLORING OUR OPTIONS FOR A TUNNEL 5 HOW WE GOT HERE 6 WHO IS INVOLVED 7 WHAT WE HEARD 9 HOW IT COULD BE IMPLEMENTED 10 HOW IT ALL COMES TOGETHER 11 BLUE LINE AT A GLANCE 12 GOLD LINE AT A GLANCE 13 WHAT’S IN IT FOR YOU 14 WHAT’S NEXT 16 WHY PLAN THE BLUE LINE & GOLD LINE THE NEED AND THE VISION Capital Metro began developing the Project Connect Vision In 2019, the Austin City Council approved the Austin Strategic Plan in 2016. The need for the Project Connect vision is Mobility Plan, which establishes a policy goal to quadruple the result of Central Texas’ booming population which is the share of commuters who use transit by 2039. The Project projected to double by 2040. This growth will cause additional Connect Vision Plan is included as an integral part of the strain on the roadway network, result in increased travel ASMP, and both initiatives provide a way forward for solving times and travel costs, decrease our mobility, hinder our future mobility challenges the region faces. region’s economic health, and threaten our air quality. Constructing and operating HCT is an effective tool to address In December 2018, the Capital Metro Board of Directors the region's growth pressures, improve mobility, and connect approved the Project Connect Vision Plan, which identified Central Texans to their travel destinations. -

Fall 2020 H Volume 24 No. 2 Continued on Page 3 S We Celebrate Sixty Years of Our Preservation Merit Awards Program, We're Gr

Fall 2020 h Volume 24 No. 2 A s we celebrate sixty years of our video shorts that bring these buildings professionals from the preservation, Preservation Merit Awards program, to life through pictures and narration design, and nonprofit worlds who we’re grateful to our 2020 recipients for (@preservationaustin on Facebook and together selected exemplary projects bringing together so much of what we love Instagram). with real community impact: Erin about Austin – iconic brands investing in Dowell, Senior Designer, Lauren Ramirez local landmarks, modest buildings restored During these uncertain times it’s more Styling & Interiors; Melissa Ayala, with big impact, homeowners honoring important than ever to celebrate these Community Engagement & Government the legacies of those who came before, places and their stories, past and Relations Manager, Waterloo Greenway and community efforts that celebrate our present. Thank you for your membership Conservancy; Murray Legge, FAIA, Murray shared heritage. These projects represent and for your continued support – you Legge Architecture; Elizabeth Porterfield, what historic preservation looks like in the make all of this important work possible. Senior Architectural Historian, Hicks & 21st century. We hope you’ll enjoy learning Company; and Justin Kockritz, Lead about them as much as we did, and that Many thanks to our incredible 2020 Project Reviewer, Federal Programs, Texas you’ll follow us on social media for special Preservation Merit Awards Jury, including Historical Commission. Continued on page 3 HILL COUNTRY DECO: LECTURE 2020-2021 Board of Directors Thursday, November 12 7pm to 8:15pm Free, RSVP Required Virtual/Zoom h EXECUTIVE coMMITEE h Using vibrant original photography and historic images, authors Clayton Bullock, President Melissa Barry, VP David Bush and Jim Parsons will trace the history and evolution of Allen Wise, President-Elect Linda Y. -

Live Music Capital of the World® Austin Eats & Drinks

Insider Guide 2021 Outdoor lovers find their bliss in AUSTINAustin PAGE 20 GET OUTSIDE LIVE MUSIC CAPITAL OF THE WORLD® PAGE 12 AUSTIN EATS & DRINKS PAGE 16 14 TEXAS HILL COUNTRY TOWNS WORTH A STOP PAGE 49 BE PART OF OUR HISTORY Paramount Theatre Cisco’s Restaurant Bakery & Bar Driskill Hotel Oakwood Cemetery We’re a city with no shortage of history or legend. In fact, both are very much alive throughout Austin. As you go exploring, take note that history isn’t just found in our architecture, monuments and museums. Delve into the backstory of our fascinating town, where you can discover everything from art and history museums to lush parks, still kickin’ honky-tonks and restaurants that have proudly served up meals to generations of locals. Visit www.austintexas.org/things-to-do/history STAY A PART OF AUSTIN’S HILL COUNTRY Whatever you’re apart of. Stay that way. FOUR CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF COURSES | MOKARA SPA | SEVEN DINING OPTIONS 76,192 SQUARE FEET OF MEETING AND EVENT SPACE | OMNIHOTELS.COM/BARTONCREEK 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 ROWINGDOCK.COM 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282 SUPS KAYAKS CANOES visitaustin.org President & CEO Tom Noonan Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Marketing & Design Coordinator Emily Carr Director of Marketing Tiffany Dixon Kerr Marketing Manager, Digital & Content Christine Felton Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Marketing Manager Silvia Krawczyk Tourism & Marketing Specialist Allison Lamell Director of Music Marketing Omar Lozano Director of Content & Digital Marketing Susan Richardson Marketing Manager, Digital Holland Taylor AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. -

Of2 Graves, Tyrone

Page 1 of2 Graves, Tyrone From: Martinez, Mike [Council Member] Sent: Saturday, April 17, 20106:50 AM To: Nathan, Mark; Council Executive Assistants; Council Executive Secretaries Subject: RE: First Irregular Council Staffer Wii Tennis Invitational this stinks to high heaven. the guy that proposed the event and asks me to sponsor iLends up winning. what do I look like? some low life Latino from the East side?!? I'm officiating next time .... and Alejandro says he wants to play in the next one. Says he would have taken it for sure. I tend to agree. MM From: Nathan, Mark Sent: Fri 4/16/2010 5:54 PM To: Council Executive Assistants; Council Executive Secretaries; Martinez, Mike [Council Member] Subject: RE: First Irregular Council Staffer Wii Tennis Invitational In a completely expected development, I was the winner of the First Irregular Council Staffer Wii Tennis Invitational. I will now spend the two years trying in vain to collect my prize money from Martinez. Thanks to all players (and better luck next time). Have a good weekend, all! MN. From: l'lathan, lV1ark Sent: Wednesday, April 14, 20103:13 PM To: Council Executive Assistants; Council Executive Secretaries Subject: First Irregular Council Staffer Wii Tennis Invitational Friends: In honor of all your hard work and accomplishments on behalf of the citizens of Austin, we invite you to join us for a little fun and friendly competition this Friday afternoon: It's the First Irregular Council Staffer Wii Tennis Invitational! This exciting tournament will be held in the mayor's conference room beginning at 4:00 PM on Friday afternoon. -

Proposition Two for Light Rail

ORDINANCE NO. ___________ PART ____. The Council establishes that the following bond proposition shall be presented to the voters at the special bond election on November 8, 2016: PROPOSITION TWO Shall the City Council of the City of Austin, Texas be authorized to issue general obligation bonds and notes of the City for transportation and mobility purposes, to wit: planning, designing, engineering, acquiring, constructing, reconstructing, renovating, improving, operating, maintaining and equipping rail systems, facilities and infrastructure, including a fixed rail transit system to be operated by Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority (which may spend its funds to build, operate and maintain such system) servicing the Guadalupe and North Lamar Corridor, downtown Austin, the State Capitol complex, Crestview Station, the Department of Public Safety, the State of Texas North Austin Complex, the Austin State Hospital, Republic Square Station, Seton Medical Center, the University of Texas, the Travis County Central Campus, and surrounding neighborhoods; roadway improvements related to such rail systems, facilities and infrastructure; acquiring land and interests in land and property necessary therefor; and all matters necessary or incidental thereto; with the bonds and notes to be issued in one or more series or issues, in the aggregate principal amount of $397,500,000, to mature serially or otherwise and bear interest at a rate or rates not to exceed the respective limits prescribed by law at the time of issuance, and to be sold at the price or prices as the City Council determines and shall there be levied and pledged, assessed, and collected annually ad valorem taxes on all taxable property in the City in an amount sufficient to pay the annual interest on the bonds and notes and to provide a sinking fund to pay the bonds and notes at maturity? PART ____. -

Greater Austin Area Park Ln 35 Gibson St 183 Fm 1325 Rm 620

Attractions 60 23 ROUND ROCK Congress Avenue Blanton Museum of Art Austin History Center 1 Bat Bridge 14 The nation’s largest university 28 This research center for Austin More than 1.5 million bats -owned art collection includes and Travis County has fly out from beneath the more than 17,000 works. archives dating from 1839. bridge each night at dusk from March - October. Harry Ransom Center The Contemporary Austin 27TH ST 15 29 – Jones Center SAN JACINTO BLVD This center houses the world’s RIO GRANDE ST 58 Plaza Saltillo first photograph, a rare Through statewide exhibitions SALADO ST 2 DEAN KEETON ST This East Austin community Gutenberg Bible, Watergate and programs, The center is the site of annual papers, and more. Contemporary Austin helps CENTRAL AUSTIN 26TH ST Diez y Seis and Cinco de nurture artists’ careers. DISTRICT Mayo celebrations. UT Tower W 26TH ST 16 This 307-foot tower, Emma S. Barrientos 19 Austin Convention Center constructed in 1937, is the 30 Mexican-American WHITIS AVE T S 3 Y With nearly 900,000 square most visible landmark on the Cultural Center IT N 24TH ST I 24 R feet, this facility accom- UT Austin campus. Mexican-American arts and T 25 S A N modates major conventions heritage are highlighted with J A C and large consumer shows. Frank Erwin Center exhibits and performances. I 23RD ST DR DEDMAN ROBERT GUADALUPE ST N SPEEDWAY T 17 O SAN ANTONIO ST INN Head to this arena for Longhorn NUECES ST E R B RIO GRANDE ST C L Mexic-Arte Museum A V Palmer Events Center basketball games, touring 24TH ST M D P 4 31 U CLYDE LITTLEFIELD DR Stop in for exhibits of S SAN GABRIEL ST Overlooking Lady Bird Lake, music concerts, and more. -

Historic Austin Location Since Its 1892 Renovation by Prominent Local Banker, Ira Evans

ONLINE AUSTIN HISTORY RESOURCES Austin History Center austinhistorycenter.org Austin Historical Survey Wiki austinhistoricalsurvey.org Austin Museum Partnership austinmuseums.org City of Austin austintexas.gov Preservation Austin preservationaustin.org Texas Historical Commission thc.state.tx.us Texas State Historical Association tshaonline.org/handbook Our Visitor Center welcomes you to Austin with maps, city information and walking tours. AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St. 512-478-0098 | austintexas.org Historic Sixth Street and The Driskill Hotel. DISCOVER AUSTIN’S RICH HISTORY. With 180 sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places, including 17 historic districts and 2 National Historic Landmarks, Austin puts you at the heart of Texas history. From the Texas State Capitol to the Paramount Theatre, The Driskill Hotel to Barton Springs, the heritage of the Lone Star State lives and breathes throughout our city. We invite you to explore, experience and enjoy Austin’s many memorable attractions and make our history part of yours. THE TEXAS STATE 1 CAPITOL COMPLEX TEXAS STATE CAPITOL BUILDING Detroit architect Elijah E. Myers’ 1888 Renaissance Revival design echoes that of the U.S. Capitol, but at 302 feet, the Texas State Capitol is 14 feet higher. The base is made of rusticated Sunset Red Texas granite; the dome is made of cast iron and sheet metal, topped by a Goddess of Liberty statue. The seals on the south façade commemorate the six governments that have ruled in Texas over time: Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the Confederate States of America and the United States. Myers also designed the state capitols of Michigan and Colorado. -

Bouldin Survey Report 151211

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Preservation Central, Inc. appreciates the people and organizations who have contributed to the Bouldin Creek Neighborhood Association Historic Resources Survey. In particular, we wish to thank Cory Walton for his perseverance and assistance in keeping us on track through a challenging survey season. We also wish to thank volunteer Trude Cables for her dedication to getting the survey completed and for her stamina doing field work in August and September when the temperature soared, as well as for her data entry service. Finally, we wish to thank the members of the Bouldin Creek Neighborhood Association who voted to fund this project to identify and minimally document all cultural resources (buildings, structures, objects, and sites) in the project area boundaries. This effort has resulted in the survey of 1,306 cultural resources, 694 of which date to the historic period (c. 1850-1965). ABSTRACT In January 2015, the Bouldin Creek Neighborhood Association retained the services of Preservation Central, Inc., an Austin historic preservation consulting firm, to conduct an architectural survey within the association’s boundaries, an area roughly bounded by Barton Springs Road on the north, Oltorf on the south, S. Congress Avenue on the east, and the Union Pacific Railroad tracks on the west. Preservation Central first conducted a “windshield” or driving survey of cultural resources within the Bouldin Creek Neighborhood. The windshield survey identified a slightly smaller area for a reconnaissance survey due to fewer concentrations of historic properties, particularly in the area between S. Fifth Street and S. Lamar Blvd. The revised survey area was roughly bounded by Bouldin Creek on the north, the north side of Oltorf on the south, S. -

TA-1985-05-06.Pdf

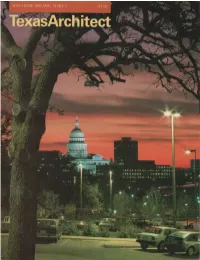

~--~--.!!-~ .... ,.. Wh~ are Te,&as arehiteets speeif~ing Solaroll® more than an~ other e,&terior shutter stem? Because Solaroll® is the answer to practically every Another reason is our services to architects, such as concern an architect may have regarding the vulnerability assistance at preliminary-design time, and at the budget of sliding glass doors and windows. Solaroll® provides preparation stage, on projects ranging from single the functions of storm protection ... security ... privacy ... family homes to multi-story structures. shade and insulation. And yet, the appearance of our Why are more and more architects specifying Sola roll®? system is complementary to any architectural design. II .. ,an the rest. Au•tln: 2056 Stassney Lane, Austin 78745, 512 282 4831 Corpu. Christi: 3833 So. Staples, Suite 67, Corpus Christa 78411, 512/851 8238 Dallas/Ft. wOrth: 4408 N Haltom, Ft Worth 76117, 817/ 485 5013 Hou•ton: 2940 Patao Dr., Houston 77017, 713/643 2677 Lonelllew: 105 Gum Springs Road, Longview 75602, 214/ 757 4572 Pharr: 805 North Cage, Pharr 78577, 512/787 5994 For complete information, call or write ~ for our 40-page Technical Catalog 553 Solaroll Pompano Beach, Florida C1rclo 2 on Reader Inquiry Card TC""\.D Am1i1ec1 u ,-J,lislwtl JU ,._,.,.., CO'.\ITENTS ,-,, br dtr Tum Son,n tf Arclrm<u tljfrWor,--tfllwT,...,R-,-IJ/ dw..i-,..--1-t,(,t,mbftu On EMERGING AUSTIN Ttnlor H.,., ALI Euntm-, lK, PrnidrM EDITOlt Jori ""'",. Ban., M .._, 11.Gl'-G EOrTOlt O.Z.-w8rool., ASSOClll.TF. EDITOR /1,r,)....,..,.. ASS<lC11>.TF. P\/BLISHF.R Robnt/1 F",d,I CtROJl.ATIO' M.,,AGER u.A""~ Pl Bl.JCATlO'-!> ASSl!>TA.'-i fDITORIAI.