Veerashaiva Temple Architecture, Sculpture and Iconography SHUBHA.C.S Asst Professor Dept of History GFG College, Hosadurga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptation of the List of Backward Classes Castes/ Comm

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA ABSTRACT Backward Classes Welfare Department – Adaptation of the list of Backward Classes Castes/ Communities and providing percentage of reservation in the State of Telangana – Certain amendments – Orders – Issued. Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department G.O.MS.No. 16. Dated:11.03.2015 Read the following:- 1. G.O.Ms.No.3, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.14.08.2014 2. G.O.Ms.No.4, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.30.08.2014 3. G.O.Ms.No.5, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.02.09.2014 4. From the Member Secretary, Commission for Backward Classes, letter No.384/C/2014, dated.25.9.2014. 5. From the Director, B.C. Welfare, Telangana, letter No.E/1066/2014, dated.17.10.2014 6. G.O.Ms.No.2, Scheduled Caste Development (POA.A2) Department, Dt.22.01.2015 *** ORDER: In the G.O. first read above, orders were issued adapting the relevant Government Orders issued in the undivided State of Andhra Pradesh along with the list of (112) castes/communities group wise as Backward Classes with percentage of reservation, as specified therein for the State of Telangana. 2. In the G.O. second and third read above, orders were issued for amendment of certain entries at Sl.No.92 and Sl.No.5 respectively in the Annexure to the G.O. first read above. 3. In the letters fourth and fifth read above, proposals were received by the Government for certain amendments in respect of the Groups A, B, C, D and E, etc., of the Backward Classes Castes/Communities as adapted in the State of Telangana. -

Jyotirlinga Temple Tour

12- Jyotirlinga Temple Tour Day 1 – Arrive Kolkatta Arrive at Kolkata Airport and transfer to the hotel for overnight stay. Day 2 – Kolkatta / Kiul – Overnight train Morning sightseeing tour of Kolkata city. Rest of the afternoon at leisure. Evening transfer to Howrah Railway Station to board overnight train for Kiul. Day 3 – Kiul – Visit Baijnath Temple Arrive early in the morning at Kiul Railway Station. arrival and continue driving to Deogarh to visit Baijnath temple. Later after visit continue driving to Bodhgaya for overnight stay. Basic accommodation is available. Day 4 – Bodhgaya / Varanasi Morning visit Buddhist sites at Bodhgaya. Afternoon drive to Varanasi and check in at the hotel. Overnight stay. Day 5 – Varanasi Early morning proceed to River Ganges for holy dip and have boat ride. Temple of Lord Viswanath is situated in Varanasi. Known formerly as Kashi or Benares, this ancient city set on the banks of the river Ganga, is one of the holiest cities in India. Being one of the oldest living and most holy city’s in India, Varanasi attracts a lot of tourists. Day 6 – Varanasi / Haridwar – Overnight train Transfer to Railway Station in time to board overnight train for Haridwar. Overnight on board. Day 7 – Arrive Haridwar / Rishikesh Arrive Haridwar in morning. Arrival and proceed for the temple tour of Haridwar and then drive for Rishikesh. Overnight stay. Day 8 – Rishikesh / Hanuman Chati Morning drive to Hanuman Chatti. Check in at Guest House / lodge on arrival. Overnight at the Lodge. Day 9 – Hanuman Chatti / Yamunotri / Hanujman Chatti Proceed for same day excursion to Yamunotri- temple dedicated to Goddess Yamuna . -

Somnath Travel Guide - Page 1

Somnath Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/somnath page 1 devotion at the Somnath Temple. It finds Max: Min: Rain: 31.79999923 19.79999923 2.20000004768371 mention in the Hindu puranas and the 7060547°C 7060547°C 6mm Somnath Mahabharata. Literally translated as the Apr Home to one of the 12 sacred Shiva "Lord of the Moon," the town and its temple Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. celebrate the most auspicious Karthik Jyotirlinga's in India, the grandeur Max: Min: Rain: 0.0mm Poornima (or full-moon) in the month of 32.09999847 22.79999923 of Somnath is sure to take your 4121094°C 7060547°C November/ December with full fervour and May breath away. The lofty shikharas flavour. The reverberating sounds of Shiv Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. add colour to the town and flavour bhajans and the legend, culture and Max: Min: Rain: to the lives of people who visit it. tradition surrounding it, will accompany you 32.79999923 26.20000076 4.40000009536743 during your entire stay at Somanth. It has 706055°C 2939453°C 2mm been popularly dubbed as the "shrine Jun eternal," for its ability to stand tall in the Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, umbrella. face of destruction - it's been rebuilt six Famous For : City Max: 32.5°C Min: Rain: times. 27.39999961 134.800003051757 8530273°C 8mm Somnath is famous for its grand Shiva When To Jul temple, one of the 12 revered Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Jyotirlingas, located right on the shore of the umbrella. Arabian Sea, in Max: Min: Rain: VISIT 30.70000076 26.60000038 269.799987792968 Junagadh District. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Demand for Separate Lingayat Religion

Demand for Separate Lingayat religion Why in news? \n\n The Karnataka government decided to recommend to the Centre to grant religious minority status to the Lingayat community. \n\n What is the state government decision? \n\n \n Lingayats account for nearly 17 per cent of the state’s population. \n The demand for separate religion tag and minority status is a long pending demand of the Lingayat community. \n The State Cabinet has decided to accept the recommendations of the state minority commission in this regard. \n The religious minority recognition will thus be granted under the Karnataka Minorities Act. \n The status will cover two factions of the community — Lingayats and Veerashaiva Lingayats. \n The State Cabinet also decided to forward the demand to the Centre for notifying under the Central Minority Commission Act. \n \n\n Who are the Lingayats? \n\n \n The Lingayats are strict monotheists. \n They instruct the worship of only one God, namely, Linga (Shiva). \n ‘Linga’ here does not mean Linga established in temples. \n It is rather the universal consciousness qualified by the universal energy (Shakti). \n Status - Lingayats are currently classified as a Hindu sub-caste called “Veerashaiva Lingayats”. \n There is a general misconception that Lingayatism is a subsect of Shaivism, which is itself a sect of Hinduism. \n There is also a misconception that the Lingayats are Shudras. \n But textual evidence and reasoning suggests that Lingayatism is not a sect or subsect of Hinduism, but an independent religion. \n \n\n How did it evolve? \n\n \n The community actually evolved from a 12th century movement led by social reformer and philosopher-saint Basavanna. -

Temple Foods of India’’

Report on stall of “Temple foods of India’’ National “Eat Right Mela” from 14th to 16th December, 2018 at IGNCA near India Gate, New Delhi The first National “Eat Right Mela” is being organized from 14th to 16th December, 2018 at IGNCA near India Gate, New Delhi. This Mela is being held along with the established and well-known ‘Street Food Festival’ organized by NASVI since the past 10 years. One of the attractions was the stall on “Temple Foods of India” under the pavilion “Flavours of India” which showcased cuisines of India’s most famous temples and the variety of different prasad offered to pilgrims. Following are 13 famous Temples from across India participated in the festival: S. No. Name of temple 1 Arulmigu Meenakshi Sundareshwarar Temple, Madura i, Tamil Nadu 2 Dhandayuthapani Swamy Temple,Palani,Tamil Nadu 3 Ramanathaswamy Temple, Rameshwaram, Tamil Nadu 4 Arunachaleshwarar Temple, Thiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu 5 ISKCON Temple, Delhi 6 Chittaranjan Park Kali Mandir, Delhi 7 Gurudwara, Delhi 8 Somnath Temple, Gujarat 9 Shree Kashtubhanjan Hanumanji Temple, Gujarat 10 Ambaji Temple, Gujarat 11 Swaminarayan temple BAPS, Maharashtra 12 Shirdi Sai Baba Temple, Maharashtra 13 Shrinathji Mandir Nathdwara, Rajasthan Some of the temples are associated with FSSAI under BHOG (Blissful Hygienic Offering to God) which focuses on the hygienic preparation of prasad and training & capacity building of the Temple food ecosystem to ensure the same. Day 1 at Eat Right Mela 14 dec to 16 dec, 2018 Four Temples from Tamil Nadu had brought different kind of Prasad. And these temples have already implemented FSMS in their temples. -

Enchanting Gujarat

Enchanting Gujarat 06 Nights / 07 Days 2N Dwarka – 2N Somnath (via. Porbandar) - 2N Diu PACKAGE HIGHLIGHTS: In Dwarka, visit Nageshwar Jyotirlinga, Rukmini Temple and Dwarkadhish Temple Enroute visit of Porbandar – Visit Kirti Temple In Somnath, visit Triveni Sangam, Bhalka Tirth and Geeta Mandir Chowpatty In Diu, visit St. Paul Church & Diu Museum. Sightseeing tours by private air- conditioned vehicle Start and End in Rajkot ITINERARY: Day 01 Arrival in Rajkot – Dwarka (230 kms / 4.5 hours) Meet our representative upon arrival Rajkot and proceed to Dwarka. On arrival check into your hotel and enjoy rest of the day at leisure. Overnight in Dwarka. Day 02 Sightseeing in Dwarka After breakfast, take a dip in the sacred River Gomti River according to the customs of the place. Visit the Nageshwar Jyotirlinga, which is one of the 12 Jyotirlingas that are mentioned in the Shiva Purana. Also visit Gopi Talav pond nearby and get to learn about the stories of Lord Krishna and the Gopis. Continue further to visit the island of Bet Dwarka. On your way back, visit the Rukmini Temple and other famous temples in the coastal area. Witness the famous evening aarti at the Dwarkadhish Temple, before returning to the hotel. At the end of a well- spent spiritual day, return to your hotel for overnight stay in Dwarka. Day 03 - Dwarka to Somnath via Porbandar (230 kms / 4.5 hours) After breakfast, check out from the hotel and proceed from Dwarka to Porbandar early in the morning. Visit the Kirti Temple, the memorial built in honour of Mahatma Gandhi. -

Veerashivasabha.Pdf

Akhila Bharatha Veerashaiva Mahasabha was established in 1904 by Pujya Sri Hanagal Kumaraswamiji. It is working for the organization and development of Veerashaiva-Lingayath Community. Presently, the Mahasabha has more than 75,000 members and has its own head- quarters'Veerashaiva-Lingayatha Bhavan' at Bengaluru. In order to unify Veerashaiva- Lingayaths socially and religiously, 21 conventions have been held till date. The 22nd Convention of the Mahasabha will be held on 17th , 18 th and 19 th April 2011 at Suttur Sri Kshethra, Mysore District. Jagadguru Sri Veerasimhasana Mahasamstana Math of Srikshethra Suttur is one of the most ancient religious maths. It is situated on the bank of the river Kapila amidst beautiful green surroundings. The districts of Mysore, Mandya, Chamarajanagar and Kodagu, where the Veerashaiva tradition, culture and bonding are still rich, are hosting this convention, with great enthusiasm and fervour. In the three days’ convention, an exhibition depicting the road traversed by Veerashaiva- Lingayatha Community has been organized. Various seminars on religious, social, economic and cultural issues are arranged. Cultural programmes will be held in the evening. People belonging to Veerashaiva-Lingayatha community from all over the world are expected to participate in this historic convention. All are cordially invited to participate in this convention in large numbers and make this a grand success. 17 April 2011 Sunday Procession 8.00 am The procession of the President of the Akhila Bharatha Veerashaiva Mahasabha, along with Nandidhwaja and folk cultural troupes starts from Suttur Srimath and will reach Sri Siddhalinga Shivayogi Mantapa. Flag Hoisting 10.00 am National Flag Shatsthala Dhwajarohana Sri H. -

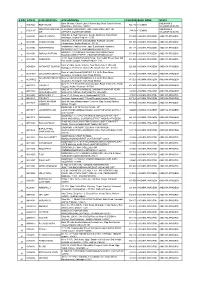

S No Atm Id Atm Location Atm Address Pincode Bank

S NO ATM ID ATM LOCATION ATM ADDRESS PINCODE BANK ZONE STATE Bank Of India, Church Lane, Phoenix Bay, Near Carmel School, ANDAMAN & ACE9022 PORT BLAIR 744 101 CHENNAI 1 Ward No.6, Port Blair - 744101 NICOBAR ISLANDS DOLYGUNJ,PORTBL ATR ROAD, PHARGOAN, DOLYGUNJ POST,OPP TO ANDAMAN & CCE8137 744103 CHENNAI 2 AIR AIRPORT, SOUTH ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLANDS Shop No :2, Near Sai Xerox, Beside Medinova, Rajiv Road, AAX8001 ANANTHAPURA 515 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 3 Anathapur, Andhra Pradesh - 5155 Shop No 2, Ammanna Setty Building, Kothavur Junction, ACV8001 CHODAVARAM 531 036 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 Chodavaram, Andhra Pradesh - 53136 kiranashop 5 road junction ,opp. Sudarshana mandiram, ACV8002 NARSIPATNAM 531 116 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Narsipatnam 531116 visakhapatnam (dist)-531116 DO.NO 11-183,GOPALA PATNAM, MAIN ROAD NEAR ACV8003 GOPALA PATNAM 530 047 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 6 NOOKALAMMA TEMPLE, VISAKHAPATNAM-530047 4-493, Near Bharat Petroliam Pump, Koti Reddy Street, Near Old ACY8001 CUDDAPPA 516 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Bus stand Cudappa, Andhra Pradesh- 5161 Bank of India, Guntur Branch, Door No.5-25-521, Main Rd, AGN9001 KOTHAPET GUNTUR 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta, P.B.No.66, Guntur (P), Dist.Guntur, AP - 522001. 8 Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW8001 GAJUWAKA BRANCH 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 9 Gajuwaka, Anakapalle Main Road-530026 GAJUWAKA BRANCH Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW9002 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH -

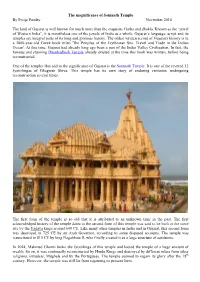

The Magnificence of Somnath Temple by Pooja Pandey November 2016

The magnificence of Somnath Temple By Pooja Pandey November 2016 The land of Gujarat is well known for much more than the exquisite Garba and dhokla. Known as the “jewel of Western India”, it is nonetheless one of the jewels of India as a whole. Gujarat’s language, script and its temples are integral parts of its long and glorious history. The oldest written record of Gujarat's history is in a 2000-year-old Greek book titled 'The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean'. At this time, Gujarat had already long ago been a part of the Indus Valley Civilization. In fact, the famous and stunning Dwarkadhish Temple already existed at the time this book was written, before being reconstructed. One of the temples that add to the significance of Gujarat is the Somnath Temple. It is one of the revered 12 Jyotirlingas of Bhagwan Shiva. This temple has its own story of enduring centuries, undergoing reconstruction several times. The first form of the temple is so old that it is attributed to an unknown time in the past. The first acknowledged history of the temple dates to the second form of this temple was said to be built at the same site by the Yadava kings around 649 CE. Like many other temples in India and in Gujarat, this second form was destroyed in 725 CE by an Arab Governor, according to some disputed accounts. The temple was resuscitated in 815 CE by king Nagabhata II, who finally created it as a large structure of sandstone. -

Incredible Gujarat 06 Nights / 07 Days

Incredible Gujarat 06 Nights / 07 Days Tour Highlights: Highlights: Dwarka: 02 Nights Bet Dwarka Nageshvara Jyotirlinga Gopi Talab Rukmani Temple Gomati Ghats Sudama Setu Somnath: 01 Night Somnath Temple Kirti Mandir (on the way Porbandar) Diu: 01 Night Diu Fort Sent Paul Church Gangeshwar Temple Diu Beaches Rajkot: 01 Night Watson Museum Kaba Gandhi no delo Ramakrishna Ashram Vadodara: 01 Night Lakshmi Vilas Palace Maharaja Fateh Singh Museum Sur Sagar Lake Meal: 06 Breakfast & 06 Dinner Day Wise Itinerary: Day : 1 Ahmedabad – Jamnagar – Dwarka (Driving: Ahmedabad – Dwarka // Approx. 08 hrs // 453 kms). 1 / 5 Arrive at Ahmedabad, pick-up from Airport/Railway station or Hotel. Proceed to Dwarka En-route visit Lakhota Lake, Lakhota Museum and Bala Hanuman Temple known for its nonstop Ramdhun since 1956 and it mentioned in Guinness Book of World Records. later proceed to Dwarka. Dwarka is an ancient city in the north western Indian state of Gujarat. It’s known as a Hindu pilgrimage site. The ancient Dwarkadhish Temple has an elaborately tiered main shrine, a carved entrance and a black-marble idol of Lord Krishna. Dwarka Beach and nearby Dwarka Lighthouse offer views of the Arabian Sea. Southeast, Gaga Wildlife Sanctuary protects migratory birds and endangered species like the Indian wolf. Arrival Dwarka and check in Hotel. Evening free for leisure activities. In evening, enjoy Dinner at Hotel, Overnight stay at Dwarka. Meal: Breakfast & Dinner Day : 2 Dwarka - Bet Dwarka - Dwarka Early Morning enjoy Mangla Aarti Darshan. Later enjoy Breakfast at hotel. Later visit Bet Dwarka, believed to be the original abode of Lord Krishna. -

PILGRIM CENTRES of INDIA (This Is the Edited Reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the Same Theme Published in February 1974)

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA A DISTINCTIVE CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF INDIA (A Half-Yearly Publication) Vol.38 No.2, 76th Issue Founder-Editor : MANANEEYA EKNATHJI RANADE Editor : P.PARAMESWARAN PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA (This is the edited reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the same theme published in February 1974) EDITORIAL OFFICE : Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, 5, Singarachari Street, Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005. The Vivekananda Kendra Patrika is a half- Phone : (044) 28440042 E-mail : [email protected] yearly cultural magazine of Vivekananda Web : www.vkendra.org Kendra Prakashan Trust. It is an official organ SUBSCRIPTION RATES : of Vivekananda Kendra, an all-India service mission with “service to humanity” as its sole Single Copy : Rs.125/- motto. This publication is based on the same Annual : Rs.250/- non-profit spirit, and proceeds from its sales For 3 Years : Rs.600/- are wholly used towards the Kendra’s Life (10 Years) : Rs.2000/- charitable objectives. (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTION: Annual : $60 US DOLLAR Life (10 Years) : $600 US DOLLAR VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements 1 2. Editorial 3 3. The Temple on the Rock at the Land’s End 6 4. Shore Temple at the Land’s Tip 8 5. Suchindram 11 6. Rameswaram 13 7. The Hill of the Holy Beacon 16 8. Chidambaram Compiled by B.Radhakrishna Rao 19 9. Brihadishwara Temple at Tanjore B.Radhakrishna Rao 21 10. The Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry Prof. Manoj Das 24 11. Kaveri 30 12. Madurai-The Temple that Houses the Mother 32 13.