Private Force/Public Goods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological Weapons and “Bioterrorism” in the First Years of the 21St Century

ALERT: A previously posted version of this paper (dated April 16, 2002) was a draft that was NOT intended for distribution. If you downloaded this earlier version, please destroy your copy and refer to the revised version (updated April 3, 2003) given below. Biological Weapons and “Bioterrorism” in the First Years of the 21st Century Milton Leitenberg Center for International and Security Studies School of Public Affairs University of Maryland Paper prepared for Conference on “The Possible Use of Biological Weapons by Terrorists Groups: Scientific, Legal, and International Implications [ICGEB, Landau Network, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Italy] Rome, Italy April 16, 2002 Paper updated to April 3, 2003 Contents Page Introduction 1 Part I: The US Destruction of the Verification Protocol to the Biological Weapons Convention: July and November/ December 2001 2 Part II: September 11, 2001: The First Success in Mass Casualty Terrorism 21 Part III: Al Queda and Biological Agents or Weapons 26 Part IV: The Anthrax Events in the United States in the Fall of 2001 37 Part V: The Question of Offensive/Defensive Distinctions in Biological Weapons Research, and the Potential Stimulus to BW Proliferation By Expanded Research Programs 48 References and Notes 91 Biological Weapons and "Bioterrorism" in the First Years of the 21st Century INTRODUCTION In a sequence of recent papers I have reviewed the experience of biological weapons in the twentieth century,1 and presented an analysis of the degree of threat posed by these weapons in the period 1995 to 2000, in distinction to the portrayal of that threat, most particularly in the United States.2 The present paper describes the events of the last few years, which will determine much of what will occur in the near future. -

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards

2010 dateline SPECIAL EDITION CARACAS, VENEZUELA WINNERS OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS dateline 2010 1 LETTERFROM THE PRESIDENT t the Overseas Press Club of America, we are marching through our 71st year insisting that fact-based, hard-news reporting from abroad is more important than ever. As we salute the winners of our 20 awards, I am proud to say their work is a tribute to the public’s right to know. As new forms of communication erupt, the incessant drumbeat of the A24-hour news cycle threatens to overwhelm the public desire for information by swamping readers and viewers with instant mediocrity. Our brave winners – and IS PROUD the news organizations that support them – reject the temptation to oversimplify, trivialize and then abandon important events as old news. For them, and for the OPC, the earthquakes in Haiti and Chile, the shifting fronts in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, the drug wars of Mexico and genocides and commodity grabs in Africa need to be covered thoroughly and with integrity. TO SUPPORT The OPC believes quality journalism will create its own market. In spite of the decimation of the traditional news business, worthwhile journalism can and will survive. Creators of real news will get paid a living wage and the young who desire to quest for the truth will still find journalism viable as a proud profession and a civic good. We back that belief with our OPC Foundation, which awards 12 scholarships a year to deserving students who express their desire to become foreign correspondents while submitting essays on international subjects. -

The Interviews

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to April 2017 2017 Marcus du Soutay 4/10/17 Mark Zupan Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest 4/6/17 Johnathan Letham More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers 4/6/17 Ali Almossawi Bad Choices: How Algorithms Can Help You Think Smarter and Live Happier 4/5/17 Steven Vladick Prof. of Law at UT Austin 3/31/17 Nick Middleton An Atals of Countries that Don’t Exist 3/30/16 Hope Jahren Lab Girl 3/28/17 Mary Otto Theeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality and the Struggle for Oral Health 3/28/17 Lawrence Weschler Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists 3/28/17 Mark Olshaker Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs 3/24/17 Geoffrey Stone Sex and Constitution 3/24/17 Bill Hayes Insomniac City: New York, Oliver and Me 3/21/17 Basharat Peer A Question of Order: India, Turkey and the Return of the Strongmen 3/21/17 Cass Sunstein #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media 3/17/17 Glenn Frankel High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic 3/15/17 Sloman & Fernbach The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Think Alone 3/15/17 Subir Chowdhury The Difference: When Good Enough Isn’t Enough 3/14/17 Peter Moskowitz How To Kill A City: Gentrification, Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood 3/14/17 Bruce Cannon Gibney A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America 3/10/17 Pam Jenoff The Orphan's Tale: A Novel 3/10/17 L.A. -

A Responsible Exit Strategy

PORTER: IRAQ, EXIT STRATEGY THE THIRD OPTION IN IRAQ: A RESPONSIBLE EXIT STRATEGY Gareth Porter Dr. Porter is an independent historian and foreign-policy analyst who has published studies of negotiations to end wars in Vietnam, Cambodia and the Philippines. His latest book is Perils of Dominance: Imbalance of Power and the Road to War in Vietnam (University of California Press, 2005). he U.S. military occupation of moreover, is still resisted by a large major- Iraq is the subject of a political ity of the political elite. In the first clear stalemate at home, despite its test, on May 26, an amendment calling on Tlack of public support. A CNN/ President Bush to devise a plan for with- USA Today/Gallup Poll survey in mid-June drawal from Iraq was defeated in the showed that 59 percent said they opposed House of Representatives 300 to 128. “the U.S. war with Iraq,” while only 39 Thus Congress is far more supportive of a percent said they favored it. Even more long occupation than is the populace. This significant, the percentage opposing war has enabled the Bush administration to act with Iraq had increased by 21 points since as though it were immune to the polling mid-March. A Harris Poll taken in June data, declaring that it has a “victory revealed that 63 percent of the sample strategy” rather than an “exit strategy.” favored bringing “most of our troops home The wide gap between public opinion in the next year,” while only 33 percent and the split in Congress on Iraq is in large favored waiting until a “stable government” part the result of a failed national discourse had been established in Iraq. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

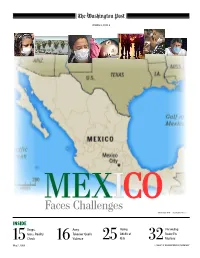

Faces Challengesico MAP by GENE THORP — the WASHINGTON POST

[ABCDE] VOLUME 8, Issue 9 MEXFaces ChallengesICO MAP BY GENE THORP — THE WASHINGTON POST INSIDE Drugs, Army Young Unraveling Guns, Reality Takeover Quells Adults at Swine Flu 15 Check 16 Violence 25 Risk 32 Mystery May 5, 2009 © 2009 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 8, Issue 9 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word About Mexico Faces Challenges Lessons: Mexico, a country with a rich Three times the size of Texas, Mexico is a country of cultural heritage and history, remains contrasts. From towering mountains to coastal lowlands, closely tied to the U.S. Lessons in tropics to deserts. A country of World Heritage sites economics, global health provisions and preserving a rich history and culture, and leaders in Mexico international policy are abundant as Mexico confronts the epidemics of drug City moving it into the 21st century. Ranked by the World trafficking, violence and the A/H1N1 virus. Bank as the twelfth largest economy in the world, it is For journalism teachers, the coverage of experiencing deep recession. these issues by The Post provides lessons in depth reporting and breaking news Mexico is a country of large cities of millions and dusty coverage. villages. It is a country of cathedrals, wayside shrines and devout respect for life facing drug cartels and violence. It Level: Mid to High is the latter that was the original focus of the May guide. Subjects: U.S. History, Journalism Following the meeting of presidents Obama and Calderón Related Activity: Economics, World in Mexico, Post photographers, writers and Foreign Service History, Health correspondents were covering the violence that has resulted from the flow of U.S.-made firearms south and drugs north of the shared border in a series called Mexico at War: On the Front Lines. -

Russell, James A. : Innovation in the Crucible of War: the United States

INNOVATION IN THE CRUCIBLE OF WAR: THE UNITED STATES COUNTERINSURGENCY CAMPAIGN IN IRAQ, 2005-2007 By James A. Russell War Studies Department King’s College, University of London Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD, July 2009 ABSTRACT This dissertation critically examines the conduct of counterinsurgency operations in Iraq by a series of U.S. Army and Marine Corps units operating in Anbar and Ninewa provinces in Iraq from late 2005 through early 2007. The popular narrative of the American counterinsurgency campaign in Iraq is that military success followed the ‘surge’ of American troops in the spring 2007 and the appointment of General David Petraeus as the ground commander committed to counterinsurgency operations. While both factors were undoubtedly important in America’s counterinsurgency campaign in Iraq, the research in this book demonstrates that this narrative is somewhat misleading. I argue that by the time Petraeus took over command to “rescue” the counterinsurgency campaign in early 2007, American military units had already built successful counterinsurgency competencies and were experiencing battlefield success – most dramatically in the battle for Ramadi in the fall of 2006. The process of successful adaptation in the field began in late 2005 in Anbar and Ninewa provinces and did so with little direction from higher military and civilian authorities. I argue that that the collective momentum of tactical adaptation within the units studied here can be characterized as organizational innovation. I define innovation as the widespread development of new organizational capacities not initially present in these units when they arrived in Iraq and which had only tangential grounding in previous military doctrine. -

Bloomberg News Expose of Kushner Real Estate Holdings Wins Gold Keyboard in 2018 New York Press Club Journalism Awards

NEWS FROM THE NEW YORK PRESS CLUB www.nypressclub.org | @NYPressClub contact: Debra Caruso, DJC Communications 212.971.9708 [email protected] BLOOMBERG NEWS EXPOSE OF KUSHNER REAL ESTATE HOLDINGS WINS GOLD KEYBOARD IN 2018 NEW YORK PRESS CLUB JOURNALISM AWARDS "Unmasking the Kushner Real Estate Empire" by Bloomberg News is the grand-prize winner of the New York Press Club's 2018 Gold Keyboard. The NYPC's highest award singles out a pair of reporters who peeled back the layers to reveal real estate deals involving the Kushner family that stretched across the world and into the White House and that are now the subject of federal investigations. An additional 76 winners in 29 categories were selected from almost 500 entries submitted by TV, radio, newspapers, websites, magazines and newswires in New York City and around the U.S. Awards will be presented at the Club’s annual dinner, Monday, June 4, 2018 at The Water Club in Manhattan, 7 p.m. A special note this year: Washington Post editor-in-chief Martin Baron will receive the NYPC’s first non-contested award. The “Gabe Pressman Truth to Power Award” recognizes our friend, colleague and paragon – WNBC’s Gabe Pressman, who died last June – for his seven decades of reporting news and defending the First Amendment and media freedoms. “Marty Baron and Gabe Pressman are from different journalism eras but both share an indisputable passion for our craft and an unquenchable drive to present the truth and challenge corrupt power,” said NY Press Club president Steve Scott. Scott added that the high number of entries across all news media platforms attests to the continued good health of journalism despite challenges from some about the accuracy and legitimacy of professional journalists. -

JFQ 47 Chinese Sailors Man the Rails As Download As Computer Wallpaper at Ndupress.Ndu.Edu Qingdoa Enters Pearl Harbor

4 pi J O I N T F O R C E Q uarterly Issue 47, 4th Quarter 2007 New Books from NDU Press Published for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff by National Defense University JFQ Congress At War: coming next in... The Politics of Conflict Since 1789 by Charles A. Stevenson Homeland Defense Reviews the historical record of the U.S. Congress in authorizing, funding, overseeing, and terminating major military operations. Refuting arguments that Congress cannot and should not set limits or conditions on the use of the U.S. Armed Forces, this book catalogs the many times when previous Congresses have enacted restrictions—often with the acceptance and compliance of wartime Presidents. While Congress has formally declared war only 5 U.S. Northern Command times in U.S. history, it has authorized the use of force 15 other times. In recent decades, however, lawmakers have weakened their Constitutional claims by failing on several occasions to enact measures either supporting or opposing military operations ordered by the President. plus Dr. Charles A. Stevenson teaches at the Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins Uni- versity. A former professor at the National War College, he also draws upon his two decades as a Senate staffer Download as computer wallpaper at ndupress.ndu.edu on national security matters to illustrate the political motivations that influence decisions on war and peace Defense Support of Concise, dramatically written, and illustrated with summary tables, this book is a must-read for anyone inter- Civil Authorities ested in America’s wars—past or present. -

Fair Or Foul? Ethics and Sportsjournalism

the uw-madison center for journalism ethics presents fair or foul? ethics and sportsjournalism 2015 conference Featuring speakers from ESPN, NBC Sports, CBS News, the NFL, and many other media outlets april 10, 2015 union south The Center for Journalism Ethics Schedule of Events Welcome to a day that promises Advisory 8:30 Breakfast/registration to be filled with thought-pro- Board voking discussion of some of 8:50 Opening remarks, Robert Drechsel and Kathleen Culver the most significant issues ever Tom Bier to face journalism and govern- Kathy Bissen 9:00 Keynote by Eric Lichtblau, New York Times ment: Who has what obligations Media Minefields: Journalism, National Security and the Right to Know James E. Burgess to whom in most appropriately 10:15 Break resolving conflicts between the Scott Cohn public’s need for both informa- Rick Fetherston 10:30 Protecting Sources and Data in a Surveillance Environment tion and privacy in a self-gov- Peter D. Fox Moderator: Jason Shepard, Cal State-Fullerton erning society and the need to Welcome Lewis Friedland Brant Houston, University of Illinois protect citizens and the state from Robert E. Drechsel Martin Kaiser Jonathan Stray, Associated Press from serious harm? James E. Burgess Jeff Mayers Marisa Taylor, McClatchey DC Chair in Journalism Ethics Journalists find themselves Jack Mitchell 11:30 Anthony Shadid Award for Journalism Ethics, presented by Jack Mitchell at the center of the debate John Smalley to the Associated Press, Matt Apuzzo, Ted Bridis and Adam Goldman in many ways. They provide a Carol Toussaint 12:00 Lunch critical conduit for information the public and sometimes the Owen Ullmann government itself need to develop and deploy sound policy. -

View of War 33 Sweeney, Ernest Moniz, Daniel Schrag, Michael Greenstone, Jon Thomas G

Dædalus coming up in Dædalus: Protecting the Internet David Clark, Vinton G. Cerf, Kay Lehman Schlozman, Sidney Verba as a Public Commons & Henry E. Brady, R. Kelly Garrett & Paul Resnick, L. Jean Camp, Dædalus Deirdre Mulligan & Fred B. Schneider, John B. Horrigan, Lee Sproull, Helen Nissenbaum, Coye Cheshire, and others Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Summer 2011 The American Denis Donoghue, Rolena Adorno, Gish Jen, E. L. Doctorow, David Narratives Levering Lewis, Jay Parini, Michael Wood, William Chafe, Philip Summer 2011: The Modern American Military Fisher, Craig Calhoun, Larry Tribe, Peter Brooks, David A. Hollinger, William Ferris, Linda Kerber, and others The William J. Perry Foreword 5 Modern David M. Kennedy Introduction 10 American The Alternative Robert Fri, Stephen Ansolabehere, Steven Koonin, Michael Graetz, Military Lawrence Freedman The Counterrevolution in Strategic Affairs 16 Energy Future Pamela Matson & Rosina Bierbaum, Mohamed El Ashry, James Brian McAllister Linn The U.S. Armed Forces’ View of War 33 Sweeney, Ernest Moniz, Daniel Schrag, Michael Greenstone, Jon Thomas G. Mahnken Weapons: The Growth & Spread Krosnick, Naomi Oreskes, Kelly Sims Gallagher, Thomas Dietz, of the Precision-Strike Regime 45 Paul Stern & Elke Weber, Roger Kasperson & Bonnie Ram, Robert Robert L. Goldich American Military Culture Stavins, Michael Dworkin, Holly Doremus & Michael Hanemann, from Colony to Empire 58 Ann Carlson, Robert Keohane & David Victor, and others Lawrence J. Korb Manning & Financing the Twenty-First- & David R. Segal Century All-Volunteer Force 75 plus Public Opinion, The Common Good, Immigration & the Future Deborah D. Avant Military Contractors & of America &c. & Renée de Nevers the American Way of War 88 Jay M. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography Or Autobiography Year Winner 1917

A Monthly Newsletter of Ibadan Book Club – December Edition www.ibadanbookclub.webs.com, www.ibadanbookclub.wordpress.com E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography or Autobiography Year Winner 1917 Julia Ward Howe, Laura E. Richards and Maude Howe Elliott assisted by Florence Howe Hall 1918 Benjamin Franklin, Self-Revealed, William Cabell Bruce 1919 The Education of Henry Adams, Henry Adams 1920 The Life of John Marshall, Albert J. Beveridge 1921 The Americanization of Edward Bok, Edward Bok 1922 A Daughter of the Middle Border, Hamlin Garland 1923 The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1924 From Immigrant to Inventor, Michael Idvorsky Pupin 1925 Barrett Wendell and His Letters, M.A. DeWolfe Howe 1926 The Life of Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing 1927 Whitman, Emory Holloway 1928 The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas, Charles Edward Russell 1929 The Training of an American: The Earlier Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1930 The Raven, Marquis James 1931 Charles W. Eliot, Henry James 1932 Theodore Roosevelt, Henry F. Pringle 1933 Grover Cleveland, Allan Nevins 1934 John Hay, Tyler Dennett 1935 R.E. Lee, Douglas S. Freeman 1936 The Thought and Character of William James, Ralph Barton Perry 1937 Hamilton Fish, Allan Nevins 1938 Pedlar's Progress, Odell Shepard, Andrew Jackson, Marquis James 1939 Benjamin Franklin, Carl Van Doren 1940 Woodrow Wilson, Life and Letters, Vol. VII and VIII, Ray Stannard Baker 1941 Jonathan Edwards, Ola Elizabeth Winslow 1942 Crusader in Crinoline, Forrest Wilson 1943 Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Samuel Eliot Morison 1944 The American Leonardo: The Life of Samuel F.B.