18 Sports & New Orleans Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor David Ake, University of Miami Associate Professor Stephen Berrey Associate Professor Christi-Anne Castro Associate Professor Mark Clague © Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik 2016 DEDICATION To Jarvis P. Chuckles, an amalgamation of all those who made this project possible. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation was made possible by fellowship support conferred by the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School and the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities, as well as ample teaching opportunities provided by the Musicology Department and the Residential College. I am also grateful to my department, Rackham, the Institute, and the UM Sweetland Writing Center for supporting my work through various travel, research, and writing grants. This additional support financed much of the archival research for this project, provided for several national and international conference presentations, and allowed me to participate in the 2015 Rackham/Sweetland Writing Center Summer Dissertation Writing Institute. I also remain indebted to all those who helped me reach this point, including my supervisors at the Hatcher Graduate Library, the Music Library, the Children’s Center, and the Music of the United States of America Critical Edition Series. I thank them for their patience, assistance, and support at a critical moment in my graduate career. This project could not have been completed without the assistance of Bruce Boyd Raeburn and his staff at Tulane University’s William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive of New Orleans Jazz, and the staff of the Historic New Orleans Collection. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

In 191^B Played His First Professional Job. He Bought a Sax on August 3/ and Played His First Job on September 3

PAUL BARNES 1 Reel I [of 2]--Digest-Retype June 16, 1969 Also present; Barry Martyn, Lars Edegran/ Richard B. Alien Paul Daniel Barnes, whose professional name is "Polo" Barnes/ was born November 22, 1903., in New Orleans/ Louisiana. When he was six years old, he started playing a ten cent [tin] fife. This kind of fife was popular in New Orleans. George Lewis, [Emil-e] Barnes and Sidney ^. Bechet and many others also started on the fife. In 191^B played his first professional job. He bought a sax on August 3/ and played his first job on September 3. He had a foundation from playing the fife. As a kid, he played Emile Barnes' clarinet. There were few Boehm system clarinetists then. 'PB now plays a Boehm. Around 1920 PB started playing a Boehm system clarinet, but he couldn't get the hang of it/ so he went back to the sax/ which he played until he got with big bands. He took solos on the soprano sax [and later alto sax], but not on the clarinet. He is largely self-taught. He tooT< three or four saxophone lessons from Lorenzo Tie [Jr.]. Tio was always high. PB learned clarinet from Emile Barnes. PB wanted to play like Sidney Bechet, but he couldn't get the tone. PB played tenor sax around New York/ baritone sa^( [and still occasionally alto]. [Today PB is still playing clarinet almost exclusively--RBA, June 7, 1971<] His first organized band was PB's and Lawrence Marrero's Original Diamond Orchestra. It had Bush Hall, tp/ replaced by Red Alien; Cie Frazier [d]; Lawrence [Marrero] / [bj?]. -

Whicl-I Band-Probably Sam; Cf

A VERY "KID" HOWARD SUMMARY Reel I--refcyped December 22, 1958 Interviewer: William Russell Also present: Howard's mother, Howard's daughter, parakeets Howard was born April 22, 1908, on Bourbon Street, now renamed Pauger Street. His motTier, Mary Eliza Howard, named him Avery, after his father w'ho di^d in 1944* She sang in church choir/ but not professionally. She says Kid used to beat drum on a box with sticks, when he was about twelve years old. When he was sixteen/ he was a drummer. They lived at 922 St. Philip Street When Kid was young. He has lived around tliere all of his life . Kid's father didn't play a regular instrument, but he used to play on^ a comb, "make-like a. trombone," and he used to dance. Howard's parents went to dances and Tiis mother remembers hearing Sam Morgan's band when she was young, and Manuel Perez and [John] Robichaux . The earliest band Kid remembers is Sam Morgan's. After Sam died, he joined the Morgan band/ witli Isaiah Morgan. He played second trumpet. Then he had his own band » The first instrument he.started on was drums . Before his first marriage, when he got his first drums/ he didn't know how to put them up. He had boughtfhem at Werlein's. He and his first wife had a time trying to put them together * Story about }iis first attempt at the drums (see S . B» Charters): Sam Morgan had the original Sam Morgan Band; Isaiah Morgan had l:J^^i', the Young Morgan Band. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Charlie Christian

Prof. Jeff Campbell Trevor de Clercq 03/05/07 CHARLIE CHRISTIAN CHRONOLOGICAL BIOGRAPHY (based on Broadbent 2003) July 29, 1916: Charlie Christian (hereafter CC) born in Bonham, TX Father is a compressor operator in cotton mill; Mother is a hotel maid c.1918 (age 2): Father loses eyesight; Family moves to Oklahoma City, OK; Father works as a busker on the streets of the city as a guitar player 1926 (age 10): Father dies; CC inherits his father's two guitars 1928 (age 12): CC begins high school; Takes classes with Zelia N. Breaux Oil discovered in Oklahoma City 1930's (teenager): Oklahoma City is a major stopover for bands traveling east and west Deep Deuce area of Oklahoma City becomes a popular jazz neighborhood Older brother Edward becomes an established band leader Western Swing bands feature electric guitar with single-note solos 1932 (age 16): CC meets and jams with Lester Young 1933 (age 17): T-Bone Walker returns to Oklahoma City and jams with CC CC takes bass lessons with Chuck Hamilton 1934 (age 18): CC amplifies his acoustic guitar during gigs with brother Edward 1935 (age 19): CC jams with Cootie Williams as Duke Ellington comes through town CC has a regular gig with Leslie Sheffield and the Rhythmaires 1936 (age 20): CC begins touring the Plains States with various ensembles 1937 (age 21): CC acquires his first electric guitar and amp (Gibson ES150) 1938 (age 22): First recordings of jazz on an electric guitar are made Charlie Parker sees CC play in Kansas City 1939 (age 23): CC returns to Oklahoma City and fronts his own small group Benny Goodman begins recording with various electric guitarists Benny Goodman offers guitar-player Floyd Smith a contract, which is turned down by Smith's manager John Hammond, Goodman's manager, offers CC the job Aug. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Newsletternewsletter March 2015

NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER MARCH 2015 HOWARD ALDEN DIGITAL RELEASES NOT CURRENTLY AVAILABLE ON CD PCD-7053-DR PCD-7155-DR PCD-7025-DR BILL WATROUS BILL WATROUS DON FRIEDMAN CORONARY TROMBOSSA! ROARING BACK INTO JAZZ DANCING NEW YORK ACD-345-DR BCD-121-DR BCD-102-DR CASSANDRA WILSON ARMAND HUG & HIS JOHNNY WIGGS MOONGLOW NEW ORLEANS DIXIELANDERS PCD-7159-DR ACD-346-DR DANNY STILES & BILL WATROUS CLIFFF “UKELELE IKE” EDWARDS IN TANDEM INTO THE ’80s HOME ON THE RANGE AVAilable ON AMAZON, iTUNES, SPOTIFY... GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION 1206 Decatur Street New Orleans, LA 70116 phone: (504) 525-5000 fax: (504) 525-1776 email: [email protected] website: jazzology.com office manager: Lars Edegran assistant: Jamie Wight office hours: Mon-Fri 11am – 5pm entrance: 61 French Market Place newsletter editor: Paige VanVorst contributors: Jon Pult and Trevor Richards HOW TO ORDER Costs – U.S. and Foreign MEMBERSHIP If you wish to become a member of the Collector’s Record Club, please mail a check in the amount of $5.00 payable to the GHB JAZZ FOUNDATION. You will then receive your membership card by return mail or with your order. As a member of the Collector’s Club you will regularly receive our Jazzology Newsletter. Also you will be able to buy our products at a discounted price – CDs for $13.00, DVDs $24.95 and books $34.95. Membership continues as long as you order one selection per year. NON-MEMBERS For non-members our prices are – CDs $15.98, DVDs $29.95 and books $39.95. MAILING AND POSTAGE CHARGES DOMESTIC There is a flat rate of $3.00 regardless of the number of items ordered. -

'Slow Drag' Pavageau

NEWSLETTER OCT-2016 ologyology Alcide ‘Slow Drag’ Pavageau G.H.B. JAZZ FOUNDATION • JAZZOLOGY RECORDS GEORGE H. BUCK JAZZ FOUNDATION 1206 DECATUR STREET • NEW ORLEANS, LA 70116 Phone: +1 (504) 525-5000 Office Manager: Lars Edegran Fax: +1 (504) 525-1776 Assistant: Mike Robeson Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon-Fri 11am – 5pm Website: www.jazzology.com Entrance: 61 French Market Place Newsletter Editor: Paige VanVorst Contributors: Lars Edegran, Mike Layout & Design: David Stocker Robeson, David Stocker HOW TO ORDER COSTS – U.S. AND FOREIGN MEMBERSHIP If you wish to become a member of the Collector’s Record Club, please mail a check in the amount of $5.00 payable to the GHB Jazz Foundation. You will then receive your membership card by return mail or with your order. *Membership continues as long as you order at least one selection per year. You will also be able to buy our products at a special discounted price: CDs for $13.00 DVDs for $20.00 Books for $25.00 NON-MEMBERS For non-members our prices are: CDs for $15.98 DVDs for $25.00 Books for $30.00 DOMESTIC MAILING & POSTAGE CHARGES There is a flat rate of $3.00 regardless of the number of items ordered. OVERSEAS SHIPPING CHARGES 1 CD $13.00; 2-3 CDS $15.00; 4-6 CDS $20.00; 7-10 CDS $26.00 Canadian shipping charges are 50% of overseas charges ALL PAYMENTS FOR FOREIGN ORDERS MUST BE MADE WITH EITHER: • INTERNATIONAL MONEY ORDER • CHECK DRAWN IN U.S. DOLLARS FROM A U.S. -

New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation

New Orleans' Welcome to Jazz country, where Maison Blanche our heartbeat is a down beat and salutes the the sounds of music fill the air . Welcome to Maison Blanche coun• New Orleans Jazz try, where you are the one who calls the tune and fashion is our and Heritage daily fare. Festival 70 maison blanche NEW ORLEANS Schedule WEDNESDAY - APRIL 22 8 p.m. Mississippi River Jazz Cruise on the Steamer President. Pete Fountain and his Orchestra; Clyde Kerr and his Orchestra THURSDAY - APRIL 23 12:00 Noon Eureka Brass Band 12:20 p.m. New Orleans Potpourri—Harry Souchon, M.C. Armand Hug, Raymond Burke, Sherwood Mangiapane, George Finola, Dick Johnson Last Straws 3:00 p.m. The Musical World of French Louisiana- Dick Allen and Revon Reed, M. C.'s Adam Landreneau, Cyprien Landreneau, Savy Augustine, Sady Courville, Jerry Deville, Bois Sec and sons, Ambrose Thibodaux. Clifton Chenier's Band The Creole Jazz Band with Dede Pierce, Homer Eugene, Cie Frazier, Albert Walters, Eddie Dawson, Cornbread Thomas. Creole Fiesta Association singers and dancers. At the same time outside in Beauregard Square—for the same $3 admission price— you'll have the opportunity to explore a variety of muical experiences, folklore exhibits, the art of New Orleans and the great food of South Louisiana. There will be four stages of music: Blues, Cajun, Gospel and Street. The following artists will appear throughout the Festival at various times on the stages: Blues Stage—Fird "Snooks" Eaglin, Clancy "Blues Boy" Lewis, Percy Randolph, Smilin Joe, Roosevelt Sykes, Willie B. Thomas, and others. -

Checklist by Room

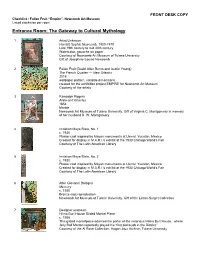

FRONT DESK COPY Checklist - Fallen Fruit “Empire”, NewcomB Art Museum Listed clockwise per room Entrance Room: The Gateway to Cultural Mythology 1 Artist Unknown Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870 Late 19th century to mid 20th century Watercolor, gouache on paper Courtesy of Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Gift of Josephine Louise Newcomb 2 Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young) The French Quarter — New Orleans 2018 wallpaper pattern, variable dimensions created for the exhibition project EMPIRE for Newcomb Art Museum Courtesy of the artists 3 Randolph Rogers Atala and Chactas 1854 Marble Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of Virginia C. Montgomery in memory of her husband R. W. Montgomery 4 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 1 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 5 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 2 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 6 After Giovanni Bologna Mercury c. 1580 Bronze cast reproduction Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of the Linton-Surget Collection 7 Designer unknown Hilma Burt House Gilded Mantel Piece c. 1906 This gilded mantelpiece adorned the parlor of the notorious Hilma Burt House, where Jelly Roll Morton reportedly played his “first piano job in the District.” Courtesy of the Al Rose Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University 8 Casting by the Middle American Research Institute Cast inspired by architecture of the Governor’s Place of Uxmal, Yucatán, México c.1932 Plaster, created for A Century oF Progress Exposition (also known as The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933), M.A.R.I.