A Future for Traditional Values? Will Rock Climbing Degenerate Into 'Theme Park Exercise'?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mcofs Climbing Wall Specifications

THE MOUNTAINEERING COUNCIL OF SCOTLAND The Old Granary West Mill Street Perth PH1 5QP Tel: 01738 493 942 Website: www.mcofs.org.uk SCOTTISH CLIMBING WALLS: Appendix 3 Climbing Wall Facilities: Specifications 1. Climbing Wall Definitions 1.1 Type of Wall The MCofS recognises the need to develop the following types of climbing wall structure in Scotland. These can be combined together at a suitably sized site or developed as separate facilities (e.g. a dedicated bouldering venue). All walls should ideally be situated in a dedicated space or room so as not to clash with other sporting activities. They require unlimited access throughout the day / week (weekends and evenings till late are the most heavily used times). It is recommended that the type of wall design is specific to the requirements and that it is not possible to utilise one wall for all climbing disciplines (e.g. a lead wall cannot be used simultaneously for bouldering). For details of the design, development and management of walls the MCofS supports the recommendations in the “Climbing Walls Manual” (3rd Edition, 2008). 1.1.1. Bouldering walls General training walls with a duel function of allowing for the pursuit of physical excellence, as well as offering a relatively safe ‘solo’ climbing experience which is fun and perfect for a grass-roots introduction to climbing. There are two styles: indoor venues and outdoor venues to cater for the general public as a park or playground facility (Boulder Parks). Dedicated bouldering venues are particularly successful in urban areas* where local access to natural crags offering this style of climbing is not available. -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Gear Brands List & Lexicon

Gear Brands List & Lexicon Mountain climbing is an equipment intensive activity. Having good equipment in the mountains increases safety and your comfort level and therefore your chance of having a successful climb. Alpine Ascents does not sell equipment nor do we receive any outside incentive to recommend a particular brand name over another. Our recommendations are based on quality, experience and performance with your best interest in mind. This lexicon represents years of in-field knowledge and experience by a multitude of guides, teachers and climbers. We have found that by being well-equipped on climbs and expeditions our climbers are able to succeed in conditions that force other teams back. No matter which trip you are considering you can trust the gear selection has been carefully thought out to every last detail. People new to the sport often find gear purchasing a daunting chore. We recommend you examine our suggested brands closely to assist in your purchasing decisions and consider renting gear whenever possible. Begin preparing for your trip as far in advance as possible so that you may find sale items. As always we highly recommend consulting our staff of experts prior to making major equipment purchases. A Word on Layering One of the most frequently asked questions regarding outdoor equipment relates to clothing, specifically (and most importantly for safety and comfort), proper layering. There are Four basic layers you will need on most of our trips, including our Mount Rainier programs. They are illustrated below: Underwear -

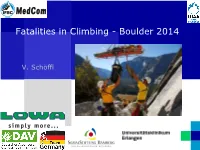

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014 V. Schöffl Evaluation of Injury and Fatality Risk in Rock and Ice Climbing: 2 One Move too Many Climbing: Injury Risk Study Type of climbing (geographical location) Injury rate (per 1000h) Injury severity (Bowie, Hunt et al. 1988) Traditional climbing, bouldering; some rock walls 100m high 37.5 a Majority of minor severity using (Yosemite Valley, CA, USA) ISS score <13; 5% ISS 13-75 (Schussmann, Lutz et al. Mountaineering and traditional climbing (Grand Tetons, WY, 0.56 for injuries; 013 for fatalities; 23% of the injuries were fatal 1990) USA) incidence 5.6 injuries/10000 h of (NACA 7) b mountaineering (Schöffl and Winkelmann Indoor climbing walls (Germany) 0.079 3 NACA 2; 1999) 1 NACA 3 (Wright, Royle et al. 2001) Overuse injuries in indoor climbing at World Championship NS NACA 1-2 b (Schöffl and Küpper 2006) Indoor competition climbing, World championships 3.1 16 NACA 1; 1 NACA 2 1 NACA 3 No fatality (Gerdes, Hafner et al. 2006) Rock climbing NS NS 20% no injury; 60% NACA I; 20% >NACA I b (Schöffl, Schöffl et al. 2009) Ice climbing (international) 4.07 for NACA I-III 2.87/1000h NACA I, 1.2/1000h NACA II & III None > NACA III (Nelson and McKenzie 2009) Rock climbing injuries, indoor and outdoor (NS) Measures of participation and frequency of Mostly NACA I-IIb, 11.3% exposure to rock climbing are not hospitalization specified (Backe S 2009) Indoor and outdoor climbing activities 4.2 (overuse syndromes accounting for NS 93% of injuries) Neuhhof / Schöffl (2011) Acute Sport Climbing injuries (Europe) 0.2 Mostly minor severity Schöffl et al. -

2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook

Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook Allison Swanson [Basic Course Chair] Cebe Wallace [Meet and Greet, Reunion] Diane Gaddis [SIG Organization] Glenn Eades [Graduation] Jan Abendroth [Field Trips] Jeneca Bowe [Lectures] Jared Bowe [Student Tracking] Jim Nelson [Alpine Fashionista, North Cascades Connoisseur] Liana Robertshaw [Basic Climbs] Vineeth Madhusudanan [Enrollment] Fred Beckey, photograph in High Adventure, by Ira Spring, 1951 In loving memory Fred Page Beckey 1 [January 14, 1923 – October 30, 2017] Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 BASIC ALPINE CLIMBING COURSE STUDENT HANDBOOK COURSE OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ 3 Class Meetings ............................................................................................................................ 3 Field Trips ................................................................................................................................... 4 Small Instructional Group (SIG) ................................................................................................. 5 Skills Practice Nights .................................................................................................................. 5 References ................................................................................................................................... 6 Three additional -

Risk Assessment – Climbing Wall / Abseiling Version 3 Completed by TW Last Updated March 2019

Risk Assessment – Climbing Wall / Abseiling Version 3 Completed By TW Last Updated March 2019 Risk assessment 1-5 Participant Staff Likely to Degree of Likely to Degree of Area of Potential Risk occur injury likely occur injury likely How the risk can be minimised 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 45 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 Fall From Height 1. Clients will never be left unattended and 1. Clients trying out the wall and climbing 1 4 0 0 Instructor to include this in their initial above 6 foot without any PPE activity briefing. 2. Instructor to go through full training and be signed off by Manager or Assistant 2. Climbing the wall while being clipped in 1 5 2 5 Manager. Instructors always double checks incorrectly attachment point prior to the climber assending the wall 3. Climber could accidently unclip while 1 4 0 0 3. Use apposing carabiners climbing 4. Staff will be trained on correct fitting of 4. PPE set up incorrectly 2 5 0 0 PPE and have periodic spot checks 5. Visual PPE check to be carried out prior to 5. Failing of PPE equipment 2 5 0 0 every use and full PPE check carried out every 6 months by qualified personel 6. Incorrect belay procedure - client belaying 6. 2 clients belaying one climber - Only 2 4 0 0 on their own instructor to lower on belay only Falling Objects 1. All personal items to be taken out of 1. Personal Items falling from climber 3 2 3 2 pockets prior to starting activities 2. -

Jan 3 1 2014 Director of Athletics Instruction 11100

DIRATHINST 11100 . SA JAN 3 1 2014 DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS INSTRUCTION 11100 . SA Subj : ADMINISTRATION AND POLICIES OF CLIMBING WALL Encl: (1) Climbing Wall Belay Certification Requirements (2) Climbing Wall Watch Certification Requirements (3) CLIMBING Wall Watch Standard Operating Procedures Ref: (a) COMTMIDNINST 1601.lOJ Bancroft Hall Watch Instruction 1 . Purpose. To establish procedures and responsibilities regarding the administration of the Climbing Wall at the United States Naval Academy. 2. Cancellation. DIRATHINST 11100 . 5. 3. Background . The physical mission of the Naval Academy is to develop in Midshipmen the applied knowledge of wellness, lifetime physical fitness, athletic skills, and competitive spirit so as to endure physical hardship associated with military leadership and to instruct others in physical fitness and wellness. As part of this mission, the Naval Academy has added an artificial rock climbing wall, which will provide high quality and challenging physical education to its students. A thorough understanding by all faculty members and Midshipmen of their responsibility is necessary. 4. General Policies . a . Authorized Use of the Climbing Wall and Required Qualification: (1) The climbing Wall will be open to belay qualified Midshipmen and PE button holders during the DIRATHINST 11100.SA JAN 3 1 2014 following hours, except during periods of military drill, holidays (as promulgated by the PE Department) , and academic final exam periods: (a ) Monday-Friday: 1600-1800 (b) Saturday: 0800-1200 (2) Belay-qualified button holders will be permitted use of the wall only during established weekday lunch hour and evening climbing hours. Only belay-qualified Staff, Faculty, and their dependents over the age of 16 may climb during these periods. -

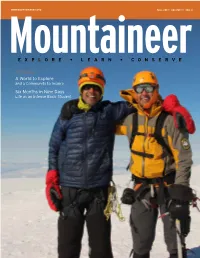

A World to Explore Six Months in Nine Days E X P L O R E • L E a R N

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG FALL 2017 • VOLUME 111 • NO. 4 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE in this issue: A World to Explore and a Community to Inspire Six Months in Nine Days Life as an Intense Basic Student tableofcontents Fall 2017 » Volume 111 » Number 4 Features The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy 26 A World to Explore the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. and a Community to Inspire 32 Six Months in Nine Days Life as an Intense Basic Student Columns 7 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Craig Romano 8 BOARD ELECTIONS 2017 10 PEAK FITNESS Preventing Stiffness 16 11 MOUNTAIN LOVE Damien Scott and Dandelion Dilluvio-Scott 12 VOICES HEARD Urban Speed Hiking 14 BOOKMARKS Freedom 9: By Climbers, For Climbers 16 TRAIL TALK It's The People You Meet Along The Way 18 CONSERVATION CURRENTS 26 Senator Ranker Talks Public Lands 20 OUTSIDE INSIGHT Risk Assessment with Josh Cole 38 PHOTO CONTEST 2018 Winner 40 NATURES WAY Seabirds Abound in Puget Sound 42 RETRO REWIND Governor Evans and the Alpine Lakes Wilderness 44 GLOBAL ADVENTURES An Unexpected Adventure 54 LAST WORD Endurance 32 Discover The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the Mountaineer uses: Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of CLEAR informational meetings at each of our seven branches. on the cover: Sandeep Nain and Imran Rahman on the summit of Mount Rainier as part of an Asha for Education charity climb. -

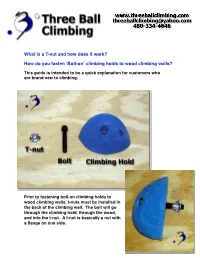

What Is a T-Nut and How Does It Work? How Do You Fasten ʻbolt-Onʼ

What is a T-nut and how does it work? How do you fasten ʻBolt-onʼ climbing holds to wood climbing walls? This guide is intended to be a quick explanation for customers who are brand new to climbing. Prior to fastening bolt-on climbing holds to wood climbing walls, t-nuts must be installed in the back of the climbing wall. The bolt will go through the climbing hold, through the wood, and into the t-nut. A t-nut is basically a nut with a flange on one side. The barrel of the t-nut can fit into a 7/16” hole, but the flange is 1” wide so it cannot fit through the hole. The flange catches the surface of the climbing wall surrounding the 7/16” hole. The Barrel of the T-nut should be recessed behind the front surface of the climbing wall by at least 1/ 4”. Climbing holds must not make di- rect contact with the t-nut. If the climbing hold makes direct con- tact with the t-nut it will eliminate the friction between the surface of the climbing wall and the back of the climbing hold. Climbing holds must have good contact with the climbing wall in order to be secure. Selecting the proper length bolts: Every climbing hold has a different shape and structure. Because of these variations, the depth of the bolt hole varies from one climbing hold to another. Frogs 20 Pack Example: The 20 pack of Frogs Jugs to the right consists of several different shaped grips. -

OUTDOOR ROCK CLIMBING INTENSIVE INTRODUCTION Boulder, CO EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST

www.alpineinstitute.com [email protected] Equipment Shop: 360-671-1570 Administrative Office: 360-671-1505 The Spirit of Alpinism OUTDOOR ROCK CLIMBING INTENSIVE INTRODUCTION Boulder, CO EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST This equipment list is aimed to help you bring only the essential gear for your mountain adventures. Please read this list thoroughly, but exercise common sense when packing for your trip. Climbs in the summer simply do not require as much clothing as those done in the fall or spring. Please pack accordingly and ask questions if you are uncertain. CLIMATE: Temperatures and weather conditions in Boulder area are often conducive to great climbing conditions. Thunderstorms, however, are somewhat common and intense rainstorms often last a few hours in the afternoons. Daytime highs range anywhere from 50°F to 80°F. GEAR PREPARATION: Please take the time to carefully prepare and understand your equipment. If possible, it is best to use it in the field beforehand. Take the time to properly label and identify all personal gear items. Many items that climbers bring are almost identical. Your name on a garment tag or a piece of colored electrical tape is an easy way to label your gear; fingernail polish on hard goods is excellent. If using tape or colored markers, make sure your labeling method is durable and water resistant. ASSISTANCE: At AAI we take equipment and its selection seriously. Our Equipment Services department is expertly staffed by climbers, skiers and guides. Additionally, we only carry products in our store have been thoroughly field tested and approved by our guides. This intensive process ensures that all equipment that you purchase from AAI is best suited to your course and future mountain adventures. -

White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015

RUMNEY ROCKS CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015 Introduction The Rumney Rocks Climbing Area encompasses approximately 150 acres on the south-facing slopes of Rattlesnake Mountain on the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) in Rumney, New Hampshire. Scattered across these slopes are approximately 28 rock faces known by the climbing community as "crags." Rumney Rocks is a nationally renowned sport climbing area with a long and rich climbing history dating back to the 1960s. This unique area provides climbing opportunities for those new to the sport as well as for some of the best sport climbers in the country. The consistent and substantial involvement of the climbing community in protection and management of this area is a testament to the value and importance of Rumney Rocks. This area has seen a dramatic increase in use in the last twenty years; there were 48 published climbing routes at Rumney Rocks in Ed Webster's 1987 guidebook Rock Climbs in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and are over 480 documented routes today. In 2014 an estimated 646 routes, 230 boulder problems and numerous ice routes have been documented at Rumney. The White Mountain National Forest Management Plan states that when climbing issues are "no longer effectively addressed" by application of Forest Plan standards and guidelines, "site specific climbing management plans should be developed." To address the issues and concerns regarding increased use in this area, the Forest Service developed the Rumney Rocks Climbing Management Plan (CMP) in 2008. Not only was this the first CMP on the White Mountain National Forest, it was the first standalone CMP for the US Forest Service.