Changes in the Mode of Labour Due to Shift in the Land Use Pattern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015-16 Term Loan

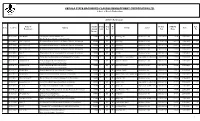

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF SEPTEMBER 2018 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 4172 026688 CHANGANACHERRY INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 182 1 1 0 -43 -41 141 4172 026701 KOTTAYAM INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 35 2 0 0 0 2 37 4172 026709 MAVELIKARA INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 36 1 0 0 0 1 37 4172 026716 PANDALAM INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 39 0 0 0 0 0 39 4172 026733 TIRUVALLA INDIA 318 B 4 08-2018 72 0 0 0 0 0 72 4172 028240 PALAI INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 153 2 0 0 0 2 155 4172 029338 PONKUNNAM INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 30 0 0 0 0 0 30 4172 036537 VAIKOM INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 30 0 0 0 -7 -7 23 4172 036779 MANNAR INDIA 318 B 4 08-2018 28 0 0 0 0 0 28 4172 037884 EDATHUA INDIA 318 B 4 08-2018 37 1 0 0 0 1 38 4172 039106 KOTTAYAM GANDHINAGAR INDIA 318 B 4 06-2018 50 0 0 0 0 0 50 4172 039381 RANNY INDIA 318 B 4 06-2018 44 0 0 0 0 0 44 4172 041266 CHINGAVANAM INDIA 318 B 4 08-2018 41 0 0 0 0 0 41 4172 042731 ERATTUPETTA INDIA 318 B 4 04-2018 92 0 0 0 0 0 92 4172 043954 MANIMALA INDIA 318 B 4 07-2018 37 0 0 0 0 0 37 4172 045851 KOZHENCHERRY INDIA 318 B 7 08-2018 36 0 0 0 -1 -1 35 4172 051425 KATTANAM INDIA 318 B 4 08-2018 22 0 0 0 0 0 22 4172 051770 ETTUMANOOR INDIA 318 B 4 06-2018 51 0 0 0 0 0 51 4172 052090 CHENGANNOOR INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 50 1 2 0 -3 0 50 4172 052386 MAVELIKKARA GREATER INDIA 318 B 4 06-2018 30 0 0 0 0 0 30 4172 052913 KONNI INDIA 318 B 4 09-2018 31 0 0 0 -1 -1 30 4172 -

DEPARTMENT of HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION 9 Physics

No. EX II (2)/00001/HSE/2017 DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM - MARCH 2017 LIST OF EXTERNAL EXAMINERS (Centre wise) 9 Physics District: Pathanamthitta Sl.No School Name External Examiner External's School No. Of Batches 1 03001 : GOVT. BHSS, ADOOR, BEENA G 03031 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N V HSS, ANGADICAL SOUTH, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04734285751, 9447117229 <=15 2 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, MANJU.V.L 03041 8 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Junior (Physics) K.R.P.M. HSS, SEETHATHODE, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9495764711 <=15 3 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, THOMAS CHACKO 03010 4 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT BOYS Ph: Ph: , 9446100754 HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA,PATH ANAMTHITTA 30 4 03003 : GOVT. HSS, BIJU PHILIP 03050 6 EZHUMATTOOR, HSST Senior (Physics) TECHNICAL HSS, MALLAPPALLY EAST.P.O, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: 04812401131, 9447414839 10 Ph: PATHANAMTHITTA, 689584 5 03004 : GOVT.HSS, SHEEBA VARGHESE 03045 7 KADAMMANITTA, HSST Senior (Physics) MT HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: , 9447223589 10 Ph: 6 03005 : K annasa Smaraka GOVT HSS, JESSAN VARUGHESE 03016 8 KADAPRA, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) M G M HSS, THIRUVALLA, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04692702200, 9496212211 10 7 03006 : GOVT HSS, KALANJOOR, LEKSHMI.P.S 03009 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT HSS KONNI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9447086029 14 8 03007 : GOVT HSS, VECHOOCHIRA RAJIMOL P R 03026 4 COLONY, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N D P HSS, VENKURINJI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04735266367, 9495554912 <=15 9 03008 : GOVT -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-B SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 12 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 14 8 Important Statistics 16 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 20 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 25 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 33 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 41 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 49 (vi) Sub-District Primary Census Abstract Village/Town wise 57 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 89 Gram Panchayat Primary Census Abstract-C.D. -

Members of the Local Authorities Alappuzha District

Price. Rs. 150/- per copy UNIVERSITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate by the member of the Local Authorities- (Under Section 17-Elected Members (7) of the Kerala University Act 1974) Electoral Roll of the Members of the Local Authorities-Alappuzha District Name of Roll Local No. Authority Name of member Address 1 LEKHA.P-MEMBER SREERAGAM, KARUVATTA NORTH PALAPPRAMBILKIZHAKKETHIL,KARUVATTA 2 SUMA -ST. NORTH 3 MADHURI-MEMBER POONTHOTTATHIL,KARUVATTA NORTH 4 SURESH KALARIKKAL KALARIKKALKIZHAKKECHIRA, KARUVATTA 5 CHANDRAVATHY.J, VISHNUVIHAR, KARUVATTA 6 RADHAMMA . KALAPURAKKAL HOUSE,KARUVATTA 7 NANDAKUMAR.S KIZHAKKEKOYIPURATHU, KARUVATTA 8 SULOCHANA PUTHENKANDATHIL,KARUVATTA 9 MOHANAN PILLAI THUNDILVEEDU, KARUVATTA 10 Karuvatta C.SUJATHA MANNANTHERAYIL VEEDU,KARUVATTA 11 K.R.RAJAN PUTHENPARAMBIL,KARUVATTA Grama Panchayath Grama 12 AKHIL.B CHOORAKKATTU HOUSE,KARUVATTA 13 T.Ponnamma- ThaichiraBanglow,Karuvatta P.O, Alappuzha 14 SHEELARAJAN R.S BHAVANAM,KARUVATTA NORTH MOHANKUMAR(AYYAPP 15 AN) MONEESHBHAVANAM,KARUVATTA 16 Sosamma Louis Chullikkal, Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 17 Jayamohan Shyama Nivas, Pollethai.P.O 18 Kala Thamarappallyveli,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 19 Dinakaran Udamssery,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 20 Rema Devi Puthenmadam, Kalvoor. P.O, Alappuzha 21 Indira Thilakan Pandyalakkal, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 22 V. Sethunath Kunnathu, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 23 Reshmi Raju Rajammalayam, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 24 Muthulekshmi Castle, Pathirappaly.P.O, Alappuzha 25 Thresyamma( Marykutty) Chavadiyil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 26 Philomina (Suja) Vadakkan parambil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha Grama Panchayath Grama 27 South Mararikulam Omana Moonnukandathil, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 28 Alice Sandhyav Vavakkad, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 29 Laiju. M Madathe veliyil , Pathirappally P O 30 Sisily (Kunjumol Shaji) Puthenpurakkal, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 31 K.A. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 06.12.2020To12.12.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 06.12.2020to12.12.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Ayyankeri Nikarth CR.1734/2020 30 12-12-2020 JFMC II 1 Vishnu Vijayan Panavally P.o Poochakal PS U/s 279 IPC & POOCHAKAL Shaji P.H Male 19:10 CHERHALA Panavally P/W-16 194 (1) MV Act CR.2663/2020 U/s 269 IPC & 118(e) of KP Act & Sec. 36 KIZHAKKE VEETTIL CHAKKARAKKU 12-12-2020 4(2)(j) r/w 5 of MANOJAN S, SI JFMC I 2 RATHEESH GOPI CHERTALA Male KARIKKAD P O LAM 18:30 Kerala OF POLICE CHERTHALA Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 THUNDUTHARA CR.1002/2020 KRISHNAKUM KARUTHAKUN 36 VADAKKATHIL, KAREELAKULA 12-12-2020 KAREELAKUL SUNUMON K, JFMC II 3 U/s 118(a) of AR JU Male MUTTOM PO, NGARA 17:20 ANGARA SI OF POLICE HARIPAD KP Act CHEPPAD THEKETHARA KIDASSERIL CR.1692/2020 JFMC PRABHAKARA 60 CHANDRAPURI VEEDU 12-12-2020 KAYAMKULA 4 PRADEEP KADAVU,DEVIK U/s 15(c) OF JYOTHIKUMAR KAYAMKULA N Male VARANAPPALLY MURI 17:20 M ULANGARA KA ACT M PUTHUPPALLY Kottakeril Vaduthala 20 12-12-2020 CR.1732/2020 JFMC II 5 Jamal Sageer Ahmed Sageer Jetty P.o Arookutty Vaduthala POOCHAKAL Shaji P.H Male 14:10 U/s 279 IPC CHERHALA P/W-7 Kochuveettil, JFMC I 22 Venmony Thazham 12-12-2020 CR.1157/2020 6 Afsal Ibrahim kutty kalyathra VENMANI Pradeep S CHENGANNU Male Muri, Venmony 14:20 U/s 279 IPC R Village Chaprayil -

Hand Book 2006-07

CO-OPERATIVE IN KERALA STATISTICAL ABSTRACT 2006-2007 HAND BOOK Prepared by: STATISTICS WING O/o THE REGISTRAR OF CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETIES, KERALA PREFACE This hand book contains the basic and important data relating to the working of different sectors of Co-operative movement in Kerala during the year 2006-07 This is the 27th annual publication in the series I hope that this hand book will serve as a useful material relating to all Co-operative activities in the State under the administrative control of the Registrar of Co-operative Societies. This book has been prepared by Statistics section of this office S/d Thiruvananthapuram Rani George I.A.S 07/01/2011 Registrar of Co-operative Societies SOME BASIC DATA OF KERALA Location : North latitude between 8o 18' and 12o 48' East longitude between 74o 52' and 77o 22' Area : 38863 sq. Km. Population : 31838619 (2001 Census) Male : 15468664 Female : 16369955 Population Density : 819 persons per sq. Km. Literacy : 90.92% Male literacy : 94.02% Female literacy : 87.86% Birth Rate : 17.30% Death Rate : 6.00% Infant Mortality Rate : 11.00% Sex Ratio : 1058 Women for 1000 men Number of Districts : 14 Number of Taluks : 63 Number of Revenue Villages : 1453 Number of Municipal Corporations : 5 Number of Municipalities : 53 Number of Township : 1 Number of Cantonment 1 Number of District panchayaths 14 Number of Block panchayaths 152 Number of Grama panchayaths 999 CONTENTS Table No. Type of Societies Page No. No.of Societies under the Administrative control of Registrar of 1 1 Co-operative Societies -

A Preliminary Study on the Odonate Diversity of Randapuncha Wetland, Kulanada, Pathanamthitta District, Kerala

RESEARCH ARTICLE ISSN: 2319-6955 A PRELIMINARY STUDY ON THE ODONATE DIVERSITY OF RANDAPUNCHA WETLAND, KULANADA, PATHANAMTHITTA DISTRICT, KERALA SREELEKSHMI S. AND ABHILASH R. Department of Zoology, Christian College, Chengannur, Kerala, India. Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract: Dragonflies and Damselflies are among the most attractive creatures on earth belonging to the most popular insect order Odonata .Odonata constitute a small well known order of insects that are widely distributed over the world .A study was carried out to assess the Odonata fauna of Randam Puncha wetland near Kulanada in Pathanamthitta district from the first week of April to second week of June 2016. A total of 18 species of Odonates representing 3 families were recorded from Randam Puncha, Kulanada during the study period. Dragon flies represented by the families Libellulidae and Gomphidae and damsel flies represented by the family Coenagrionidae were observed. Acisoma panorpoides, Aethrimanta brevipennis, Brachydiplax chalybea, Rhyothemis veriegata and Orthetrum sabina were the common dragon flies spotted on the site. On the basis of total number of individuals recorded,Libellulidae was the most dominant family. The Shannon-Weiner diversity index recorded a higher value of 2.405 in Randam Puncha and the Margalef species richness was 2.409. The values of Pielou’s evenness index 0.652 showed medium even distribution of species; the dominance index recorded was 0.895. Even though any rare or endangered species were not recorded in the present study, the Randam Puncha wetland showed rich odonate diversity and abundance. Keywords: Odonata, Dragonfly, Damselfly, Diversity Indices INTRODUCTION species have been reported within the The order Odonata comprising both geographic limits of India so far (Joshi et dragonflies and damselflies are believed to al.,2017). -

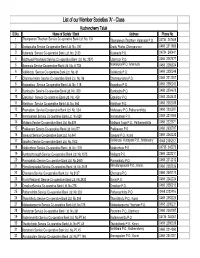

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. -

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church SABHA PRATHINIDHI MANDALAM 2017 - 2020 Address List of Mandalam Members Report Date: 27/07/2017 DIOCESE - ALL Page 1 of 46

Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church SABHA PRATHINIDHI MANDALAM 2017 - 2020 Address List of Mandalam Members Report Date: 27/07/2017 DIOCESE - ALL Page 1 of 46 L001 (NORTH CAROLINA MTC) L002 (LUBBOCK EMMANUEL) L003 (ATLANTA HERMON) MRS. VIJI MATHEW DR. P.JOHN LINCOLN MR. SAGIN K.MAMMAN 12700, RICHMOND RUN DRIVE 2404 YORK AVENUE 1960 SPRING MIST TERRACE RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, 27614 LUBBOCK, TEXAS 79407 LAWRENCE VILLE, GA - 30043 U.S.A U.S.A U.S.A 919-562-8167, 919-795-8409 8067976000, 8064415131 6783760015, 404 229 7054 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] L004 (TORONTO ST MATHEWS) L005 (BOSTON CARMEL) L006 (CHICAGO ST THOMAS) MR. JACOB JOSEPH MRS. MOLLY KURIAN MR. C.VARUGHESE PHILIP 2507 GRAND OAK TRAIL, OAK VILLE 43 DELANEY STREET,STOW, 1481 AUTUMN TRL. ONTARIO, CANADA- L6MOR7 MA- 01775 ADDISON, IL-60101 001 289 8373171, 001 905 399 6180 U.S.A U.S.A [email protected] 978 897 1260,978 793 1711 630-250-0619, 630-222-7021 [email protected] [email protected] L007 (PHILADELPHIA BETHEL) L008 (CONNECTICUT JERUSALEM) L009 (AUSTIN MTC) MRS. DEENAMMA THOMAS MR. MATHEWS THOMAS MR. SABU T.CHERIYAN 1137 ALTON PLACE 19 CEDAR ST. 2316 PARADISE RIDGE DR. PHILADELPHIA, P.A - 19115 DANBURY, CT-06811 ROUND ROCK, U.S.A U.S.A TEXAS 76665-7911, U.S.A 215 342 0237, 2672707974 203 205 0659, 203 312 4105 512 341 8084, 512 468 4457 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] L010 (KATTANAM ST THOMAS) L011 (EDMONTON TRINITY) L012 (SALEM M.T.C EASTERN LONG EVANG. -

1.0 Executive Summary

Granite Building Stone Quarry of Mr. Aji M Thomas at Sy. No. 381/1 pt, 381/3-1 pt and 384/4-1 pt of Chenneerkara Village, Kozhenchery Taluk, Pathanamthitta District Pre-Feasibility Report 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY S.No Particulars Details 1 Name of Project Proposed Granite Building Stone Quarry of Mr. Aji M Thomas 2 Project Proponent Mr. Aji M Thomas, Mullamkuzhiyil House, Prakkanam P.O, Pathanamthitta District, Kerala State- 689 643. 3 Village Chenneerkara 4 Taluk Kozhenchery 5 District Pathanamthitta 6 State Kerala 7 Co-ordinates 1 N 9015’ 56.00” E 760 44’ 42.67” 2 N 9015’ 56.54” E 760 44’ 41.51” 3 N 9015’ 56.65” E 760 44’ 41.51” 4 N 9015’ 56.78” E 760 44’ 41.48” 5 N 9015’ 57.15” E 760 44’ 41.20” 6 N 9015’ 57.08” E 760 44’ 40.66” 7 N 9015’ 57.24” E 760 44’ 40.25” 8 N 9015’ 56.11” E 760 44’ 38.85” 9 N 9015’ 55.97” E 760 44’ 38.96” 10 N 9015’ 55.73” E 760 44’ 39.68” 11 N 9015’ 55.75” E 760 44’ 40.74” 12 N 9015’ 55.13” E 760 44’ 41.18” 8 Topography Hilly Terrain 9 Topo Sheet No 58C/11 10 Elevation The highest elevation of the Permit area is 92 m MSL and lowest elevation is 68 m MSL. 11 Mining Lease Area 0.4011 Ha 12 Production capacity Total production is 61940 MT for two years. Maximum production capacity of 35162 MT achieved in Second year 13 Extent of mechanization Semi mechanized Opencast Mining 14 Depth of Mining 34 m 15 Life of Mining 2 years 16 Water requirement & source 10 KLD from open well and Water Cans(Drinking) 17 Man Power requirement 16 18 Project Cost Rs 40,50,000/- 1 Granite Building Stone Quarry of Mr.