Current Patterns Over the Continental Shelf and Slope Marlene A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continental Shelf the Last Maritime Zone

Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone The Last Maritime Zone Published by UNEP/GRID-Arendal Copyright © 2009, UNEP/GRID-Arendal ISBN: 978-82-7701-059-5 Printed by Birkeland Trykkeri AS, Norway Disclaimer Any views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP/GRID-Arendal or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this book do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authority, or deline- ation of its frontiers and boundaries, nor do they imply the validity of submissions. All information in this publication is derived from official material that is posted on the website of the UN Division of Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), which acts as the Secretariat to the Com- mission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS): www.un.org/ Depts/los/clcs_new/clcs_home.htm. UNEP/GRID-Arendal is an official UNEP centre located in Southern Norway. GRID-Arendal’s mission is to provide environmental informa- tion, communications and capacity building services for information management and assessment. The centre’s core focus is to facili- tate the free access and exchange of information to support decision making to secure a sustainable future. www.grida.no. Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Authors and contributors Tina Schoolmeester and Elaine Baker (Editors) Joan Fabres Øystein Halvorsen Øivind Lønne Jean-Nicolas Poussart Riccardo Pravettoni (Cartography) Morten Sørensen Kristina Thygesen Cover illustration Alex Mathers Language editor Harry Forster (Interrelate Grenoble) Special thanks to Yannick Beaudoin Janet Fernandez Skaalvik Lars Kullerud Harald Sund (Geocap AS) Continental Shelf The Last Maritime Zone Foreword During the past decade, many coastal States have been engaged in peacefully establish- ing the limits of their maritime jurisdiction. -

Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in The

Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam— Measurements and Modeling of Waves, Currents, Temperature, Salinity, and Turbidity, April–August 2012 Open-File Report 2014–1130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey FRONT COVER: Left: Photograph showing the impact of intentionally set wildfires on the land surface of War in the Pacific National Historical Park. Right: Underwater photograph of some of the healthy coral reefs in War in the Pacific National Historical Park. Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam— Measurements and Modeling of Waves, Currents, Temperature, Salinity, and Turbidity, April–August 2012 By Curt D. Storlazzi, Olivia M. Cheriton, Jamie M.R. Lescinski, and Joshua B. Logan Open-File Report 2014–1130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2014 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Suggested citation: Storlazzi, C.D., Cheriton, O.M., Lescinski, J.M.R., and Logan, J.B., 2014, Coastal circulation and water-column properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam—Measurements and modeling of waves, currents, temperature, salinity, and turbidity, April–August 2012: U.S. -

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Hydrothermal Vent Fields and Chemosynthetic Biota on the World's

ARTICLE Received 13 Jul 2011 | Accepted 7 Dec 2011 | Published 10 Jan 2012 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1636 Hydrothermal vent fields and chemosynthetic biota on the world’s deepest seafloor spreading centre Douglas P. Connelly1,*, Jonathan T. Copley2,*, Bramley J. Murton1, Kate Stansfield2, Paul A. Tyler2, Christopher R. German3, Cindy L. Van Dover4, Diva Amon2, Maaten Furlong1, Nancy Grindlay5, Nicholas Hayman6, Veit Hühnerbach1, Maria Judge7, Tim Le Bas1, Stephen McPhail1, Alexandra Meier2, Ko-ichi Nakamura8, Verity Nye2, Miles Pebody1, Rolf B. Pedersen9, Sophie Plouviez4, Carla Sands1, Roger C. Searle10, Peter Stevenson1, Sarah Taws2 & Sally Wilcox11 The Mid-Cayman spreading centre is an ultraslow-spreading ridge in the Caribbean Sea. Its extreme depth and geographic isolation from other mid-ocean ridges offer insights into the effects of pressure on hydrothermal venting, and the biogeography of vent fauna. Here we report the discovery of two hydrothermal vent fields on theM id-Cayman spreading centre. The Von Damm Vent Field is located on the upper slopes of an oceanic core complex at a depth of 2,300 m. High-temperature venting in this off-axis setting suggests that the global incidence of vent fields may be underestimated. At a depth of 4,960 m on the Mid-Cayman spreading centre axis, the Beebe Vent Field emits copper-enriched fluids and a buoyant plume that rises 1,100 m, consistent with > 400 °C venting from the world’s deepest known hydrothermal system. At both sites, a new morphospecies of alvinocaridid shrimp dominates faunal assemblages, which exhibit similarities to those of Mid-Atlantic vents. 1 National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK. -

Part 3. Oceanic Carbon and Nutrient Cycling

OCN 401 Biogeochemical Systems (11.03.11) (Schlesinger: Chapter 9) Part 3. Oceanic Carbon and Nutrient Cycling Lecture Outline 1. Models of Carbon in the Ocean 2. Nutrient Cycling in the Ocean Atmospheric-Ocean CO2 Exchange • CO2 dissolves in seawater as a function of [CO2] in the overlying atmosphere (PCO2), according to Henry’s Law: [CO2]aq = k*PCO2 (2.7) where k = the solubility constant • CO2 dissolution rate increases with: - increasing wind speed and turbulence - decreasing temperature - increasing pressure • CO2 enters the deep ocean with downward flux of cold water at polar latitudes - water upwelling today formed 300-500 years ago, when atmospheric [CO2] was 280 ppm, versus 360 ppm today • Although in theory ocean surface waters should be in equilibrium with atmospheric CO2, in practice large areas are undersaturated due to photosythetic C-removal: CO2 + H2O --> CH2O + O2 The Biological Pump • Sinking photosynthetic material, POM, remove C from the surface ocean • CO2 stripped from surface waters is replaced by dissolution of new CO2 from the atmosphere • This is known as the Biological Pump, the removal of inorganic carbon (CO2) from surface waters to organic carbon in deep waters - very little is buried with sediments (<<1% in the pelagic ocean) -most CO2 will ultimately be re-released to the atmosphere in zones of upwelling - in the absence of the biological pump, atmospheric CO2 would be much higher - a more active biological pump is one explanation for lower atmospheric CO2 during the last glacial epoch The Role of DOC and -

Tube-Nosed Seabirds) Unique Characteristics

PELAGIC SEABIRDS OF THE CALIFORNIA CURRENT SYSTEM & CORDELL BANK NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY Written by Carol A. Keiper August, 2008 Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary protects an area of 529 square miles in one of the most productive offshore regions in North America. The sanctuary is located approximately 43 nautical miles northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco California. The prominent feature of the Sanctuary is a submerged granite bank 4.5 miles wide and 9.5 miles long, which lay submerged 115 feet below the ocean’s surface. This unique undersea topography, in combination with the nutrient-rich ocean conditions created by the physical process of upwelling, produces a lush feeding ground. for countless invertebrates, fishes (over 180 species), marine mammals (over 25 species), and seabirds (over 60 species). The undersea oasis of the Cordell Bank and surrounding waters teems with life and provides food for hundreds of thousands of seabirds that travel from the Farallon Islands and the Point Reyes peninsula or have migrated thousands of miles from Alaska, Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. Cordell Bank is also known as the albatross capital of the Northern Hemisphere because numerous species visit these waters. The US National Marine Sanctuaries are administered and managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who work with the public and other partners to balance human use and enjoyment with long-term conservation. There are four major orders of seabirds: 1) Sphenisciformes – penguins 2) *Procellariformes – albatross, fulmars, shearwaters, petrels 3) Pelecaniformes – pelicans, boobies, cormorants, frigate birds 4) *Charadriiformes - Gulls, Terns, & Alcids *Orders presented in this seminar In general, seabirds have life histories characterized by low productivity, delayed maturity, and relatively high adult survival. -

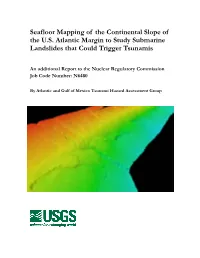

Seafloor Mapping of the Continental Slope of the U.S. Atlantic Margin to Study Submarine Landslides That Could Trigger Tsunamis

Seafloor Mapping of the Continental Slope of the U.S. Atlantic Margin to Study Submarine Landslides that Could Trigger Tsunamis An additional Report to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission Job Code Number: N6480 By Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Tsunami Hazard Assessment Group Seafloor Mapping of the Continental Slope of the U.S. Atlantic Margin to Study Submarine Landslides that Could Trigger Tsunamis An Additional Report to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission By Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Tsunami Hazard Assessment Group: Uri ten Brink, David Twichell, Jason Chaytor, Bill Danforth, Brian Andrews, and Elizabeth Pendleton U.S. Geological Survey, Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA This reports provides additional information to the report Evaluation of Tsunami Sources with Potential to Impact the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, submitted to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission on August 22, 2008. October 15, 2010 NOTICE FROM USGS This publication was prepared by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed in this report, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference therein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. Any views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. -

Chapter 8 the Pacific Ocean After These Two Lengthy Excursions Into

Chapter 8 The Pacific Ocean After these two lengthy excursions into polar oceanography we are now ready to test our understanding of ocean dynamics by looking at one of the three major ocean basins. The Pacific Ocean is not everyone's first choice for such an undertaking, mainly because the traditional industrialized nations border the Atlantic Ocean; and as science always follows economics and politics (Tomczak, 1980), the Atlantic Ocean has been investigated in far more detail than any other. However, if we want to take the summary of ocean dynamics and water mass structure developed in our first five chapters as a starting point, the Pacific Ocean is a much more logical candidate, since it comes closest to our hypothetical ocean which formed the basis of Figures 3.1 and 5.5. We therefore accept the lack of observational knowledge, particularly in the South Pacific Ocean, and see how our ideas of ocean dynamics can help us in interpreting what we know. Bottom topography The Pacific Ocean is the largest of all oceans. In the tropics it spans a zonal distance of 20,000 km from Malacca Strait to Panama. Its meridional extent between Bering Strait and Antarctica is over 15,000 km. With all its adjacent seas it covers an area of 178.106 km2 and represents 40% of the surface area of the world ocean, equivalent to the area of all continents. Without its Southern Ocean part the Pacific Ocean still covers 147.106 km2, about twice the area of the Indian Ocean. Fig. 8.1. The inter-oceanic ridge system of the world ocean (heavy line) and major secondary ridges. -

Biological Oceanography - Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun

OCEANOGRAPHY – Vol.II - Biological Oceanography - Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun BIOLOGICAL OCEANOGRAPHY Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun Laboratoire d'Océanographie de Villefranche, France. Keywords: Algae, allochthonous nutrient, aphotic zone, autochthonous nutrient, Auxotrophs, bacteria, bacterioplankton, benthos, carbon dioxide, carnivory, chelator, chemoautotrophs, ciliates, coastal eutrophication, coccolithophores, convection, crustaceans, cyanobacteria, detritus, diatoms, dinoflagellates, disphotic zone, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), dissolved organic matter (DOM), ecosystem, eukaryotes, euphotic zone, eutrophic, excretion, exoenzymes, exudation, fecal pellet, femtoplankton, fish, fish lavae, flagellates, food web, foraminifers, fungi, harmful algal blooms (HABs), herbivorous food web, herbivory, heterotrophs, holoplankton, ichthyoplankton, irradiance, labile, large planktonic microphages, lysis, macroplankton, marine snow, megaplankton, meroplankton, mesoplankton, metazoan, metazooplankton, microbial food web, microbial loop, microheterotrophs, microplankton, mixotrophs, mollusks, multivorous food web, mutualism, mycoplankton, nanoplankton, nekton, net community production (NCP), neuston, new production, nutrient limitation, nutrient (macro-, micro-, inorganic, organic), oligotrophic, omnivory, osmotrophs, particulate organic carbon (POC), particulate organic matter (POM), pelagic, phagocytosis, phagotrophs, photoautotorphs, photosynthesis, phytoplankton, phytoplankton bloom, picoplankton, plankton, -

Film Flight: Lost Production and Its Economic Impact on California

I MILKEN INSTITUTE California Center I July 2010 Film Flight: Lost Production and Its Economic Impact on California by Kevin Klowden, Anusuya Chatterjee, and Candice Flor Hynek Film Flight: Lost Production and Its Economic Impact on California by Kevin Klowden, Anusuya Chatterjee, and Candice Flor Hynek ACKnowLEdgmEnts The authors gratefully acknowledge Armen Bedroussian and Perry Wong for their expert assistance in preparing this study. We also thank our editor, Lisa Renaud. About tHE mILKEn InstItutE The Milken Institute is an independent economic think tank whose mission is to improve the lives and economic conditions of diverse populations in the United States and around the world by helping business and public policy leaders identify and implement innovative ideas for creating broad-based prosperity. We put research to work with the goal of revitalizing regions and finding new ways to generate capital for people with original ideas. We focus on: human capital: the talent, knowledge, and experience of people, and their value to organizations, economies, and society; financial capital: innovations that allocate financial resources efficiently, especially to those who ordinarily would not have access to them, but who can best use them to build companies, create jobs, accelerate life-saving medical research, and solve long-standing social and economic problems; and social capital: the bonds of society that underlie economic advancement, including schools, health care, cultural institutions, and government services. By creating ways to spread the benefits of human, financial, and social capital to as many people as possible— by democratizing capital—we hope to contribute to prosperity and freedom in all corners of the globe. -

Active Continental Margin

Encyclopedia of Marine Geosciences DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-6644-0_102-2 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 Active Continental Margin Serge Lallemand* Géosciences Montpellier, University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France Synonyms Convergent boundary; Convergent margin; Destructive margin; Ocean-continent subduction; Oceanic subduction zone; Subduction zone Definition An active continental margin refers to the submerged edge of a continent overriding an oceanic lithosphere at a convergent plate boundary by opposition with a passive continental margin which is the remaining scar at the edge of a continent following continental break-up. The term “active” stresses the importance of the tectonic activity (seismicity, volcanism, mountain building) associated with plate convergence along that boundary. Today, people typically refer to a “subduction zone” rather than an “active margin.” Generalities Active continental margins, i.e., when an oceanic plate subducts beneath a continent, represent about two-thirds of the modern convergent margins. Their cumulated length has been estimated to 45,000 km (Lallemand et al., 2005). Most of them are located in the circum-Pacific (Japan, Kurils, Aleutians, and North, Middle, and South America), Southeast Asia (Ryukyus, Philippines, New Guinea), Indian Ocean (Java, Sumatra, Andaman, Makran), Mediterranean region (Aegea, Cala- bria), or Antilles. They are generally “active” over tens (Tonga, Mariana) or hundreds (Japan, South America) of millions of years. This longevity has consequences on their internal structure, especially in terms of continental growth by tectonic accretion of oceanic terranes, or by arc magmatism, but also sometimes in terms of continental consumption by tectonic erosion. Morphology A continental margin generally extends from the coast down to the abyssal plain (see Fig. -

Seasonal and Spatial Fluctuations of the Phytoplankton in Monterey Bay

SEASONAL AND SPATIAL FLUCTUATIONS OF THE PHYTOPLANKTON IN MONTEREY BAY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of California State University, Hayward In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Biological Science by Russ Waidelich January, 1976 ABSTRACT The seasonal and spatial fluctuations of phyto plankton in Monterey Bay were described for an 18-month period. Low winter levels were mainly due to instabi lity of the water column, while the spring bloom was brought a·bout by the commencement of upwelling and the subsequent stabilization of the water column, with resi dence time of water regulating chlorophyll concentra tions. The summer minimum shortly followed the cessa tion of upwelling, when it appeared that nitrates were limiting, although zooplankton was a major factor in re ducing the algal standing stock at this time. Adequate illumination and relaxation of grazing pressure rather than specificity of water type appeared to be the major factors regulating the occurrence of the fall bloom, indicating that the seasonal pattern of Monterey Bay conforms generally to that of the mid latitude marine ecosystems. An examination of the spatial distribution o.f phytoplankton revealed lower values over the canyon during upwelling months due to advection of water to the shelf areas, and lower values in the same area during non-upwelling months due to subsidence or downwelling and tur·bul enc e . ii ACENOWLEDGlVJENTS Many people were responsible for helping to make this thesis possible. I would first like to thank my major advisors, Dr. Mary Silver and Dr. John Martin, for their valuable advice and support.