Appendix III Folklore Versus History: the Tantura Blood Libel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Palestine : Index Gazetteer

PA L. ES. T I N E \. \> FH.C: S."Tl fl e (I) PREFACE 1. MAPS USED This Index Gazetteer is compiled from the 16 sheets or the 1/100.000 Palestine series PDR/1512/3776-91, the 1/250.000 South sheet PDR/1509/3951 for the area between the Egyptian Frontier and 35° E (Easting 150) and south or grid north 040, and from five sheets of the 1/100.000 South Levant series PDR/1522 whi~h cover the area between 35 ° E and the Trans-Jordan border south of grid north 040. 2. TRANSLITERATION Names are transliterated according to the "Rules or Transliteration.-Notice regarding Transliteration in English or .Arabic names" issued by the Government of Pale• stine (Palestine Gazette~o. 1133 of 2-0ct-41), but without Using the diacritical signs of this system. As.there are many similar characters in the Arabic· and Hebrew alphabets the following li~t of alternative letters Should.be consulted if a name is not found under the letter it is looked tor:- a-e e.g.:- Tall, Tell, ar-er, al-el c - s - ts - ·z Saghira, ·Tsiyon, Zion d - dh Dhahrat g - j Jabal, Jisr h - kh Hadera, Khudeira k - q Karm, Qevutsa, Qibbuts 3. GRID REFERENCES Definite points such as villages, trig.points etc.· have been given the reference of the kilometre. s~uare in which they are situated. In all other cases .the reference is to the square in which the first letter of the name is printed. Names of rivers and wadis which appear more than once have been treated as follows:- The map reference of the name which is nearest the source and that of the one farthest downstream have both been listed. -

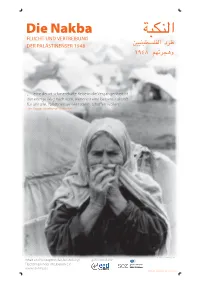

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

United Nations Conciliation.Ccmmg3sionfor Paiestine

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION.CCMMG3SIONFOR PAIESTINE RESTRICTEb Com,Tech&'Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX J$ NON - JlXWISHPOPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARXESHELD BY THE ISRAEL DBFENCEARMY ON X5.49 AS ON 1;4-,45 IN ACCORDANCEWITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SUMMARY..,,... 1 ACRE SUB DISTRICT . , , . 2 - 3 SAPAD II . c ., * ., e .* 4-6 TIBERIAS II . ..at** 7 NAZARETH II b b ..*.*,... 8 II - 10 BEISAN l . ,....*. I 9 II HATFA (I l l ..* a.* 6 a 11 - 12 II JENIX l ..,..b *.,. J.3 TULKAREM tt . ..C..4.. 14 11 JAFFA I ,..L ,r.r l b 14 II - RAMLE ,., ..* I.... 16 1.8 It JERUSALEM .* . ...* l ,. 19 - 20 HEBRON II . ..r.rr..b 21 I1 22 - 23 GAZA .* l ..,.* l P * If BEERSHEXU ,,,..I..*** 24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH'POPULATION Within the boundaries held 6~~the Israel Defence Army on 1.5.49 . AS ON 1.4.45 Jrr accordance with-. the Palestine Gp~ernment Village ‘. Statistics, April 1945, . SUB DISmICT MOSLEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11,150 6,940 65,380 SAFAD 44,510 1,630 780 46,920 TJBERIAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 Xl, 040 3 38,500 BEISAN lT,92o 650 20 16,590 HAXFA 85,590 30,200 4,330 120,520 JENIN 8,390 60 8,450 TULJSAREM 229310, 10 22,320' JAFFA 93,070 16,300 330 1o9p7oo RAMIIEi 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 I 47,740 HEBRON 19,810 10 19,820 GAZA 69,230 160 * 69,390 BEERSHEBA 53,340 200 10 53,m TOT$L 621,030 92,060 13,710 7z6,8oo . -

Notorious Massacres of Palestinians Between 1937 & 1948

Notorious massacres of Palestinians between 1937 & 1948 Notorious massacres of Palestinians between 1937 & 1948 FACT SHEET | May 2013 middleeastmonitor.com Notorious massacres of Palestinians between 1937 & 1948 According to hundreds of Palestinian, Arab, Israeli, and Western sources, both written and oral, Zionist forces committed dozens of massacres against Palestinians during what was called the 1948 “war”. Some of these are well-known and have been published while others are not. Below are some of the details of the most notorious massacres committed at the hands of Haganah and its armed wing, the Palmach, as well as the Stern Gang, the Irgun and other Zionist mobs: • The Jerusalem Massacre - 1/10/1937 A member of the Irgun Zionist organisation detonated a bomb in the vegetable market near the Damascus (Nablus) Gate in Jerusalem killing dozens of Arab civilians and wounding many others. • The Haifa Massacre - 6/3/1937 Terrorists from the Irgun and Lehi Zionist gangs bombed a market in Haifa kill- ing 18 Arab civilians and wounding 38. • The Haifa Massacre - 6/7/1938 Terrorists from the Irgun Zionist gang placed two car bombs in a Haifa market killing 21 Arab civilians and wounding 52. • The Jerusalem Massacre - 13/7/1938 10 Arabs killed and 31 wounded in a massive explosion in the Arab vegetable market in the Old City. • The Jerusalem Massacre - 15/7/1938 A member of the Irgun Zionist gang threw a hand grenade in front of a mosque in Jerusalem as worshippers were walking out. 10 were killed and 30 were wounded. • The Haifa Massacre - 25/7/1938 A car bomb was planted by the Irgun Zionist gang in an Arab market in Haifa which killed 35 Arab civilians and wounded 70. -

Al Nakba Background

Atlas of Palestine 1917 - 1966 SALMAN H. ABU-SITTA PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY LONDON Chapter 3: The Nakba Chapter 3 The Nakba 3.1 The Conquest down Palestinian resistance to British policy. The The immediate aim of Plan C was to disrupt Arab end of 1947 marked the greatest disparity between defensive operations, and occupy Arab lands The UN recommendation to divide Palestine the strength of the Jewish immigrant community situated between isolated Jewish colonies. This into two states heralded a new period of conflict and the native inhabitants of Palestine. The former was accompanied by a psychological campaign and suffering in Palestine which continues with had 185,000 able-bodied Jewish males aged to demoralize the Arab population. In December no end in sight. The Zionist movement and its 16-50, mostly military-trained, and many were 1947, the Haganah attacked the Arab quarters in supporters reacted to the announcement of veterans of WWII.244 Jerusalem, Jaffa and Haifa, killing 35 Arabs.252 On the 1947 Partition Plan with joy and dancing. It December 18, 1947, the Palmah, a shock regiment marked another step towards the creation of a The majority of young Jewish immigrants, men established in 1941 with British help, committed Jewish state in Palestine. Palestinians declared and women, below the age of 29 (64 percent of the first reported massacre of the war in the vil- a three-day general strike on December 2, 1947 population) were conscripts.245 Three quarters of lage of al-Khisas in the upper Galilee.253 In the first in opposition to the plan, which they viewed as the front line troops, estimated at 32,000, were three months of 1948, Jewish terrorists carried illegal and a further attempt to advance western military volunteers who had recently landed in out numerous operations, blowing up buses and interests in the region regardless of the cost to Palestine.246 This fighting force was 20 percent of Palestinian homes. -

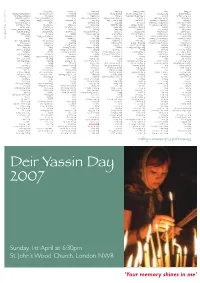

F-Dyd Programme

‘Your memory shines in me’ in shines memory ‘Your St. John’s Wood Church, London NW8 London Church, Wood John’s St. Sunday, 1st April at 6:30pm at April 1st Sunday, 2007 Deir Yassin Day Day Yassin Deir Destroyed Palestinian villages Amqa Al-Tira (Tirat Al-Marj, Abu Shusha Umm Al-Zinat Deir 'Amr Kharruba, Al-Khayma Harrawi Al-Zuq Al-Tahtani Arab Al-Samniyya Al-Tira Al-Zu'biyya) Abu Zurayq Wa'arat Al-Sarris Deir Al-Hawa Khulda, Al-Kunayyisa (Arab Al-Hamdun), Awlam ('Ulam) Al-Bassa Umm Ajra Arab Al-Fuqara' Wadi Ara Deir Rafat Al-Latrun (Al-Atrun) Hunin, Al-Husayniyya Al-Dalhamiyya Al-Birwa Umm Sabuna, Khirbat (Arab Al-Shaykh Yajur, Ajjur Deir Al-Shaykh Al-Maghar (Al-Mughar) Jahula Ghuwayr Abu Shusha Al-Damun Yubla, Zab'a Muhammad Al-Hilu) Barqusya Deir Yassin Majdal Yaba Al-Ja'una (Abu Shusha) Deir Al-Qasi Al-Zawiya, Khirbat Arab Al-Nufay'at Bayt Jibrin Ishwa', Islin (Majdal Al-Sadiq) Jubb Yusuf Hadatha Al-Ghabisyya Al-'Imara Arab Zahrat Al-Dumayri Bayt Nattif Ism Allah, Khirbat Al-Mansura (Arab Al-Suyyad) Al-Hamma (incl. Shaykh Dannun Al-Jammama Atlit Al-Dawayima Jarash, Al-Jura Al-Mukhayzin Kafr Bir'im Hittin & Shaykh Dawud) Al-Khalasa Ayn Ghazal Deir Al-Dubban Kasla Al-Muzayri'a Khirbat Karraza Kafr Sabt, Lubya Iqrit Arab Suqrir Ayn Hawd Deir Nakhkhas Al-Lawz, Khirbat Al-Na'ani Al-Khalisa Ma'dhar, Al-Majdal Iribbin, Khirbat (incl. Arab (Arab Abu Suwayrih) Balad Al-Shaykh Kudna (Kidna) Lifta, Al-Maliha Al-Nabi Rubin Khan Al-Duwayr Al-Manara Al-Aramisha) Jurdayh, Barbara, Barqa Barrat Qisarya Mughallis Nitaf (Nataf) Qatra Al-Khisas (Arab -

Financing Racism and Apartheid

Financing Racism and Apartheid Jewish National Fund’s Violation of International and Domestic Law PALESTINE LAND SOCIETY August 2005 Synopsis The Jewish National Fund (JNF) is a multi-national corporation with offices in about dozen countries world-wide. It receives millions of dollars from wealthy and ordinary Jews around the world and other donors, most of which are tax-exempt contributions. JNF aim is to acquire and develop lands exclusively for the benefit of Jews residing in Israel. The fact is that JNF, in its operations in Israel, had expropriated illegally most of the land of 372 Palestinian villages which had been ethnically cleansed by Zionist forces in 1948. The owners of this land are over half the UN- registered Palestinian refugees. JNF had actively participated in the physical destruction of many villages, in evacuating these villages of their inhabitants and in military operations to conquer these villages. Today JNF controls over 2500 sq.km of Palestinian land which it leases to Jews only. It also planted 100 parks on Palestinian land. In addition, JNF has a long record of discrimination against Palestinian citizens of Israel as reported by the UN. JNF also extends its operations by proxy or directly to the Occupied Palestinian Territories in the West Bank and Gaza. All this is in clear violation of international law and particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention which forbids confiscation of property and settling the Occupiers’ citizens in occupied territories. Ethnic cleansing, expropriation of property and destruction of houses are war crimes. As well, use of tax-exempt donations in these activities violates the domestic law in many countries, where JNF is domiciled. -

Sacred Landscape

The publisher and the author gratefully acknowledge the generous contributions to Sacred this book provided by the General Endowment Fund of the Associates of the University of California Press and by the United States Institute of Peace. Landscape THE BURIED HISTORY OF THE HOLY LAND SINCE 1948 Meron Benvenisti Translated by Maxine Kaufman-Lacusta UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS B RK Y LO ANG LES LONDON o I I LEBANON I Bassa (Shlomi) o 2 Kafr Birim (Baram) 3 Iqrit 30 0 \ ,------, Jewish state according to 260 2 ~IO) .Safad L-.J 1947 UN Partition Plan 4 Saffuriyya (Zippori) SYRIA 5 Qastal " °12 Arab state according to 6 Deir Yasin I 1947 UN Partition Plan (taken ,I c:::J " by Israel 1948-49) 7 Mishmar Haemeq 8 Ein Hawd .. -'\... .. The West Bank and 9 Ghabisiyya . ./ Gaza Strip 10 Safsaf (Sifsofa) 'Boundaries of Arab state (1947) 11 Kh. Jalama 12 Akbara MEDITERRANEAN Boundaries of Israel (1949) 13 Nabi Rubin SeA 14 Zakariyya (Zecharia) Jerusalem (internationalized) 15 Khisas 16 Yazur (Azor) JORDAN 17 Yahudiyya (Yahud) 18 Birwa (Ahihud) 19 Tantura (Dor) 20 Etzion Block 21 Balad ai-Sheikh (Nesher) 22 Abu Zureik 23 Ajjur (Agur) 24 Beit Atab 25 Yehiam (Jidin) 26 Sasa (Sasa) 27 Dawaima (Amazia) 28 Latroun 29 Hittin 30 Yibne (Yavne) , -, 31 Sataf \, I ,I , " Map 2. Eretz Israel/Palestine (1947-49) ••• '~j.: /1.(;: >, "~~,~ '{ 15 Jewish Houses in a Deserted Arab Village. The abandoned village of ~I-~aliha . I' hborhood Modern Jewish houses are built on t e s opes is today a Jerusa em nelg. .I . of the village hill, and renovated Arab houses surroun~ the deserted vii. -

Palestine Village Statistics

UNITED NATIONS CONCILIATION' COMMISSION FOR PAIESTINE RES TR IC TED Com,Tech/7/Add; 1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH APPENDIX B NON - JEWISH POPULATION WITHIN THE BOUNDARIES HBLD BY THE ISRAEL DEFENCE ARMY ON Urn IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE PALESTINE GOVERNMENT VILLAGE STATISTICS, APRIL 1945. CONTENTS Pages SubfMARY * a . * . * . a. , , . 1 ACRESUBDISTRICT ft . l ft. (I 2-3 SAFAD 11 *wb*a*.e+4u 4-6 T IBER IAS I I .a7 NAZARETH 11 *a**ea+*aaq 8 BE ISAN I I a 9-10 HA IPA I I . v. 11-12 JENIN tt 13 TULKAREM t I aaaa14 JAFFA II .a~I? RAMIE ~t , 16-18 JERUSALEM It 19-20 HEBRON t1 21 GAZA ~t baua22-23 BEERSHEBA .24 SUMMARY OF NON - JEWISH POPULATION Within the boundaries held by the Israel Defence Army . on 1.5.49 AS ON 1.4.45 In accordance with the Palestine Government Village * Statistics, April 1945. S UB DISTRICT MOS LEMS CHRIS TIANS OTHERS TOTAL ACRE 47,290 11 ,150 6,940 65,380 ' . SAFAD W-t, 510 19630 780 46,920 TIBER IAS 22,450 2,360 1,290 26,100 NAZARETH 27,460 l19@t0 W 38,500 BE ISAN 15,920 650 20 16 590 HA IFA 83,590 30,200 4,330 120,120 JENIN 89390 60 m 8,450 TULKAREM 22,310 10 22,320' JAFFA 93 9 070 16,300 330 109,700 RAMLE 76,920 5,290 10 82,220 JERUSALEM 34,740 13,000 M 47,740 HEBR ON 19,810 10 ..R 19,820 GAZA 69,230 l60 69,390 TOTAL 621,030 92 060 13 710 726,800 NON - JEWISH POPULATION ACRE SUB - DISTRICT VILLAGE M OS LEMS CHRISTIANS OTHERS TOTAL ABU S INAN ACRE AMQA ARRABA BASSA BEIT JANN & EIN EL ASAD B INA B IRWA BUQEIA DAMUN DEIR EL ASSAD DEIR EL HATO. -

The Nakba - in Memoriam

THE NAKBA - IN MEMORIAM At-Tira, 12 December 1947: Members of the Irgun forces raided the village south of Haifa, killing 13 and wounding 10 villagers. “Nakba Day” is commemorated annually on 15 May. The Nakba dates back to 1948 and in the eyes of the Palestinians was not a one-time occurrence, which is still going on today. Since that first wave of dispossession and displacement entire generations of Palestinians have been born scattered around the world and lived without justice and freedom. The conflict still endures and the events of the past are still shaping present-day Palestinian life, upholding the refugee problem, disintegrated an entire society, thwarting economic development, and keeping a nation broadly dependent upon international aid for survival. Jerusalem, Damascus Gate, 12 December 1947: A bomb attack by Irgun at Damascus Gate outside the Old City of Jerusalem, leaving 20 killed and 5 wounded. In 1915, the British government commissioned Sir Henry MacMahon to correspond with the Hashemite leader Sharif Hussein Ibn Ali of Mecca (known as Hussein-Sir Henry McMahon correspondence) to encourage him to ally with Britain against the Ottomans. In return MacMahon offered British official support for Arab independence and a unified Arab kingdom under Hashemite leadership. This assurance contributed to the outbreak of the Arab Revolt for independence from Ottoman rule of June 1916. Yehiday, 13 December 1947: Jewish forces disguised as a British army patrol entered the Arab village of Yehiday (near Petah Tikva), stopped in front of the coffee house and began shooting at the crowd gathered in the café, placed bombs next to homes, and tossed grenades at villagers, killing 7 and wounding many more, before being stopped by real British troops arriving and avoiding more deaths to occur.