The Claim for Recognition of Israel As a Jewish State a Reassessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forming a Nucleus for the Jewish State

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 Jewish Settlements 70 CE - 1882 ......................................................... 4 Forming a Nucleus for First Aliyah (1882-1903) ...................................................................... 5 Second Aliyah (1904-1914) .................................................................. 7 the Jewish State: Third Aliyah (1919-1923) ..................................................................... 9 First and Second Aliyot (1882-1914) ................................................ 11 First, Second, and Third Aliyot (1882-1923) ................................... 12 1882-1947 Fourth Aliyah (1924-1929) ................................................................ 13 Fifth Aliyah Phase I (1929-1936) ...................................................... 15 First to Fourth Aliyot (1882-1929) .................................................... 17 Dr. Kenneth W. Stein First to Fifth Aliyot Phase I (1882-1936) .......................................... 18 The Peel Partition Plan (1937) ........................................................... 19 Tower and Stockade Settlements (1936-1939) ................................. 21 The Second World War (1940-1945) ................................................ 23 Postwar (1946-1947) ........................................................................... 25 11 Settlements of October 5-6 (1947) ............................................... 27 First -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Judaism and Artistic Creativity: Despite Maimonides and Thanks to Him

MENACHEM KELLNER Judaism and Artistic Creativity: Despite Maimonides and Thanks to Him IN SEEKING TO UNDERSTAND the place of artistic creativity in Judaism, Maimonides hardly appears to be a promising source with which to start. His emphasis on intellectual perfection as the defining characteristic of humanity would not appear to make him a promising candidate for our project. This is all the more the case when we consider that, for him, intellectual perfection involves the apprehension of already established truth, not the creation of new knowledge. Despite this, I suggest that Maimonides can be very helpful in seeking to elaborate a Jewish approach to the value of artistic creativity. Maimonides may have been the first posek to count the imitation of God (imitatio Dei ) as a specific commandment of the Torah. Yea or nay, he certain - ly emphasized its importance. The first text in which Maimonides discusses the imitation of God is his Book of Commandments , positive commandment 8: Walking in God’s ways. By this injunction we are commanded to be like God (praised be He) as far as it is in our power. This injunction is con - tained in His words, And you shall walk in His ways (Deut. 28:9), and also in an earlier verse in His words, [ What does the Lord require of you, but to fear the Lord your God, ] to walk in all His ways? (Deut. 10:2). On this latter verse the Sages comment as follows: “Just as the Holy One, blessed be He, is called merciful [ rahum ], so should you be merciful; just as He is called gracious [ hanun ], so should you be gracious; just as he is called righteous [ tsadik ], so should you be righteous; just as He is called saintly MENACHEM KELLNER is Chair of the Department of Philosophy and Jewish Thought at Shalem College Jerusalem and Wolfson Professor Emeritus of Jewish Thought at the University of Haifa. -

Palestine : Index Gazetteer

PA L. ES. T I N E \. \> FH.C: S."Tl fl e (I) PREFACE 1. MAPS USED This Index Gazetteer is compiled from the 16 sheets or the 1/100.000 Palestine series PDR/1512/3776-91, the 1/250.000 South sheet PDR/1509/3951 for the area between the Egyptian Frontier and 35° E (Easting 150) and south or grid north 040, and from five sheets of the 1/100.000 South Levant series PDR/1522 whi~h cover the area between 35 ° E and the Trans-Jordan border south of grid north 040. 2. TRANSLITERATION Names are transliterated according to the "Rules or Transliteration.-Notice regarding Transliteration in English or .Arabic names" issued by the Government of Pale• stine (Palestine Gazette~o. 1133 of 2-0ct-41), but without Using the diacritical signs of this system. As.there are many similar characters in the Arabic· and Hebrew alphabets the following li~t of alternative letters Should.be consulted if a name is not found under the letter it is looked tor:- a-e e.g.:- Tall, Tell, ar-er, al-el c - s - ts - ·z Saghira, ·Tsiyon, Zion d - dh Dhahrat g - j Jabal, Jisr h - kh Hadera, Khudeira k - q Karm, Qevutsa, Qibbuts 3. GRID REFERENCES Definite points such as villages, trig.points etc.· have been given the reference of the kilometre. s~uare in which they are situated. In all other cases .the reference is to the square in which the first letter of the name is printed. Names of rivers and wadis which appear more than once have been treated as follows:- The map reference of the name which is nearest the source and that of the one farthest downstream have both been listed. -

Session of the Zionist General Council

SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1967 Addresses,; Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE n Library י»B I 3 u s t SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1966 Addresses, Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM iii THE THIRD SESSION of the Zionist General Council after the Twenty-sixth Zionist Congress was held in Jerusalem on 8-15 January, 1967. The inaugural meeting was held in the Binyanei Ha'umah in the presence of the President of the State and Mrs. Shazar, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Knesset, Cabinet Ministers, the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, the State Comptroller, visitors from abroad, public dignitaries and a large and representative gathering which filled the entire hall. The meeting was opened by Mr. Jacob Tsur, Chair- man of the Zionist General Council, who paid homage to Israel's Nobel Prize Laureate, the writer S.Y, Agnon, and read the message Mr. Agnon had sent to the gathering. Mr. Tsur also congratulated the poetess and writer, Nellie Zaks. The speaker then went on to discuss the gravity of the time for both the State of Israel and the Zionist Move- ment, and called upon citizens in this country and Zionists throughout the world to stand shoulder to shoulder to over- come the crisis. Professor Andre Chouraqui, Deputy Mayor of the City of Jerusalem, welcomed the delegates on behalf of the City. -

English/Deportation/Statistics

International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion Proceedings On Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Palestine Written Statement (30 January 2004) And Oral Pleading (23 February 2004) Preface 1. In October of 2003, increasing concern about the construction by Israel, the occupying Power, of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, in departure from the Armistice Line of 1949 (the Green Line) and deep into Palestinian territory, brought the issue to the forefront of attention and debate at the United Nations. The Wall, as it has been built by the occupying Power, has been rapidly expanding as a regime composed of a complex physical structure as well as practical, administrative and other measures, involving, inter alia, the confiscation of land, the destruction of property and countless other violations of international law and the human rights of the civilian population. Israel’s continued and aggressive construction of the Wall prompted Palestine, the Arab Group, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) to convey letters to the President of the United Nations Security Council in October of 2003, requesting an urgent meeting of the Council to consider the grave violations and breaches of international law being committed by Israel. 2. The Security Council convened to deliberate the matter on 14 October 2003. A draft resolution was presented to the Council, which would have simply reaffirmed, inter alia, the principle of the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force and would have decided that the “construction by Israel, the occupying Power, of a wall in the Occupied Territories departing from the armistice line of 1949 is illegal under relevant provisions of international law and must be ceased and reversed”. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

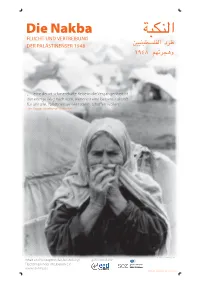

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

The Arab-Israeli Conflict from the Perspective of International Law

THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Yoram Dinstein* The Washington agreement of September 1993 between Israel and the Palestinians,1 has raised hopes worldwide that the Arab-Israeli conflict which has been raging for many decades (and in fact precedes the birth of the State of Israel) is drawing to a dose. In reality, while the Washington agreement undoubtedly represents a major breakthrough, it is premature to regard the conflict as settled. Many more agreements, not only with the Palestinians, will be required in order to augur a comprehensive peace in the Middle East. In the meantime, numerous issues remain unresolved and there is still much opposition in many circles to the idea of Arab-Israeli reconciliation. The need to study the international legal aspects of the conflict is, therefore, as topical today as it was in earlier days. The following observations on the Arab-Israeli conflict will be based on international law. No attempt will be made to examine “historical rights”. Moreover, no reference will be made here to justice or morality. History, justice and morality are constantly invoked by both parties to every conflict and, as a rule, they are neither helpful nor unequivocal. Being subjective perspectives, they are more conducive to the definition of the problem than to its solution. Unfortunately, the arguments heard on both sides of the Arab-Israeli conflict are frequently grounded on a confusing (not to say confused) combination of law, justice, morality and history. If the conflict is to be probed in a rational and hopefully productive way, it is imperative to identify the level on which the analysis is to be conducted.