Sport and National Identity in Taiwan: Some Preliminary Thoughts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Republik China in Der Olympischen Bewegung

Aus dem Institut für Sportgeschichte der Deutschen Sporthochschule Köln Geschäftsführender Leiter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Stephan Wassong Die Republik China in der Olympischen Bewegung von der Deutschen Sporthochschule Köln zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Ph.D. (Sport History) genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Yi-Ling Huang aus Nantou/Taiwan Köln 2012 Erster Referent: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Manfred Lämmer Zweiter Referent: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Karl Lennartz Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Bloch Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 5. Dezember 2012 Hierdurch versichere ich: Ich habe diese Arbeit selbständig und nur unter Benutzung der angegebenen Quellen und technischen Hilfen angefertigt; sie hat noch keiner anderen Stelle zur Prüfung vorgelegen. Wörtlich übernommene Textstellen, auch Einzelsätze oder Teile davon, sind als Zitate kenntlich gemacht worden. Hierdurch erkläre ich, dass ich die „Leitlinien guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis“ der Deutschen Sporthochschule Köln eingehalten habe. Köln, 18. Dezember 2012 ________________ (Yi-Ling Huang) Danksagung Für meine Doktorarbeit schulde ich sehr vielen Menschen einen herzlichen Dank. Besonders möchte ich mich bei meinem Doktorvater, Herrn Prof. Dr. Manfred LÄMMER bedanken, denn Sie brachten mir sehr viel Geduld entgegen, opferten viele Ihre freien Abend und sorgten mit wertvollen Empfehlungen für den Erfolg dieser Arbeit. Des Weiteren möchte ich mich bei Herrn Prof. Dr. CHENG Jui-fu und Herrn Prof. Dr. HSU Yi-hsiung bedanken, denn ohne ihre Anregungen wäre ich nie auf die Idee gekommen in Deutschland zu studieren. Das Leben in Deutschland ist für Ausländer nicht einfach, daher möchte ich mich bei Claudia MENTEN, Rebecca SCHAFFELD, Herbert HEMSING und PENG Li bedanken. Ohne ihre Hilfe könnte mein Leben in Deutschland nicht so reibungslos verlaufen. -

26Thps 2019.Pdf

26thPS_2019.indd 1 3/11/2020 10:37:05 26thPS_2019.indd 2 3/11/2020 10:37:05 Olympic Studies 26th INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON OLYMPIC STUDIES FOR POSTGRADUATE STUDENTS 26thPS_2019.indd 3 3/11/2020 10:37:05 Published by the International Olympic Academy Athens, 2020 International Olympic Academy 52, Dimitrios Vikelas Avenue 152 33 Halandri – Athens GREECE Tel.: +30 210 6878809-13, +30 210 6878888 Fax: +30 210 6878840 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ioa.org.gr Editor: Konstantinos Georgiadis Editorial coordination: Roula Vathi Photographs: IOA Photographic Archives ISBN: 978-960-9454-53-7 ISSN: 2654-1343 26thPS_2019.indd 4 3/11/2020 10:37:05 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY Olympic Studies 26th INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON OLYMPIC STUDIES FOR POSTGRADUATE STUDENTS 8–30 MAY 2019 Editor KONSTANTINOS GEORGIADIS Professor, University of Peloponnese Honorary Dean of the IOA ANCIENT OLYMPIA 26thPS_2019.indd 5 3/11/2020 10:37:05 26thPS_2019.indd 6 3/11/2020 10:37:05 EPHORIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY (2019) President Isidoros KOUVELOS (HOC Member) Vice-President Michael FYSENTZIDIS (HOC Member) Members Spyros CAPRALOS (HOC President – ex officio member) Emmanuel KOLYMPADIS (HOC Secretary General – ex officio member) Emmanuel KATSIADAKIS (HOC Member) Georgios KARABETSOS (HOC Member) Athanasios KANELLOPOULOS (HOC Member) Efthimios KOTZAS (Mayor, Ancient Olympia) Gordon TANG Honorary President Jacques ROGGE (IOC Honorary President) Honorary Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS (Professor, University of Peloponnese) Honorary Members Pere MIRÓ (IOC Deputy Director General for Relations with the Olympic Movement) Makis MATSAS 7 26thPS_2019.indd 7 3/11/2020 10:37:05 IOC COMMISSION FOR OLYMPIC EDUCATION (2019) Chair Mikaela COJUANGCO JAWORSKI Members Beatrice ALLEN Nita AMBANI Seung-min RYU Paul K. -

“Where the World's Best Athletes Compete”

6 0 T H A N N U A L “Where the world’s best athletes compete” MEDIA INFORMATION updated on April 5, 2018 6 0 T H A N N U A L “Where the world’s best athletes compete” MEDIA INFORMATION April 5, 2018 Dear Colleagues: The 60th Annual Mt. SAC Relays is set for April 19, 20 and 21, 2018 at Murdock Stadium, on the campus of El Camino College in Torrance, CA. Once again we expect over 5,000 high school, masters, community college, university and other champions from across the globe to participate. We look forward to your attendance. Due to security reasons, ALL MEDIA CREDENTIALS and Parking Permits will be held at the Credential Pick-up area in Parking Lot D, located off of Manhattan Beach Blvd. (please see attached map). Media Credentials and Parking Permit will be available for pick up on: Thursday, April 19 from 2pm - 8pm Friday, April 20 from 8am - 8pm Saturday, April 21 from 8am - 2pm Please present a photo ID to pick up your credentials and then park in lot C which is adjacent to the media credential pick up. Please remember to place your parking pass in your window prior to entering the stadium. The Mt. SAC Relays provides the following services for members of the media: Access to press box, infield and media interview area Access to copies of official results as they become available Complimentary food and beverage for all working media April 20 & 21 WiFi access Additional information including time schedules, dates, times and other important information can be accessed via our website at http://www.mtsacrelays.com If you have any additional questions or concerns, please feel free to call or e-mail me at anytime. -

World Rankings — Women's

World Rankings — Women’s 100 © GIANCARLO COLOMBO/PHOTO RUN The ’08 Olympic gold led to the first of Shelly-Ann Fraser- Pryce’s 5 No. 1s in a 12-year span 1956 1957 1 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 1 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 2 ........ Christa Stubnick (East Germany) 2 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 3 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 3 ...............Vera Krepkina (Soviet Union) 4 ..............Galina Popova (Soviet Union) 4 ...........Hannie Bloemhof (Netherlands) 5 .............................Isabelle Daniels (US) 5 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 6 ...................... Giuseppina Leone (Italy) 6 ..............Galina Popova (Soviet Union) 7 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 7 .......................... Erica Willis (Australia) 8 ......................June Paul (Great Britain) 8 .....Brunhilde Hendrix (West Germany) 9 ..............Heather Young (Great Britain) 9 .........................Fleur Mellor (Australia) 10 ..... Galina Rezchikova (Soviet Union) 10 ..........Madeleine Cobb (Great Britain) © Track & Field News 2020 — 1 — World Rankings — Women’s 100 1958 1962 1 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 1 ............ Dorothy Hyman (Great Britain) 2 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 2 ..............................Wilma Rudolph (US) 3 ...............................Barbara Jones (US) 3 ................ Jutta Heine (West Germany) 4 ..............Heather Young (Great Britain) 4 ..........................Teresa Ciepła (Poland) 5 -

Multiple Margins: Sport, Gender and Nationalism in Taiwan Ying Chiang

Multiple Margins: Sport, Gender and Nationalism in Taiwan Ying Chiang (Chihlee Institute of Technology, Taiwan), Alan Bairner (Loughborough University, UK), Dong-jhy Hwang (National Taiwan Sport University) and Tzu-hsuan Chen (National Taiwan Sport University) * * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Abstract This article aims to build contextualised and cross-cultural understandings of gender discourses on sport and nationalism. With its multi-colonised history and its multi-ethnic groups, modern Taiwan has a very different ‘national’ story from most western societies. The way that sport is articulated with Taiwanese nationalism is also unique. With the Taiwanese being desperate for every chance to prove their existence and worth, sport becomes an important field for constructing national honour and identity. When sports women succeed on the international stage, especially when their male counterparts fail, the discourse on women, sport and nationalism becomes unusual. In sum, the unique character of Taiwanese sport nationalism creates empowerment opportunities for female athletes. But, we should bear in mind that men still take the dominant roles in Taiwan’s sport field. Gendered disciplinary discourses, such as the beauty myth and compulsory heterosexuality, still dominate Taiwanese female athletes’ media representation and further influence their practice and self-identity. Keywords: sport nationalism; Taiwan; gender; Beijing Olympics 1 Introduction In contemporary western cultural discourses, nationalism and national identity consistently provoke controversy. Furthermore, a significant amount of research has focused on the relationship between sport and the construction and transformation of nationalism and national identity, with some research suggesting that sport stimulates patriotism, builds national identity and, in certain circumstances, leads to conflict. -

2016 US OLYMPIC TEAM WOMEN Heptathlon

2016 US OLYMPIC TEAM WOMEN’S HEPTATHLON TRIALS and th 36 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS Hayward Field University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon July 9-10, 2016 Frank Zarnowski DECA, The Decathlon Association www.decathlonusa.typepad.com Table of Contents Sectio n One: Background Information page 2 Time Schedule 2 Qualifying Procedures 2 List of Qualifiers 3 Web sites which will post results 4 Section Two: Record Section US Olympic Trials Winners-1964-2012 4 USA National Champions- 1950-2015 5 Adenda 6 Individual Event Records 6 Recent Meet results:[USOT’08,’12, USA’13-‘15] 7 All-Time USA Heptathlon List 9 PR Page 10 Section Three: Athlete’s Bios 11-32 Bougard, Erica 11 Brooks, Taliyah 12 Chapman, Quituna 13 Day-Monroe, Sharon 14 Flax, Jessica 16 Gochenour, Alex 17 Kunz, Annie 18 Lehman, Jess 19 Lettow, Lindsay 20 McMillan, Chantae 21 Miller-Koch, Heather 22 Nwaba, Barbara 23 Profit, Kiani 24 Reaser, Allison 25 Schwartz, Lindsay 26 Spenner, Sami 27 Stumbaugh, Payton 28 Williams, Kendell 29 Alternates- the 59ers Carrier-Eades, Chelsea 30 Hawkins, Chari 31 Leslie, Breanna 32 Parker, Tiffeny 33 Souza, Tatum 34 Page 1 SECTION ONE: Basic Info: a) Time Schedule b) Qualifying procedures c) List of Qualifiers d) Web sites which will provide results a… Time Schedule Saturday, July 9, 2016 Sunday, Julu 10, 2016 12:30 pm 100 m Hurdles 1:45 pm Long Jump 1:30 High Jump 2:45 Javelin 3:30 Shot Put 4:11 800 meters 4:40 200 meters b) …..Qualifying Procedure -The standard is 6150, (previously announced and remained 5900 until mid-May, 2016). -

Depot Park Development, Award Made News in 2013

40 percent chance of snow High: 8 | Low: -2 | Details, page 2 Passion for excellence. Compassion for people. aspirusgrandview.org GV-013a DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Thursday, December 26, 2013 75 cents B I R D C O U N T Photo submitted by Kim Herman BLUE JAYS placed fourth this year in the Bessemer Area Bird Count. Rare duck shows up in Christmas Bird Count By JERRY EDDE really, because other than some special to The Daily Globe rapids on local streams and rivers, I was still fiddling with the and the little patch of water I was focus knob on the spotting scope looking at, there is no open water when the duck flipped up and dove during late December within 7.5 for the bottom of the pond. miles of Bessemer, the scope of the “Uh oh, that’s no mallard,” I range for the Christmas Bird thought, as I struggled to bring Count. the edge between the open water Earlier Saturday, we had just and the snow-covered ice into turned onto East Norrie Park Cortney Ofstad/Daily Globe sharp focus. Road when Christy said, “There’s JIM RADY, of Ironwood, receives a helping of ham from volunteer Jerry Wanink at Woodland Church, during a free Christmas meal, Wednes- Through the binoculars, it a blue jay.” And just as I was day in Ironwood. appeared the duck out on the about to say, “Two blue jays,” Bessemer Area Wastewater Treat- Christy shouted, “Wow, there’s ment pond might be a mallard, something big. It’s an Ee—Ee— but it was really too far to tell at Ee—.” Woodland Church offers annual 10 power. -

World Rankings — Women’S 100H (Note: from ’56 Through ’68 the Ranked 1957 Distance Was 80 Meters) 1

World Rankings — Women’s 100H (note: from ’56 through ’68 the ranked 1957 distance was 80 meters) 1 ............ Nelli Yelisayeva (Soviet Union) 2 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 3 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 1956 4 .....Maria Golubnichaya (Soviet Union) 1 ............. Shirley de la Hunty (Australia) 5 .................Erika Fisch (West Germany) 2 ................ Zenta Kopp (West Germany) 6 ................ Zenta Kopp (West Germany) 3 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 7 ...... Edeltraud Eiberle (West Germany) 4 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 8 ..................... Gloria Wigney (Australia) 5 .....Maria Golubnichaya (Soviet Union) 9 .........................Betty Moore (Australia) 6 ...................Norma Thrower (Australia) 10 ...............................Elaine Winter (US) 7 .........Nina Vinogradova (Soviet Union) 8 .................Erika Fisch (West Germany) Keni Harrison didn’t make it to 9 ..................... Gloria Wigney (Australia) Rio, but was 2016’s No. 1 after 10 ........... Maria Sander (West Germany) her World Record. © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN © Track & Field News 2020 — 1 — World Rankings — Women’s 100H 1958 1962 1 ............Galina Bystrova (Soviet Union) 1 .........................Betty Moore (Australia) 2 ................ Zenta Kopp (West Germany) 2 ............................Pam Ryan (Australia) 3 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 3 ..........................Teresa Ciepła (Poland) 4 ...................Norma Thrower (Australia) 4 .................Erika -

The IOC and the China Issue at the 1976 Montreal Olympic Games

Side-Swiped: the IOC and the China Issue at the 1976 Montreal Olympic Games By Richard W. Pound | Part 2 The IOC Session in Montreal Opening of the 78th The IOC Session in Montreal began on 13 July 1976, in Session at Place des the midst of the various and daily discussions at the Arts: Lord Killanin Executive Board and efforts to negotiate with the addresses the government of Canada and the Republic of China audience at the delegation. By this time as well, the prospect of a podium of the boycott was also a very real possibility. Several delega- Montréal Symphony tions from Africa and other nations were threatening Orchestra (right). to stay away from the Games in protest against a New Zealand rugby tour of South Africa. Sessions of the IOC are particularly unwieldy as a forum for discussion and solution of complex problems, especially those when the the factual context may be constantly changing and rules were involved in the question, one of which was where there is a dramatically uneven level of know- the rule enabling a change of name of the Republic of ledge among the IOC Members. Killanin was at pains China, requiring a two-thirds majority vote, and that to explain the situation, as well as the various actions it would be wrong to do this in retaliation against the taken by the Executive Board to find solutions to the Canadian government’s "dishonesty". He suggested in- China problem.1 It was nevertheless apparent that many forming Prime Minister Trudeau that his government’s of the IOC Members were inclined to be much firmer decision had seriously embarrassed the IOC, and than the Executive Board had been in the circumstan- inviting him and all members of his political party in ces and Killanin, however defensive he may have been Parliament to excuse themselves from the Olympic sites about the choices he had made and those made by the and social functions connected with the Games. -

World Rankings — Women's

World Rankings — Women’s 200 © VICTOR SAILER/PHOTO RUN Dafne Schippers & Elaine Thompson were the No. 1s of ’15 & ’16 1956 1957 1 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 1 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 2 ........ Christa Stubnick (East Germany) 2 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 3 ................... Maria Itkina (Soviet Union) 3 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 4 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 4 ................... Maria Itkina (Soviet Union) 5 ......................June Paul (Great Britain) 5 ........................Nancy Boyle (Australia) 6 ..................... Norma Croker (Australia) 6 ........ Albina Kobranova (Soviet Union) 7 .....................Barbara Sobotta (Poland) 7 ...........Hannie Bloemhof (Netherlands) 8 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 8 ..............Heather Young (Great Britain) 9 ..................Vera Yugova (Soviet Union) 9 .....................Barbara Sobotta (Poland) 10 ...............Jean Scriven (Great Britain) 10 ............Galina Popova (Soviet Union) © Track & Field News 2020 — 1 — World Rankings — Women’s 200 1958 1962 1 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 1 ................ Jutta Heine (West Germany) 2 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 2 ............ Dorothy Hyman (Great Britain) 3 ..............Heather Young (Great Britain) 3 .................................Vivian Brown (US) 4 ........ Christa Stubnick (East Germany) 4 .....................Barbara Sobotta (Poland) 5 ......................June Paul (Great Britain) -

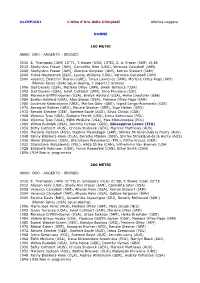

Argento - Bronzo

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera DONNE 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E. Thompson (JAM) 10”71, T. Bowie (USA) 10”83, S. A. Fraser (JAM) 10,86 2012 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Carmelita Jeter (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2008 Shelly-Ann Fraser (JAM), Sherone Simpson (JAM), Kerron Stewart (JAM) 2004 Yuliva Nesterenko (BLR), Lauryn Williams (USA), Veronica Campbell (JAM) 2000 vacante, Ekaterini Thanou (GRE), Tanya Lawrence (JAM), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) (Marion Jones (USA) squal.doping, 2 argenti 1 bronzo) 1996 Gail Devers (USA), Merlene Ottey (JAM), Gwen Torrence (USA) 1992 Gail Devers (USA), Juliet Cuthbert (JAM), Irina Privalova (CSI) 1988 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA), Evelyn Ashford (USA), Heike Drechsler (GEE) 1984 Evelyn Ashford (USA), Alice Brown (USA), Merlene Ottey-Page (JAM) 1980 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (URS), Marlies Göhr (GEE), Ingrid Lange-Auerswald (GEE) 1976 Annegret Richter (GEO), Renate Stecher (GEE), Inge Helten (GEO) 1972 Renate Stecher (GEE), Raelene Boyle (AUS), Silvia Chivás (CUB) 1968 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Barbara Ferrell (USA), Irena Szewinska (POL) 1964 Wyomia Tyus (USA), Edith McGuire (USA), Ewa Klobukowska (POL) 1960 Wilma Rudolph (USA), Dorothy Hyman (GBR), Giuseppina Leone (ITA) 1956 Betty Cuthbert (AUS), Christa Stubnick (GER), Marlene Matthews (AUS) 1952 Marjorie Jackson (AUS), Daphne Hasenjäger (SAF), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1948 Fanny Blankers-Koen (OLA), Dorothy Manley (GBR), Shirley Strickland-de la Hunty (AUS) 1936 Helen Stephens (USA), Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Käthe Krauss (GER) 1932 Stanislawa Walasiewicz (POL), Hilda Strike (CAN), Wilhelmina Van Bremen (USA 1928 Elizabeth Robinson (USA), Fanny Rosenfeld (CAN), Ethel Smith (CAN) 1896-1924 Non in programma 200 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 E. -

Invitational Men 100M

MT. SAC RELAYS - PAST CHAMPIONS - UPDATED AT April 1, 2012 INV MEN 100 METERS 1997 Oumar Loum Senegal 20.60 1973 Fernan. De La Cerda UTEP 1:52.2y 1959 Ray Norton San Jose St 9.5y 1998 Maurice Greene Nike 20.03 1974 Byron Dyce Florida TC 1:49.8y 1960 Ray Norton San Jose St 10.2 1999 Ato Boldon Trinidad 20.19 1975 Bob Martin Club Northwest 1:52.6y 1961 Dennis Johnson San Jose St 9.2yw 2000 Christopher Williams Jamaica 20.02 1976 Rick Brown Bev Hills Striders 1:50.09y 1962 Henry Carr Arizona St 9.5y 2001 Ato Boldon Trinidad 20.76 1977 Mike Boit Kenya 1:47.77 1963 Bob Hayes Florida A&M 9.9w 2002 Floyd Heard Unat 20.31 1979 Steve Scott UC Irvine 1:47.9 1964 Darel Newman Fresno St 10.lw 2003 Maurice Greene adidas 20.16 1980 Mike Boit Kenya 1:46.19 1965 Pablo McNeil SC Astros 9.4yw 2004 Mickey Grimes HSI 20.31 1981 James Robinson Inner City AC 1:48.42 1966 Lennox Miller USC 10.3 2005 Wallace Spearmon Arkansas 19.97 1982 Sammy Koskei SMU 1:45.26 1967 Menzies Campbell Athens Sports 10.2w 2006 LaShawn Merritt Nike 20.23 1983 Sammy Koskei Nike 1:46.08 1968 Mel Pender US Army 10.3 2007 Mike Mitchell South Bay TC 20.33 1984 Agberto Guimares Brazil 1:47.45 1969 John Carlos San Jose St 9.2y 2008 Chris Berman Velocity 9 20.43w 1985 James Robinson Inner City AC 1:47.41 1970 Kirk Clayton San Jose St 10.2 2009 Lionel Larry adidas 20.37 1986 William Wuyke New Balance TC 1:48.4 1971 Chuck Smith California TC 9.3yw 2010 Rubin Williams Heritage Elite 20.49w 1987 Randy Moore New York AC 1:47.61 1972 JL Ravelomanantsoa Westmont 10.lw 2011 Greg Nixon High Perfornance