A Comparison of Spatial Referencing in Native French Speakers from Four Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beschluss Der FIBAA-Akkreditierungskommission Für Programme

Beschluss der FIBAA-Akkreditierungskommission für Programme 83. Sitzung am 27./28. September 2012 89. Sitzung am 28./29. November 2013: Projektnummer: 13/017 (siehe auch Bericht ab S. 61.) 106. Sitzung am 23. März 2018: Projektnummer: 17/138 (siehe auch Bericht ab S. 77.) 11/069 Fachhochschule der Wirtschaft (FHDW) Paderborn, Bielefeld, Bergisch Gladbach, Mettmann Wirtschaftsinformatik (B.Sc.) Die FIBAA-Akkreditierungskommission für Programme beschließt im Auftrag der Stiftung zur Akkreditierung von Studiengängen in Deutschland wie folgt: Der Studiengang Wirtschaftsinformatik (B.Sc.) wird gemäß Abs. 3.1.1 i.V.m. 3.2.1 der Regeln des Akkreditierungsrates für die Akkreditierung von Studiengängen und für die Systemak- kreditierung i.d.F. vom 07. Dezember 2011 für sieben Jahre re-akkreditiert. Das Siegel des Akkreditierungsrates und das Qualitätssiegel der FIBAA werden verliehen. Akkreditierungszeitraum: 28. September 2012 bis Ende WS 2019 FOUNDATION FOR INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION ACCREDITATION FIBAA – BERLINER FREIHEIT 20-24 – D-53111 BONN Gutachterbericht Hochschule: Fachhochschule der Wirtschaft (FHDW) Paderborn, Bielefeld, Bergisch Gladbach, Mettmann Bachelor-Studiengang: Wirtschaftsinformatik Abschlussgrad: Bachelor of Science (B.Sc.) Kurzbeschreibung des Studienganges: Der Studiengang vermittelt Kenntnisse und Fähigkeiten, die erforderlich sind, um im Informa- tikbereich von Unternehmen und Organisationen erfolgreich tätig sein zu können. Die Studie- renden erwerben außerdem Grundkenntnisse in Mathematik und Betriebswirtschaft und Kenntnisse in Englisch und sollen zur Anwendung wissenschaftlicher Erkenntnisse und Me- thoden sowie zu verantwortlichem Handeln befähigt werden. Durch die ebenfalls zu erwer- benden Schlüsselqualifikationen (Fähigkeiten zur Kommunikation und Präsentation, zur Selbstorganisation und zum Zeitmanagement sowie Teamfähigkeit) sollen sie sich zusätzlich für die berufliche Praxis qualifizieren. Datum der Verfahrenseröffnung: 29. Juli 2011 Datum der Einreichung der Unterlagen: 14. -

Sister Cities Programs

Szczecin, Poland Sister Cities Programs Porta Westfalica, Germany Paderborn, Germany Gross-Bieberau, Germany Marbach, Germany Ludwigsburg, Germany Stuttgart, Germany February 2011 Sursee, Switzerland Brcko, Bosnia-Herzegovina Greenland Lyon, France 0 200 400 Miles Bologna, Italy Finland Russia Canada Donegal, Ireland Samara, Russia Galway, Ireland Ukraine Kazakhstan Mongolia Spain Turkey United States China Iraq Iran Suwa, Japan Algeria San Luis Potosi, Mexico Libya Egypt Mexico Saudi Arabia Nanjing, China India Mauritania Wuhan, China St. Louis, Senegal Mali Niger Chad Sudan Georgetown, Guyana Nigeria Venezuela Ethiopia Colombia Highland Kenya Congo, DRC Bogor, Indonesia Tanzania Peru Brazil St. Charles Angola Zambia St. Louis Bolivia Belleville Namibia Millstadt Australia Washington Waterloo Argentina 0 5 10 20 St. Louis/St. Louis County Miles Sister Cities Bologna, Italy Bogor, Indonesia Belleville Brcka, Bosnia-Herzegovina Paderborn, Germany Donegal County, Ireland Highland Galway, Ireland Sister Cities is a city-to-city network inspired by President Dwight D. Eisenhower's suggestion Sursee, Switzerland Georgetown, Guyana in 1956 that citizen diplomacy might reduce the chance of future world conflict. Today, more Millstadt Lyon, France than 900 U.S. cities are paired with 1,300 cities in 92 different countries. Benefits of participation include: Gross-Bieberau, Germany Nanjing, China * International business contacts St. Charles St. Louis, Senegal * Increased awareness of other cultures Ludwigsburg, Germany Samara, Russia I * Opportunities to become host families for visitors and students from abroad Washington Stuttgart, Germany * Volunteer and community service Marbach, Germany Suwa, Japan Sources: East-West Gateway * Fostering of mutually beneficial relations in economic development, education, art, culture, medicine, and sports Waterloo Szczecin, Poland Council of Governments; Sister Cities International; * Showcase St. -

Factor Graph Decoding for Speech Presence Probability Estimation

ITG-Fachbericht 267: Speech Communication · 05. – 07.10.2016 in Paderborn Factor Graph Decoding for Speech Presence Probability Estimation Thomas Glarner, Mohammad Mahdi Momenzadeh, Lukas Drude, Reinhold Haeb-Umbach Department of Communications Engineering, Paderborn University, 33098 Paderborn, Germany Email: {glarner,drude,haeb}@nt.uni-paderborn.de Web: nt.uni-paderborn.de Abstract ing an MMSE estimator for the spectral amplitude [9], they are employed here for SPP estimation for the first time. This paper is concerned with speech presence probability Second, viewing the aforementioned turbo algorithm as a estimation employing an explicit model of the temporal particular message passing scheme for inference in graph- and spectral correlations of speech. An undirected graphi- ical models with loops, alternative schemes will be inves- cal model is introduced, based on a Factor Graph formula- tigated, thus introducing general factor graph decoding as tion. It is shown that this undirected model cures some an approach to SPP estimation. of the theoretical issues of an earlier directed graphical The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In model. Furthermore, we formulate a message passing in- Section 2, the signal model is presented, and the SPP es- ference scheme based on an approximate graph factoriza- timation problem is formulated. Section 3 introduces the tion, identify this inference scheme as a particular message UGM, a Factor Graph formulation and the inference algo- passing schedule based on the turbo principle and suggest rithm. The UGM is contrasted with the Directed Graphical further alternative schedules. The experiments show an im- Model of [7] in Section 4, giving reasons why the UGM proved performance over speech presence probability esti- is to be preferred. -

The Berlin Group and the Philosophy of Logical Empiricism BOSTON STUDIES in the PHILOSOPHY and HISTORY of SCIENCE

The Berlin Group and the Philosophy of Logical Empiricism BOSTON STUDIES IN THE PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY OF SCIENCE Editors ROBERT S. COHEN, Boston University JURGEN¨ RENN, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science KOSTAS GAVROGLU, University of Athens Managing Editor LINDY DIVARCI, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Editorial Board THEODORE ARABATZIS, University of Athens ALISA BOKULICH, Boston University HEATHER E. DOUGLAS, University of Pittsburgh JEAN GAYON, Universit´eParis1 THOMAS F. GLICK, Boston University HUBERT GOENNER, University of Goettingen JOHN HEILBRON, University of California, Berkeley DIANA KORMOS-BUCHWALD, California Institute of Technology CHRISTOPH LEHNER, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PETER MCLAUGHLIN, Universit¨at Heidelberg AGUSTI´ NIETO-GALAN, Universitat Aut`onoma de Barcelona NUCCIO ORDINE, Universit´a della Calabria ANA SIMOES,˜ Universidade de Lisboa JOHN J. STACHEL, Boston University SYLVAN S. SCHWEBER, Harvard University BAICHUN ZHANG, Chinese Academy of Science VOLUME 273 For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/5710 Nikolay Milkov • Volker Peckhaus Editors The Berlin Group and the Philosophy of Logical Empiricism 123 Editors Nikolay Milkov Volker Peckhaus Department of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Paderborn University of Paderborn 33098 Paderborn 33098 Paderborn Germany Germany ISSN 0068-0346 ISBN 978-94-007-5484-3 ISBN 978-94-007-5485-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-5485-0 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress -

Misconceptions in Physics Explainer Videos and the Illusion Of

Running head: MISCONCEPTIONS IN EXPLAINER VIDEOS 1 When Learners Prefer the Wrong Explanation: Misconceptions in Physics Explainer Videos and the Illusion of Understanding Christoph Kulgemeyer*a University of Paderborn Jörg Wittwerb University of Freiburg *a Corresponding author. Physics Education, Department of Physics, University of Paderborn, Germany, Warburger Str. 100, 33098 Paderborn, Germany, E-mail: [email protected]. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6659-8170 bDepartment of Educational Science, University of Freiburg, Germany, Rempartstr. 11, 79098 Freiburg, Germany, E-mail: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000- 0001-9984-7479 2 MISCONCEPTIONS IN EXPLAINER VIDEOS Abstract Online explanation videos on platforms like YouTube are popular among students and serve as an important resource for both distance learning and regular science education. Despite their immense potential, some of the explainer videos for physics include problematic explanation approaches, possibly fostering misconceptions. However, some of them manage to achieve good ratings on YouTube. A possible reason could be that explainer videos with misconceptions foster an “illusion of understanding”—the mistaken belief that a topic has been understood. In particular, misconceptions close to everyday experiences might elicit greater interest and appear more convincing than scientifically correct explanations. This experimental study was conducted to research this effect. Physics learners (N = 149), with a low prior knowledge enrolled in introductory university courses on primary education, were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups. While the experimental group watched a video introducing the concept of force relying on misconceptions, the control group watched the scientifically correct video. Both videos were comparable in terms of comprehensibility and duration. -

List of European Companies of the BENTELER Group 1. Austria 1.1

List of European companies of the BENTELER Group 1. Austria 1.1. Benteler International Aktiengesellschaft Schillerstraße 25-27, 5020 Salzburg 1.2. Benteler International Beteiligungs GmbH Schillerstraße 25-27, 5020 Salzburg 1.3. Benteler Distribution Austria GmbH Siegfried-Marcus-Straße 8, A-2362 Biedermannsdorf 2. Belgium 2.1. Benteler Automotive Belgium N.V Mai Zetterlingstraat 70, 9042 Gent 3. Czech Repbulic 3.1. BENTELER Automotive Klásterec s.r.o. Skolní 713, 463 31 Chrastava 3.2. Benteler Automotive Rumburk s.r.o. Bentelerova 460/2, 40801 Rumburk 3.3. Benteler CR s.r.o. Skolni 713, 46331 Chrastava 3.4. Benteler Distribution Czech Republic, spol. s.r.o. Prumyslová 1666, 263 01 Dobríš 3.5. Benteler Maschinenbau CZ s.r.o. Hodkovická 981/42, 46006 Liberec 6 4. Denmark 4.1. Benteler Automotive Tonder A/S Kaergardsvej 5, 6270 Tondern 4.2. Heléns Rör A/S Koesmosevej 48-58, Kauslunde, 5500 Middelfart BENTELER International Aktiengesellschaft 1/6 Schillerstraße 25 | 5020 Salzburg | Austria 5. Estonia 5.1. Benteler Distribution Estonia OÜ Harju maakond, Tule 13, 76501 Saue vald 6. Finland 6.1. Polarputki Oy Hitsaajankatu 9C, 00810 Helsinki 7. France 7.1. Benteler Aluminium Systems France SNC Park Industriel d'Incarville, 27400 Louvièrs 7.2. Benteler Automotive SAS ZI du Moutois, Rue Raymond Poincaré, 89400 Migennes 7.3. Benteler Distribution France S.à.r.l. 15, route de Merville, 27320 La Madeleine de Nonancourt 7.4. Benteler JIT Douai SAS Z.I. du Moutois, Rue Raymond Poincaré, 89400 Migennes 7.5. Benteler Participation S.A. Zone industrielle du Moutois, Rue Raymond Poincaré, 89400 Migennes 8. -

Strain-Dependent Adsorption of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa- Derived Adhesin-Like Peptides at Abiotic Surfaces

micro Article Strain-Dependent Adsorption of Pseudomonas aeruginosa- Derived Adhesin-Like Peptides at Abiotic Surfaces Yu Yang, Sabrina Schwiderek, Guido Grundmeier and Adrian Keller * Technical and Macromolecular Chemistry, Paderborn University, Warburger Str. 100, 33098 Paderborn, Germany; [email protected] (Y.Y.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (G.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Implant-associated infections are an increasingly severe burden on healthcare systems worldwide and many research activities currently focus on inhibiting microbial colonization of biomedically relevant surfaces. To obtain molecular-level understanding of the involved processes and interactions, we investigate the adsorption of synthetic adhesin-like peptide sequences derived from the type IV pili of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains PAK and PAO at abiotic model surfaces, i.e., Au, SiO2, and oxidized Ti. These peptides correspond to the sequences of the receptor-binding domain 128–144 of the major pilin protein, which is known to facilitate P. aeruginosa adhesion at biotic and abiotic surfaces. Using quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (QCM-D), we find that peptide adsorption is material- as well as strain-dependent. At the Au surface, PAO(128–144) shows drastically stronger adsorption than PAK(128–144), whereas adsorption of both peptides is markedly reduced at the oxide surfaces with less drastic differences between the two sequences. These observations suggest that peptide adsorption is influenced by not only the peptide sequence, Citation: Yang, Y.; Schwiderek, S.; but also peptide conformation. Our results furthermore highlight the importance of molecular-level Grundmeier, G.; Keller, A. -

2018 61St Annual German-American Steuben Parade Press

61st Annual German-American Steuben Parade of NYC Saturday, September 15, 2018 PRESS KIT The Parade: German-American Steuben Parade, NYC Parade’s Date: Saturday, September 15, 2018 starting at 12:00 noon Parade Route: 68th Street & Fifth Avenue to 86th Street & Fifth Avenue. General Chairman: Mr. Robert Radske Contacts: Email: [email protected] Phone: Sonia Juran Kulesza 347.495.2595 Grand Marshals: This year we are honored to have Mr. Peter Beyer, Member of the German Bundestag and Coordinator of Transatlantic Cooperation, and Mr. Helmut Jahn, renowned Architect, as our Grand Marshals. Both Mr. Beyer and Mr. Jahn are born in Germany, in Ratingen, North Rhine-Westphalia and Nuremberg, Bavaria respectively. Prior Grand Marshals: Some notable recent Grand Marshals have included: 6th generation member of the Flying Wallendas family – Nik Wallenda; Former Nobel Peace Prize recipient and United States National Security Advisor and Secretary of State of State under President Richard Nixon – Dr. Henry Kissinger; Long Island’s own actress, writer and supermodel - Ms. Carol Alt; beloved NY Yankees owner - Mr. George Steinbrenner; Sex Therapist and media personality - Dr. Ruth Westheimer; CNBC Correspondent – Contessa Brewer. Parade Sponsors: The Official Sponsors of the 61st Annual German-American Steuben Parade are the Max Kade Foundation, New York Turner Verein, The Cannstatter Foundation, The German Society of the City of New York, Dieter Pfisterer, Rossbach International, Wirsching Enterprise, Niche Import Company and Merican Reisen. Participants: The Committee will welcome over 300 participating groups from NY, NJ, CA, CT, IL, MA, MD, PA, TX and WI. In addition, 24 groups from Germany, Austria and Switzerland will attend this year’s Parade, totaling well over 2,000 marchers! Plus, 19 Floats will ride up Fifth Avenue in NYC. -

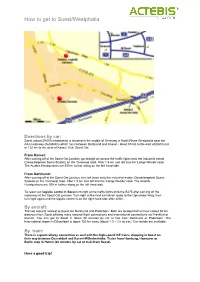

How to Get to Soest/Westphalia

How to get to Soest/Westphalia Directions by car: Soest (about 49,000 inhabitants) is situated in the middle of Germany in North Rhine Westphalia near the A44 motorway (Autobahn) which runs between Dortmund and Kassel - about 50 km to the east of Dortmund or 120 km to the west of Kassel. Exit: Soest Ost. From Kassel: After coming off at the Soest-Ost junction, go straight on across the traffic lights onto the industrial estate (Gewerbegebiet Soest-Südost) on the 'Overweg' road. After 1.5 km turn left into the 'Lange Wende' road. The Actebis Headquaters are 300 m further along on the left hand side. From Dortmund: After coming off at the Soest-Ost junction, turn left twice onto the industrial estate (Gewerbegebiet Soest- Südost) on the 'Overweg' road. After 1,5 km turn left into the 'Lange Wende' road. The Actebis Headquarters are 300 m further along on the left hand side. To reach our logistic centre in Soest turn right at the traffic lights onto the B475 after coming off the motorway at the Soest-Ost junction. Turn right at the next exit which leads to the Opmünder Weg, then turn right again and the logistic centre is on the right hand side after 200m. By aircraft: The two airports nearest to Soest are Dortmund and Paderborn. Both are located half an hour (about 50 km distance) from Soest offering many national flight connections and international connections via Frankfurt or Munich. You can get to Soest in about 30 minutes by car or taxi from Dortmund or Paderborn. -

Basic Itinerary

German Business & Culture + Global Negotiation 2018 – Basic Itinerary Sunday, April 29: Leave USA (or leave early and spend a little extra time in Hamburg at your cost. Many students have done this in past as the Hostel is cheap and the flight costs the same either way) Monday, April 30: Arrive in Hamburg Arrive, stay awake and get settled. We will explore the city center and have a group dinner. Did I mention stay awake! Tuesday, May 1: Harbor Tour & Travel Day + it is a German Holiday (Erste Mai) .Hamburg is Germany’s biggest port and we will take a harbor tour and discuss the history of this economic center of Germany. Late afternoon high speed train to Berlin! Wednesday, May 2: Berlin + Volkswagen World Headquarters Visit Wolfsburg production plant, Branding lecture by Dr. Stefan Hoernemann and visit Autostadt. Experience German rail system in traveling Berlin to Potsdam and back. The production plant tour and the branding lecture are not things typical visitors to VW could experience. Dr. Eckert’s relationship with senior VW personnel create a unique experience. Thursday, May 3: Fat Tire Bike Tour of Berlin Explore the history and culture of Berlin via a full-day Fat Tire Bike Tour covering Berlin history, WWII history and Cold War history. Lunch in Tierpark featuring German specialties Friday, May 4: Uni Potsdam Negotiation Day Visit Uni Potsdam for Negotiation Case Experience with Uni Potsdam students hosted by Dr. Uta Herbst. Full day, case-based experience with lecture and experiential learning. Cross- group (Uni Potsdam + WMU) celebration dinner at conclusion. -

Dendritic Liquid Crystals

Dendritic liquid crystals Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) der Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät II Chemie, Physik und Mathematik der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg vorgelegt von Herrn Gergely Gulyás geb. am 13.07.1977 in Miskolc, Ungarn Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Bernhard Westermann 2. Prof. Dr. László Somsák Halle (Saale), 11. Januar 2018 Acknowledgment This work has been carried out in the Department of Organic Chemistry at the University of Paderborn (2002-2004) and in the Leibniz Institute of Plant Biochemistry, Halle (Saale) (2004- 2007). I am most grateful to Professor Bernhard Westermann for giving me the chance to do the PhD in his research group and for his continuing support throughout the many years. I am thankful to the late Professor Karsten Krohn who was head of the Organic Chemistry Department in Paderborn to allow me to start the work in the Department. I am equally thankful to Professor Ludger Wessjohann for providing me with the chance to continue my work in the Leibniz Institute in Halle (Saale). I am also thankful to Professor József Deli at the Medical School of University of Pécs to allow me to finish the work beside having a position in his Carotenoid Research Group. I am indebted to Professor Carsten Tschierske for the invaluable help of determining the liquid crystalline properties of my compounds. Without him it could have not been possible to terminate the work successfully. I am grateful to Professor László Somsák for taking the burden of acting as -

Battle for the Ruhr: the German Army's Final Defeat in the West" (2006)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Battle for the Ruhr: The rGe man Army's Final Defeat in the West Derek Stephen Zumbro Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Zumbro, Derek Stephen, "Battle for the Ruhr: The German Army's Final Defeat in the West" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2507. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2507 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BATTLE FOR THE RUHR: THE GERMAN ARMY’S FINAL DEFEAT IN THE WEST A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Derek S. Zumbro B.A., University of Southern Mississippi, 1980 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 2001 August 2006 Table of Contents ABSTRACT...............................................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................1