Notes Upon Dancing Historical and Practical by C. Blasis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

L'opera Italiana Nei Territori Boemi Durante Il

L’OPERA ITALIANA NEI TERRITORI BOEMI DURANTE IL SETTECENTO V. 1-18_Vstupy.indd 2 25.8.20 12:46 Demofoonte come soggetto per il dramma per musica: Johann Adolf Hasse ed altri compositori del Settecento a cura di Milada Jonášová e Tomislav Volek ACADEMIA Praga 2020 1-18_Vstupy.indd 3 25.8.20 12:46 Il libro è stato sostenuto con un finanziamento dell’Accademia delle Scienze della Repubblica Ceca. Il convegno «Demofoonte come soggetto per il dramma per musica: Johann Adolf Hasse ed altri compositori del Settecento» è stato sostenuto dall’Istituto della Storia dell’Arte dell’Accademia delle Scienze della Repubblica Ceca con un finanziamento nell’ambito del programma «Collaborazione tra le Regioni e gli Istituti dell’Accademia delle Scienze della Repubblica Ceca » per l’anno 2019. Altra importante donazione ha ricevuto l’Istituto della Storia dell’Arte dell’Accademia delle Scienze della Repubblica Ceca da Johann Adolf Hasse-Gesellschaft a Bergedorf e.V. Prossimo volume della collana: L’opera italiana – tra l’originale e il pasticcio In copertina: Pietro Metastasio, Il Demofoonte, atto II, scena 9 „Vieni, mia vita, vieni, sei salva“, Herissant, vol. 1, Paris 1780. In antiporta: Il Demofoonte, atto II, scena 5 „Il ferro, il fuoco“, in: Opere di Pietro Metastasio, Pietro Antonio Novelli (disegnatore), Pellegrino De Col (incisore), vol. 4, Venezia: Antonio Zatta, 1781. Recensori: Prof. Dr. Lorenzo Bianconi Prof. Dr. Jürgen Maehder Traduzione della prefazione: Kamila Hálová Traduzione dei saggi di Tomislav Volek e di Milada Jonášová: Ivan Dramlitsch -

Medicine We Know It’S Good to Meditate, but We’Ve Overlooked the Healing Power of Ecstatic Shaking

SHAKING MEDICINE WE KNOW IT’S GOOD TO MEDITATE, BUT WE’ve oVERLOOKED THE HEALING POWER OF ECSTATIC SHAKING . UNTIL NOW. By Bradford Keeney n November of 1881, a Squaxin Indian log- ger from Puget Sound named John Slocum became sick and soon was pronounced dead. As he lay covered with sheets, friends proceeded to conduct a wake and wait for Ihis wooden coffin to arrive. To everyone’s aston- ishment, he revived and began to describe an encounter he’d had with an angel. The angel told Slocum that God was going to send a new kind of medicine to the Indian people, which would enable them not only to heal others, but to heal themselves without a shaman or a doctor. This article is adapted from Shaking Medicine: The Healing Power of Ecstatic Movement, © 2007 by Bradford Keeney. Reprinted with permission of Destiny Books (InnerTraditions.com). Photography by Chip Simons 44 SpiritUALitY & HEALth / May~June 2007 / SpiritualityHealth.com About a year later, John Slocum became sick again. This t wasn’t long ago that the practices of yoga, medita- time, his wife, Mary, was overcome with despair. When she ran tion, and acupuncture were relatively unknown. But outside to pray and refresh her face with creek water, she felt today the idea that relaxation and stillness bring forth something enter her from above and flow inside her body. “It healing is a paradigm that Herbert Benson, M.D., felt hot,” she recalled, and her body began to tremble and shake. of Harvard Medical School named the relaxation When she ran back into the house, she spontaneously touched response. -

The Kapralova Society Journal Fall 2018

Volume 16, Issue 2 The Kapralova Society Journal Fall 2018 A Journal of Women in Music Three Nineteenth Century Composers of Salon Music: Léonie Tonel, Maddalena Croff, Elisa Bosch Tom Moore The name of LÉONIE TONEL is forgotten were highly-regarded horticulturists, origi- today, but in the nineteenth century, despite nally from Gand (Ghent). Jean-Baptiste Tonel, her foreign origins, she made a significant born in Gand in 1819, traveled to Mexico in career in Paris as pianist and composer of sa- 1845 (other sources say about 1846), appar- lon music, producing a long catalogue of ently joining an unnamed older brother, and works for piano, published not only in France was followed by family members Auguste and Germany, but even in New York City. Tonel in 1850 and Constant Tonel in 1852. 3 Tonel’s name does appear in Aaron Cohen’s Tonel is mentioned in the Souvenirs de Voy- International Encyclopedia of Women Com- age 4 of his fellow Belgian J.-J. Coenraets posers ; however, the encyclopedia mentions (where the name is spelled Tonell). According only one of her works (the op. 2, Perles et to an obituary in the Bulletins d’arboricul- Diamans , a mazurka), gives no date of birth or ture ,5 he established his residence in Cordova, death, and describes her only as “19 th -century Vera-Cruz, Mexico (about 110 km inland Special points of interest: French composer”. As will be seen, she is from the port city of Veracruz). He returned to certainly French only by adoption. Belgium numerous times. Most importantly, The nineteenth-century salon Tonel is a very unusual surname. -

Albemarle, NC Results Elite ~ Solo

Albemarle, NC Results Elite ~ Solo ~ 8 & Under PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME KENADIE 1ST NEW GIRL IN TOWN We're Dancin' Musical Theater SHEPERD LOOKIN' GOOD AND FEELIN' 2ND We're Dancin' Jazz NIA PATRICK GORGEOUS 3RD THAT'S RICH We're Dancin' Musical Theater MICHAELA KNAPP Elite ~ Solo ~ 911 PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST HURT We're Dancin' Open ANSLEA CHURCH SAMANTHA 2ND LIGHT THE FIRE We're Dancin' Lyrical FOPPE 3RD NOT FOR THE LIFE OF ME We're Dancin' Musical Theater EMMA KELLY REAGAN 4TH LIFE OF THE PARTY We're Dancin' Lyrical MCDOWELL 5TH I HATE MYSELF We're Dancin' Jazz BELLA VITTORIO AUDREY 6TH THE PRAYER We're Dancin' Lyrical ARMBRUSTER SHERLYN 7TH GLAM We're Dancin' Jazz GUZMAN 8TH JAR OF HEARTS We're Dancin' Lyrical PRIA FENNELL 9TH ROYALS We're Dancin' Contemporary PEYTON YOUNT JENNA 10TH DON'T RAIN ON MY PARADE We're Dancin' Open WASHBURN Elite ~ Solo ~ 1214 PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME 1ST BILLY JEAN We're Dancin' Open RAMONE THOMAS 2ND RUN We're Dancin' Open ALEXA WEIR 3RD FALLEN AWAKE We're Dancin' Lyrical SARAH WHITING 4TH GRACE We're Dancin' Lyrical MOLLY HEDRICK 5TH WORK SONG We're Dancin' Open LALA ORBE 6TH HOT NOTE We're Dancin' Musical Theater OLIVIA ALDRIDGE 7TH HEART CRY We're Dancin' Contemporary MICHAYLA LEWIS 8TH HOLD YOUR HAND We're Dancin' Lyrical LACEE CALVERT SARAH 9TH FIND ME We're Dancin' Lyrical TRUMBORE 10TH HALO We're Dancin' Open DARBY GEROGE Elite ~ Solo ~ 1519 PLACE ROUTINE STUDIO NAME CATEGORY SOLOIST NAME ALLEGRA 1ST KICKS We're Dancin' -

[email protected]

Article Go-go dancing – femininity, individualism and anxiety in the 1960s Gregory, Georgina Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/25183/ Gregory, Georgina ORCID: 0000-0002-7532-7484 (2018) Go-go dancing – femininity, individualism and anxiety in the 1960s. Film, Fashion & Consumption, 7 (2). pp. 165-177. It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/ffc.7.2.165_1 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk 1 Georgina Gregory, School of Humanities and the Social Sciences, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, Lancashire. Email: [email protected] Go-Go Dancing - Femininity, Individualism and Anxiety in the 1960s Key words: dance, 1960s, Go-Go, gender, erotic capital Mainly performed by young women at nightclubs and discotheques, go-go dancing was a high-energy, free-form, dance style of the 1960s. Go-go dancers were employed to entertain crowds and to create a ‘cool’ ambience, wearing very revealing outfits including mini dresses, short fringed skirts, tank tops, tight shorts and calf length boots. -

Romantic Ballet

ROMANTIC BALLET FANNY ELLSLER, 1810 - 1884 SHE ARRIVED ON SCENE IN 1834, VIENNESE BY BIRTH, AND WAS A PASSIONATE DANCER. A RIVALRY BETWEEN TAGLIONI AND HER ENSUED. THE DIRECTOR OF THE PARIS OPERA DELIBERATELY INTRODUCED AND PROMOTED ELLSLER TO COMPETE WITH TAGLIONI. IT WAS GOOD BUSINESS TO PROMOTE RIVALRY. CLAQUES, OR PAID GROUPS WHO APPLAUDED FOR A PARTICULAR PERFORMER, CAME INTO VOGUE. ELLSLER’S MOST FAMOUS DANCE - LA CACHUCHA - A SPANISH CHARACTER NUMBER. IT BECAME AN OVERNIGHT CRAZE. FANNY ELLSLER TAGLIONI VS ELLSLER THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN TALGIONI AND ELLSLER: A. TAGLIONI REPRESENTED SPIRITUALITY 1. NOT MUCH ACTING ABILITY B. ELLSLER EXPRESSED PHYSICAL PASSION 1. CONSIDERABLE ACTING ABILITY THE RIVALRY BETWEEN THE TWO DID NOT CONFINE ITSELF TO WORDS. THERE WAS ACTUAL PHYSICAL VIOLENCE IN THE AUDIENCE! GISELLE THE BALLET, GISELLE, PREMIERED AT THE PARIS OPERA IN JUNE 1841 WITH CARLOTTA GRISI AND LUCIEN PETIPA. GISELLE IS A ROMANTIC CLASSIC. GISELLE WAS DEVELOPED THROUGH THE PROCESS OF COLLABORATION. GISELLE HAS REMAINED IN THE REPERTORY OF COMPANIES ALL OVER THE WORLD SINCE ITS PREMIERE WHILE LA SYLPHIDE FADED AWAY AFTER A FEW YEARS. ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR BALLETS EVER CREATED, GISELLE STICKS CLOSE TO ITS PREMIER IN MUSIC AND CHOREOGRAPHIC OUTLINE. IT DEMANDS THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF TECHNICAL SKILL FROM THE BALLERINA. GISELLE COLLABORATORS THEOPHILE GAUTIER 1811-1872 A POET AND JOURNALIST HAD A DOUBLE INSPIRATION - A BOOK BY HEINRICH HEINE ABOUT GERMAN LITERATURE AND FOLK LEGENDS AND A POEM BY VICTOR HUGO-AND PLANNED A BALLET. VERNOY DE SAINTS-GEORGES, A THEATRICAL WRITER, WROTE THE SCENARIO. ADOLPH ADAM - COMPOSER. THE SCORE CONTAINS MELODIC THEMES OR LEITMOTIFS WHICH ADVANCE THE STORY AND ARE SUITABLE TO THE CHARACTERS. -

The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 29 | 2016 Varia The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini Robert Parker and Scott Scullion Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2399 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2399 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2016 Number of pages: 209-266 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Robert Parker and Scott Scullion, « The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini », Kernos [Online], 29 | 2016, Online since 01 October 2019, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/2399 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2399 This text was automatically generated on 10 December 2020. Kernos The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini 1 The Mysteries of the Goddess of Marmarini Robert Parker and Scott Scullion For help and advice of various kinds we are very grateful to Jim Adams, Sebastian Brock, Mat Carbon, Jim Coulton, Emily Kearns, Sofia Kravaritou, Judith McKenzie, Philomen Probert, Maria Stamatopoulou, and Andreas Willi, and for encouragement to publish in Kernos Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge. Introduction 1 The interest for students of Greek religion of the large opisthographic stele published by J.C. Decourt and A. Tziafalias, with commendable speed, in the last issue of Kernos can scarcely be over-estimated.1 It is datable on palaeographic grounds to the second century BC, perhaps the first half rather than the second,2 and records in detail the rituals and rules governing the sanctuary of a goddess whose name, we believe, is never given. -

European Music Manuscripts Before 1820

EUROPEAN MUSIC MANUSCRIPTS BEFORE 1820 SERIES TWO: FROM THE BIBLIOTECA DA AJUDA, LISBON Section B: 1740 - 1770 Unit Six: Manuscripts, Catalogue No.s 1242 - 2212 Primary Source Media EUROPEAN MUSIC MANUSCRIPTS BEFORE 1820 SERIES TWO: FROM THE BIBLIOTECA DA AJUDA, LISBON Section B: 1740-1770 Unit Six: Manuscripts, Catalogue No.s 1242 - 2212 First published in 2000 by Primary Source Media Primary Source Media is an imprint of the Gale Cengage Learning. Filmed in Portugal from the holdings of The Biblioteca da Ajuda, Lisbon by The Photographic Department of IPPAR. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission. CENGAGE LEARNING LIBRARY PRIMARY SOURCE MEDIA REFERENCE EMEA GALE CENGAGE LEARNING Cheriton House 12 Lunar Drive North Way Woodbridge Andover SP10 5BE Connecticut 06525 United Kingdom USA http://gale.cengage.co.uk/ www.gale.cengage.com CONTENTS Introduction 5 Publisher’s Note 9 Contents of Reels 11 Listing of Manuscripts 15 3 INTRODUCTION The Ajuda Library was established after the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 near the royal palace of the same name to replace the court library which had been destroyed in the earthquake, and from its creation it incorporated many different collections, which were either acquired, donated or in certain cases confiscated, belonging to private owners, members of the royal family or religious institutions. Part of the library holdings followed the royal family to Brazil after 1807 and several of these remained there after the court returned to Portugal in 1822. The printed part of those holdings constituted the basis of the National Library of Rio de Janeiro. -

The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection

• The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection N.B.: The Newberry Library does not own all the libretti listed here. The Library received the collection as it existed at the time of Howard Brown's death in 1993, with some gaps due to the late professor's generosity In loaning books from his personal library to other scholars. Preceding the master inventory of libretti are three lists: List # 1: Libretti that are missing, sorted by catalog number assigned them in the inventory; List #2: Same list of missing libretti as List # 1, but sorted by Brown Libretto Collection (BLC) number; and • List #3: List of libretti in the inventory that have been recataloged by the Newberry Library, and their new catalog numbers. -Alison Hinderliter, Manuscripts and Archives Librarian Feb. 2007 • List #1: • Howard Mayer Brown Libretti NOT found at the Newberry Library Sorted by catalog number 100 BLC 892 L'Angelo di Fuoco [modern program book, 1963-64] 177 BLC 877c Balleto delli Sette Pianeti Celesti rfacsimile 1 226 BLC 869 Camila [facsimile] 248 BLC 900 Carmen [modern program book and libretto 1 25~~ Caterina Cornaro [modern program book] 343 a Creso. Drama per musica [facsimile1 I 447 BLC 888 L 'Erismena [modern program book1 467 BLC 891 Euridice [modern program book, 19651 469 BLC 859 I' Euridice [modern libretto and program book, 1980] 507 BLC 877b ITa Feste di Giunone [facsimile] 516 BLC 870 Les Fetes d'Hebe [modern program book] 576 BLC 864 La Gioconda [Chicago Opera program, 1915] 618 BLC 875 Ifigenia in Tauride [facsimile 1 650 BLC 879 Intermezzi Comici-Musicali -

Matt Archer: Legend (Matt Archer #3) by Kendra C. Highley

Matt Archer: Legend (Matt Archer #3) By Kendra C. Highley Nowadays, it’s difficult to imagine our lives without the Internet as it offers us the easiest way to access the information we are looking for from the comfort of our homes. There is no denial that books are an essential part of life whether you use them for the educational or entertainment purposes. With the help of certain online resources, such as this one, you get an opportunity to download different books and manuals in the most efficient way. Why should you choose to get the books using this site? The answer is quite simple. Firstly, and most importantly, you won’t be able to find such a large selection of different materials anywhere else, including PDF books. Whether you are set on getting an ebook or handbook, the choice is all yours, and there are numerous options for you to select from so that you don’t need to visit another website. Secondly, you will be able to download Matt Archer: Legend (Matt Archer #3) By Kendra C. Highley pdf in just a few minutes, which means that you can spend your time doing something you enjoy. But, the benefits of our book site don’t end just there because if you want to get a certain Matt Archer: Legend (Matt Archer #3), you can download it in txt, DjVu, ePub, PDF formats depending on which one is more suitable for your device. As you can see, downloading Matt Archer: Legend (Matt Archer #3) By Kendra C. Highley pdf or in any other available formats is not a problem with our reliable resource. -

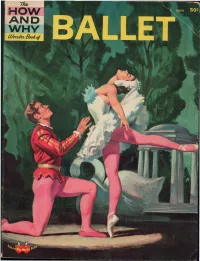

Tfw H O W a N D W H Y U/Orvcfoiboo&O£ • ^Jwhy Wonder W*

Tfw HOW AND • WHY U/orvcfoiBoo&o£ ^JWhy Wonder W* THE HOW AND WHY WONDER BOOK OF B> r Written by LEE WYNDHAM Illustrated by RAFAELLO BUSONI Editorial Production: DONALD D. WOLF Edited under the supervision of Dr. Paul E. Blackwood Washington, D. C. \ Text and illustrations approved by Oakes A. White Brooklyn Children's Museum Brooklyn, New York WONDER BOOKS • NEW YORK Introduction The world had known many forms of the dance when ballet was introduced. But this was a new kind of dance that told a story in movement and pantomime, and over the years, it has become a very highly developed and exciting art form. The more you know about ballet, the more you can enjoy it. It helps to know how finished ballet productions depend on the cooperative efforts of many people — producers, musicians, choreographers, ballet masters, scene designers — in addition to the dancers. It helps to know that ballet is based on a few basic steps and movements with many possible variations. And it helps to know that great individual effort is required to become a successful dancer. Yet one sees that in ballet, too, success has its deep and personal satisfactions. In ballet, the teacher is very important. New ideas and improvements have been introduced by many great ballet teachers. And as you will read here, "A great teacher is like a candle from which many other candles can be lit — so many, in fact, that the whole world can be made brighter." The How and Why Wonder Book of Ballet is itself a teacher, and it will make the world brighter because it throws light on an exciting art form which, year by year, is becoming a more intimate and accepted part of the American scene.