A Semiotic Analysis of Dalit and Non Dalit Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teachers-Of-Private-Colleges

1 Price Rs. 100/- per copy UNIVERSITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate from the Teachers of Private Colleges (Under Section 17 – Elected Members (6) of the Kerala University Act, 1974) ELECTORAL ROLL OF TEACHERS OF PRIVATE COLLEGES-2018 ROLL No. Name Designation College 1. Dr.Caroline Beena Mendez DDO Physics All Saint’s College, Thiruvananthapuram. 2. Sonya J Nair Assistant Professor English ,, 3. Kukku Xavier Assistant Professor ,, ,, 4. Dr.Liji Varghese Assistant Professor ,, ,, 5. Dr.Sr.Pascoela Adelrich Assistant Professor ,, ,, D’Souza 6. Dr.Rajsree M.S Assistant Professor ,, ,, 7. Sapna Srinivas Assistant Professor ,, ,, 8. Simna S Stephen Assistant Professor ,, ,, 9. Nishel Prem Elias Assistant Professor ,, ,, 10. Diana V Prakash Assistant Professor ,, ,, 11. Dr.Kavitha .N Assistant Professor ,, ,, 12. Joveeta Justin Assistant Professor ,, ,, 13. Celina James Assistant Professor ,, ,, 14. Dr.C.Udayakala Assistant Professor Malayalam ,, 15. Parvathy Menon Assistant Professor History ,, 16. Vijayakumari K Assistant Professor ,, ,, 17. Dr.Sreelekha Nair Associate professor Commerce ,, 18. Dr.Reshmi.R.Prasad Associate professor ,, ,, 19. Lissy Bennet Assistant Professor ,, ,, 20. Shirly Joseph Associate professor Mathamatics All Saint’s College, Thiruvananthapuram. 21. Sebina Mathew C Assistant Professor ,, ,, 22. Renjini Raveendran P Assistant Professor ,, ,, 23. Vidhya T.R Assistant Professor ,, ,, 2 24. Dr.Deepa M Associate professor Physics ,, 25. Dr.Anjana P.S Assistant Professor ,, ,, 26. Dr.Veena Suresh Babu Assistant Professor ,, ,, 27. Dr.Sunitha Kurur Assistant Professor Chemistry ,, 28. Dr.Sindhu Yesodharan Assistant Professor ,, ,, 29. Dr.Siji V.L Assistant Professor ,, ,, 30. Dr.Beena Kumari K.S Assistant Professor ,, ,, 31. Dr.Nisha K.K Assistant Professor Botany ,, 32. Dr.Sr.Shaina T J Assistant Professor ,, ,, 33. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies

Asia in Motion: Geographies and Genealogies Organized by With support from from PRIMUS Visual Histories of South Asia Foreword by Christopher Pinney Edited by Annamaria Motrescu-Mayes and Marcus Banks This book wishes to introduce the scholars of South Asian and Indian History to the in-depth evaluation of visual research methods as the research framework for new historical studies. This volume identifies and evaluates the current developments in visual sociology and digital anthropology, relevant to the study of contemporary South Asian constructions of personal and national identities. This is a unique and excellent contribution to the field of South Asian visual studies, art history and cultural analysis. This text takes an interdisciplinary approach while keeping its focus on the visual, on material cultural and on art and aesthetics. – Professor Kamran Asdar Ali, University of Texas at Austin 978-93-86552-44-0 u Royal 8vo u 312 pp. u 2018 u HB u ` 1495 u $ 71.95 u £ 55 Hidden Histories Religion and Reform in South Asia Edited by Syed Akbar Hyder and Manu Bhagavan Dedicated to Gail Minault, a pioneering scholar of women’s history, Islamic Reformation and Urdu Literature, Hidden Histories raises questions on the role of identity in politics and private life, memory and historical archives. Timely and thought provoking, this book will be of interest to all who wish to study how the diverse and plural past have informed our present. Hidden Histories powerfully defines and celebrates a field that has refused to be occluded by majoritarian currents. – Professor Kamala Visweswaran, University of California, San Diego 978-93-86552-84-6 u Royal 8vo u 324 pp. -

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Digital Widescreen | July 2017 Journey into the unknown with KONG: SKULL ISLAND and more thrilling movies Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the 13th consecutive year! NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCJuly17EX2.indd 51 16/06/2017 10:58 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_57_JULY17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 514 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel 2 3 number into your handset, or use WATCH the onscreen channel entry pad 1 3 LIVE TV Swipe left and Search for Move around Live news and sport right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games channels are available Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad on on most fl ights. Find onscreen to and system your handset out more on page 9. scroll features and select using the green 2 4 Create and Tap Settings to game button 4 access your own adjust volume playlist using and brightness Favourites e Boss Baby Many movies are 102 available in up to eight languages. -

List of Digital Theatres for UFO Movies India Ltd

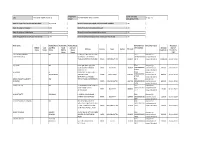

List of Digital Theatres For UFO Movies India Ltd. S.No. THEATRE_CODE THEATRE_NAME ADDRESS1 CITY ACTIVE PAYEE_CODE DISTRICT STATE COMPANY_NAME CMP_CODE SEATING INS_DATE WEB_CODE Main Road, Tagarapuvalasa, Ganesh 1 TH1177 Vizaq, Pin - 531162, Andhra Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 537 9/26/2011 3235 (Tagarapuvalasa) Pradesh Bowdava Road, Vizag, Pin - 2 TH1178 Gokul Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 515 9/26/2011 3244 530004, Andhra Pradesh Main Road, Parvathipuram, Sri Veerabhadra 3 TH1180 Dist-Vijayanagaram, Pin Parvathipuram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 396 9/26/2011 3698 Picture Palace Code - 535501 AP Radhamadhav Chipurupalli, 4 TH1181 Theatre Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 517 9/26/2011 3717 Vijayanagaram (Chipurupalli) 5 TH1182 N.C.S. Theatre A/C Vizianagaram, Pin - 535001 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 577 9/26/2011 2696 Sri Vasavi Kala Main Road, Bobbili, 6 TH1183 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 475 9/26/2011 2700 Mandir (Bobbili) Vizianagaram, Sri Ramanaah 7 TH1184 Theatre Devarapalli, West Godavari Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 371 9/26/2011 2689 (Devarapalli) Main Road, Moidha Sri Satya Theatre 8 TH1185 Junction, Nellimarla, Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 258 9/26/2011 2588 (Nellimarla) Vizianagaram, Pin - 535217 LakshmiLakshmi KKrishnarishna 9 TH1186 Janagoan, Warangal, AP Janagoan Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 747 9/26/2011 832 Deluxe Sri Venkateshwara Main Road, Maripeda - 10 TH1187 Maripeda Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 459 9/26/2011 2653 Theatre 506315, Dist Warangal Main RoadRoad,, MariMaripeda,peda, Dist.-Dist. -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040630 on 2 June 2021. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on September 30, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040630 on 2 June 2021. Downloaded from Audio Visual Alcohol Content in Popular Indian Films Journal: BMJ Open Manuscript ID bmjopen-2020-040630 ArticleFor Type: peerOriginal research review only Date Submitted by the 29-May-2020 Author: Complete List of Authors: Bhagawath, Rohith; Kasturba Medical College Manipal, Community Medicine Kulkarni, Muralidhar; -

Preservation of Culture Through Promotion of Linguistic Cinema In

International Journal of Advanced Mass Communication and Journalism 2020; 1(1): 33-38 E-ISSN: XXXX-XXXX P-ISSN: XXXX- XXXX IJAMCJ 2020; 1(1): 33-38 Preservation of culture through promotion of © 2020 IJAMCJ www.masscomjournal.com linguistic Cinema in India: A critical analysis Received: 08-11-2019 Accepted: 09-12-2019 Dr. Neeraj Karan Singh and Ambar Pandey Dr. Neeraj Karan Singh Faculty of Journalism & Mass Communication, Swami Abstract Vivekenand Subharti In India, cinema is very near to the lives of people or we can say that it is in the heart of the people. University, Meerut, The large screen provides an alternative, an escape from the realities of day-to-day life. People cry, Uttar Pradesh, India. laugh, sing, dance and enjoy emotions through cinema. The Cinema of India comprises of films made from corner to corner in India. Film has huge acclaim in the nation. Upwards of 1800 motion pictures Ambar Pandey in various languages are framed in consistently. The quantity of movies made and the quantity of Faculty of Journalism & Mass tickets are selling. Indian film is the biggest film industry on the planet in 2011 over 3.5 billion tickets Communication, Swami were sold over the world. Indian movies have an expansive all through Southern Asia and are realistic Vivekenand Subharti in standard films crosswise over different pieces of Asia, Europe, the Greater Middle East, North University, Meerut, America, Eastern Africa, and somewhere else. Indian film is viewed as the world's biggest film Uttar Pradesh, India. industry with profound respect to the quantity of movies it produce and the quantity of individuals working inside the film government. -

CIN COMPANY NAME First Name Middle Name Last Name Father

COMPANY DATE OF AGM CIN L29130MH1962PLC012340 FAG BEARINGS INDIA LIMITED 25-Apr-13 NAME (DD-MON-YYYY) Sum of Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend 383752.00 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed Dividend 0.00 Sum of matured Deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured Debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 First name Father/Husb Father/Hus Father/Husb Folio Number Investment type Proposed Middle Last and First band and Last of Securities Amount date of Address Country State District PIN Code Name Name Name Middle Name Due(in Rs.) transfer to Name Name IEPF TH CENTURY FINANCE NIL IIT HOUSE OPP VAZIR GLASS FAG Amount for CORPORATION LT WORKS OFF M VASANJI 000000000001 unclaimed and ROAD,ANDHERI(E) MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA 400059 0874 unpaid dividend 11000.00 01-Jun-2014 A C DAVE NA BANK OF INDIA SOCIETY FAG Amount for NEAR SHARDA MANDIR INDIA GUJARAT 380007 00000000000 unclaimed and 200.00 01-Jun-2014 ROAD PALDI 01023 unpaid dividend A SANKAR R DOOR NO.70 FIRST STREET FAG Amount for ARUMUGAM VARNAPURAM INDIA TAMIL NADU 638301 00000000000 unclaimed and 400.00 01-Jun-2014 BHAVANI(P.O.) ERODE 27628 unpaid dividend ABDUL KADAR ALLARAKH NA SHIVAJI ROAD, KOPARGAON. FAG Amount for RANGREJ INDIA MAHARASHTRA 413709 000000000000 unclaimed and 480.00 01-Jun-2014 0479 unpaid dividend ABIDA A DESAI NA 14 KHURSHID PARK SARKHEJ FAG Amount for ROAD AHMEDABAD IN3012761073 unclaimed and INDIA GUJARAT 380055 20.00 01-Jun-2014 -

PM Invites Rajinikanth to Film 'Kabali' Sequel in Malaysia from Sh Nur

PM Invites Rajinikanth To Film 'Kabali' Sequel In Malaysia From Sh Nur Shahrizad Sy Mohamed Sharer CHENNAI, March 31 (Bernama) -- Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak has offered Tamil film star Rajinikanth to film the sequel of 'Kabali' in Malaysia. The Malaysian prime minister said he conveyed this in a meeting with the hugely popular Indian film actor and director here today. Najib said the offer was part of a strategy to market Malaysia's beauty and uniqueness to tourists from India and increase tourist arrivals from that country. "I see the prospect of national tourism being more widely marketed in this country and that is why, I went to meet Rajinikanth and offer him to film the sequel of 'Kabali' in Malaysia. "What I saw in the film feature was the beauty of the country," he said, adding that he received a positive response from the actor over the offer. Najib said Tamil Nadu's new chief minister, Edappati Palaniswami gave an assurance of cooperation to ensure the Kuala Lumpur-Tamil Nadu relations were taken to a higher level. He said the visit also opened up more prospects for investment, with the 23 industry pioneers representing various sectors met today, showing interest to expand to Malaysia. Among the sectors with potential were medicine, education and aerospace, added the Malaysian prime minister. He said Tamil Nadu also offered Malaysian companies an opportunity to invest there, especially in the Free Trade Zone in Chennai. Najib, who is on a six-day visit to India left for New Delhi before heading to Jaipur. -

STUDY on the IMPACT of CREATIVE LIBERTY USED in INDIAN HISTORICAL SHOWS and MOVIES H S Harsha Kumar HOD, Department of Journalis

INTERNATIONALJOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARYEDUCATIONALRESEARCH ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2020); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:1(4), January :2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF CREATIVE LIBERTY USED IN INDIAN HISTORICAL SHOWS AND MOVIES H S Harsha Kumar HOD, Department of Journalism, Government First Grade College Vijayanagar, Bangalore Introduction Historical references in movies, shows are the latest trends in the entertainment industry. In India there are more than 150 movies and 40 T.V shows approximately produced on the historical events and records. Many of these produced by the various makers to retell the tales of glory and valour of India’s great heroes do provide justice to the heroes to some extent. Authentic and accurate depictions for the sake of knowledge or even getting the glimpses of the history is not the outcome of these shows or movies. Various inconsistencies, differences and various inaccuracies regarding the script, scenes and execution, laymen are often misdirected towards concepts. The idea of creative liberty or artistic license used by the writers to make the best of the historical references provided may cause discrepancies or irregularities difficult to accept by the people or some intellectuals. But, to demand accuracy and authenticity from the Indian historical is, for its fans, to miss the point. The genre, after all, is that the descendant of Indian traditions of myth, folklore, ballads and popular history, which have combined to inform us more about an imagined past than an actual one. -

Rajini's Finger, Indexicality, and the Metapragmatics Of

Rajini’s Finger, Indexicality, and the Metapragmatics of Presence Constantine V. Nakassis, University of Chicago ABSTRACT This article explores the ways in which Tamil film stars, so-called mass heroes such as the “Superstar” Rajinikanth, are presenced in theatrical events of their onscreen revela- tion and apperception. Drawing on film analysis, ethnographic accounts of theatrical re- ception, and metadiscourse by filmgoers and industry personnel, I focus on Rajini’s onscreen pointing gestures in highly charged moments of presencing. As I argue, these data provoke reflection on indexicality—defined by Charles Sanders Peirce as a semiotic ground based on “real connection” or “existential relation,” such as copresence, contigu- ity, or causality—for at issue with Rajini’s fingers is precisely the question of his auratic being and presence. Instead of analyzing performative acts of presencing through appeal to the analytic of indexicality, then, what if we interrogate those ethnographic particular- ities of existence and presence that constitute the ground for indexical relations and ef- fects as such? Such an inquiry would refuse to leave indexicality as a self-evident, pregiven analytic, but instead pose it as an open ethnographic question. Opening up the question of existence and presence, as I show, allows us to unearth other semiotic “grounds” of indexicality and representation beyond those that we all too often take for granted. Contact Constantine V. Nakassis at Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago, 1126 E. 59th Street, Chicago, IL 60637 ([email protected]). An earlier version of this article was presented in the panel “Parsing the Body” at the AAA annual meet- ing, Washington, DC, December 4, 2014, organized by Mary Bucholtz and Kira Hall; an expanded draft was discussed at the workshop “Semiotics of the Image” (University of Chicago, October 14–15, 2016) with Chris- topher Ball, Lily Chumley, Keith Murphy, and Justin Richland. -

Film Industry in North India: Reaching New Heights December 2017

Film Industry in North India: Reaching new heights December 2017 Film Industry in North India: Reaching new heights Contents Foreword 05 Executive Summary 06 Overview of the Indian Film Industry 08 Snapshot of the North Indian Film Industry 10 Key Trends in Delivery of North Indian Film Content 16 State of Ancillary and Allied Industries in the North Indian Film Industry 20 Policy and Taxation Environment in North India 27 Concluding Remarks 34 Acknowledgements 38 Contacts 38 03 Film Industry in North India: Reaching new heights 04 Film Industry in North India: Reaching new heights Foreword There has been a revived interest in regional cinema with films doing well both domestically and internationally. This trend is reflected in the rising share of regional films in the Indian box office collections. Having realized the cultural and economic potential of the regional film industries, several Indian state governments are taking initiatives to effect the growth of their native film sectors. The objective of this publication is to provide an overview of the north Indian film industry in India and highlight key initiatives that may be undertaken by various stakeholders to propel growth. Ashesh Jani In order to understand the growth opportunities, the report assesses the current state of the industry with respect to industry structure, language-wise split, formats of delivery, and expected growth. The north Indian film industry has lagged behind its southern counterpart in reach and ability to monetize the various distribution channels. The report analyses underlying factors to overcome these challenges. Supporting industries such as the music industry and the skill development industry, infrastructure facilities such as technical studios and animation and VFX labs, and industry collaborations play a critical role in development of the film industry.