The Role of Congress in Professional Boxing Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unbeaten Heavyweights Step up to the Challenge on NBC Sports Network Inaugural Fight Night Broadcast

PRESS RELEASE January 17, 2012 Unbeaten Heavyweights Step Up to the Challenge on NBC Sports Network Inaugural Fight Night Broadcast In a classic match-up of boxer vs. puncher, two talented, undefeated Philadelphia heavyweights have agreed to move up into the spotlight and put their perfect records on the line this coming Saturday, January 21st at Philadelphia's legendary Asylum Arena on the inaugural broadcast of the NBC Sports Network's "Fight Night" boxing series. Coverage on the NBC Sports Network begins Saturday at 9 p.m. ET. The spectacular cross-town match-up of equally talented rivals will pit Maurice "Freight Train" Byarm and Bryant "Bye Bye" Jennings in the ten-round co-main event. Byarm and Jennings will risk their undefeated records and their neighborhood pride as each takes on the role of a real life "Rocky" and steps into the ring on short notice. The originally scheduled main event, featuring heavyweights Eddie Chambers and Sergei Liakhovich, was scrapped when Chambers revealed on Friday that he had suffered two broken ribs in training. "This series is about giving the fans exciting, action-packed fights where the outcome is in doubt," said promoter Kathy Duva of Main Events. "It is truly a shame that Chambers and Liakhovich cannot fight on Saturday, but athletes get injured. We tried all weekend to find a suitable replacement to face Liakhovich, but truly competitive opposition could not be found on such short notice. Last night we decided that it would be in the best interests of the fans and the series to go in another direction and present a fight that will live up to the standards that we have set for this project. -

Wba March 2004 Ratings Movements

WBA MARCH 2004 RATINGS MOVEMENTS HEAVYWEIGHT PROMOTIONS None DEMOTIONS None REMOVALS 8 Mike Tyson as he is inactive since February 2003 ENTRIES 8 Lance Whitaker at the discretion of the Ratings Committee after considering his record and regional achievements (NABA champion) CRUISERWEIGHT PROMOTIONS Pietro Aurino goes up three positions after Thomas Hansvoll’s demotion and his victory against Sergio Beaz on March 27. Vincenzo Cantatore goes up one position after Thomas Hansvoll’s demotion and his victory against Ismail Abdoul on March 27. Aurino prevailed over Cantatore due to his regional achievements (EBA champion) DEMOTIONS Thomas Hansvoll goes down two positions as he is inactive since October 2003 REMOVALS 6 Alexander Gurov as he is inactive since March 2003; last fight was a TKO loss 15 Daniel Roswell as he has been inactive since his TKO 1 loss to Valery Brudov in December 2003 ENTRIES 8 Guillermo Jones at the discretion of the Ratings Committee after considering his record and caliber 15 Steve Cunningham at the discretion of the Ratings Committee after considering his record LIGHT HEAVYWEIGHT PROMOTIONS Thomas Ulrich goes up one position as reacommodation after Bruno Girard’s demotion Hugo Garay goes up one position as reacommodation after Fabrice Tiozzo’s and David Telesco’s removals Danny Batchelder, Paul Murdoch, and Peter Oboh go up two positions each as reacommodation after Fabrice Tiozzo’s, Montell Griffin’s and David Telesco’s removals 1 DEMOTIONS Bruno Girard goes down four positions as he is inactive since March 2003 REMOVALS -

Wild Bulls, Discarded Foreigners, and Brash Champions: US Empire and the Cultural Constructions of Argentine Boxers Daniel Fridman & David Sheinin

Wild Bulls, Discarded Foreigners, and Brash Champions: US Empire and the Cultural Constructions of Argentine Boxers Daniel Fridman & David Sheinin In the past decade, scholars have devoted growing attention to American cultural influences and impact in the Philippines, Panama, and other societies where the United States exerted violent imperial influences.1 In countries where US imperi- alism was less devastating to local political cultures, the nature of American cultur- al influence and the impact such force had is less clear and less well documented.2 Argentina is one such example. American political and cultural influences in twen- tieth-century Argentina cannot be equated with the cases of Mexico or the Dominican Republic, nor can they be said to have had as profound an impact on national cultures. At the same time, after 1900, US cultural influences were perva- sive in and had a lasting impact on Argentina. There is, to be sure, a danger of trivializing the force of American Empire by confusing Argentines with Filipinos as subject peoples. Argentina is not a “classic” case of US imperialism in Latin America. While the United States supported the 1976 coup d’état in Argentina, for example, there is no evidence of Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and US military backing on a scale equivalent to the 1964 military coup in Brazil or the 1973 overthrow of democracy in Chile. Although American weapons and military strategies were employed by the Argentine armed forces in state terror operations after 1960, there was no Argentine equivalent -

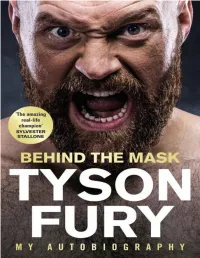

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Rules and Regulations

1 / 21 World Professional Boxing Federation 1 United States Boxing Council RULES AND REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Article 01. General Introduction Article 02. Championship Committee Article 03. Meeting and Vote Article 04. Weight Divisions Article 05. Weight and Weigh-In 5.1 Timing of Initial Weigh-In 5.2 Weight Determines the Championship. 5.3 Champion's Failure to Make Weight. 5.4 Challenger's Failure toMake Weight. 5.5 Failure to Make Weight for Vacant Title or Elimination Bout. 5.6 Both Boxers Failure to Make Weight. 5.7 Weigh-ins For Postponement. Article 6. Defense of Title A. Heavyweight Division 6.1 Mandatory Defense Periods. 6.2 Mandatory Defense Periods For Vacant Title. 6.3 Mandatory Defense Periods For New Champion. B. All Other Weight Divisions 6.4 Mandatory Defense Periods. 2 / 21 6.5 Mandatory Defense Periods For Vacant Title. 2 6.6 Mandatory Defense Periods For New Champion. 6.7 Voluntary Defense. 6.8 Time Limitations. 6.9 Notice of Mandatory Defense. Article 7. Leading Available Contender Article 8. Failure of Champion to Fulfill Contract and Rules Article 9. Unsanctioned Championship or Non-Championship Bout Article 10. Procedure When Title Is Declared Vacant Article 11. Draw Decision Article 12. Rematch Article 13. Disqualification Article 14. Return Bouts Article 15. Purse Bid Procedures 15.1 Call For Purse Bid. 15.2 Notification of Purse Bid. 15.3 Promoter's Obligation. 15.4 Form of Purse Bid. 15.5 Contents of Purse Bid. 15.6 Minimum Purse Bids. 15.7 Winning Bidder. 15.8 Non-Transfer. 15.9 Purse Offer Contracts. -

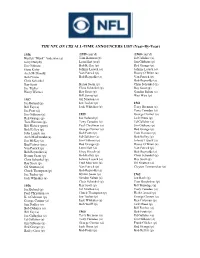

THE NFL on CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year)

THE NFL ON CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year) 1956 (1958 cont’d) (1960 cont’d) Hartley “Hunk” Anderson (a) Tom Harmon (p) Ed Gallaher (a) Jerry Dunphy Leon Hart (rep) Jim Gibbons (p) Jim Gibbons Bob Kelley (p) Red Grange (p) Gene Kirby Johnny Lujack (a) Johnny Lujack (a) Arch McDonald Van Patrick (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Bob Prince Bob Reynolds (a) Van Patrick (p) Chris Schenkel Bob Reynolds (a) Ray Scott Byron Saam (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Joe Tucker Chris Schenkel (p) Ray Scott (p) Harry Wismer Ray Scott (p) Gordon Soltau (a) Bill Symes (p) Wes Wise (p) 1957 Gil Stratton (a) Joe Boland (p) Joe Tucker (p) 1961 Bill Fay (a) Jack Whitaker (p) Terry Brennan (a) Joe Foss (a) Tony Canadeo (a) Jim Gibbons (p) 1959 George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) Joe Boland (p) Jack Drees (p) Tom Harmon (p) Tony Canadeo (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bill Hickey (post) Paul Christman (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Bob Kelley (p) George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) John Lujack (a) Bob Fouts (p) Tom Harmon (p) Arch MacDonald (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bob Kelley (p) Jim McKay (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Bud Palmer (pre) Red Grange (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Van Patrick (p) Leon Hart (a) Van Patrick (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Elroy Hirsch (a) Bob Reynolds (a) Byrum Saam (p) Bob Kelley (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Ray Scott (p) Ray Scott (p) Fred Morrison (a) Gil Stratton (a) Gil Stratton (a) Van Patrick (p) Clayton Tonnemaker (p) Chuck Thompson (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Joe Tucker (p) Byrum Saam (p) 1962 Jack Whitaker (a) Gordon Saltau (a) Joe Bach (p) Chris Schenkel -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04Rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA Won Title: 04-02-05 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13 -03 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: 04-30 -05 _________________________________ Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 04-30 -05 World C hampion: VACANT Last Defense: 02-26- 05 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: JEAN MARC MORMECK- IBF: O’NEIL BELL WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBO : JOHNNY NELSON WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI 1. NICOLAY VALUEV (OC) RUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. JORGE CASTRO (LAC) ARG 2. NOT RATED 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. GUILLERMO JONES (0C) PAN 3. MANNY SIACA (LAC-INTERIM) P.R. ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. RAY AUSTIN (LAC) USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( 5. CALVIN BROCK USA 5. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA l 6. -

State Athletic Commission 10/25/13 523

523 CMR: STATE ATHLETIC COMMISSION Table of Contents Page (523 CMR 1.00 THROUGH 4.00: RESERVED) 7 523 CMR 5.00: GENERAL PROVISIONS 31 Section 5.01: Definitions 31 Section 5.02: Application 32 Section 5.03: Variances 32 523 CMR 6.00: LICENSING AND REGISTRATION 33 Section 6.01: General Licensing Requirements: Application; Conditions and Agreements; False Statements; Proof of Identity; Appearance Before Commission; Fee for Issuance or Renewal; Period of Validity 33 Section 6.02: Physical and Medical Examinations and Tests 34 Section 6.03: Application and Renewal of a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.04: Initial Application for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant New to Massachusetts 35 Section 6.05: Application by an Amateur for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.06: Application for License as a Promoter 36 Section 6.07: Application for License as a Second 36 Section 6.08: Application for License as a Manager or Trainer 36 Section 6.09: Manager or Trainer May Act as Second Without Second’s License 36 Section 6.10: Application for License as a Referee, Judge, Timekeeper, and Ringside Physician 36 Section 6.11: Application for License as a Matchmaker 36 Section 6.12: Applicants, Licensees and Officials Must Submit Material to Commission as Directed 36 Section 6.13: Grounds for Denial of Application for License 37 Section 6.14: Application for New License or Petition for Reinstatement of License after Denial, Revocation or Suspension 37 Section 6.15: Effect of Expiration of License on -

If,Epte% Meitieeta

if,epte% meitieeta VOLUME XX WASHINGTON, D.C., JULY-AUGUST, 1966 NUMBER 106 PACIFIC Cleveland's brief and inspirational discuss Bible truths with Mr. Moore. stay, several church appointments An appointment was arranged and General Conference Visitors were arranged for him. In the middle Elder Fountain was able to give of the week, on Wednesday night, he Archie Moore his first Bible study with in the Pacific Union spoke to a large congregation at the regard to the Adventist faith. Mr. Philadelphian church in San Fran- Moore, who was then residing in San DURING the month of April and the cisco. On Sabbath morning, May 7, Diego, California, was later contacted first part of May the Regional con- he again spoke to a packed audience in the evangelistic Go Tell visitation gregations throughout California have at the Normandy Avenue church in program of Evangelist Eric Ward, been thrilled with the visits from some Los Angeles, and on Sabbath after- who was building up a program of a of our General Conference brethren. noon he was the guest speaker at a large evangelistic campaign in the F. L. Peterson and C. E. Moseley large union meeting in the new city of San Diego. During the course have both traveled up and down our Tamarind church in Compton, South of this Go Tell campaign Mr. Moore California Coast and have had speak- Los Angeles, where many were thrilled was contacted time and again and ing engagements in many churches. with his dynamic message. had the opportunity to study the Fam- Congregation after congregation have We are more than grateful for the ily Bible Course that was presented expressed their appreciation for the inspirational visit of these godly men by the house-to-house visitation in the messages that have been given by in our midst during these weeks pre- Go Tell campaign of this time. -

Nominees for the 29 Annual Sports Emmy® Awards

NOMINEES FOR THE 29 TH ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCE AT IMG WORLD CONGRESS OF SPORTS Winners to be Honored During the April 28 th Ceremony At Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frank Chirkinian To Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – March 13th, 2008 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards at the IMG World Congress of Sports at the St. Regis Hotel in Monarch Bay/Dana Point, California. Peter Price, CEO/President of NATAS was joined by Ross Greenberg, President of HBO Sports, Ed Goren President of Fox Sports and David Levy President of Turner Sports in making the announcement. At the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards, winners in 30 categories including outstanding live sports special, sports documentary, studio show, play-by-play personality and studio analyst will be honored. The Awards will be given out at the prestigious Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center located in the Time Warner Center on April 28 th , 2008 in New York City. In addition, Frank Chirkinian, referred to by many as the “Father of Televised Golf,” and winner of four Emmy ® Awards, will receive this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award that evening. Chirkinian, who spent his entire career at CBS, was given the task of figuring out how to televise the game of golf back in 1958 when the network decided golf was worth a look. Chirkinian went on to produce 38 consecutive Masters Tournament telecasts, making golf a mainstay in sports broadcasting and creating the standard against which golf telecasts are still measured. -

360° Real Estate Expertise

360° real estate expertise An excellent team no matter the topic Financial services Construction Financing Equity / mezzanine phase Research & financing valuation Land Transactions development Municipality property Investment development (purchase and sale) & asset management Utilisation phase Facility & property management Gero Bergmann Bernd Mayer National and international presence. Member of Real Estate So you get expert advice on-site the Board of Division • Strong in Germany and Europe Management, Manager, BayernLB BayernLB • Present in all the established global markets – from the US to Australia • Regional market specialisation • Help in accessing markets “We offer our customers a Seamless range of services. seamless range of services So we can respond to your specific needs along the value-added chain.” • Top-notch products and services • Modular structure for the entire service range • Products and services that are made for one another • Individualised all-in-one packages 360° real estate expertise. Strong Group network. So your projects are covered on all sides So we can work smoothly with your team • Every Group member a renowned market player • No unnecessary interfacing between project partners • Bundled expertise • Quick response times even for complex queries • All specialists working together • All project partners working in concert ° real estate expertise Contents BayernLB Successful financier for commercial and residential property 4 Financial services DKB At home in a sector, connected throughout Germany 10 Real -

Read the Full Sdm Magazine Article Here

AAA NCNU acquires SAFE Security Wholesale monitoring center innovations Beefing up VMS capabilities December 2018 PERIODICALS AS SEEN IN All in the FAMILY Bates Security/Sonitrol of Lexington recently chose to branch out through a combination acquisition and startup; as well as pilot a groundbreaking standardization program — all while never compromising the family atmosphere that started it all. By Karyn Hodgson, SDM Managing Editor exington, Ky., is known for a few things: horses, bluegrass, bourbon, a historic downtown area and — when it comes to security systems — Bates LSecurity/Sonitrol. Started in 1969 as Sonitrol of Lexington, the Bates family moved from Dallas in the early 1980s after purchasing the franchise from Ann Miller. Sonny Bates, his wife Pat, and their two young sons made the move after Sonny, a retired Dallas police officer, decided to strike out on his own with a Sonitrol franchise. “I was a police Bryan Bates (left) and Jeremy Bates (right) took over the day-to-day operations of the company from their parents, and have expanded to two different cities, in addition to continuing the SDM company’s dominance in its Lexington, Ky. market. The entire block of buildings behind them in the above picture are or will be secured by Bates Security/Sonitrol of Lexington. PHOTO BY MARK MAHAN FOR December 2018 officer for nine years and didn’t know anything about is audio detection and verification,” says Crystal alarm systems other than answering them,” Sonny Newton, marketing manager. “When the signal comes Bates recalls. “But we were catching burglars on the in the operator knows exactly what is going on.