Aberystwyth University Reconstructed Centennial Variability of Late

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cors Fochno Walk MEWN ARGYFWNG O Warchodfa Natur Part of the Dyfi National Ffoniwch 999

Gwarchodfa Natur Genedlaethol Dyfi National Nature Reserve Cors Fochno Croeso i Cors Fochno - rhan Welcome to Cors Fochno - Llwybrau Cerdded Cors Fochno Walk MEWN ARGYFWNG o Warchodfa Natur part of the Dyfi National Ffoniwch 999. PERYGLON Genedlaethol Dyfi (GNG) Nature Reserve Arhoswch ar y byrddau cerdded pren – Mae’r warchodfa fawr hon yn cwmpasu dros This large reserve covers an area of over 2,000 ha, peidiwch â suddo na mynd yn sownd! 2,000 hectar, ac mae’n cynnwys tair prif ardal a and is made up of three main areas and many FEL Y GALL PAWB EU MWYNHAU nifer o wahanol gynefinoedd ar gyfer bywyd dierent habitats for wildlife and plants. • Dim cŵn os gwelwch yn dda, i osgoi aflonyddu gwyllt a phlanhigion. ar fywyd gwyllt sensitif Cors Fochno (Borth Bog): one of the largest and finest • Dim gwersylla dros nos na defnyddio cerbydau Cors Fochno: un o’r enghreitiau mwyaf a gorau sydd ar remaining examples of a raised peat bog in Britain. gwersylla yn y Warchodfa ôl o gyforgors fawn ym Mhrydain. Ynyslas Dunes: the largest dunes in Ceredigion and Cofnodi’r dystiolaeth Taking down the evidence • Dim tanau Twyni Ynyslas: y twyni mwyaf yng Ngheredigion ac er ei although the smallest of the three areas of the Dyfi NNR, by Am dros 6,000 o flynyddoedd mae mawn wedi bod yn cronni yma’n Peat has been accumulating here gradually and continuously for over bod yr ardal leiaf yng Ngwarchodfa Natur Genedlaethol Dyfi, far the most visited. raddol ac mae nawr wedi cyrraedd dyfnder o dros 6m! Mae 6,000 years and now reaches a depth of over 6m! Remains of each dyma’r ardal sy’n derbyn y nifer mwyaf o ymwelwyr. -

Did Prehistoric and Roman Mining and Metallurgy Have a Significant

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 11 (2017) 613–625 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Did prehistoric and Roman mining and metallurgy have a significant impact on vegetation? TMighalla,⁎,S.Timberlakeb,c, Antonio Martínez-Cortizas d, Noemí Silva-Sánchez d,I.D.L.Fostere,f a Department of Geography & Environment, School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Elphinstone Road, Aberdeen AB24 3UF, UK b Cambridge Archaeological Unit, Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, 34A Storeys Way, Cambridge, CB3 ODT, UK c Early Mines Research Group, Ashtree Cottage, 19, The High Street, Fen Ditton, Cambridgeshire CB5 8ST, UK d Departamento de Edafología y Química Agrícola, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Santiago, Campus Sur, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain e School of Science and Technology, University of Northampton, Newton Building, Northampton NN2 6JD, UK f Department of Geography, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 6140, Eastern Cape, South Africa article info abstract Article history: To develop our understanding of the relationship between vegetation change and past mining and metallurgy Received 30 September 2016 new approaches and further studies are required to ascertain the significance of the environmental impacts of Received in revised form 8 December 2016 the metallurgical industry. Using new pollen and geochemical data from Cors Fochno (Borth Bog), Wales, we ex- Accepted 11 December 2016 amine whether prehistoric and Roman mining and metallurgy had a significant impact on the development of Available online xxxx vegetation and compare the findings with previous studies across Europe on contamination and vegetation change to develop a conceptual model. -

Gwarchodfa Natur Genedlaethol National Nature Reserve

ArweiniadFo i’r Warchodfa Guide to Reserve Gwarchodfa Natur Genedlaethol Dyfi National Nature Reserve // Darganfyddwch dwyni, morfa heli a chors Dyfi Discover Dyfi’s dunes, saltmarsh and peat bog www.cyfoethnaturiol.cymru www.naturalresources.wales Darganfod Discovering Dyfi Gwarchodfa Natur National Nature Genedlaethol Dyfi Reserve Y rhan fwyaf cyfarwydd a hawsaf ei chyrraedd yng The dunes at Ynyslas are the most familiar – and Ngwarchodfa Natur Genedlaethol Dyfi yw’r twyni yn accessible – part of Dyfi National Nature Reserve Ynyslas. Ond nid dyma’r cyfan sydd ganddi i’w chynnig. (NNR). But they aren’t the whole story. There’s an Mae amrywiaeth aruthrol o wahanol gynefinoedd yma, outstanding range of different habitats here, including sy’n cynnwys traethau llanwol ysgubol a morfeydd heli the sweeping tidal sands and saltmarshes of the Dyfi Aber Afon Dyfi a chyforgors Cors Fochno; y cyfan yn Estuary and the raised peat bog of Cors Fochno, all of rhoi rhwydd hynt i fywyd gwyllt cyfoethog a rhyfeddol. which play host to a rich and fascinating wildlife. Mae’r warchodfa enfawr hon yn ymestyn dros 2,000 hectar, This huge reserve covers an area of over 2,000 hectares, ac yn cynnwys tair ardal wahanol iawn: and is made up of three very different areas: Twyni Ynyslas: dyma’r twyni mwyaf yng Ngheredigion sy’n Ynyslas Dunes: the largest dunes in Ceredigion and by far denu’r nifer uchaf o ymwelwyr. Mae’r llethrau a’r pantiau the most visited. The sandy slopes and hollows provide tywodlyd yn cynnig cartref i anifeiliaid bychain di-ri gan homes for a myriad of small animals including rare spiders, gynnwys corynnod prin, gwenyn turio a glöynnod byw mining bees and spectacular butterflies like dark green syfrdanol fel brithion gwyrdd. -

Ynyslas Nature Reserve: Aberdyfi Estuary

Comisiwn Brenhinol Henebion Cymru _____________________________________________________________________________________ Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales YNYSLAS NATURE RESERVE: ABERDYFI ESTUARY Non Intrusive Survey County: Ceredigion Community: Borth and Llangynfelyn Site Name: Ynyslas Nature Reserve NGR: SN61209350 (centre of extensive site/area) Date of Survey: June 2008 – October 2010 Survey Level: 1 a and 1b Surveyed by: Deanna Groom and Medwyn Parry, RCAHMW Robin Ellis, Aberystwyth Civic Society Report Author: Deanna Groom and Medwyn Parry Illustrations: Deanna Groom, Medwyn Parry, Robin Ellis and Nick Cook © Crown Copyright: RCAHMW 2012 CBHC/RCAHMW Plas Crug Aberystwyth Ceredigion SY23 1NJ Tel: 01970 621200 World Wide Web: http//www.rcahmw.gov.uk 1 YNYSLAS NATURE RESERVE: ABERDYFI ESTUARY Non Intrusive Survey Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2 STUDY AREA .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Geology and Geomorhology ......................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Aims and Objectives ..................................................................................................................... -

Appendix I: European Site Characterisations

Appendix I HRA Anglesey & Gwynedd Joint LDP Appendix I: European Site Characterisations Special Areas of Conservation 1. Abermenai to Aberffraw Dunes SAC 2. Afon Eden - Cors Goch Trawsfynydd SAC 3. Afon Gwyrfrai a Lyn Cwellyn SAC 4. Anglesey Coast: Saltmarsh SAC 5. Anglesey Fens SAC 6. Berwyn and South Clwyd Mountains SAC 7. Cadair Idris SAC 8. Cemlyn Bay SAC 9. Coedydd Aber SAC 10. Cors Fochno SAC 11. Corsydd Eifionydd SAC 12. Glan-traeth SAC 13. Glynllifon SAC 14. Great Orme’s Head SAC 15. Holy Island Coast SAC 16. Llyn Fens SAC 17. Llyen Peninsula and the Sarnau SAC 18. Llyn Dinam SAC 19. Meirionnydd Oakwoods and Bat Sites SAC 20. Menai Strait and Conwy Bay SAC 21. Migneint - Arenig - Dduallt SAC 22. Morfa Harlech a Morfa Dyffryn SAC 23. Preseli SAC 24. Rhinog SAC 25. River Dee and Bala Lake SAC 26. Sea Cliffs of Lleyn SAC 221/A&G JLDP February 2015 1 / 145 ENFUSION Appendix I HRA Anglesey & Gwynedd Joint LDP 27. Snowdonia SAC Special Protection Areas 1. Aberdardon Coast and Bardsey Island SPA 2. Berwyn SPA 3. Craig yr Aderyn SPA 4. Dyfi Estuary SPA 5. Elenydd - Mallaen SPA 6. Holy Island Coast SPA 7. Lavan Sands, Conway Bay SPA 8. Liverpool Bay SPA 9. Migneint - Arenig - Dduallt SPA 10. Mynydd Cilan, Trwyn y Wylfa ac Ynysoedd Sant Tudwal SPA 11. Puffin Island SPA 12. Ynys Feurig, Cemlyn Bay and the Skerries SPA Ramsar 1. Anglesey and Llyn Fens Ramsar 2. Cors Fochno and Dyfi Ramsar 3. Llyn Idwal Ramsar 4. Llyn Tegid Ramsar 221/A&G JLDP February 2015 2 / 145 ENFUSION Appendix I HRA Anglesey & Gwynedd Joint LDP Special Areas of Conservation Abermenai to Aberffraw Dunes SAC Overview The Abermenai to Aberffraw Dunes Special Area of Conservation (SAC) is at the southern end of the Menai Strait in Ynys MÔn and Gwynedd, Wales. -

Ceredigion Bird Report 2019 Final

Ceredigion Bird Report 2019 0 CEREDIGION BIRD REPORT 2019 Contents Editorial and submission of records, Arfon Williams page 2 Systematic list, Russell Jones 5 Earliest and last dates of migrants, Arfon Williams 51 Ceredigion rarity record shots for 2019 52 The Ceredigion bird ringing report, Wendy James 54 The Definitive Ceredigion Bird List, Russell Jones 62 Spectacle off Ynyslas, Edward O’Connor 71 Swifts, Bob Relph 72 Bow Street Swifts, Tony Clark 73 Gazetteer of Ceredigion places 74 County Recorder and Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) Organiser: Russell Jones, Bron-y-gan, Talybont, Ceredigion, SY24 5ER Email: [email protected] British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) Representative: Naomi Davies Email: [email protected] Tel: 07857 102286 Front cover: Barn Owl by Tommy Evans 1 Editorial A total of 217 species were seen in Ceredigion in 2019, a slightly higher than average annual figure. There were no new county firsts, however Ceredigion’s first King Eider, initially seen in 2017, returned for a third year. Other rare and scare birds included the county’s fourth Bean Goose, a male Ring-necked Duck (6th record), a female Smew, two calling Quail, Ceredigion’s 7th Cattle Egret and Purple Heron, a Glossy Ibis (4th record), three Spoonbills, a Honey Buzzard, Spotted Crake, Common Crane (6th record) and Temminck’s Stint (9th record), the county’s third Alpine Swift (and first since 1993), a Great Grey Shrike, two Yellow-browed Warblers, two blue-headed Yellow Wagtails, a Richard’s Pipit and a single Lapland Bunting. Whilst some species are appearing more frequently e.g. -

Dyfi Opportunities

Opportunities for sustainably managing the Dyfi’s natural resources…to benefit people, the economy and the environment Vol.1 - September 2016 1 Contents Purpose and status of this document Vol 1. 1 Introduction and background 1.1 What is the issue 1.2 What area does the Opportunities Document cover 1.2.1 The legislation 1.3 Why has the Opportunities Document been produced 1.4 How has the Opportunities Document been produced 2 Benefits 2.1 How our natural resources support the economy 2.1.1 Agriculture 2.1.2 Forestry 2.1.3 Outdoor activities 2.1.4 Renewable energy 2.1.5 Mineral resources 2.2 How our natural resources protect us 2.3 How our natural resources support recreation, culture, wildlife and health 3 Challenges & Issues 2 Vol 1 Maps Map No Topic 1 Location of the Dyfi Catchment 2 Productivity of Agricultural land 3 Areas of ‘productive’ woodland 4 Number and variety of businesses related to fishing around the estuary 5 Geology of the Dyfi 6 Areas of land that help prevent flooding 7 The extensive range of habitats in the estuary 8 The contribution of land to preventing sedimentation and erosion 9 The carbon stock contained within soils and vegetation combined 10 Extensive Rights of Way network 10a Scheduled Ancient Monument sites 10b Landscape areas 11 SSSI and Special Area of Conservation sites (SAC) in the Dyfi 12 Communities most at risk of flooding 13 Areas that are storing and emitting carbon 14 Areas generating phosphorous 15 Condition of rivers in the Dyfi 3 Vol 1 Appendices Appendix 1 Existing Plans and strategies related to the natural resources of the area Appendix 2 Important ‘ecosystem services’ in Dyfi Appendix 3 Land Use Capability (LUCI) model Vol 2. -

The Buildings Title Page

THE BUILDINGS OF MORFA BORTH - the Marsh Harbour Ceredigion That part of Borth Village on a pebble bank with the sea on one side and the Cors Fochno marsh some reclaimed and the railway on the other. In the distance is the River Dyfi. Photograph Michael Lewis Photographs and History by BERYL LEWIS This work is for research and educational purposes only. AWELON Morfa Borth The first house in the old Township of Cyfoeth-y-brenin and at the north end of the village with the beach over the road. Formerly called Moreland (Moorland) House. The name Awelon in Welsh means ‘cheerful air’. Home of Theophilus and Frances Rees who took in holiday visitors and lodgers, as did carpenter and builder William Williams and his family. Built after 1859 but by 1871. Awelon in 2015. Awelon is an end of terrace house and two storeys high under a gable roof at right angles to the road and within the roof is an attic. The house is double fronted, and its walls are stone, probably rubble stone, and are rendered. The chimneys are narrow and of a dark brick. The four windows and front door seem to be symmetrical which is unusual for Borth. The windows are modern. There is a porch on the front with a sloping lean to roof with a door at the side, and a window with one large light facing the road. This has a quarry tiled floor. The front garden is enclosed by a low wall, and part is planted. Part of the north wall butts against Morlan Bwthyn but is not joined to it. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A study of dissolved organic matter in peatlands: molecular characterisation of a dynamic carbon reservoir Luke McDonald Ridley A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 University of Edinburgh Declaration Ruth Flerus carried out the ESI-FT-ICR-MS analysis and data acquisition (discussed in Chapter 6). CuO oxidation GC-MS analysis and quantification of phenolic compounds in the solid phase was carried out Jason Dallas-Ross and Dafydd Elias, who also assisted in the field in June 2010. All subsequent data analysis and interpretation was carried out by the candidate. All other sample analysis and data collection was carried out by the candidate. The candidate declares that: (a) that the thesis has been composed by the candidate, and (b) either that the work is the candidate's own, or, if the candidate has been a member of a research group, that the candidate has made a substantial contribution to the work, such contribution being clearly indicated, and (c) that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. -

Welsh Water Habitats Regulations Assessment of Draft Water Resources Management Plan 2013

Welsh Water Habitats Regulations Assessment of Draft Water Resources Management Plan 2013 Draft Assessment of Preferred Options AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited March 2013 Third-Party Disclaimer Any disclosure of this report to a third party is subject to this disclaimer. The report was prepared by AMEC at the instruction of, and for use by, our client named on the front of the report. It does not in any way constitute advice to any third party who is able to access it by any means. AMEC excludes to the fullest extent lawfully permitted all liability whatsoever for any loss or damage howsoever arising from reliance on the contents of this report. We do not however exclude our liability (if any) for personal injury or death resulting from our negligence, for fraud or any other matter in relation to which we cannot legally exclude liability. Document Revisions No. Details Date 1 Draft for client review 22.02.13 2 Draft for client review 21.03.13 3 Consultation version 26.03.13 © AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited March 2013 Doc Reg No. 32493RR046i3 iv © AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited March 2013 Doc Reg No. 32493RR046i3 v Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Water resource planning 1 1.2 Habitats Regulations Assessment 1 1.3 This Report 2 2. HRA of Water Resource Management Plans 3 2.1 Guidance 3 2.2 Overview 3 2.3 Key issues for HRA of the WRMP 4 2.3.1 Understanding the likely outcomes of the WRMP 4 2.3.2 Sustainability reductions and the Review of Consents 6 2.3.3 Uncertainty and determining significant or adverse effects 8 2.3.4 Mitigating uncertainty and ‘down the line’ assessment 10 3. -

Dyfi-Nature.Pdf

...., A!> Llangollen• Porthmadog • •Bala Arweiniad i'r Warchodfa ·Pwllheli Cyfoeth Naturiol Guide to Reserve Cymru Natural Resources Wales Y Trallwng Welshpool A4S8 • l Aberystwyth. • ! Aberaero". • SUI i gyrraedd yma flow to get here ~1ae Dyfl: Ynyslas ddau giiometr i Oytl: Ynyslas is tl'lO I.il ometm. nOl1l1 of 9yfeiriad y gogiedd 0 Borth ar y B4353. Borth 011 the 84353. Cyfeirnod Grid yr Arolwg Ordnans OS grid rc iorol1ce S·'. 640 SS SN 640955. Ttle car pur~ (s~asand! narki 9 c. n:J rge) Ma e'r maes parcio (ffi barcio dymhorol) is on ~ ,da\ ~dndS ",',I r,lcl\ Jr ~ co ve r ~d by ar draeth Ilanw sy'n cael ei orchuddio sea'Nater on t" gil ~pr fHJ tlips. gan ddwr y mor adeg lIanw mawr. The visitor centro I OJ.,iOn sellsollilily. Ma e'r ganolfan i ymwelwy r ar agor yn dymhorol. Cludianl cyhoeddus Public transport www.traveline.cymru www.travellne.cymru Os hoffech chi'r cyhoeddiad hwn mewn gwahanol ddiwyg, rhowch wybod inni, OS gwelwch yn dda: ymholiadau@cyfoethnatu rio lcymru.gov.uk '03000653000 If you would like this publication in a different format, please let us know: enquiries'o.:naturalresourceswales.gov.uk 0300 065 3000 ~t(4'f!:i:t a~ ILywodraethNoddl' gao Cymru www.cyfoethnaturiol.cymru '~'>---:1hl Spo",o<ed by pi/, ~ Wel sh Government BimHer ~ I Bj ~e r . www.nat uralresources.wales ...... , ,.:.... .. --. I)is(:o feril19 Dlffi Ilatiollal Ilatlll-e I~esel · ve The dunes at Ynyslas are the most familiar - and accessible - part of Dyfi National Nature Reserve (NNR). -

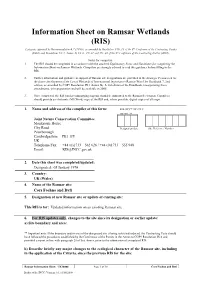

Cors Fochno and Dyfi

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Designation date Site Reference Number Peterborough Cambridgeshire PE1 1JY UK Telephone/Fax: +44 (0)1733 – 562 626 / +44 (0)1733 – 555 948 Email: [email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: Designated: 05 January 1976 3. Country: UK (Wales) 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Cors Fochno and Dyfi 5.