Arxiv:2008.02789V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 6 Aug 2020 Common Planet Size; and Compact Multiple Planet Sys- Tems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Atmospheric Remote-Sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-Survey

ariel The Atmospheric Remote-Sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey Towards an H-R Diagram for Planets A Candidate for the ESA M4 Mission TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 1 2 Science Case ................................................................................................................ 3 2.1 The ARIEL Mission as Part of Cosmic Vision .................................................................... 3 2.1.1 Background: highlights & limits of current knowledge of planets ....................................... 3 2.1.2 The way forward: the chemical composition of a large sample of planets .............................. 4 2.1.3 Current observations of exo-atmospheres: strengths & pitfalls .......................................... 4 2.1.4 The way forward: ARIEL ....................................................................................... 5 2.2 Key Science Questions Addressed by Ariel ....................................................................... 6 2.3 Key Q&A about Ariel ................................................................................................. 6 2.4 Assumptions Needed to Achieve the Science Objectives ..................................................... 10 2.4.1 How do we observe exo-atmospheres? ..................................................................... 10 2.4.2 Targets available for ARIEL .................................................................................. -

Part 1: the 1.7 and 3.9 Earth Radii Rule

Hi this is Steve Nerlich from Cheap Astronomy www.cheapastro.com and this is What are exoplanets made of? Part 1: The 1.7 and 3.9 earth Radii rule. As of August 2016, the current count of confirmed exoplanets is up around 3,400 in 2,617 systems – with 590 of those systems confirmed to be multiplanet systems. And the latest thinking is that if you want to understand what exoplanets are made of you need to appreciate the physical limits of planet-hood, which are defined by the boundaries of 1.7 and 3.9 Earth radii . Consider that the make-up of an exoplanet is largely determined by the elemental make up of its protoplanetary disk. While most material in the Universe is hydrogen and helium – these are both tenuous gases. In order to generate enough gravity to hang on to them, you need a lot of mass to start with. So, if you’re Earth, or anything up to 1.7 times the radius of Earth – you’ve got no hope of hanging onto more than a few traces of elemental hydrogen and helium. Indeed, any exoplanet that’s less than 1.7 Earth radii has to be primarily composed of non-volatiles – that is, things that don’t evaporate or blow away easily – to have any chance of gravitationally holding together. A non-volatile exoplanet might be made of rock – which for our Solar System is a primarily silicon/oxygen based mineral matrix, but as we’ll hear, small sub-1.7 Earth radii exoplanets could be made of a whole range of other non-volatile materials. -

Abstract Ems

abstracts.md A table containing the talk and poster abstracts is posted below, in alphabetical order of last name. The posters themselves can be viewed on ZENODO (click for link), as well as during the gather.town live viewing sessions. Poster identifiers are in a topic.idnumber schema. Categories are as follows: 1. Atmospheres and Interiors . Detection: Transits, RVs, Microlensing, Astrometry, Imaging . Planet Formation (+ Disk) + Evolution . Know Your Star . Population Statistics & Occurrence . Dynamics 3. Instrumentation / Future 4. Habitability & Astrobiology 5. Machine Learning / Techniques / Methods Name (Affiliation). Title. Abstract Where. We present the optical transmission spectrum of the highly inflated Saturn-mass exoplanet WASP- 21b, using three transits obtained with the ACAM instrument on the William Herschel Telescope through the LRG-BEASTS survey (Low Resolution Ground-Based Exoplanet Atmosphere Survey Lili Alderson (University of using Transmission Spectroscopy). Our transmission spectrum covers a wavelength range of 4635- Bristol). LRG-BEASTS: 9000Å, achieving an average transit depth precision of 197ppm compared to one atmospheric scale Ground-bAsed Detection height at 246ppm. Whilst we detect sodium absorption in a bin width of 30Å, at >4 sigma of Sodium And A Steep confidence, we see no evidence of absorption from potassium. Atmospheric retrieval analysis of the OpticAl Slope in the scattering slope indicates that it is too steep for Rayleigh scattering from H2, but is very similar to Atmosphere of the Highly that of HD189733b. The features observed in our transmission spectrum cannot be caused by stellar InflAted Hot-SAturn activity alone, with photometric monitoring and Ca H&K analysis of WASP-21 showing it to be an WASP-21b. -

Kepler 78B Exoplanet Is Earth-Like in Mass and Size 30/10/2013 18:20

Kepler 78b exoplanet is Earth-like in mass and size 30/10/2013 18:20 Kepler 78b exoplanet is Earth-like in mass and size October 30th, 2013 in Space & Earth / Astronomy Enlarge Kepler-78b is a planet that shouldn't exist. This scorching lava world, shown here in an artist's conception, circles its star every eight and a half hours at a distance of less than one million miles. According to current theories of planet formation, it couldn't have formed so close to its star, nor could it have moved there. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA) Kepler-78b is a planet that shouldn't exist. This scorching lava world, shown here in an artist's conception, circles its star every eight and a half hours at a distance of less than one million miles. According to current theories of planet formation, it couldn't have formed so close to its star, nor could it have moved there. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA) In August, MIT researchers identified an exoplanet with an extremely brief orbital period: The team found that Kepler 78b, a small, intensely hot planet 700 light-years from Earth, circles its star in just 8.5 hours—lightning-quick, compared with our own planet's leisurely 365-day orbit. From starlight data gathered by the Kepler Space Telescope, the scientists also determined that the exoplanet is about 1.2 times Earth's size—making Kepler 78b one of the smallest exoplanets ever measured. Now this same team has found that Kepler 78b shares another characteristic with Earth: its mass. -

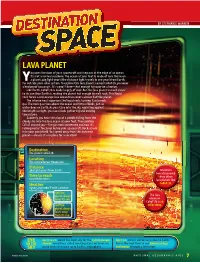

LAVA PLANET Ou Open the Door of Your Spacecraft and Step out at the Edge of an Ocean

BY STEPHANIE WARREN LAVA PLANET ou open the door of your spacecraft and step out at the edge of an ocean. It’s not a normal seashore. The ocean at your feet is made of lava. You’re on Ya planet 489 light-years (the distance light travels in one year) from Earth, far outside your solar system. To explore this lava planet, named CoRoT-7b, you wear a heatproof spacesuit. It’s 3,990°F here—hot enough to vaporize a human. Like Earth, CoRoT-7b is made largely of rock. But the lava planet is much closer to its sun than Earth is, making the planet hot enough to melt rock. This liquid rock forms a red-orange lava ocean that covers almost half the planet. The intense heat vaporizes the liquid rock, turning it into rock gas. The rock gas rises above the ocean and forms clouds, just as water does on Earth. As you stare into the sky, squinting against the bright sunlight, you see clouds gathering and moving toward you. Suddenly you hear the plop of a pebble falling from the cloudy sky into the lava ocean at your feet. Then pebbles fall all around you—the gas rock condensed and now it’s raining rocks! You jump inside your spacecraft. Rocks crash into your windshield. You speed away from this extreme planet—clearly it’s no place for a vacation! Destination The planet CoRoT-7b Location The constellation Monoceros Distance 489 light-years from Earth Scientists have discovered Time to reach three other 13.3 million years lava planets like Weather CoRoT-7b. -

Thursday 11/05/20 This Material Is Distributed by Ghebi LLC on Behalf

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 11/11/2020 3:40:04 PM Thursday 11/05/20 This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. Scientists Determine Lava Planet May Have Supersonic Winds, Atmosphere of Vaporized Rock A group of astronomers recently provided new insight into the atmosphere and weather cycle of a distant, Earth-sized lava planet that may have an atmosphere riddled with vaporized rock that rains down on the fiery world. Published Tuesday in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, scientists from McGill University, York University and the Indian Institute of Science Education indicated they used a variety of computer simulations to determine the living conditions on K2-141b. The distant lava planet, which was originally discovered in 2017, is largely believed to be made up entirely of rock, and as it completes several cycles around its host star in one Earth day, officials found that the temperatures reached on the planet are extreme enough to vaporize rock. Analysis of the simulations determined that K2-141b’s proximity to its host star keeps roughly two-thirds of the exoplanet permanently facing daylight and reaching temperatures of some 3,000 degrees Celsius. Stuck in perpetual darkness, officials estimated the opposing side of the planet sees temperatures of negative 200 degrees Celsius. “Remarkably, the rock vapor atmosphere created by the extreme heat undergoes precipitation,” a release issued by McGill University explains. -

THE PLANETARY REPORT MARCH EQUINOX 2019 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 Planetary.Org

THE PLANETARY REPORT MARCH EQUINOX 2019 VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 planetary.org INSIDE THE ICE GIANTS AFTER VOYAGER, BOTH URANUS AND NEPTUNE HAVE CHANGED THEIR FACES THE SKIES OF MINI-NEPTUNES C CHANGE COMES TO WASHINGTON C PORTRAIT OF MU69 SNAPSHOTS FROM SPACE EMILY STEWART LAKDAWALLA is editor of The Planetary Report. IT’S ONE AMONG millions. Nothing special drew New Horizons to 2014 MU69 (nicknamed “Ultima Thule”), except that it was in the right place at the right time for the fast-flying spacecraft to zip past it. And yet, merely by visiting it, we made 2014 MU69 special, turning it from a dot in the sky so faint that it’s only visible to Hubble into the double-lobed world in this photo. New Horizons will spend another year returning all its data from the encounter, and scientists will spend years—perhaps decades—debating how this odd little binary thing formed and evolved. In the meantime, data artists like Thomas Appéré will help us imagine what 2014 MU69 would look like if we could only travel the NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Thomas Appéré NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Thomas more than 6 billion kilometers (4 billion miles) that separates Earth from it. —Emily Stewart Lakdawalla SEE MORE AMATEUR-PROCESSED SPACE IMAGES PLANETARY.ORG/AMATEUR SEE MORE EVERY DAY! PLANETARY.ORG/BLOGS 2 THE PLANETARY REPORT C MARCH EQUINOX 2019 CONTENTS MARCH EQUINOX 2019 ADVOCATING FOR SPACE Change Comes to Washington 6 Casey Dreier assesses the sea change brought about by midterm elections in the United States—and what it might mean for space-science policy. -

2347 (Created: Tuesday, March 30, 2021 at 7:18:41 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview

JWST Proposal 2347 (Created: Tuesday, March 30, 2021 at 7:18:41 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview 2347 - A Hell of a Phase Curve: Mapping the Surface and Atmosphere of a Lava Planet K2-141b Cycle: 1, Proposal Category: GO INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Ms. Lisa Dang (PI) (CSA Member) McGill University [email protected] Prof. Nicolas B Cowan (CoI) (CSA Member) McGill University [email protected] Dr. Laura Kreidberg (CoI) (ESA Member) Max Planck Institute for Astronomy [email protected] Mr. Sebastian Zieba (CoI) (ESA Member) Max Planck Institute for Astronomy [email protected] Prof. Raymond Pierrehumbert (CoI) (ESA Member) University of Oxford [email protected]. ac.uk Dr. Mark Hammond (CoI) (US Admin CoI) University of Chicago [email protected] Giang Nguyen (CoI) (CSA Member) York University [email protected] Dr. Roxana Lupu (CoI) Bay Area Environmental Research Institute [email protected] Dr. Yamila Miguel (CoI) (ESA Member) Universiteit Leiden [email protected] Mantas Zilinskas (CoI) (ESA Member) Universiteit Leiden [email protected] OBSERVATIONS Folder Observation Label Observing Template Science Target K2-141b 1 K2-141b MIRI Low Resolution Spectroscopy (1) K2-141 ABSTRACT The CoRoT, Kepler and K2 missions have revealed a new class of planet, so-called lava planets, which have bulk densities consistent with terrestrial composition, but dayside temperatures hot enough to melt—and vaporize—rock. Of these planets, the most promising candidate for atmospheric and surface characterization is K2-141b: it has a density of 8 g/cm^3, a dayside temperature measured by Spitzer to be 2125 K, and an orbital period of 1 JWST Proposal 2347 (Created: Tuesday, March 30, 2021 at 7:18:41 PM Eastern Standard Time) - Overview 6.7 hrs around a J=9 star. -

FTIR Spectroscopy of Hot Exoplanets: a First Step in Experimental Procedure and Analysis

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2017 FTIR Spectroscopy of Hot Exoplanets: A First Step in Experimental Procedure and Analysis Heath Emmanuel Gemar As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Materials Science and Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Gemar, Heath Emmanuel, "FTIR Spectroscopy of Hot Exoplanets: A First Step in Experimental Procedure and Analysis" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3165. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3165 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FTIR SPECTROSCOPY OF HOT EXOPLANETS: A FIRST STEP IN EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE AND ANALYSIS A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Materials Science By Heath Gemar May, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Heath Emmanuel Gemar ii FTIR SPECTROSCOPY OF HOT EXOPLANETS: A FIRST STEP IN EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE AND ANALYSIS Physics, Astronomy, and Materials Science Missouri State University, May 2017 Master of Science Heath Gemar ABSTRACT In this thesis, I demonstrate how I constructed a complete experimental package to view FTIR Spectroscopy of constituents that make up hot, rocky exoplanets. -

Low Albedo Surfaces of Lava Worlds

LOW ALBEDO SURFACES OF LAVA WORLDS ZAHRA ESSACK, SARA SEAGER TESS SCIENCE CONFERENCE I HOT SUPER EARTHS LAVA-OCEAN EXOPLANETS What causes the high geometric albedos on some hot super Earths? • Rplanet < 1.6 Rearth • Tidally locked • Low pressure atmospheres (< 0.1 bar) • Substellar temperature > 850 K • Surface lava oceans due to NASA intense stellar irradiation 2 LAVA-OCEAN EXOPLANET CANDIDATES • Kepler-10 b 0.4 < Ag < 0.5 • Kepler-21 b 0.4 < Ag < 0.5 • K2-141 b 0.2 < Ag < 0.4 Demory (2014) Malavolta et al. (2018) 3 SURFACES AS A SOURCE OF HIGH ALBEDOS NASA 4 A (SIMPLE) THEORETICAL SURFACE OF A LAVA-WORLD Malavolta et al. , 2019 K2-141 b NASA Winn, 2010 5 GEOMETRIC ALBEDO OF A PLANET Malavolta et al. , 2018 K2-141 b Reflected angle: η Incidence angle ζ cos(��������) cos(���������) cos(��������) cos ��������� − α To Star Reflection coefficient To Observer Sobolev, 1975 Winn, 2010 6 MEASURING SPECULAR REFLECTION FROM QUENCHED GLASS Malavolta et al. , 2018 K2-141 b Smooth quenched glass Rough quenched glass Essack et al. (in prep) Winn, 2010 7 SPECULAR ALBEDO VS. η (ROUGH GLASS) Lab measurements of reflectionMalavolta from et al. , 2018 K2-141Incidence b Angle = quenched glass Reflected Angle (η) Fit data from lab measurements to get reflection +0.03 coefficient Ag = 0.09 function: � �, �, � – 0.01 Integrate reflection coefficient function over all latitudes and longitudes on the Substellar planet dayside point hemisphere to get = cos(latitude)cos(longitude) albedo: Ag Essack et al. (in prep) Winn, 2010 8 GEOMETRIC ALBEDO OF A COMBINATION LAVA-GLASS PLANET Malavolta et al. -

Multi-Season Optical Modulation Phased with the Orbit of the Super-Earth 55 Cancri E S

A&A 631, A129 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936066 & © ESO 2019 Astrophysics Multi-season optical modulation phased with the orbit of the super-Earth 55 Cancri e S. Sulis1, D. Dragomir2,3, M. Lendl1,4, V. Bourrier4, B. O. Demory5, L. Fossati1, P. E. Cubillos1, D. B. Guenther6, S. R. Kane7, R. Kuschnig8, J. M. Matthews9, A. F. J. Moffat10, J. F. Rowe11, D. Sasselov12, W. W. Weiss8, and J. N. Winn13 1 Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Schmiedlstraße 6, 8042 Graz, Austria e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics and Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA 4 Observatoire de l’Université de Genève, 51 chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 5 University of Bern, Center for Space and Habitability, Sidlerstraße 5, 3012 Bern, Switzerland 6 Institute for Computational Astrophysics, Department of Astronomy and Physics, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS B3H 3C3, Canada 7 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 8 Institut für Astronomie, Universität Wien Türkenschanzstrasse 17, 1180 Wien, Austria 9 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1, Canada 10 Observatoire Astronomique du Mont Mégantic, Departement de Physique, Université de Montréal C. P. 6128, Succursale: Centre-Ville, Montréal, QC H3C 3J7, Canada 11 NAS Ames Research Park, Mail Stop 244-30, Moffett Field, CA 94035-1000, USA 12 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 102138, USA 13 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, 4 Ivy Lane, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA Received 11 June 2019 / Accepted 24 September 2019 ABSTRACT Context. -

1 Curriculum Vitae

1 Curriculum Vitae 1.1 Contact McGill Space Institute 514-398-1967 (office) 3550 rue University nicolasbcowan (Skype) Montr´eal,QC H3A 2A7 [email protected] Canada msi.mcgill.ca/∼cowan 1.2 Employment & Education • McGill University, Montr´eal, QC Assistant Professor, Physics, Earth & Planetary Sciences (8/2015{) • Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO Senior Research Scientist (7/2015{12/2015) • Amherst College, Amherst, MA Assistant Professor, Physics & Astronomy (7/2014{6/2015) • Northwestern University, Evanston, IL CIERA Postdoctoral Fellow, Physics & Astronomy (9/2010{8/2014) Research Assistant Professor, Earth & Planetary Sciences (12/2012{8/2014) • University of Washington, Seattle, WA Research Associate, Astronomy (9/2009{8/2010) Ph.D. Astronomy, w/Certificate in Astrobiology 12/2009 • McGill University, Montr´eal, QC B.Sc. Physics w/First Class Honours, 2/2004 1.3 Mission Planning & Leadership • Science Team for Extrasolar Planet Polarimetry Experiment (CSA Mission Concept)1 • TESS Atmospheric Characterization Working Group • Science Team for Contribution to ARIEL Spectroscopy of Exoplanets • Science and Technology Definition Team for LUVOIR • Transiting Planet Working Group for JWST/NIRISS • Science Team for Fast Infrared Exoplanet Spectroscopy Survey Explorer 1Also known as l'Explorateur polarimetrique de plan`etesextrasolaires (EPP´ E)´ . I devised the bilingual palindrome to satisfy the CSA's peculiar acronym rules. 1 1.4 Active Grants • CSA Space Exploration Concept Study (2018{2019): $175,000 for 6 in- vestigators Extrasolar