Reading, Writing, and Privatization: the Narrative That Helped Change the Nation’S Public Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Ori Inal Document. SCHOOL- CHOICE

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 460 188 UD 034 633 AUTHOR Moffit, Robert E., Ed.; Garrett, Jennifer J., Ed.; Smith, Janice A., Ed. TITLE School Choice 2001: What's Happening in the States. INSTITUTION Heritage Foundation, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-89195-100-8 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 275p.; For the 2000 report, see ED 440 193. Foreword by Howard Fuller. AVAILABLE FROM Heritage Foundation, 214 Massachusetts Avenue, N.E., Washington, DC 20002-4999 ($12.95). Tel: 800-544-4843 (Toll Free). For full text: http://www.heritage.org/schools/. PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; Charter Schools; Educational Vouchers; Elementary Secondary Education; Private Schools; Public Schools; Scholarship Funds; *School Choice ABSTRACT This publication tracks U.S. school choice efforts, examining research on their results. It includes: current publicschool data on expenditures, schools, and teachers for 2000-01 from a report by the National Education Association; a link to the states'own report cards on how their schools are performing; current private school informationfrom a 2001 report by the National Center for Education Statistics; state rankingson the new Education Freedom Index by the Manhattan Institute in 2000; current National Assessment of Educational Progress test results releasedin 2001; and updates on legislative activity through mid-July 2001. Afterdiscussing ways to increase opportunities for children to succeed, researchon school choice, and public opinion, a set of maps and tables offera snapshot of choice in the states. The bulk of the book containsa state-by-state analysis that examines school choice status; K-12 public schools andstudents; K-12 public school teachers; K-12 public and private school studentacademic performance; background and developments; position of the governor/composition of the state legislature; and statecontacts. -

Cartoon Network in EMEA

CN in EMEA Prepared Jan 2015 The CN Brand To be funny, unexpected and stand out from the pack in a way kids can related to. ATTRIBUTES VIEWER BENEFITS Unique Expect the unexpected Fun and Funny Laugh out loud Smart To feel independent Energetic To be in the moment Current Different in a good way BRAND VALUES BRAND CORE Innovation Funny Randomness Unexpected Humour Relatable Escapism CN EMEA Distribution and Reach Distribution 133m Household 70+ Countries Dec’14 Reach 27m individuals 9.5m Kids 3.2m 15-24s 5.4m 25-34s Distribution as of November TV Data: Various peoplemeters via Techedge, all day Cartoon Network in EMEA Cartoon Network surpassed 130m Households in EMEA Cartoon Network goes from strength to strength and has grown in 5 out of 9 markets with Kids in 2014 Cartoon Network is #1 Channel in South Africa Cartoon Network is a Top 3 rating Pay TV kids Channel in 5 out of 12 markets in December 2014 . Portugal, Poland, Romania, Sweden and South Africa Adventure Time, The Amazing World of Gumball, Regular Show and Ben 10 are CN’s top ratings drivers Key Ratings Drivers across EMEA Finn, the human boy with the awesome hat, and Jake, the wise dog with At the heart of the show is Gumball who faces the trials and tribulations of magical powers, are close friends and partners in strange adventures in the any twelve-year-old kid – like being chased by a rampaging T-Rex, sleeping land of Ooo. It’s one quirky and off-beat adventure after another, as they fly rough when a robot steals his identity, or dressing as a cheerleader and doing all over the land of Ooo, saving princesses, dueling evil-doers, and doing the splits to impress the girl of his dreams. -

DOUGLAS COUNTY FAIR OFFICE Building 21 Phone (785) 841-6322 Web Address

DOUGLAS COUNTY FAIR OFFICE Building 21 Phone (785) 841-6322 web address - www.dgcountyfair.com DOUGLAS COUNTY FAIR BOARD Matthew Fishburn, President Shane Newell, Vice-President John Leslie, Secretary/Treasurer Sue Ashcraft Becky Bentley Myrna Hartford George Hunsinger Robyn Kelso Charlie Thomas Kate Welch 4-H/FFA Representatives Mike Kelso EXTENSION AGENTS Don Moler, Extension Director Marlin Bates, Horticulture Susan Johnson, Family & Consumer Sciences Kaitlyn Peine, 4-H & Youth Development Roberta Wycoff, Agriculture & Natural Resources RULES COMMITTEE Matthew Fishburn Myrna Hartford George Hunsinger John Leslie Shane Newell COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Mike Gaughan - District 1 Nancy Thellman - District 2 Jim Flory - District 3 1 Friday, July 24 Jackpot Barrel Racing 7:00 p.m. Community Building Contact Darby Zaremba, 785-766-0074 For further information Tuesday, July 28 Evening Entertainment by “ARNIE JOHNSON & THE MIDNIGHT SPECIAL” 7:00 p.m.-10:00 p.m., Stage Area Free Admission Wednesday, July 29 Naturally Nutritious Food Festival Entries accepted 6:00 - 7:00 p.m., Bldg. 21 7:00 p.m. Judging Begins (Public sampling immediately following judging) “TOUCH A TRUCK” 6:00 – 8:00 p.m., Rodeo Arena Evening Entertainment by “Loozin’ Sleep” 7:00 p.m.-10:00 p.m., Stage Area Free Admission Chef’s Challenge 5:00 – 7:30 p.m., Picnic Area Local chefs compete with local farm products. Public will get to sample recipes. Partners in this event are Douglas County Food Policy Council, K-State Research & Extension Master Food Volunteers and Master Gardeners. Thursday, July 30 DUNK for FOOD!!! 1:00 – 4:00 p.m., Black Top Area Join us on the blacktop area for the chance to “Dunk” your 4-H peers! Bring your friends and canned goods/non-perishable foods items if you would like to join in on the fun! Receive one throw per can/item or you can purchase throws with cash. -

0913-PT-A Section.Indd

Racking up sales YOUR ONLINE LOCAL Netminder Recycling auto racks big biz DAILY NEWS Hawks’ Burke settles in — See SUSTAINABLE LIFE, C1 www.portlandtribune.com — See SPORTS, B10 PortlandPTHURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2012 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDAILYTribune PAPER • WWW.PORTLANDTRIBUNE.COM • PUBLISHED THURSDAY Counties, cities hit in rebate (P)RETIREMENT’S debate Local leaders balk as lawmaker seeks cuts NEW FRONTIER to job creation fund By JIM REDDEN The Tribune An infl uential Portland-ar- ea legislator thinks local and regional governments are owed too much money from state income taxes collected as part of their econom- ic develop- ment efforts. State Sen. Ginny Burdick, who repre- sents South- west Portland and parts of BURDICK Washington County, wants the 2013 Legislature to recon- sider how the state repays cit- ies, counties and special dis- tricts that waive their property taxes to attract new jobs. The state ■ Study focuses on city’s young creatives — economic saviors or slackers has not made “We’re not any such pay- he key thing to understand about Ev- But Jones isn’t lazy in his between job pre- ments yet be- an Jones is that he doesn’t lack ambi- tirement phases. He is, in fact, usually very asking for a cause of a pos- tion. It only looks like he does. busy in his home offi ce programming comput- handout. sible legal T A Southeast Portland resident, er-controlled machines that can carve out glitch in the Jones, who moved to Portland 15 years ago, three-dimensional structures. We entered program cre- admits he isn’t ambitious in the traditional “My ambition is to be able to do things I love into a ated by the sense. -

Courier Gazette

Issued^ Tuesday THursmy Saturday he ourier azette T Entered aa Second ClueC Mall Matte, -G THREE CENTS A COPY Established January, 1846. By The Courier-Uaiette, 465 Main Ht. (Rockland, Maine, Tuesday, August 22, 1939 Volum e 9 4 ................. .Number 100. The Courier-Gazette [EDITORIAL] THREL'-TIMES-A-WEEK IS WAR COMING? “The Black Cat” Editor The situation in Europe, relative to poor, harried Poland, WM. O. FILLER Rockland Honors New Red Jacket Associate Editor grows more ominous with each passing hour. Hitler's determi PRANK A WINSLOW nation to take ever that country is apparent to all who read, and there remains to consider only the method by which he “Red Jacket Day” has come and Hutwcrlptloni S3 00 mr T’ *r payable ; Fifteen Thousand See the Parade, and Five In advance; single copies three criMa will go about It. The restive spirit which exists in Germany gone, leaving bi its trail no con Advertising rates based upon clrcula found expression in the Associated Press despatches which flicting emotions. The committee lng north on Union street to Talbot1 Uon and very reasonable. avenue, down Talbot avenue to I Thousand Visit the Ships— Notable Address NEWSPAPER HISTORY appeared In the dally newspapers on both sides of the water. in charge may rest with the as The Rockland Uaeette was estab-, The phrase "der tag" (day cf reckoning) was being spoken surance that its work was well done; Main and down Main to the Public I llshcd In 1B4C In 1114 the Courier was the public is of the unanimous opin Landing where the reviewing stand ] By State Librarian 0. -

II. Comprehension:8Pts A

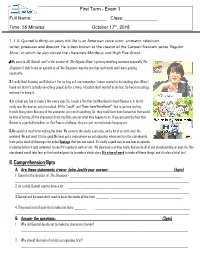

First Term - Exam 1 Full Name: _____________________________ Class: _____________ Time: 55 Minutes October 17th, 2018 1. J. G. Quintel is thirty-six years old. He is an American voice actor, animator, television writer, producer and director. He is best known as the creator of the Cartoon Network series ‘Regular Show’, in which he also voiced the characters Mordecai and High Five Ghost. 2.My name is J.G. Quintel, and I’m the creator of ‘The Regular Show’. I grew up watching cartoons especially‘The Simpsons’, I didn’t miss an episode at all.‘The Simpsons’ was the one that my friends and I were quoting constantly. 3.I really liked drawing, and I liked art. For as long as I can remember, I never wanted to be anything else. When I found out that it’s actually something people do for a living, I decided that I wanted to do that. So I went to college, and now I’m doing it. 4.In school you had to make a film every year.So, I made a film that had Mordecai in itand Benson in it. And it really was like how we acted in school. All the “uuuh!” and “Hmm, hmm!Hmm!hmm!”, that is just me and my friends being idiots.Because of the animation, you can do anything. So, they could have been human but that would be kind of boring. All the characters from my films are not what they happen to be. If you get past the fact that Benson is a gumball machine, or that Pops is a lollipop, they are just normal people hanging out. -

November-Force-Source-2019.Pdf

FoRCE SoURCE VolumeTHE 6 Issue 11 | nov. 2019 Yellowstone Snowmobile Trips Thankful Tree 10th Annual Turkey Shoot Base Holiday Parade Season Rentals Night of Shenanigans MOUNTAIN HOME AFB, IDAHO 366 FSS Commander Lt Col Allyson Strickland 366 FSS Deputy Michael Wolfe Marketing Director Shelley Turner ADVERTISE WITH US! - Magazine Advertisements Commercial Sponsorship Alexis Denoyer - 6 ft Facility Monitors Coordinator - Tabletop Acrylics - and more! Graphic Design Jessica Gibbens SPONSOR EVENTS Marketing Clerk & Private Reagan Olsen - Presence at Base Events Organization Monitor - Access to 9,000+ people - and more! Web & Social Media Miranda Baxter Interested in reaching our military & civilian community? The Force Source Magazine is prepared by the 366th Force Support Squadron Marketing Department and is an unofficial publication of the Mountain Home Please contact: AFB community. Contents are not necessarily the official views of, nor endorsed Alexis Denoyer by, the US Government, the Department of Defense, or the 366th Wing. No federal endorsement of advertisers or sponsors intended. Information in this Commercial Sponsorship Coordinator magazine is current at the time of publication. All facility programs, event hours, prices, and dates are subject to change without notice. Contact each 208-828-4519 facility for the most up to date information. 1 Contents FOOD Hackers Bistro..........................................10 Jet Stream Java.......................................10 Strikers Grill.............................................10 -

2016 Nycc 2016 Events

NYCC 2016 NYCC 2016 EVENTS THURSDAY SCHEDULE THURSDAY SCHEDULE Hammerstein Ballroom – BookCon @ NYCC – 500 Main Stage 1–D Time Room 1A02 Room 1A05 Room 1A06 Room 1A10 Room 1A18 Room 1A21 Room 1A24 Room 1B03 Time 311 W 34th St W 36th St Presented by AT&T EVENTS 10:30 AM 10:30 AM 10:45 AM 10:45 AM 11:00 AM INDEH: Native Stories 11:00 AM Body of Evidence: How and the Graphic Novel Writers Unite: Writing and Comics and STEM Education: We See Ourselves in – In Conversation with #ArtCred 11:15 AM 11:15 AM STARZ Presents: Ash vs Pitching Comic Stories A Practical Workshop Comics Ethan Hawke and Greg Evil Dead Cosplay Rule 63 Ruth Kodansha Comics Manga Panel 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM Collider Heroes Live 11:30 AM 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM 11:30 AM 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM 11:00 AM – 12:15 PM 11:45 AM 11:15 AM – 12:15 PM 11:00 AM – 12:00 PM 11:15 AM – 12:15 PM 11:15 AM – 12:15 PM 11:45 AM 12:00 PM 12:00 PM 12:15 PM 12:15 PM Teaching More than the Basics: AMC Presents Comic 25 Years of Captain End Bullying: Be a Superhero 12:30 PM Hasbro Star Wars Pairing Comics and Chapter Book Men You’re Such a Geek: Planet & The Planeteers IRL! 12:30 PM Texts in the Classroom A Guide for Teachers, MARVEL: Breaking Into Comics 12:45 PM Nat Geo’s StarTalk with Neil Funimation Industry Panel 12:15 PM – 1:15 PM A World Unlike Any 12:15 PM – 1:15 PM Students, and Parents to 12:15 PM – 1:15 PM 12:15 PM – 1:15 PM the Marvel Way 12:45 PM deGrasse Tyson: Everything 12:15 PM – 1:15 PM You Ever Need to Know Other: The Importance Help Cope with Bullying 12:30 PM – 1:30 -

Floor Show Highlights Dc Semi-Form

FLOOR SHOW HIGHLIGHTS DC SEMI-FORM, PROFITS FROM DSG DANCE AT SCOTTISH RITE TEMPLE WILL GO TO CAMPUS RED CROSS MIT Profits derived from Delta Sigma Gcannsass7 annual winter semi-formal dance, to be held Saturday night at the Scottish Rite Temple, will be given to the Red Cross, it was announced today. At press time there was still uncertainty as to whether it would be possible to have their fraternity sweehecrrt, Linda Dctrnell, on hand as guest of honor for the evening. Ed Kin- caid, program chairman, announces that an answer to a tele- ircm2 sent Kiss Darnell is still pending, but should reach him VOL. XXXI §AN JOSE, CALIFORNIA, FRIDAY, MARCH 5, 1943 Number 95 soon. Last word heard from the famous star was that she is No! Pleasy Yank scheduled to go on a 44-city tour, but there is still uncertainty Anything But alto the date of her leaving. In That freshmen Celtbrate Tonight At the event that she should be able Distract, side step, bend Nippy to make the social event, she an- PEV Cutters Will backward over knee, and wham- nounced that she would be delight- bol And Jap soldier loses more Lyric Theater-Forlast_Party__ ed "to wear out two pair of shoes Be Reported Next than face and wishes he had com- 10 Lig (lancing with her loving fraternity mitted hari-karl ininutes be- brothers." Week - - Pitman fore. Of Quarter; Dance Begins At 8 A question concerning the legal- "Beginning of the end" came for You might have guessed itthe Tonight, freshmen will celebrate their last class party of PEV cutters yesterday. -

Yoichi Hiraoka: His Artistic Life and His Influence on the Art Of

YOICHI HIRAOKA: HIS ARTISTIC LIFE AND HIS INFLUENCE ON THE ART OF XYLOPHONE PERFORMANCE Akiko Goto, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2013 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Eugene M. Corporon, Committee Member Christopher Deane, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Goto, Akiko. Yoichi Hiraoka: His Artistic Life and His Influence on the Art of Xylophone Performance. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2013, 128 pp., 31 figures, bibliography, 86 titles. Yoichi Hiraoka was an amazing Japanese xylophone player who had significant influence on the development of the xylophone as a solo instrument. The purpose of this dissertation is to collect and record evidence of Mr. Hiraoka, to examine his distinguished efforts to promote the xylophone, to investigate his influences on keyboard percussion literature, and to contribute to the development of the art of keyboard percussion performance as a whole. This dissertation addresses Yoichi Hiraoka’s artistic life, his commissioned pieces, and his influence on the art of xylophone performance. Analyses of two of his most influential commissioned works, Alan Hovhaness’ Fantasy on Japanese Wood Prints and Toshiro Mayuzumi’s Concertino for Xylophone Solo and Orchestra, are also included to illustrate the art of the xylophone, and to explain why Hiraoka did not play all of his commissioned works. Copyright 2013 by Akiko Goto ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to sincerely thank my committee members, Mark Ford, Eugene Corporon, and Christopher Deane, for their continuous guidance and encouragement. -

Cartoons Are No Laughing Matter

SPECIAL REPORT July 2011 Cartoons Are No Laughing Matter Sex, Drugs and Profanity on Primetime Animated Programs Cartoons Are No Laughing Matter: Sex, Drugs and Profanity on Primetime Animated Programs July 2011 Our work is often inspired by the passion and compassion of others. A special thank you to the following individuals and foundations for their generous support. Donald and Michele D’Amour William E. Simon Foundation Mathile Family Foundation Stuart Family Foundation Mr. & Mrs. T. Bondurant French 2 Cartoons Are No Laughing Matter: Sex, Drugs and Profanity on Primetime Animated Programs July 2011 FOR MEDIA INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Megan Franko CRC Public Relations (703) 859-5054 or Liz Krieger CRC Public Relations (703) 683-5004, ext. 120 www.ParentsTV.org 3 Cartoons Are No Laughing Matter: Sex, Drugs and Profanity on Primetime Animated Programs July 2011 CONTENTS I. Executive Summary 5 II. Network Report Card 9 III. Introduction 10 IV. About the Networks 11 V. Methodology 12 VI. A Description of the TV Rating System 13 VII. Study Findings 13 VIII. Conclusion 17 IX. Content Examples 19 X. Data Tables 26 XI. References 4 Cartoons Are No Laughing Matter: Sex, Drugs and Profanity on Primetime Animated Programs July 2011 C artoons Are No Laughing Matter Sex, Drugs and Profanity on Primetime Animated Programs The present study not only reveals what kids are seeing on cartoons today, it also reveals what networks and advertisers are marketing to children and teens while they are watching. Executive Summary The television industry is often criticized for the amount of sex, violence and profanity it airs. -

We, the Judges: the Legalized Subject and Narratives of Adjudication in Reality Television, 81 UMKC L. Rev. 1 (2012)

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2012 We, the Judges: The Legalized Subject and Narratives of Adjudication in Reality Television, 81 UMKC L. Rev. 1 (2012) Cynthia D. Bond John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Judges Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Cynthia D. Bond, We, the Judges: The Legalized Subject and Narratives of Adjudication in Reality Television, 81 UMKC L. Rev. 1 (2012). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/331 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "WE, THE JUDGES": THE LEGALIZED SUBJECT AND NARRATIVES OF ADJUDICATION IN REALITY TELEVISION CYNTHIA D. BOND* "Oh how we Americans gnash our teeth in bitter anger when we discover that the riveting truth that also played like a Sunday matinee was actually just a Sunday matinee." David Shields, Reality Hunger "We do have a judge; we have two million judges." Bethenny Frankel, The Real Housewives of New York City ABSTRACT At first a cultural oddity, reality television is now a cultural commonplace. These quasi-documentaries proliferate on a wide range of network and cable channels, proving adaptable to any audience demographic. Across a variety of types of "reality" offerings, narratives of adjudication- replete with "judges," "juries," and "verdicts"-abound.