Foraging Behaviour and Nectar Use in Adult Large Copper Butterflies, Lycaena Dispar (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Support for Successful Implementation of the Natura 2000 Network

Scientific support for successful implementation of the Natura 2000 network Focus Area B Guidance on the application of existing scientific approaches, methods, tools and knowledge for a better implementation of the Birds and Habitat Directives Environment FOCUS AREA B SCIENTIFIC SUPPORT FOR SUCCESSFUL i IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATURA 2000 NETWORK Imprint Disclaimer This document has been prepared for the European Commis- sion. The information and views set out in the handbook are Citation those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the Van der Sluis, T. & Schmidt, A.M. (2021). E-BIND Handbook (Part B): Scientific support for successful official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not implementation of the Natura 2000 network. Wageningen Environmental Research/ Ecologic Institute /Milieu guarantee the accuracy of the data included. The Commission Ltd. Wageningen, The Netherlands. or any person acting on the Commission’s behalf cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information Authors contained therein. Lead authors: This handbook has been prepared under a contract with the Anne Schmidt, Chris van Swaay (Monitoring of species and habitats within and beyond Natura 2000 sites) European Commission, in cooperation with relevant stakehold- Sander Mücher, Gerard Hazeu (Remote sensing techniques for the monitoring of Natura 2000 sites) ers. (EU Service contract Nr. 07.027740/2018/783031/ENV.D.3 Anne Schmidt, Chris van Swaay, Rene Henkens, Peter Verweij (Access to data and information) for evidence-based improvements in the Birds and Habitat Kris Decleer, Rienk-Jan Bijlsma (Guidance and tools for effective restoration measures for species and habitats) directives (BHD) implementation: systematic review and meta- Theo van der Sluis, Rob Jongman (Green Infrastructure and network coherence) analysis). -

Superior National Forest

Admirals & Relatives Subfamily Limenitidinae Skippers Family Hesperiidae £ Viceroy Limenitis archippus Spread-wing Skippers Subfamily Pyrginae £ Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus clarus £ Dreamy Duskywing Erynnis icelus £ Juvenal’s Duskywing Erynnis juvenalis £ Northern Cloudywing Thorybes pylades Butterflies of the £ White Admiral Limenitis arthemis arthemis Superior Satyrs Subfamily Satyrinae National Forest £ Common Wood-nymph Cercyonis pegala £ Common Ringlet Coenonympha tullia £ Northern Pearly-eye Enodia anthedon Skipperlings Subfamily Heteropterinae £ Arctic Skipper Carterocephalus palaemon £ Mancinus Alpine Erebia disa mancinus R9SS £ Red-disked Alpine Erebia discoidalis R9SS £ Little Wood-satyr Megisto cymela Grass-Skippers Subfamily Hesperiinae £ Pepper & Salt Skipper Amblyscirtes hegon £ Macoun’s Arctic Oeneis macounii £ Common Roadside-Skipper Amblyscirtes vialis £ Jutta Arctic Oeneis jutta (R9SS) £ Least Skipper Ancyloxypha numitor Northern Crescent £ Eyed Brown Satyrodes eurydice £ Dun Skipper Euphyes vestris Phyciodes selenis £ Common Branded Skipper Hesperia comma £ Indian Skipper Hesperia sassacus Monarchs Subfamily Danainae £ Hobomok Skipper Poanes hobomok £ Monarch Danaus plexippus £ Long Dash Polites mystic £ Peck’s Skipper Polites peckius £ Tawny-edged Skipper Polites themistocles £ European Skipper Thymelicus lineola LINKS: http://www.naba.org/ The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination http://www.butterfliesandmoths.org/ in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national -

New Data on Little Known and Rare Species Athamanthia Japhetica (Nekrutenko Et Effendi, 1983) (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) from the Caucasus

Евразиатский энтомол. журнал 18(3): 213–216 © EUROASIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL doi: 10.15298/euroasentj.18.3.12 JOURNAL, 2019 New data on little known and rare species Athamanthia japhetica (Nekrutenko et Effendi, 1983) (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) from the Caucasus Íîâûå ñâåäåíèÿ î ìàëîèçó÷åííîì è ðåäêîì âèäå Athamanthia japhetica (Nekrutenko et Effendi, 1983) (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) íà Êàâêàçå D.V. Morgun Ä.Â. Ìîðãóí Moscow Centre of Environmental Education, Regional Research and Tourism, Odesskaya Str. 12A, Moscow 117303 Russia. E-mail: [email protected]. Московский центр экологии, краеведения и туризма, ул. Одесская 12А, Москва 117303 Россия. Key words: Athamanthia japhetica, Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae, distribution, Georgia, fauna. Ключевые слова: Athamanthia japhetica, Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae, распространение, Грузия, фауна. Abstract. New data on the distribution and ecology of the species distribution was treated as Apsheron peninsu- rare Lycaenid species Athamanthia japhetica (Nekrutenko et la in Caspian area of Azerbaijan [Tuzov et al., 2000]. In Effendi, 1939 (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) in the Central Cau- 2012 and 2013, V.V. Tikhonov and V.A. Lukhtanov found casus are presented. A comparison of the new material with the population of A. japhetica near the type locality in the specimens of the former known populations is described. the Tugchai valley, 30 km SW Kilyazy village, and near Резюме. Представлены новые сведения о распростра- Shirvan station. нении и экологии редкого вида голубянок (Athamanthia New population of A. japhetica in Georgia. Until japhetica (Nekrutenko et Effendi, 1983) (Lepidoptera, now, A. japhetica was treated as a species of Caspian Lycaenidae) в центральной части Кавказа. Описано срав- area of Eastern Azerbaijan, known only by two recently нение особей с особями ранее известных популяций вида. -

Catalogue 294 Recent Acquisitions CATALOGUE 294 Catalogue 294

ANTIQUARIAAT JUNK ANTIQUARIAAT Antiquariaat Junk Catalogue 294 1 Recent Acquisitions CATALOGUE CATALOGUE 294 Catalogue 294 Old & Rare Books Recent Acquisitions 2016 121 Levaillant Catalogue 294 Recent Acquisitions Antiquariaat Junk B.V. Allard Schierenberg and Jeanne van Bruggen Van Eeghenstraat 129, NL-1071 GA Amsterdam The Netherlands Telephone: +31-20-6763185 Telefax: +31-20-6751466 [email protected] www.antiquariaatjunk.com Natural History Booksellers since 1899 Please visit our website: www.antiquariaatjunk.com with thousands of colour pictures of fine Natural History books. You will also find more pictures of the items displayed in this catalogue. Items 14 & 26 sold Frontcover illustration: 88 Gessner Backcover illustration: 121 Levaillant GENERAL CONDITIONS OF SALE as filed with the registry of the District Court of Amsterdam on No- vember 20th, 1981 under number 263 / 1981 are applicable in extenso to all our offers, sales, and deliveries. THE PRICES in this catalogue are net and quoted in Euro. As a result of the EU single Market legisla- tion we are required to charge our EU customers 6% V.A.T., unless they possess a V.A.T. registration number. Postage additional, please do not send payment before receipt of the invoice. All books are sold as complete and in good condition, unless otherwise described. EXCHANGE RATES Without obligation: 1 Euro= 1.15 USD; 0.8 GBP; 124 JPY VISITORS ARE WELCOME between office hours: Monday - Friday 9.00 - 17.30 OUR V.A.T. NUMBER NL 0093.49479B01 134 Meyer 5 [1] AEMILIANUS, J. Naturalis de Ruminantibus historia Ioannis Aemy- liani... Venetiis, apaud Franciscum Zilettum, 1584. -

References Cited

References Cited Ballmer, G. and G.Pratt. 1988. A survey of the last instar larvae of the Lycaenidae of California. J. Res. Lep. 27: 1-81. Claibome, W. 1997. Authorities net butterfly poacher at National Park. Washington Post August 2, 1997. Clark, D.L., Finley, K.K. and Ingersoll, C.A. 1993. Status Report for Erigeron decumbens var. decumbens. Prepared for the Conservation Biology Program, Oregon Department of Agriculture, Salem, OR. 55 pp. Clarke, S.A. 1905. Pioneer Days of Oregon History Vol. I, pp 89-90. J.K. Gill Co., Portland, OR. Collins, N.M. and M.G. Morris. 1985. Threatened Swallowtail butterflies of the world. IUCN Red Data Book. Gland, Switzerland. 401pp. Cronquist, Arthur. 1947. Revision of the North American species of Erigeron, north of Mexico. Brittonia 6: 173-1 74 Dornfeld, E. J. 1980. Butterflies of Oregon. Timber Press, Forest Grove, Oregon. Douglas, D. 1972. The Oregon Journals of David Douglas of His Travels and Adventures Among the Traders and Indians in the Columbia, Willamette, and Snake River Regions During the Years 1825, 1826, and 1827. The Oregon Book Society, Ashland, OR. Downey, J. C. 1962. Myrmecophily in Plebejus (Icaricia) icarioides (Lepid: Lycaenidae). Net. News 73:57-66. Downey, J.C. 1975. Genus Pegasus Klux. Pp. 337-35 1 IN W. H. Howe,ed., The butterflies of North America. Doubleday and Co., Garden City, New York. Duffey, E. 1968. Ecological studies on the large copper butterflies, lycaena dispar batayus, at Woodwalton Fen NNR, Huntingdonshire. J. Appl. Ecol. 5:69-96. Franklin, J.F. and C.T. Dyrness. -

BUTTERFLIES of the Trails and Fields at Rice Creek Field Station State University of New York at Oswego

SNEAK A PEEK INSIDE... A Guide to the BUTTERFLIES of the Trails and Fields at Rice Creek Field Station State University of New York at Oswego Michael Holy - August 2010 Compton Tortoise Shell (Nymphalis vau-album) Nymphalidae Description: [L] Various shades of brown with black and white markings above. Compton Tortoise Shell Underside is a dark gray with a silver comma on its hindwing. (Nymphalis vau-album) Interesting Fact: This species is known to aestivate (“hibernate”) during the hottest Nymphalidae weeks of summer. Best Observed: Area around Herb Garden, wooded Red Trail between the upper field and parking lot. Milbert’s Tortoise Shell (Nymphalis milberti) Nymphalidae Description: [M] Orange bands across black wings above with blue spots along edge of hindwing. Milbert’s Tortoise Shell Interesting Fact: In flight this species is easily mistaken for a Comma or Question (Nymphalis milberti) Nymphalidae Mark despite its wing colors. Best Observed: Herb Garden, Beaver Meadow on Green Trail, and open fields nectaring Milkweed, Joe-pye Weed, and Purple Loosestrife, June through August. Mourning Cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) Nymphalidae Description: [L] Wings above are a rich brown black color bordered with blue spots and a pale yellow band. Mourning Cloak Interesting Fact: A true hibernator, this species can be observed in wood settings on (Nymphalis antiopa) Nymphalidae warm early spring days with snow still on the ground. Best Observed: Woods in spring, fields and all trails in summer, April through early November . White Admiral ( Limenitis arthemis) Nymphalidae Description: [L] White bands interrupt a black/brown wing color. White Admiral Interesting Fact: A variant, the Red-spotted Purple, lacks the white wing bands, (Limenitis arthemis) Nymphalidae substituting a blue green metallic hue. -

State of Nature Report

STATE OF NATURE Foreword by Sir David Attenborough he islands that make up the The causes are varied, but most are (ButterflyHelen Atkinson Conservation) United Kingdom are home to a ultimately due to the way we are using Twonderful range of wildlife that our land and seas and their natural is dear to us all. From the hill-walker resources, often with little regard for marvelling at an eagle soaring overhead, the wildlife with which we share them. to a child enthralled by a ladybird on The impact on plants and animals has their fingertip, we can all wonder at been profound. the variety of life around us. Although this report highlights what However, even the most casual of we have lost, and what we are still observers may have noticed that all is losing, it also gives examples of how not well. They may have noticed the we – as individuals, organisations, loss of butterflies from a favourite governments – can work together walk, the disappearance of sparrows to stop this loss, and bring back nature from their garden, or the absence of where it has been lost. These examples the colourful wildflower meadows of should give us hope and inspiration. their youth. To gain a true picture of the balance of our nature, we require We should also take encouragement a broad and objective assessment of from the report itself; it is heartening the best available evidence, and that is to see so many organisations what we have in this groundbreaking coming together to provide a single State of Nature report. -

Updated National Strategy for the Protection of Biodiversity to 2020

Updated National Strategy for the Protection of Biodiversity to 2020 Slovak Republic 2014 Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Global framework for the protection of biodiversity and its implementation in Slovakia .................................. 3 Biodiversity loss and its consequences........................................................................................................... 4 Failure to meet the target to reduce or halt biodiversity loss by 2010 ............................................................. 5 Setting a new target to be achieved by 2020 on a global and European scale............................................... 5 The role of the Updated National Strategy for the Protection of Biodiversity to 2020 ..................................... 6 2. Long-term vision and further consideration of the Updated National Strategy for the Protection of Biodiversity to 2020 ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 Long-term vision for the protection of biodiversity in Slovakia to 2050............................................................ 8 Basis for the Updated National Strategy for the Protection of Biodiversity to 2020......................................... 8 3. Evaluation of the current status of the biodiversity protection in Slovakia...................................................... -

7-1 1 May 2007

Volume 7 Number 1 1 May 2007 The Taxonomic Report OF THE INTERNATIONAL LEPIDOPTERA SURVEY A Description of a New Subspecies of Lycaena phlaeas (Lycaenidae: Lycaeninae) from Montana, United States, With a Comparative Study of Old and New World Populations Steve Kohler 125 Hillcrest Loop, Missoula, Montana 59803 United States of America Abstract: The Palaearctic, Oriental and Ethiopian Region subspecies of Lycaena phlaeas are briefly discussed. A more detailed account of the North American subspecies is presented, and a new subspecies, L. p. weberi, from the Sweet Grass Hills, Montana is described. The possibility that the eastern United States subspecies hypophlaeas was introduced from the Old World is discussed; however no conclusion can be reached with certainty. The relationship between Old World and New World subspecies of L. phlaeas is discussed. Evidence presented supports the treatment of New World populations as subspecies of L. phlaeas. Additional key words: Polygonaceae, Rumex acetosella, R. acetosa, R. crispus, Oxyria digyna. INTRODUCTION Lycaena phlaeas (Linnaeus, 1761) is a widespread species with subspecies in Europe, North Africa, Arabia, northern Asia, Japan, North America and tropical Africa. The nominate subspecies occurs in northern Europe (Ackery et al., 1995). Shields & Montgomery (1966) mentioned that European texts list Polygonaceae (Rumex and Polygonum) as larval foodplants for L. phlaeas subspecies. Flight period is April to November, in one to four generations, depending on local conditions; over-wintering is in the larval stage (Tuzov, 2000). Bridges (1988) listed 19 subspecies in his catalogue, not including the North American ones. Miller and Brown (1981) listed five subspecies for North America. Ford (1924) attempted to cover the world-wide geographic races of L. -

Withymead Butterfly and Dragonfly Survey 2018

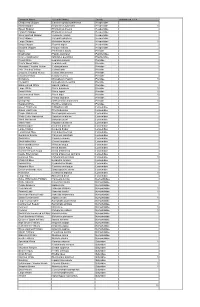

Common Name Scientific Name Family Withymead 2018 Chequered Skipper Carterocephalus palaemon Hesperiidae Small Skipper Thymelicus sylvestris Hesperiidae 1 Essex Skipper Thymelicus lineola Hesperiidae Lulworth Skipper Thymelicus acteon Hesperiidae Silver-spotted Skipper Hesperia comma Hesperiidae Fiery Skipper Hylephilla phyleus Hesperiidae Large Skipper Ochlodes faunus Hesperiidae 1 Dingy Skipper Erynnis tages Hesperiidae Grizzled Skipper Pyrgus malvae Hesperiidae Apollo Parnassius apollo Pieridae Swallowtail Papilio machaon Papilionidae Scarce Swallowtail Iphiclides podalirius Papilionidae Wood White Leptidea sinapis Pieridae Réal's Wood White Leptidea reali Pieridae Moorland Clouded Yellow Colias palaeno Pieridae Pale Clouded Yellow Colias hyale Pieridae Berger's Clouded Yellow Colias alfacariensis Pieridae Clouded Yellow Colias croceus Pieridae Brimstone Gonepteryx rhamni Pieridae 1 Cleopatra Gonepteryx cleopatra Pieridae Black-veined White Aporia crataegi Pieridae Large White Pieris brassicae Pieridae 1 Small White Pieris rapae Pieridae 1 Green-veined White Pieris napi Pieridae 1 Bath White Pontia daplidice Pieridae Orange-tip Anthocharis cardamines Pieridae 1 Dappled White Euchloe simplonia Pieridae Green Hairstreak Callophrys rubi Lycaenidae Brown Hairstreak Thecla betulae Lycaenidae Purple Hairstreak Neozephyrus quercus Lycaenidae White Letter Hairstreak Satyrium w-album Lycaenidae Black Hairstreak Satyrium pruni Lycaenidae Slate Flash Rapala schistacea Lycaenidae Small Copper Lycaena phlaeas Lycaenidae Large Copper Lycaena dispar -

The African Copper Connection

The African copper connection Rienk de Jong & Karen van Dorp Apart from their colourful appearance, Copper butterflies are intriguing because of their highly National Museum of Natural History Naturalis disjunct distribution. Almost all species occur in PO Box 9517 the Holarctic region, but a few are found isolated 2300 RA Leiden in the Southern Hemisphere. To learn more about The Netherlands the interrelationship of the southern taxa and [email protected] their distribution history, an analysis of the phy- logeny of the group was carried out. Although morphological characters are sufficient to diagno- se the species, they proved insufficient to build a phylogeny on. Theref o r e, we had recourse to mo- lecules, using two genes. Here we report on the represented in Africa south of the Sahara by L. phlaeas (s o u t h results with reg a r d to the African rep re s e n t a t i v e s . to Malawi) and two species in South Africa, L. orus Stoll, 1780, and L. clarki Dickson, 1971, and surprisingly in New Zealand Entomologische Berichten 66(4): 124-129 by four species. The other tribe of the subfamily, Heliophorini (Bozano & Weidenhoffer 2001), also has a remarkable distribu- tion, with one genus in the Oriental region, one in Papua New Key words: copper butterflies, Africa, DNA, phylogeny, dis- Guinea and one in Guatemala. To understand these distribu- tribution tions we need to know the phylogeny of the group. In this paper we focus on the question whether the South African taxa Search for the phylogeny of copper butterflies are closely related to the other taxon in Subsaharan Africa, L. -

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation As Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation as Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest Prepared by: Wildlife Biologists and Natural Resources Specialist Regional Office, Inyo National Forest, and Washington Office Enterprise Program for: Inyo National Forest August 2018 1 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992.