Mike Koehler, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Jurisprudence Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooklyn Law Notes| the MAGAZINE of BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL SPRING 2018

Brooklyn Law Notes| THE MAGAZINE OF BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL SPRING 2018 Big Deals Graduates at the forefront of the booming M&A business SUPPORT THE ANNUAL FUND YOUR CONTRIBUTIONS HELP US • Strengthen scholarships and financial aid programs • Support student organizations • Expand our faculty and support their nationally recognized scholarship • Maintain our facilities • Plan for the future of the Law School Support the Annual Fund by making a gift TODAY Visit brooklaw.edu/give or call Kamille James at 718-780-7505 Dean’s Message Preparing the Next Generation of Lawyers ROSPECTIVE STUDENTS OFTEN ask about could potentially the best subject areas to focus on to prepare for qualify you for law school. My answer is that it matters less what several careers.” you study than how you study. To be successful, it Boyd is right. We is useful to study something that you love and dig made this modest Pdeep in a field that best fits your interests and talents. Abraham change in our own Lincoln, perhaps America’s most famous and respected lawyer, admissions process advised aspiring lawyers: “If you are resolutely determined to encourage to make a lawyer of yourself, the thing is more than half done highly qualified students from diverse academic and work already…. Get the books, and read and study them till you backgrounds to apply and pursue a law degree. Our Law understand them in their principal features; and that is the School long has attracted students who come to us with deep main thing.” experience and study in myriad fields. Currently, more than Today, with so much information and knowledge available 60 percent of our applicants have one to five years of work in cyberspace, Lincoln’s advice is more relevant than ever. -

Nysba Spring 2017 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2017 | VOL. 23 | No. 1 Commercial and Federal Litigation Section Newsletter A publication of the Commercial and Federal Litigation Section of the New York State Bar Association www.nysba.org/ComFed Upcoming Commercial and Federal Litigation Section Events and Co-Sponsored Events Thursday, March 30, 2017 Legal Ethics in the Digital Age: Practical Strategies for Using Technology Ethically in Your Practice Live CLE Program and Webcast | 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. | Executive Conference Center | NYC Renowned speakers on ethics, social media and electronic discovery. Learn the ins and outs of protecting privilege in elec- tronic communications. Speakers will also cover managing records in the cloud and organizing client fi les. A panel discus- sion on the do’s and don’ts of attorney social media use and advice to clients. 4.0 MCLE Credits in Ethics. Co-Sponsored by the Commercial and Federal Litigation Section, the Committee on CLE and the Law Practice Management Committee. Basic Lessons on Ethics and Civility 2017 (held in 5 locations) Live CLE Program and Webcast | 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Wednesday, April 5, 2017 in NYC | Friday, April 7, 2017 in Albany | Friday, April 7, 2017 in Rochester Friday, April 28, 2017 | in Amherst | Friday, April 28, 2017 in Melville A sound ethical compass and a civil and professional demeanor are the hallmarks of successful and respected attorneys in all areas of practice. This four hour program will provide attendees with an update on developments in the area of attorney eth- ics, including the most recent case law. -

AMERICA's CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 11

t I l AlLY r .... )k.fl ~FS A Ot:l ) lO~Ol R.. Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W. Yale-Loehr • M I GRAT i o~]~In AMERICA'S CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity after September 11 .. AUTHORS Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W . Yale-Loehr MPI gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton in the preparation of this report. Copyright © 2003 Migration Policy Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Migration Policy Institute. Migration Policy Institute Tel: 202-266-1940 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300 Fax:202-266-1900 Washington, DC 20036 USA www.migrationpolicy.org Printed in the United States of America Interior design by Creative Media Group at Corporate Press. Text set in Adobe Caslon Regular. "The very qualities that bring immigrants and refugees to this country in the thousands every day, made us vulnerable to the attack of September 11, but those are also the qualities that will make us victorious and unvanquished in the end." U.S. Solicitor General Theodore Olson Speech to the Federalist Society, Nov. 16, 2001. Mr. Olson's wife Barbara was one of the airplane passengers murdered on September 11. America's Challenge: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 1 1 Table of Contents Foreword -

The Changing Shape of Federal Civil Pretrial Practice: the Disparate Impact on Civil Rights and Employment Discrimination Cases

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship 1-2010 The hC anging Shape of Federal Civil Pretrial Practice: The Disparate Impact on Civil Rights and Employment Discrimination Cases Elizabeth M. Schneider Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, and the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Recommended Citation 158 U. Pa. L. Rev. 517 (2009-2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLE THE CHANGING SHAPE OF FEDERAL CIVIL PRETRIAL PRACTICE: THE DISPARATE IMPACT ON CIVIL RIGHTS AND EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION CASES ELIZABETH M. SCHNEIDERt INTRO DUCTIO N ................................................................................ 518 I. THE CHANGING NATURE OF CIVIL PRETRIAL PRACTICE IN THE FEDERAL COURTS ........................................ 523 A . P leading.......................................................................... 527 B. Summary Judgment, Iqbal, and Scott .............................. 537 C . D aubert .........................................................................55 1 II. IMPLICATIONS FOR FEDERAL CIVIL LITIGATION ...................... 556 III. W HY Is THIS HAPPENING? ........................................................ 562 IV. CORRECTING THE IMPACT ........................................................ 569 Rose L. Hoffer -

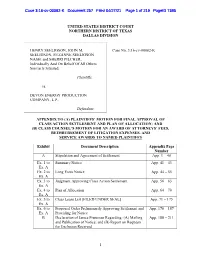

Appendix to Plaintiffs' Motion for Final Approval of Settlement, Plan of Allocation, and Attorneys' Fees

Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 1 of 219 PageID 7385 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION HENRY SEELIGSON, JOHN M. Case No. 3:16-cv-00082-K SEELIGSON, SUZANNE SEELIGSON NASH, and SHERRI PILCHER, Individually And On Behalf Of All Others Similarly Situated, Plaintiffs, vs. DEVON ENERGY PRODUCTION COMPANY, L.P., Defendant. APPENDIX TO (A) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR FINAL APPROVAL OF CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT AND PLAN OF ALLOCATION; AND (B) CLASS COUNSEL’S MOTION FOR AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES, REIMBURSEMENT OF LITIGATION EXPENSES, AND SERVICE AWARDS TO NAMED PLAINTIFFS Exhibit Document Description Appendix Page Number A Stipulation and Agreement of Settlement App. 1 – 40 Ex. 1 to Summary Notice App. 41 – 43 Ex. A Ex. 2 to Long Form Notice App. 44 – 55 Ex. A Ex. 3 to Judgment Approving Class Action Settlement App. 56 – 63 Ex. A Ex. 4 to Plan of Allocation App. 64 – 70 Ex. A Ex. 5 to Class Lease List [FILED UNDER SEAL] App. 71 – 175 Ex. A Ex. 6 to Proposed Order Preliminarily Approving Settlement and App. 176 – 187 Ex. A Providing for Notice B Declaration of James Prutsman Regarding: (A) Mailing App. 188 – 211 and Publication of Notice; and (B) Report on Requests for Exclusion Received 1 Case 3:16-cv-00082-K Document 257 Filed 04/27/21 Page 2 of 219 PageID 7386 C Declaration of Joseph H. Meltzer in Support of Class App. 212 – 265 Counsel’s Motion for An Award of Attorneys’ Fees Filed on Behalf of Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check LLP D Declaration of Brad Seidel in Support of Class App. -

Scheindlin, Hon. Shira

Judicial Profile Hon. Shira Scheindlin Senior Judge, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York by Philip R. Schatz udge Shira Scheindlin is a prodigious worker, even by the power-driven standards of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Her law clerks are expected to Jwork 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. every weekday and six hours on weekends, and to eat lunch at their desks.1 She solicits overflow work from other judges. She is a prolific writer and lecturer. She exercises an hour each day. Philip R. Schatz is a partner at the New She walks across the Brooklyn Bridge and back, every York law firm Wrobel day, whatever the weather. Markham Schatz Kaye & “She has a remarkable work ethic,” says former law Fox LLP. He is a Second clerk Ester Murdukhayeva, now a litigation associate Circuit vice president at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. for the FBA and a member of The Federal “Her docket is always full,” says former law clerk Lawyer’s editorial board. Elisha Barron, now a litigation associate at Susman Any opinions expressed Godfrey. in this profile are his “Nobody works harder,” says former law clerk own and not those of the Rachel G. Skaistis, now a litigation partner at Cravath, FBA or his firm. Swaine & Moore. “My husband was so happy when my the judge, and I have to decide. If I get reversed, I get clerkship was over and I went back to Cravath.” If you reversed.’” know Cravath, you know that’s saying something. -

Brooklyn Law Notes Law Brooklyn the Passion of Pips Pips of Passion The

Brooklyn Law Notes THE MAGAZINE OF BROOKLYN LAW SCHOOL | FALL 2016 Brooklyn Law Notes FALL 2016 The Passion of PipS Race, Technology, and New Faculty Build Fellows at Work the Future of Policing on Excellence Brooklyn Law Notes Dean’s Message Vol. 21, No. 2 We the People Editor-in-Chief Clorinda Valenti Director of Communications Managing Editor Kaitlin Ugolik Class Notes Editor Andrea Polci Associate Director of Alumni Relations Faculty Notes Editor John Mackin Public Relations Manager Contributors Dominick DeGaetano Jesse Sherwood Andrea Strong Peggy Swisher Art Director Ron Hester Photographers Todd France Ron Hester Will O’Hare Peter Tannenbaum Joe Vericker Printer Allied Printing Contact us n a beautiful sun-splashed September day in We welcome letters and comments about Washington, D.C., it was an exquisitely memorable articles in Brooklyn Law Notes. We will experience to be part of the large crowd celebrat- consider reprinting brief submissions ing the opening of the new Smithsonian National in print issues and on our website. OMuseum of African American History and Culture. Words alone tel: 718-780-7966 cannot capture the museum’s full impact, from the metal lattice e mail: [email protected] exterior walls that recall iconic figures once serving as symbolic Web: brooklaw.edu guardians protecting African villages, to the large welcoming m ailing address front porch and the exhibition halls filled with artifacts, art, and Managing Editor Brooklyn Law Notes displays that are vibrant, moving, and often painful and horri- 250 Joralemon Street fying reminders of the struggles, as well as contributions and Brooklyn, New York 11201 triumphs, of African Americans. -

How the Southern District of New York's "Related Cases" Rule Shaped Stop-And-Frisk Rulings

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 19 2014 The Danger of Nonrandom Case Assignment: How the Southern District of New York's "Related Cases" Rule Shaped Stop-and-Frisk Rulings Katherine A. Macfarlane Louisiana State University Paul M. Hebert Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Courts Commons, Fourth Amendment Commons, Judges Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Katherine A. Macfarlane, The Danger of Nonrandom Case Assignment: How the Southern District of New York's "Related Cases" Rule Shaped Stop-and-Frisk Rulings, 19 MICH. J. RACE & L. 199 (2014). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol19/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DANGER OF NONRANDOM CASE ASSIGNMENT: HOW THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK’S “RELATED CASES” RULE SHAPED STOP-AND-FRISK RULINGS Katherine A. Macfarlane* The Southern District of New York’s local rules are clear: “[A]ll active judges . shall be assigned substantially an equal share of the categories of cases of the court over a period of time.” Yet for the past fourteen years, Southern District Judge Shira Scheindlin has been granted near-exclusive jurisdiction over one cate- gory of case: those involving wide-sweeping constitutional challenges to the New York Police Department’s (NYPD) stop-and-frisk policies. -

Women in the Courtroom Symposium: Judges, In-House Counsel and Law Firms As Change Agents

Women’s Initiative Network of Reed Smith Women in the Courtroom Symposium: Judges, in-house counsel and law firms as change agents Agenda and speaker biographies April 17, 2018 Agenda | Tuesday, April 17, 2018 Sky Philadelphia, Three Logan Square, 1717 Arch Street, 51st Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19103 12:30 – 1:00 p.m. Registration and lunch Welcome address • Sandy Thomas, Global Managing Partner, Reed Smith 1:00 – 1:45 p.m. • Sara Begley, Partner, Global Chair – Women’s Initiative Network, Reed Smith Keynote: Diversity among practicing attorneys and in ADR • Hon. Shira Scheindlin, U.S. District Judge (ret.) and AAA Arbitrator and Mediator Panel I: A view from the bench Panelists: • Hon. Cynthia M. Rufe, U.S. District Judge • Hon. Shira Scheindlin, U.S. District Judge (ret.) and AAA Arbitrator and Mediator 2:00 – 2:45 p.m. Moderator: • Roberta Liebenberg, Senior Partner, Fine, Kaplan and Black; and co-author of the ABA report “First chairs at trial: More women need seats at the table” Light refreshments will be served between panel I and panel II Panel II: The in-house counsel perspective Panelists: • Lynn Charytan, EVP and GC at Comcast Cable, and SVP and Senior Deputy GC at Comcast Corporation • Jennifer Dubas, SVP and Chief Compliance Officer at Endo Pharmaceuticals 3:00 – 3:45 p.m. • Malini Moorthy, Head of Global Litigation, VP and Associate GC at Bayer Corporation • PD Villarreal, SVP – Global Litigation at GlaxoSmithKline Moderator: • Sara Begley, Partner, Global Chair – Women’s Initiative Network, Reed Smith 4:00 – 5:00 p.m. Cocktail reception Women in the Courtroom Symposium: Judges, in-house counsel and law firms as change agents Reed Smith 01 Speaker biographies Hon. -

NOTICE of CLE PROGRAM the NDNY-FCBA's CLE Committee

Federal I NDNY FEDERAL COURT BAR ASSOCIATION, INC. www.ndnyfcba.org NOTICE OF CLE PROGRAM The NDNY-FCBA’s CLE Committee Presents “The Time is Now – A Discussion of Achieving Equality in the Courtroom” Thursday, December 3, 2020 3:00 p.m. to 4:15 p.m. RSVP by Monday, November 30, 2020 Because of COVID-19 related restrictions, this CLE will be offered in a virtual setting, via Zoom. To register for this CLE webinar, click the link provided to receive a link to log in. The program will review the Report of the New York State Bar Association Commercial and Federal Litigation Section entitled The Time is Now: Achieving Equality for Women Attorneys in the Courtroom and in ADR, 2020 Women’s Initiative Task Force Follow-Up Study. The presentation will include how the results of the 2019 study differed from those reflected in the Women’s Initiative Task Force Report in 2017. The panel discussion will provide perspective on the reports from members of the judiciary and practitioners and will explore how opportunities for achieving equality can be maximized. Presenters: Hon. Brenda K. Sannes, United States District Judge for the Northern District of New York Hon. Mae D’Agostino, United States District Judge for the Northern District of New York Hon. Shira Scheindlin, United States District Judge for the Southern District of New York (Ret.) Suzanne O. Galbato, Esq., General Counsel, Bond Schoeneck and King, PLLC TIMED AGENDA: 3:00 p.m. - 3:03 p.m. Welcome remarks (Suzanne Galbato) 3:03 p.m. - 3:25 p.m. -

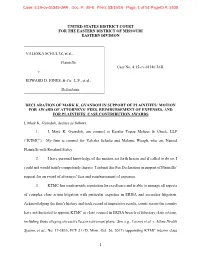

Declaration of Mark Gyandoh in Support of Motion for Attorney's Fees

Case: 4:16-cv-01346-JAR Doc. #: 99-6 Filed: 03/19/19 Page: 1 of 51 PageID #: 2400 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSOURI EASTERN DIVISION VALESKA SCHULTZ, et al., Plaintiffs, Case No. 4:15-cv-01346 JAR v. EDWARD D. JONES, & Co., L.P., et al., Defendants. DECLARATION OF MARK K. GYANDOH IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR AWARD OF ATTORNEYS’ FEES, REIMBURSEMENT OF EXPENSES, AND FOR PLAINTIFFS’ CASE CONTRIBUTION AWARDS I, Mark K. Gyandoh, declare as follows: 1. I, Mark K. Gyandoh, am counsel at Kessler Topaz Meltzer & Check, LLP (“KTMC”). My firm is counsel for Valeska Schultz and Melanie Waugh, who are Named Plaintiffs with Rosalind Staley. 2. I have personal knowledge of the matters set forth herein and if called to do so, I could and would testify competently thereto. I submit this Fee Declaration in support of Plaintiffs’ request for an award of attorneys’ fees and reimbursement of expenses. 3. KTMC has a nationwide reputation for excellence and is able to manage all aspects of complex class action litigation with particular expertise in ERISA and securities litigation. Acknowledging the firm’s history and track record of impressive results, courts across the country have not hesitated to appoint KTMC as class counsel in ERISA breach of fiduciary class actions, including those alleging excessive fees in retirement plans. See, e.g., Larson et al. v. Allina Health System, et al., No. 17-3835, ECF 21 (D. Minn. Oct. 26, 2017) (appointing KTMC interim class 1 Case: 4:16-cv-01346-JAR Doc. -

Request for Leave to File Motion to Address Order of Disqualification

Case: 13-3088 Document: 261-1 Page: 1 11/08/2013 1088212 16 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT Thurgood Marshall U.S. Courthouse 40 Foley Square, New York, NY 10007 Telephone: 212-857-8500 MOTION INFORMATION STATEMENT Docket Number(s): 13-3123 ( corrected ) ; 13-3088 Caption [use short title] Motion for: Leave to A pp ear re: Order of Removal In re Order of Removal of District Judge Set forth below precise, complete statement of relief sought: Undersigned seeks leave to appear on behalf of Hon. Shira A. Scheindlin to address le g al and factual issues raised by the Motion Panel's order of removal dated Oct. 31, 2013. MOVING PARTY: Hon. Shira A. Scheindlin OPPOSING PARTY: N/A 9 Plaintiff 9 Defendant 9 Appellant/Petitioner 9 Appellee/Respondent MOVING ATTORNEY: B ur tN eu b orne OPPOSING ATTORNEY: N/A [name of attorney, with firm, address, phone number and e-mail] 40 Washin g ton S q uare South New York , New York 10012 (212) 998-6172 burt.neuborne @ n y u.edu Court-Judge/Agency appealed from: Motion Panel ( Hons. John M. Walker; Jose Cabranes; Barrin g ton D. Parker, Jr. ) Please check appropriate boxes: FOR EMERGENCY MOTIONS, MOTIONS FOR STAYS AND INJUNCTIONS PENDING APPEAL: Has movant notified opposing counsel (required by Local Rule 27.1): Has request for relief been made below? 9 Yes 9 No ✔9 Yes 9 No (explain): Has this relief been previously sought in this Court? 9 Yes 9 No Requested return date and explanation of emergency: Opposing counsel’s position on motion: 9 Unopposed ✔9 Opposed 9 Don’t Know Does opposing counsel intend to file a response: 9 Yes 9 No ✔9 Don’t Know Is oral argument on motion requested? ✔9 Yes 9 No (requests for oral argument will not necessarily be granted) Has argument date of appeal been set? 9 Yes ✔9 No If yes, enter date:__________________________________________________________ Signature of Moving Attorney: ___________________________________Burt Neuborne Date: ___________________11/8/2013 Service by: ✔9 CM/ECF 9 Other [Attach proof of service] ORDER IT IS HEREBY ORDERED THAT the motion is GRANTED DENIED.